You’ll find Allen, Arizona’s ghost town roots in John Brackett Allen’s 1880s settlement near the Ben Nevis Mountains. Originally thriving as a hospitality hub, Allen boasted a luxurious hotel and fine dining establishment that drew travelers and entrepreneurs alike. While the town peaked at 180 residents by 1890, it couldn’t sustain its population, becoming deserted by 1886. The site’s remote location and weathered remains hold fascinating stories of Mormon influence and frontier entrepreneurship.

Key Takeaways

- Allen was established in 1857 by John Brackett Allen, who transformed it from a gold prospecting site into a thriving hospitality-centered settlement.

- The town’s centerpiece was a luxurious hotel built in 1880, serving as both a fine dining establishment and social hub near Quijotoa.

- The settlement peaked at 180 residents in 1890 but became a ghost town by 1886 after significant population decline.

- Unlike typical mining ghost towns, Allen’s legacy centered on hospitality and community services rather than mineral extraction.

- Physical remnants of Allen face preservation challenges due to remote location, weathering, and limited historical documentation.

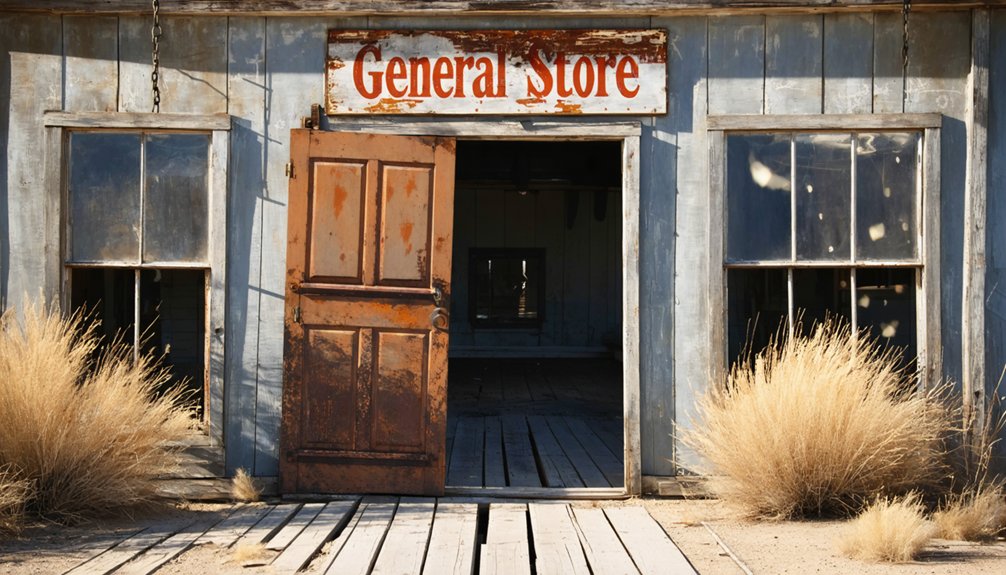

The Founding Legacy of General John Brackett Allen

While gold fever drew countless prospectors to the Arizona Territory in the 1850s, John Brackett “Pie” Allen’s path to prominence began when he arrived in Yuma in 1857. When his gold prospecting failed, he didn’t give up – instead, he launched a successful pie-making venture that funded his future enterprises.

Allen’s entrepreneurship soon expanded to include a major ranch at Maricopa Wells, a thriving store in Tombstone, and numerous development projects throughout the region. He earned his nickname by baking dried apple pies for settlers and soldiers in the area. He received a special tombstone as a gift shortly before his death in 1899.

His political contributions proved equally significant, as he served three terms in the Territorial Legislature and six years as Territorial Treasurer. You’ll find his influence preserved in Tombstone’s Allen Street and his Victorian-era buildings.

As both Tucson’s mayor and the territory’s Adjutant General, “General Pie” helped shape Arizona’s evolution from frontier to civilization.

A Social Hub in Territorial Arizona

As travelers ventured through Arizona Territory in the 1880s, Allen emerged as a vibrant social nucleus near the Ben Nevis Mountains, roughly 50 miles southeast of Ajo.

You’d find the town’s heart in its luxurious hotel, renowned for serving the finest liquors in the territory and hosting countless community gatherings where stories and business deals flowed freely. Much like Allen’s Coffee Brandy, the hotel’s signature drinks became legendary among territorial residents.

The post office, established in 1880, became a cornerstone of social interactions, connecting Allen’s 180 residents with the outside world. Like many ghost towns in Arizona, the community’s dramatic population decline marked its eventual transformation from bustling settlement to abandoned site.

In frontier towns like Allen, the post office served as more than mail delivery – it was the pulse of community life.

You could spot a mix of permanent homes and temporary tents, reflecting the dynamic blend of settlers and visitors who’d gather at this frontier hub.

Until the post office’s closure in 1886, Allen thrived as an essential stopover where miners, ranchers, and travelers found comfort and connection.

