Explore Arizona’s abandoned rail shantytowns safely with these essential tips. Prepare by researching historical sites and obtaining permits. Equip with sturdy boots, water, and a first aid kit. Respect the heritage by preserving artifacts and structures. Leave no trace, take only photos. Plan strategically for an ideal visit. Discover Arizona’s rich railroad history firsthand.

Key Points

- Prioritize safety by obtaining necessary permits and gear.

- Equip with sturdy boots, water, and first aid supplies.

- Respect the historical significance and preserve artifacts.

- Practice minimal impact techniques and leave no trace.

- Plan strategically, research locations, and visit during cooler months.

Research the History and Locations

To fully grasp the significance of Arizona’s abandoned rail shantytowns, explore the intricate history and pinpoint their locations across the vast landscape. These forgotten remnants hold a deep-rooted importance in Arizona’s past, providing a peek into the state’s rich railroad history. By diving into the history of these shantytowns, you can unveil the tales of the individuals who once resided in them, creating a vibrant picture of life during the peak of the railroad era.

As you set out on your journey to discover these hidden treasures, research plays a vital role in understanding their importance. Revealing the stories behind these deserted settlements not only enhances your exploration but also enables you to value the historical significance they possess. By immersing yourself in the history of these shantytowns, you can truly grasp the influence they had on shaping Arizona’s past.

Through diligent investigation and a thirst for knowledge, you can unravel the mysteries of Arizona’s deserted rail shantytowns, transforming your adventure into a meaningful exploration of the state’s history.

Prepare for Rugged Terrain Exploration

Prepare yourself for the rugged terrain exploration ahead by equipping with sturdy boots and ample water supplies to navigate the challenging landscapes effectively. When venturing into Arizona’s abandoned rail shantytowns, trail navigation skills are crucial due to the rough and uneven terrains you’ll encounter. Opt for boots with outstanding ankle support to help you traverse rocky paths and sandy stretches comfortably. Remember to pack enough water to stay hydrated throughout your journey, as Arizona’s arid climate can quickly lead to dehydration.

As you explore these remote areas, be mindful of potential wildlife encounters. Arizona is home to a diverse range of animals, including snakes, scorpions, and various desert creatures. Stay alert and respect their habitats to secure a safe and harmonious coexistence during your expedition. Carrying a basic first aid kit can also prove invaluable in case of any unexpected injuries while traversing the rugged terrain.

Consider Safety and Permits

Before beginning on your exploration of Arizona’s abandoned rail shantytowns, remember to prioritize safety by ensuring you have the necessary gear.

Familiarize yourself with the permit application process to access these sites legally, and be aware of any potential legal implications.

Stay informed and prepared to make the most of your adventure while respecting the rules and regulations in place.

Safety Gear Requirements

When investigating Arizona’s deserted rail shantytowns, make sure you have the necessary safety gear as specified by permits and regulations to safeguard yourself in these distinctive environments.

Safety precautions are crucial, including sturdy hiking boots to protect your feet from rough terrain and potential hazards. Equip yourself with a first aid kit, plenty of water, and a flashlight for emergency preparedness.

Additionally, wearing long pants, gloves, and a hat can shield you from sharp objects and the desert sun. Stay alert and maintain awareness of your surroundings at all times.

Being properly outfitted with the right equipment guarantees you can explore these abandoned sites safely and responsibly, respecting both the environment and your own well-being.

Permit Application Process

Applying for a permit to explore Arizona’s abandoned rail shantytowns is an important step to guarantee the safety of both yourself and the preservation of these historical sites. Understanding the process is vital to make sure a smooth application.

Contact the relevant authorities, such as the local historical society or land management agencies, to obtain information on permit requirements. Provide detailed information about your visit plans, emphasizing safety measures and respect for the site.

Avoiding delays is key, so submit your application well in advance of your intended exploration date. Be prepared to comply with any additional requests or conditions to secure your permit promptly.

Legal Implications Awareness

To guarantee a smooth and safe exploration of Arizona’s abandoned rail shantytowns, it’s essential to be well-informed about the legal implications regarding safety and permits. Understanding the legal ramifications and trespassing consequences is vital, as entering private property without permission can lead to fines or even criminal charges.

Property ownership plays a significant role in exploring these areas, with liability concerns arising if any accidents or incidents occur during your visit. It’s important to respect the property rights of owners and obtain any necessary permits to make certain a lawful exploration experience.

