Elna (now Helena) began as a lawless mining camp in 1851 near a former Native American settlement. You’ll find this Trinity County ghost town 1/4 mile off Highway 299 via East Fork Road. The site peaked around 1860 with 500 residents before declining when gold deposits were exhausted and Highway 299 bypassed the settlement. Six original structures remain, including the Meckel Store, preserving authentic Gold Rush architecture. The town’s complex naming history holds clues to its colorful past.

Key Takeaways

- Elna was established as a mining camp in 1851 during California’s Gold Rush, later renamed Helena in 1891.

- The town peaked around 1860 with 500 residents before declining when gold deposits were exhausted.

- Six original structures survive, including the Schlomer Brewery and Meckel Store, showcasing Gold Rush-era architecture.

- The ghost town was designated on the National Register of Historic Places in 1984.

- Located near Highway 299, Elna is privately owned with no visitor amenities or interpretive signage.

The Ancient Roots of a Mining Frontier

Long before the gold rush transformed California’s landscape into a patchwork of boomtowns and mining camps, the area that would become Elna hosted a rich tapestry of indigenous life.

Archaeological evidence reveals human presence dating back approximately 4,000 years, with Native Americans establishing ancient settlements throughout the region.

The ancient human tapestry of this land stretches back millennia, with indigenous communities weaving their stories across the landscape.

You’ll find that these original inhabitants developed sophisticated relationships with the land, creating indigenous trails that later influenced the placement of mining camps and supply routes during the 1850s gold rush.

They expertly utilized local rivers and mineral deposits, leaving behind cultural artifacts and landscape modifications that testify to their deep connection to this territory.

Their ancient footprint provided the foundation upon which later European-American mining activities would build, though this connection remains underappreciated in many historical accounts of California’s development.

Tragically, the Native American population drastically declined from 150,000 in the 1840s to just 16,000 by 1880 due to disease, displacement, and violence brought by settlers.

Similar to Helena which was initially named North Fork, this area underwent several name changes as settlements evolved during the mining era.

From North Fork to Bagdad: A Town’s Many Names

You’ll find the evolution of this mining settlement’s identity reflected in its shifting nomenclature, from its practical beginnings as North Fork to its colorful reputation as Bagdad.

The town’s rowdy character during the gold rush era established its reputation as a frontier boomtown with a distinctly untamed atmosphere. The settlement was built on the site of Chimariko Village, which had been a Native American camp before miners arrived. John Carr became the first recorded white settler in the area in 1851, establishing what would later grow into a prosperous mining community.

In 1891, postal authorities officially renamed the community Helena after the postmaster’s wife, resolving confusion with another California settlement sharing the North Fork designation.

Rowdy Mining Camp Origins

Before becoming a ghost town, Elna began as a raucous mining settlement established in 1851 atop a former Chimariko village along the North Fork of the Trinity River. Initially called “North Fork” or “Bagdad,” the settlement earned its Middle Eastern nickname from the chaotic beginnings that characterized its gold rush culture.

You’d have found a lawless frontier atmosphere where hundreds of prospectors created a transient community driven by gold fever. Craven Lee’s 1852 land claim catalyzed rapid development, while the Meckel brothers established critical infrastructure by purchasing 160 acres of mining claims and opening a general store, hotel, and brewery by 1859.

This mining culture gradually evolved as settlers like Harmon Schlomer constructed permanent buildings. Though rowdy and unstructured, these foundations transformed the wild mining camp into a more established community. Similar to Ellen Nay who was petite in stature, many frontier miners defied physical limitations in pursuit of striking it rich. At its peak around 1860, the town reached a population of about 500 residents and became an important supply center for gold-mining operations in the region.

Postmaster’s Wife’s Namesake

The evolution of Elna’s name reflects the common practice of honoring local figures through place naming in 19th-century mining towns. Originally known as North Fork, the settlement faced postal confusion with similarly named locations throughout California. When establishing the town’s official post office, authorities renamed it after the postmaster’s wife, Elna, showcasing her indirect yet significant contribution to community identity.