Historic Hotel and Fine Dining Heritage

The heart of Allen’s frontier society revolved around its elegant hotel, founded by John Brackett Allen in 1880. Located six miles from Quijotoa, this distinguished establishment offered you more than just lodging – it provided one of the territory’s finest dining experiences, complete with the region’s most exceptional liquors.

Much like the Copper Queen Hotel which boasted two-foot-thick walls, Allen’s hotel was built to withstand the harsh desert climate.

You’d have found yourself immersed in the authentic culinary traditions of territorial Arizona, where the hotel’s dining room served as both a social hub and business center.

The establishment helped transform Allen from a simple frontier outpost into a thriving settlement of 180 residents by 1890. While the physical structure may be gone today, the hotel’s legacy lives on as a representation of how frontier hospitality shaped Arizona’s territorial development and established standards for fine dining in the American Southwest. Just as in Castle Dome’s Hotel La More, visitors reported mysterious sightings and unexplained phenomena throughout the building’s history.

Physical Remnants and Current State

Today, Castle Dome stands as one of Arizona’s best-preserved ghost towns, featuring over twenty original and meticulously reconstructed buildings beneath the dramatic Castle Dome Peak.

You’ll discover more than sixty renovated structures filled with physical artifacts from the mining era, including authentic tools and personal belongings that bring the town’s rich history to life.

The site’s mining remnants include deep mine shafts and tunnels that showcase the scale of past operations. Notable structures include the blacksmith shop, dress shop, barbershop, saloons, jail, and church, all carefully maintained by private owners. Like many historic sites in Arizona, visitors can enjoy gunfight reenactments that bring the Wild West era to life.

The historic Hotel La More, reportedly haunted by miners’ spirits, still stands alongside the town’s original graveyard, while weathered wood and sun-bleached materials testify to the harsh desert environment. The site is now operated as the Castle Dome Mines Museum, offering visitors a comprehensive look at Arizona’s mining heritage.

Mormon Influence and Cultural Impact

You’ll find strong Mormon influence in Allen’s early development through Joseph City, which began as Allen’s Camp in 1876 under William C. Allen’s leadership and Brigham Young’s broader Arizona colonization initiative.

The settlement operated under the United Order principle, with Mormon pioneers sharing communal property ownership and coordinating their labor in farming, irrigation projects, and community dining halls. Following local practices established at settlements like Sunset Fort, residents gathered for meals in a shared dining area.

While other Mormon settlements in the region failed, Joseph City’s religious cohesion and cooperative structure helped it endure, establishing a lasting Mormon presence in Apache County’s development. Like other Arizona Mormon communities, they maintained a narrative of resilience through persecution while building their settlement.

Mormon Settlement Patterns

During the late 19th century, Mormon settlement patterns in northeastern Arizona emerged as part of a broader Church-directed colonization effort that established nearly 20 farming communities in the region.

You’ll find these settlements were strategically placed in fertile valleys with abundant water sources, reflecting careful planning in Mormon migration strategies. The Church maintained tight economic and administrative control to guarantee sustainable agricultural practices, with land specifically apportioned to farmers by 1883.

This settlement pattern extended beyond Arizona as anti-polygamy legislation pushed Mormon communities to seek refuge.

You’ll see this expansion stretching from Canada to Mexico, creating what became known as the Mormon corridor. Communities emphasized self-sufficiency and cooperation, with prominent families like the Romneys and Udalls leading development in Apache County and the Little Colorado River Valley.

Early Religious Community Structure

While Mormon settlements across Arizona varied in size and composition, Allen’s religious community structure exemplified the church’s vision of communal living through the United Order system.

You’ll find that places like Sunset Fort near Allen demonstrated how families shared property and resources collectively, operating shared kitchens and dining halls that strengthened their religious bonds.

Religious governance shaped every aspect of daily life through formalized committees and leadership structures authorized by the church.

You’d see this influence in the cooperative organization of labor, from dam building to farming, all managed according to religious principles.

The Little Colorado River Mission‘s quarterly conferences served as essential forums where community members could address both spiritual matters and practical concerns, maintaining order through church-directed leadership.

Distinguishing Features From Mining Ghost Towns

Unlike most Arizona ghost towns born from mining rushes, you’ll find Allen’s origins rooted in Mormon settlement patterns that emphasized community and religious values rather than mineral extraction.

You can trace Allen’s distinctive character through its focus on civic infrastructure and agricultural development, which contrasts sharply with the mining camps’ temporary boom-and-bust cycles.

While mining ghost towns typically preserved extensive industrial equipment and saloons, Allen’s legacy centers on more stable settlement features like wooden water tanks and community gathering spaces, reflecting its unique role as a social and religious hub.

Social Hub Origins

As a proof of its unique origins, Allen distinguished itself from Arizona’s typical mining ghost towns through its establishment as a hospitality-focused settlement.

