You’ll find Catoctin tucked away in Yavapai County’s copper country, a modest ghost town founded in 1884 by Pennsylvania transplant Frank Alters. This gold and silver mining outpost never housed more than 20 souls during its brief 1884-1920 existence. Today, only weathered ruins, desert-reclaimed foundations, and a small cemetery with 19th-century headstones remain. The dusty trails to this forgotten settlement reveal Arizona’s mining dreams that sparkled briefly before fading into the landscape.

Key Takeaways

- Established in 1884 by prospector Dosoris Cox, Catoctin was named after mountains in Pennsylvania and primarily mined gold and silver.

- The settlement never exceeded 20 residents and operated a post office from 1902 until its closure in 1920.

- Catoctin Mine operated from 1927-1937, employing small workforces and using gravity separation techniques for mineral extraction.

- British investors suffered losses from fraudulent assays, exemplifying the economic challenges typical of boom-bust mining ventures.

- Today, only weathered ruins, reclaimed by native vegetation, remain as modest remnants of this small Arizona mining settlement.

Origins of a Forgotten Mining Outpost

Though time has nearly erased its presence from Arizona’s rugged landscape, Catoctin’s story begins in 1884 with prospector Dosoris Cox‘s fateful discovery. Cox named the site after his boyhood home, staking his claim in the Little Copper Creek District of Yavapai County.

You’ll find Catoctin history interwoven with the Bradshaw Mountains, perched at 5,079 feet where early miners pursued veins of gold and silver, with copper and lead as secondary prizes.

Early mining techniques were rudimentary, yielding modest returns without corporate backing. The settlement remained small but determined, a reflection of frontier resilience. Like many Arizona mining camps, Catoctin experienced a brief boom period followed by inevitable decline.

The establishment of a post office in 1902 marked Catoctin’s official recognition, though the outpost would never grow beyond a remote mining camp serving the hardy souls who ventured into Arizona’s mineral-rich wilderness. The mine later came under the ownership of Catoctin Mining Co. who operated the site as a producer during its active years.

Frank Alters: The Founder and His Pennsylvania Connection

You can still trace Frank Alters’ Pennsylvania influence in the naming of Catoctin, Arizona, as he christened his 1884 discovery after the mountains of his eastern homeland.

His entrepreneurial vision shifted from mining interests with the Aztec Land & Cattle Company to establishing ranching operations near Adamana, where land proved affordable yet accessible.

Similar to how the American Ranch served as a stage stop on the Prescott-Ehrenburg route, Alters brought eastern mining techniques west, though his settlement never flourished beyond twenty residents before the post office closed in 1920, marking the quiet end of his frontier experiment. Like many settlers during this period, Alters and his neighbors relied on the Santa Fe Railroad for transportation and shipping goods.

Pennsylvania Roots Transplanted

When Frank Alters discovered what would become Catoctin in 1884, he carried more than just prospecting tools across the harsh Arizona terrain—he brought the memory of his Pennsylvania hometown.

This transplanting of names wasn’t unusual for the era. You’ll find countless Western settlements christened after Eastern origins, a practice that helped pioneers maintain threads of familiarity in unfamiliar lands. Alters’ decision to stamp his Pennsylvania heritage onto Arizona soil followed a well-worn path of settler traditions.

The migration westward saw numerous Pennsylvanians seeking opportunity and open spaces, bringing cultural touchstones with them. Alters’ naming choice serves as a subtle reminder of how the West was shaped by Eastern influence.

Today, Catoctin’s name stands as silent testimony to the personal histories that built Arizona—each town a mosaic of memories carried across a continent.

Alters’ Entrepreneurial Vision

Frank Alters didn’t simply discover Catoctin—he envisioned transforming the rugged Yavapai County landscape into a thriving community that mirrored his Pennsylvania roots.

When you stand where Alters once stood in 1884, you’ll recognize his strategic settlement strategy: the castle-like geographic features, life-giving water sources, and mining potential all promised prosperity.

As deputy sheriff, Alters wielded influence beyond founding the town, using his Eastern industrial knowledge to tackle entrepreneurial challenges in this frontier outpost.