Bring Plenty of Water and Supplies

Make sure to pack an ample supply of water and essential supplies before embarking on your adventure to explore Arizona’s abandoned rail shantytowns. When venturing into the desert to uncover these historical remnants, staying hydrated is vital due to the arid climate and remote locations. Arizona’s abandoned rail shantytowns often lack basic amenities like running water or stores nearby, making it essential to bring enough water to last your entire trip. Consider carrying a reusable water bottle or a hydration pack to make sure you have access to clean drinking water throughout your exploration.

In addition to water, it’s important to stay prepared with other supplies such as snacks, a first aid kit, sunscreen, a map, and a fully charged phone. These items can help you navigate the rugged terrain and unforeseen circumstances that may arise during your visit. By packing smart and thinking ahead, you can enjoy your journey through Arizona’s abandoned rail shantytowns safely and responsibly.

“The EP&SW was leased by the Southern Pacific in the 1920s, and this route became a second main line (“South Line”) for SP between Tucson and El Paso. (SP’s line between Tucson and El Paso via Lordsburg and Deming, NM is known as the “North Line.”) In its heyday, the South Line line hosted through freights and intercity passenger trains like the Golden State Limited.”

https://www.abandonedrails.com/south-line

Explore With Respect for the Past

When exploring Arizona’s abandoned rail shantytowns, it’s essential to honor their historical significance by recognizing the stories they hold.

As you venture through these sites, remember to preserve artifacts and structures for future generations to appreciate.

Leave no trace behind, ensuring that these remnants of the past remain undisturbed and intact.

Honor Historical Significance

Respecting the historical significance of Arizona’s abandoned rail shantytowns involves acknowledging the stories embedded within the decaying structures. Historical preservation and heritage conservation are essential in maintaining the cultural significance of these sites.

Engaging with the community to understand the past and present connections to these locations fosters a sense of appreciation and responsibility. By honoring the historical importance of these shantytowns, you contribute to preserving a piece of Arizona’s history.

Take time to reflect on the lives that once inhabited these places and the impact they had on shaping the state’s development. Approach these sites with reverence and curiosity, allowing the echoes of the past to guide your exploration and deepen your connection to Arizona’s rich heritage.

Preserve Artifacts and Structures

Safeguarding the artifacts and structures found in Arizona’s abandoned rail shantytowns is vital for maintaining their historical integrity and significance.

- Artifact Preservation: Implement measures to protect relics from deterioration, such as establishing protective barriers or conducting regular maintenance checks.

- Community Engagement: Involve local communities in preservation efforts, fostering a sense of ownership and pride in the shared history of the rail shantytowns.

- Historical Significance: Recognize the importance of these artifacts and structures in understanding the cultural impact of rail transportation on Arizona’s development.

Respecting and preserving these remnants of the past ensures that future generations can continue to appreciate the rich history embedded in Arizona’s abandoned rail shantytowns.

Leave No Trace

To explore Arizona’s abandoned rail shantytowns with respect for the past, it’s essential to tread lightly and leave no trace of your presence. Practicing minimal impact techniques safeguards the preservation of these historical sites for future generations. Adhering to environmental ethics, such as refraining from littering or disturbing the surroundings, is vital.

Avoid taking any artifacts or damaging structures, as this disrupts the integrity of the site. When walking through these areas, stay on designated paths or established walkways to minimize disturbance to the environment. Remember that these shantytowns hold significant historical value, and by leaving no trace, you contribute to the conservation of their heritage.

