Sasco, Arizona, established in 1906 by the Development Company of America, once thrived as a mining company town with a population of 600. You’ll find it centered around a massive smelter that processed ore from nearby Silverbell mines until 1921. The town quickly declined after bankruptcy, Spanish flu, and violence at Wilson’s Saloon. Today, you can explore haunting ruins including the smelter stack, Hotel Rockland, and Sasco Cemetery that tell a forgotten chapter of Arizona’s mining history.

Key Takeaways

- Sasco was a mining company town established in 1906 that processed ore from nearby Silverbell Mine until 1921.

- The town’s economy centered around its massive smelter, which processed over 240,000 tons of ore during peak operations.

- At its height, Sasco had approximately 600 residents with amenities including a hotel, post office, jail, and saloons.

- Spanish flu, economic collapse, and violent incidents contributed to Sasco’s abandonment by the early 1920s.

- Today, Sasco’s ruins include a prominent smelter stack, Hotel Rockland remains, jail building, and a cemetery with pandemic victims.

The Birth of a Company Town

While many Arizona ghost towns began as spontaneous mining settlements, Sasco emerged with deliberate corporate planning on August 10, 1906. The Development Company of America (DCA), led by Frank M. Murphy, established this carefully designed community with a clear company vision: consolidate mining, railroad, and processing operations under one entity.

You’ll find Sasco’s origins firmly rooted in industrial strategy. After acquiring the Union and Mammoth mines in 1903, Murphy and chief engineer William Field Staunton needed a processing hub.

They constructed the Arizona Southern Railroad in 1904, connecting the Silverbell Mine to the Southern Pacific line at Red Rock. This infrastructure laid the foundation for community spirit as the town grew to support the smelter, which began construction in 1907 and would employ 175 men. The smelter was officially completed in February 1908 and quickly became the economic center of the burgeoning town. The name “Sasco” itself was derived from the Southern Arizona Smelting Company, reflecting its primary industrial purpose.

Rise and Fall of the Southern Arizona Smelting Company

You’ll witness Southern Arizona Smelting Company‘s impressive but brief arc through Arizona’s industrial landscape from 1906 to 1921.

The smelter processed over 240,000 tons of ore during its operation, surviving a bankruptcy (1909-1911) only to be revitalized through ASARCO’s 1915 acquisition before finally succumbing to the dual pressures of financial troubles and the Spanish flu pandemic. The smelting town followed a similar development pattern to other company towns like Hayden, which was founded in 1909 as a base for ASARCO’s expanding mining operations. The transition from underground mining to open-pit methods in the 1930s came too late to save Sasco’s operations.

This economic rollercoaster transformed Sasco from a promising industrial hub with 600 workers at its peak into an abandoned ghost town, leaving behind only ruins and a cemetery filled with pandemic victims.

Corporate Boom and Bust

As the twentieth century’s first decade unfolded, the Southern Arizona Smelting Company emerged as a textbook example of mining boom-and-bust economics. The corporate ethics of the era embraced rapid expansion with little concern for sustainability.

You’ll find the company’s aggressive trajectory impressive—after founding in 1906, they built an entire town by early 1908, processed over 240,000 tons of ore by 1910, and employed 175 men during peak operations.

The mining industry’s volatile nature soon revealed itself when financial troubles struck in 1911, forcing founder Murphy into bankruptcy.

Despite ASARCO’s revival attempt in 1915, the Spanish Flu devastated the workforce, and Silverbell Mine’s 1921 closure delivered the fatal blow. The population, which once reached 600 residents, declined rapidly after the smelter’s closure. Today, visitors can explore the haunting smelter complex remains as testament to this once-thriving industrial center.

Ore Processing Operations

The Southern Arizona Smelting Company‘s ambitious ore processing operations defined Sasco’s brief but intense industrial life. Construction of the smelter complex began in summer 1907 and was completed by February 1908, quickly establishing a significant industrial footprint in southern Arizona.

At its peak, the facility employed 175 men who processed an impressive 245,000 tons of copper ore by 1910. The operation utilized traditional smelting techniques, using furnaces to separate copper from waste materials and create slag. This contrasted with modern leaching methods that would later dominate the industry.

The smelter processed complex ore types containing copper with associated gold, silver, lead, molybdenum, and vanadium. Despite its technological capabilities, the operation faced financial troubles when bankruptcy forced closure between 1909 and 1911, ultimately ending Sasco’s promising industrial era.

Financial Takeover Timeline

Founded on August 10, 1906, Southern Arizona Smelting Company (SASCO) emerged from Frank M. Murphy’s vision to consolidate mining operations and transportation networks in the Silver Bell Mountains.