Despite his ambitions, Catoctin never flourished—by 1914, only 20 hardy souls called it home. The post office operated for just eighteen years before surrendering to the desert’s harsh realities.

His vision ultimately faded, but Alters’ determination embodied the pioneering spirit that drew so many eastward, seeking freedom in Arizona’s open landscapes.

East Coast Mining Influence

The Pennsylvanian roots of Catoctin’s origin story run deeper than mere coincidence or convenience. When Frank Alters claimed this dusty corner of Arizona in 1884, he carried with him more than prospecting tools—he brought an Eastern Influence that shaped the settlement’s very identity.

By naming his discovery after his Pennsylvania homeland, Alters etched his origins into the desert landscape.

You’ll find the intersection of two mining worlds here: Pennsylvania’s coal and iron traditions meeting Arizona’s precious metal frontier.

While records don’t specify which Mining Techniques Alters transported westward, his journey mirrors countless eastern entrepreneurs who sought freedom in Arizona’s open territories. Alters’ abandoned mining town eventually became one of many ghost towns that dotted the landscape after the gold rush fervor died down.

The eastern capital networks that eventually consumed nearby operations like Crook City were already forming pathways that would transform how western mines operated—with Catoctin standing as proof of this transcontinental exchange.

Life in Catoctin During Its Brief Existence

Life in Catoctin during its brief existence embodied the harsh realities faced by frontier mining communities throughout Arizona’s rugged terrain. You’d have found yourself among just 20 residents in 1914, sharing the daily struggles of a community that never quite flourished despite early promise.

Social interactions centered around the post office—the community’s lifeline from 1902 until 1920. Without formal schools, churches, or entertainment venues, your connections would’ve been limited to fellow miners and their families. Unlike nearby Ghost Town Trail communities such as Gleeson, Courtland, and Pearce, Catoctin never developed significant infrastructure.

The post office served as Catoctin’s heart, providing rare moments of connection in this isolated mining settlement’s harsh existence.

Living conditions remained rudimentary, with minimal infrastructure and basic accommodations typical of frontier settlements. Much like the Catoctin Furnace area in Frederick County, the region had historical ties to mining operations. You’d have battled the desert environment’s challenges—hot summers and limited water access—while traversing rugged roads requiring four-wheel drive.

The economic opportunities never materialized beyond small-scale mining, ultimately leading to Catoctin’s abandonment when mining ceased to sustain even this tiny population.

The Rise and Fall: Timeline of a Short-Lived Settlement

You’d scarcely believe Catoctin’s entire existence spanned just twenty years, from Frank Alters’ 1884 discovery to the post office’s closure in 1920.

The town’s official establishment in December 1902 marked its formal recognition, though mining activity had already drawn a small population to this remote corner of Yavapai County. Similar to many mining towns in Arizona, Catoctin faced eventual abandonment when its resources were depleted.

Like its namesake in the Mid-Atlantic region, this Arizona settlement borrowed the Algonquian-derived name that has historically designated various geographical features across America.

Founding to Forgotten

Though barely a footnote in Arizona’s mining history, Catoctin emerged from the dusty hills of Yavapai County in 1902, carving out a brief existence along the upper Hassayampa River.

You’d have found just a handful of determined souls there, drawn by Frank Alters’ 1884 gold discovery but facing persistent mining challenges in the rugged terrain.

The settlement’s heartbeat—gold extraction from the Catoctin and Climax mines—never quite flourished as hoped.

With population hovering around 20 hardy souls, the town established its post office in December 1902, only to see it shutter by July 1920.

Mining operations sputtered into the 1930s before economics and isolation prevailed.

Today, you’ll find just one standing structure—silent testimony to frontier ambition transformed into Arizona’s quietest ghost town.

Twenty-Year Wonder

Catoctin’s brief but significant existence spans barely two decades—a mere heartbeat in the timeline of Western settlement.

You’d find the community dynamics revolved entirely around the mining operations that breathed life into this dusty outpost.