John Brackett Allen’s vision centered on creating a welcoming stopover by building a hotel on the western side of Ben Nevis Mountain, 50 miles southeast of Ajo. Rather than emerging from a mineral strike, the town’s social dynamics revolved around traveler experiences at what became known as the territory’s finest hotel.

You’ll find that Allen’s development wasn’t driven by ore deposits or mining claims, but by Allen’s entrepreneurial spirit to serve settlers heading to Quijotoa.

The hotel became the heart of community life, attracting a steady stream of visitors and fostering a unique frontier atmosphere focused on comfort and hospitality rather than mineral extraction.

Preserved Hotel Legacy

Today’s remaining traces of Allen’s distinguished hotel legacy stand in stark contrast to Arizona’s typical mining ghost towns.

Unlike the industrial remnants you’ll find at sites like Castle Dome or Bisbee, Allen’s heritage centers on its luxury hotel architecture and sophisticated hospitality. The town’s unique character emerged from John Brackett Allen’s vision of creating an upscale desert retreat rather than a rough mining camp.

- Hotel offered the territory’s finest liquors and premium amenities, attracting non-mining travelers

- Settlement layout focused on hospitality infrastructure instead of industrial facilities

- No mining equipment or processing ruins remain, highlighting its service-based economy

- Community’s social fabric revolved around hotel operations rather than mineral extraction

These distinctive features make Allen a rare example of a frontier town built purely for comfort and leisure.

Non-Mining Economic Base

The economic foundation of Allen set it distinctively apart from Arizona’s numerous mining ghost towns. Unlike settlements built around ore extraction, Allen thrived on its hospitality industry, centered primarily on John Brackett Allen’s hotel.

You won’t find mine shafts, processing mills, or tailings here – instead, the town’s economy revolved around serving travelers and miners from the nearby Quijotoa district, located six miles east.

The hotel established itself as a regional social hub, offering quality liquors and comfortable accommodations that stood out on the frontier.

While the transient population of miners and travelers sustained the local economy, Allen never developed the industrial infrastructure typical of mining towns.

You’ll notice the absence of company stores, assay offices, and equipment suppliers that characterized true mining settlements.

Preservation Challenges and Historical Significance

Despite its brief existence in the 1880s, Allen stands as a compelling proof of Arizona’s mining boom-and-bust cycle, facing significant preservation challenges due to its remote desert location and lack of formal protection.

You’ll find that without formal preservation methods in place, the site remains vulnerable to weathering, vandalism, and artifact looting. While the town’s historical education potential is significant, its isolation makes conservation efforts and tourism development particularly challenging.

- Original structures, including the renowned hotel and six houses, have likely deteriorated substantially since abandonment.

- Limited historical documentation hinders public awareness and advocacy efforts.

- No current preservation initiatives protect the site’s remaining foundations and artifacts.

- The ghost town’s authenticity offers unique research opportunities for understanding frontier settlement patterns.

Frequently Asked Questions

What Happened to the Original Hotel’s Furnishings and Valuable Artifacts?

You’ll find no documented furnishings origins or artifact discoveries from Allen Hotel, as they were likely removed by departing residents, scavenged by locals, or left to decay naturally.

Are There Any Surviving Photographs of Allen During Its Peak Period?

Like footprints in the sand, historic imagery of Allen’s peak period hasn’t surfaced. You won’t find any confirmed visual documentation in major archives, though some photographs could exist in private collections.

What Transportation Routes Connected Allen to Other Territorial Settlements?

You’d find railroad connections along Southern Pacific’s mainline and stagecoach routes connecting Allen to Tucson, Tombstone, and Benson, with dirt roads linking nearby mining camps and ranches.

Did Any Notable Historical Figures Frequent the Hotel in Allen?

You won’t find records of famous visitors or hotel legends at Allen’s establishment, despite its reputation for luxury and fine liquors. No documented evidence exists of any notable historical figures staying there.

When Exactly Did the Last Permanent Residents Leave Allen?

Even with today’s GPS tracking, you can’t pinpoint exactly when Allen’s last residents left. Based on regional ghost town patterns, they likely departed between the 1950s and 1970s, leaving only ghost stories behind.

References

- https://www.islands.com/1897773/longest-working-mining-town-arizona-abandoned-mountain-ghost-castle-dome-landing/

- https://www.atlasobscura.com/itineraries/these-8-arizona-ghost-towns-will-transport-you-to-the-wild-west

- https://everafterinthewoods.com/this-arizona-ghost-town-still-draws-visitors-with-its-wild-west-charm/

- https://photos.legendsofamerica.com/blog/2017/2/that-time-when-walking-the-streets-of-tombstone

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_ghost_towns_in_Arizona

- https://southernarizonaguide.com/ghost-towns-southern-arizona/

- https://www.ghosttowns.com/states/az/allen.html

- https://www.worldatlas.com/cities/7-off-the-map-towns-in-arizona.html

- https://bignosekatestombstone.com/history/allen-street-tombstone-arizona/

- https://hoteltombstone.com/tombstone-az-history/