Despite ambitious beginnings, financial struggles delayed smelter construction until 1907, with completion in February 1908.

By 1911, Murphy’s bankruptcy forced SASCO’s shutdown after processing 240,000 tons of ore. The company’s collapse devastated the town’s economy and population.

In 1915, corporate consolidation brought new life when ASARCO purchased the Silverbell Mine and SASCO facilities. Operations resumed briefly with 175 workers supporting a population of approximately 600 residents.

This revival proved short-lived. The Spanish flu pandemic of 1918 decimated the workforce, and persistent unprofitability sealed SASCO’s fate, marking the final chapter for this ambitious mining enterprise.

Life in Sasco During Its Prime

When Sasco reached its peak in the early 1910s, roughly 600 residents called this copper smelting town their home.

You’d find them working in shifts at the smelter that processed an impressive 245,000 tons of copper ore by 1910. The community dynamics revolved around the Southern Arizona Smelting Company, which built and maintained most infrastructure.

Daily routines centered on industrial labor for the 175 employed men, while families occupied company housing nearby. The town thrived due to mining development similar to other Arizona ghost towns of the era.

After long shifts, workers might visit one of the town’s saloons, stores, or gather at “the big house” – an unofficial social center built by the smelter overseer. Surviving through the harsh desert climate where temperatures could reach 122 degrees was a constant challenge for residents.

The post office, active from 1907 to 1919, connected residents to the outside world, while the Hotel Rockland served both travelers and locals.

Tragedy, Crime, and Abandonment

During the winter of 1918-1919, you’d have witnessed the Spanish Flu devastate Sasco’s population, leaving behind rows of simple concrete headstones in the town cemetery as grim evidence.

Just as the pandemic was waning in April 1919, you’d have heard about the shocking incident at Wilson’s saloon, where the owner fatally shot Charlie Coleman who’d arrived from Bisbee seeking violent revenge against two men involved with his wife.

These tragedies occurred during Sasco’s final days as a functioning community, with the post office closing later that same year and marking the beginning of the town’s formal abandonment.

The town once thrived with approximately 600 residents at its peak, supporting facilities including a hotel, post office, and jail before its decline.

Spanish Flu Devastation

As America battled the worldwide Spanish Flu pandemic of 1918-1920, Sasco endured its own devastating chapter in this global tragedy. While specific records of Sasco’s experience remain limited in historical archives, we can understand its likely impact through the documented devastation in nearby Arizona mining communities.

- Mining towns like Sasco were particularly vulnerable to rapid disease spread due to crowded working conditions, communal housing, and limited medical facilities typical of early 20th-century industrial settlements.

- The pandemic likely accelerated Sasco’s decline as the combination of illness, mining industry challenges, and population loss created compounding hardships. Similar to Bisbee, Arizona, which saw around 160 deaths by the end of 1918, Sasco likely experienced proportional losses that devastated families and weakened the community’s resilience.

- This health crisis represents an important yet often overlooked aspect of Sasco history, as pandemic impacts frequently remain overshadowed by economic narratives in ghost town chronicles.

Murder at Wilson’s

The decaying remains of Sasco harbor a dark chapter of violence that occurred at Wilson’s Saloon in the early 1920s, shortly before the town’s final collapse.

As miners departed and businesses failed, social tensions escalated, culminating in a family tragedy that shocked the remaining inhabitants.

You can still see the crumbling foundation where Wilson’s once stood—a site that echoes the rural violence that plagued dying mining communities.

The murder allegedly involved a dispute between relatives, with four family members killed in a single night of bloodshed.

The incident accelerated Sasco’s abandonment, as remaining residents fled what they now considered cursed ground.

This dark episode represents the social disintegration that often accompanied economic collapse in Arizona’s ghost towns.