The settlement’s timeline unfolds in stark desert clarity:

- 1902: Camp establishment and post office opening, marking Catoctin’s official birth

- 1914: Population peaks at merely 20 souls, their fortunes tied to primitive mining technology

- 1920: Post office closure signals the community’s formal death

- 1927-1937: Final gasps of mining activity before silence claims the land

While never achieving boomtown status, Catoctin represents the fierce independence and determination of those who carved possibilities from Arizona’s unforgiving landscape, however fleeting their mark.

What Remains: Traces of Catoctin Today

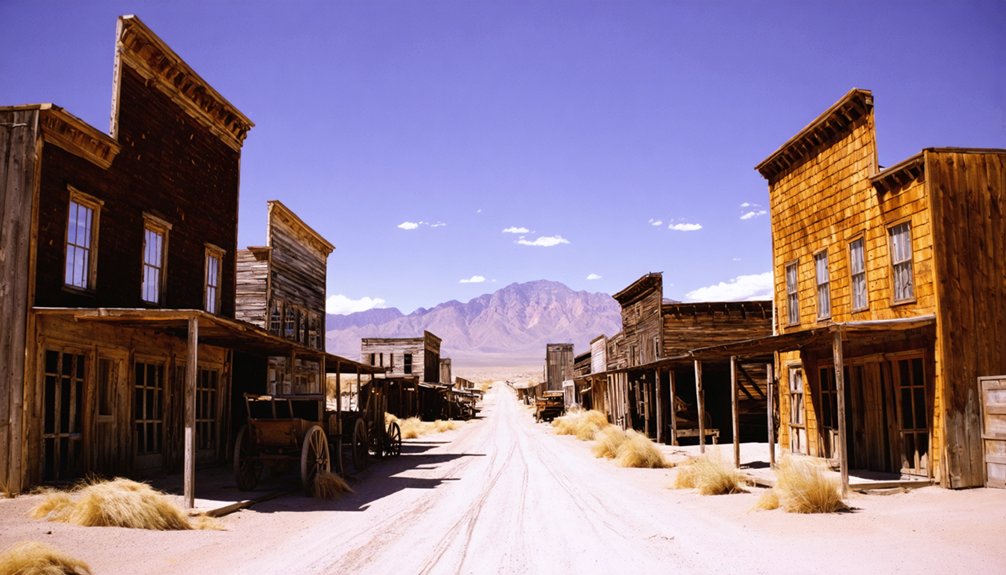

The weathered remains of Catoctin stand as silent sentinels against Arizona’s relentless desert time.

You’ll find skeletal buildings—roofless and hollowed—scattered across the landscape where miners once sought fortune. The Bradshaw Mountains have reclaimed much of what man built, with native vegetation slowly consuming foundation stones and structural remnants. Like many settlements abandoned during the Great Depression, Catoctin fell victim to economic hardship when mining operations became unsustainable.

The Catoctin ruins tell stories without words, while the nearby cemetery offers tangible connections to those who lived and died during the settlement’s brief heyday.

Weathered tombstones from the late 1800s provide names and dates—sometimes the only remaining record of a soul’s passage through this harsh terrain.

Access requires determination; rugged roads lead adventurous spirits to this forgotten corner where wildlife now rules what humans abandoned, and mine shafts wait as dangerous reminders of bygone ambitions.

Mining Operations and Economic Activities

Behind the weathered ruins that dot today’s landscape once pulsed the lifeblood of Catoctin—its mining operations. The Catoctin Mine extracted gold and silver from 1927 to 1937, employing underground techniques to follow rich veins beneath the Arizona soil at 5,079 feet elevation.

The mine’s economic impact rippled through the region:

- Small workforces managed intensive extraction, with nearby dredging operations run by just five determined men.

- British investors poured capital into these hills, often losing fortunes to fraudulent assays.

- Gravity separation and amalgamation mining techniques defined Catoctin’s operations.

- Economic fluctuations followed the boom-bust cycle typical of frontier enterprises.