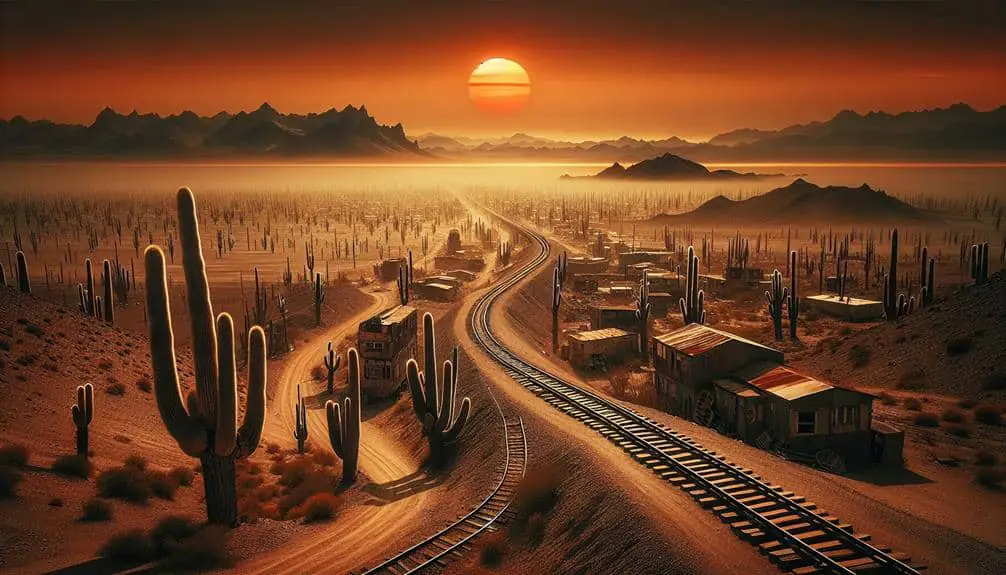

Capture the Beauty Through Photography

Immerse yourself in the haunting allure of Arizona’s abandoned rail shantytowns through the lens of your camera. These desolate landscapes offer a unique opportunity to capture the beauty of decay and the passage of time.

To make the most of your photography experience, consider the following:

- Mastering Lighting Techniques: Play with natural light to create striking contrasts and shadows that enhance the eerie atmosphere of the shantytowns. Early morning or late afternoon light can add depth and dimension to your photographs.

- Perfecting Composition Tips: Experiment with different angles and perspectives to showcase the intricate details of the abandoned structures. Incorporate leading lines or framing techniques to draw the viewer’s eye into the scene.

- Choosing Equipment Essentials and Editing Software Suggestions: Opt for a DSLR or mirrorless camera with a versatile lens selection to capture both wide-angle shots and detailed close-ups. Consider using editing software like Adobe Lightroom or Photoshop to enhance the mood and aesthetic of your photographs.

With these tips in mind, you’ll be ready to capture the haunting beauty of Arizona’s abandoned rail shantytowns with your camera.

Plan Your Visit Strategically

Strategically plan your visit to Arizona’s abandoned rail shantytowns to maximize your exploration experience. To make the most of your trip, consider visiting during strategic timing to avoid extreme weather conditions. The best time to explore these hidden gems is typically during the cooler months, from late fall to early spring, when the temperatures are milder, making your adventure more comfortable and enjoyable.

Research the specific locations you plan to visit beforehand to guarantee you make the most of your time. Some shantytowns may require a bit of hiking or walking to reach, so knowing the terrain and level of difficulty in advance can help you prepare adequately. Additionally, familiarize yourself with any regulations or restrictions in place to respect the historical significance of these sites and preserve them for future visitors.

Frequently Asked Questions

Are There Any Specific Regulations or Guidelines in Place for Exploring Abandoned Rail Shantytowns in Arizona?

When exploring abandoned rail shantytowns in Arizona, remember safety precautions are crucial. These areas hold historical significance but also have legal implications and environmental impacts. Always respect the surroundings, stay informed, and take necessary precautions.

What Are Some Lesser-Known Shantytowns That Are off the Beaten Path and Worth Exploring?

For those seeking hidden gems in Arizona’s abandoned rail shantytowns, consider exploring remote locations like Ruby, Gleeson, and Courtland. These lesser-known sites offer a glimpse into the past and a sense of discovery.

Are There Any Notable Ghost Stories or Urban Legends Associated With the Abandoned Rail Shantytowns in Arizona?

You’ll uncover haunting tales and mysterious sightings linked to Arizona’s abandoned rail shantytowns. Folklore weaves stories of spooky encounters with spirits of the past, adding an eerie allure to these forgotten places.

Are There Any Local Tour Guides or Experts Who Offer Guided Tours of These Shantytowns?

Local experts passionate about historical significance offer guided tours of these shantytowns in Arizona. They share preservation efforts and insights, enriching your exploration with valuable knowledge and a deeper connection to the past.

How Can One Contribute to the Preservation and Conservation of These Historic Sites While Exploring Them?

To help preserve and conserve these historic sites while exploring, you can participate in organized clean-up events, donate to local preservation groups, and educate others about the importance of these shantytowns. Your contribution matters.