What Remains: Exploring Sasco’s Ruins Today

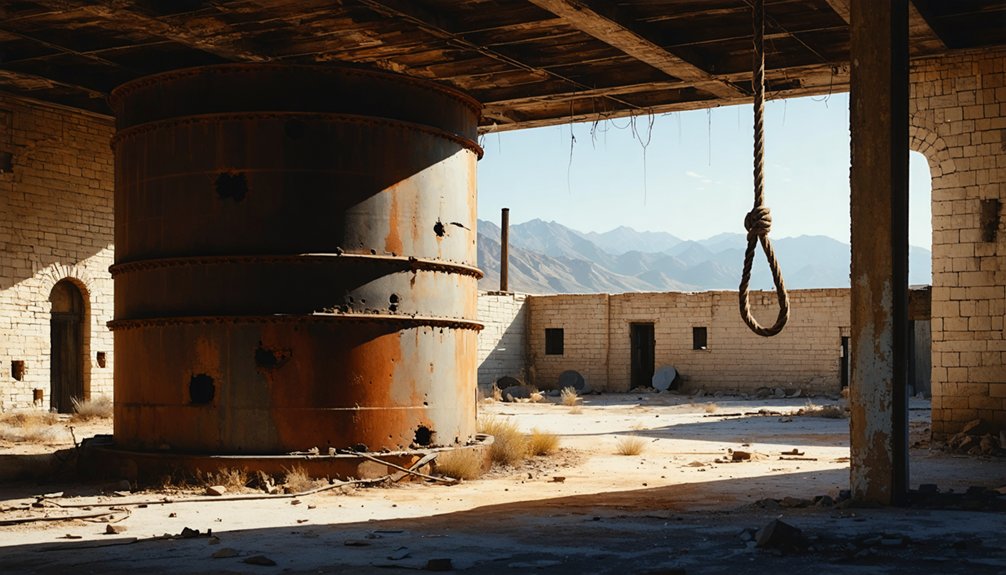

Visitors to Sasco today encounter a haunting collection of ruins that tell the story of this once-thriving mining community. The massive smelter stack dominates the landscape as the most prominent feature, surrounded by scattered foundations of the stamp mill and railroad platforms that once supported the town’s industrial heart.

Haunting ruins whisper Sasco’s bygone glory, the towering smelter stack standing sentinel over industrial ghosts.

You’ll find three notable structures still standing:

- The volcanic stone Hotel Rockland near Sasco Road

- The jail building, representing law enforcement in this frontier town

- The Sasco Cemetery northeast of the site, with plain concrete crosses marking flu pandemic victims

Unfortunately, decades of neglect have taken their toll. Ruins photography enthusiasts document these fragments of history, though graffiti and trash threaten historical preservation efforts.

The desert reclaims these remnants gradually, erasing what civilization briefly established.

Visiting the Ghost Town: Access and Preservation

Planning a journey to Sasco requires careful preparation due to the ghost town‘s remote location and challenging terrain. You’ll find the most direct access route via I-10’s Red Rock exit (226), where Sasco Road begins. The road remains paved for about 4 miles before shifting to dirt, demanding high-clearance vehicles beyond this point.

When exploring, adhere to visitor guidelines that protect this fragile historical site. The ghost town isn’t officially preserved, leaving structures vulnerable to vandalism and decay.

Practice Leave No Trace principles, avoid removing artifacts, and stay on designated trails. Winter offers the most favorable conditions, while monsoon season (July-September) can render access routes impassable due to flooding at the Santa Cruz River crossing.

Always carry emergency supplies, as services are nonexistent in this remote area.

Frequently Asked Questions

Who Were the Prominent Residents Besides Mead Goodloe?

James Murphy established the Southern Arizona Smelting Company in 1906. Prominent families included Wilson, the saloon owner, while railroad workers and mining officials from Asarco held historical significance after 1915.

Are There Any Ghost Stories or Paranormal Claims About Sasco?

Strange as it may seem, there’s a notable absence of documented ghost sightings at Sasco. You won’t find credible paranormal investigations or haunting claims in any reputable sources about this abandoned town.

What Was Daily Wage for Smelter Workers in Sasco?

You’d have earned between $2-$5 daily at Sasco’s smelter in the early 1900s. Worker conditions were harsh, featuring 10-hour shifts and varying wages based on your skill level and economic cycles.

Where Did Sasco Residents Get Their Water Supply?

Parched like the desert itself, you’d rely on water sources delivered by Arizona Southern Railroad tank cars. Supply methods included storage in tanks near the company store with rationed access two hours each morning.

Were Any Movies or Media Productions Filmed at Sasco Ruins?

You won’t find major film productions at Sasco ruins. Available research shows no documented media representations beyond exploratory YouTube videos, with recreational paintball activities now dominating the site rather than cinematic endeavors.

References

- http://www.ghosttownaz.info/sasco-smelting-ghost-town-ruins.php

- https://azoffroad.net/sasco

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sasco

- https://www.boldcanyonoutdoors.com/2020/05/28/exploring-ironwood-national-monument-sasco-the-silver-bell-cemetary/

- https://kids.kiddle.co/Sasco

- https://www.youtube.com/shorts/wzkwx54VqpA

- https://hikearizona.com/decoder.php?ZTN=984

- https://www.theirminesourstories.org/post/asarco-grupo-mexico-chronology

- https://winfirst.wixsite.com/arizonamininghistory/history

- https://www.ghosttowns.com/states/az/sasco.html