You’ll find evidence of both success and struggle in this ghost town—where freedom-seeking pioneers gambled everything on the golden promise hidden in Yavapai County’s rugged terrain.

Catoctin’s Place Among Arizona Ghost Towns

Among the countless ghost towns scattered across Arizona’s sunbaked landscape, Catoctin stands as a particularly humble footnote in the state’s mining history.

Unlike the more prominent ruins of Goldfield or Ruby, which boasted thousands of residents and bustling commercial districts, Catoctin’s significance lies in its representation of the smallest scale mining ventures.

While grand ghost towns tell of booming frontier wealth, Catoctin whispers the quieter story of modest mining dreams.

You’ll find Catoctin’s story remarkably brief compared to other ghost town legends. With barely 20 souls at its peak and a post office that operated just 18 years (1902-1920), it never developed beyond a modest cluster of structures.

In ghost town comparisons, Catoctin exemplifies the ephemeral nature of frontier speculation—where dreams of gold yielded only fleeting settlements rather than enduring communities.

Its minimal preservation status today further reflects its minor role in Arizona’s rich tapestry of abandoned mining camps.

Visiting the Former Site: What to Expect

When approaching Catoctin today, you’ll find yourself traversing rugged Yavapai County backcountry that demands respect and preparation.

This forgotten gold mining outpost stands as a symbol of Arizona’s boom-and-bust frontier spirit, with just one solitary structure defying time’s relentless march.

For safe, rewarding exploration, heed these site safety fundamentals:

- Navigate via GPS coordinates (34°25′32″N 112°31′50″W), as no signage marks this ghost settlement.

- Bring ample water and supplies—you’re on your own in this untamed terrain.

- Wear sturdy boots for uneven ground and watch for hazards around mining remnants.

- Plan your visit during spring or fall when desert conditions prove most forgiving.

Your 4WD vehicle is non-negotiable; freedom in these parts comes with self-reliance.

Frequently Asked Questions

Did Any Famous Figures or Outlaws Visit Catoctin?

No, you won’t find famous visitors or outlaw legends in Catoctin’s dusty past. Unlike Castle Hot Springs nearby, this small mining outpost didn’t attract frontier celebrities or notorious gunslingers.

Were There Any Major Disasters or Notable Deaths in Catoctin?

Like footprints washed away by desert rain, Catoctin’s history reveals no major disasters or notable deaths. You’ll find its dust carries only whispers of quiet decline, not tragedy’s heavy burden.

Did Indigenous Peoples Have Settlements Near Catoctin Before Mining Began?

You’ll find indigenous settlements were limited to seasonal camps near Catoctin. Native peoples quarried rhyolite for tools, giving the area cultural significance, but established no permanent villages before miners staked their claims.

What Happened to Catoctin’s Residents After the Town Declined?

You’d trace Catoctin migration patterns to neighboring mining camps when gold depleted. Catoctin resident stories reveal they scattered like desert seeds, seeking fortune elsewhere—their pioneer spirits refusing confinement to dying prospects.

Are There Any Photographs of Catoctin During Its Active Years?

Like lost nuggets in desert sand, Catoctin’s history remains visually elusive. You won’t find mining photographs from its active years—this frontier outpost’s fleeting existence escaped the photographer’s discerning eye.

References

- https://azgw.org/yavapai/ghosttowns.html

- https://www.arizonahighways.com/ghost-town-trail

- https://kids.kiddle.co/List_of_ghost_towns_in_Arizona

- https://www.islands.com/1740327/get-away-from-all-strange-arizona-ghost-town-famed-unusual-name-nothing/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_ghost_towns_in_Arizona

- https://www.ghosttowns.com/states/az/catoctin.html

- https://janmackellcollins.wordpress.com/2020/04/15/whats-in-a-name-yavapai-county-arizona-ghost-towns-vary-from-whimsical-to-wondrous/

- http://www.azarchivesonline.org/xtf/view?docId=ead/uoa/UAMS562.xml;query=mesa;brand=default;hit.rank=1

- https://goldfieldghosttown.com

- https://westernmininghistory.com/mine-detail/10048230/