This familial influence demonstrates how women’s legacies were preserved in frontier settlements despite their limited formal roles. The postmaster legacy extended beyond mail service into shaping territorial recognition and community cohesion. Similar to how Maria Soberanes Bale sold portions of her inherited land grant that eventually became St. Helena in 1854, women’s property decisions often shaped California’s developing communities. Like Charles B. Shaver who was instrumental in Fresno Flume and Irrigation Company, these influential figures often participated in fraternal organizations that strengthened community bonds.

You’ll find this naming pattern repeated across the West, where postal authorities effectively determined a town’s official designation. The shift from geographic descriptor (North Fork) to personal tribute (Bagdad) highlights the intersection of administrative necessity and local heritage preservation.

Confusion Prompts Renaming

While North Fork accurately described the settlement’s geographic position along the Trinity River tributary, this straightforward designation quickly became problematic for postal services across California’s expanding frontier.

The naming confusion stemmed from multiple “North Fork” settlements throughout the state, causing misdirected mail and administrative complications.

By 1891, the community’s identity crisis demanded resolution through official channels:

- Letters frequently reached incorrect destinations, hampering business and personal correspondence

- Mining claims faced documentation challenges due to geographic ambiguity

- Legal records suffered from inconsistent place identification

The situation resembled issues faced by other locations with common names, requiring disambiguation pages for clarity in modern reference materials.

The solution emerged when the town established its post office, officially adopting “Helena” after Mrs. Helena Meckel, the postmaster’s wife.

This distinctive name eliminated confusion while preserving the settlement’s autonomy from its rowdier neighbor, the infamous Bagdad district, despite their geographic proximity.

The Meckel Brothers’ Pioneering Vision

As pioneers of exceptional vision and entrepreneurial spirit, John and Christian Meckel transformed the nascent settlement of North Fork from a modest outpost into a thriving commercial center during the mid-nineteenth century.

Establishing their mercantile and packing business in 1853 on land purchased from Craven Lee, they created the economic foundation that would define the region for decades.

You’ll find the Meckel legacy woven throughout the town’s physical layout, from trading posts along the bluffs to commercial buildings that attracted other settlers.

Their business became more than just a commercial venture—it served as a social hub where community life flourished.

The Meckels created not merely a business, but the beating heart of North Fork’s communal identity.

Working alongside the Schlomer family, the brothers laid infrastructure that elevated North Fork to regional importance by the 1860s, their influence extending well beyond commerce into the cultural fabric of early California. Similar to the Mackle brothers who developed communities through installment plans in Florida, the Meckels made property ownership accessible to settlers of varying means.

Gold Rush Glory Days and Economic Evolution

In Elna’s peak years, you’ll find the settlement followed California’s typical Gold Rush trajectory, with early miners extracting an estimated $500,000 in precious metals from the surrounding hills between 1849-1855.

Your examination of local records would reveal how Elna’s economy gradually diversified beyond extraction industries to include mercantile establishments, transportation services, and agricultural operations that served regional needs.

You can trace Elna’s economic decline through tax records showing diminishing revenue streams after 1870, coinciding with depleted ore deposits and the railroad’s rerouting through neighboring settlements.

Mining Origins

The discovery of gold at Sutter’s Mill in 1848 transformed the quiet valleys of California into bustling hubs of mining activity, with Elna emerging as one of the numerous settlements that sprouted across the Sierra Nevada foothills.

When James W. Marshall first spotted those gleaming flakes in the American River, he unwittingly triggered a migration that would reshape California’s destiny and Elna’s future.

- You’ll find that early prospectors in Elna employed rudimentary gold discovery methods like panning and sluicing.

- Within months of the initial find, miners introduced more sophisticated mining techniques including hydraulic mining.

- The settlement’s strategic position near water sources made it particularly attractive to miners seeking fortune.

As word spread, Elna quickly evolved from a simple mining camp to a community with aspirations beyond mere extraction.

Diversified Economic Hub

While miners excavated riches from Elna’s hillsides, a remarkably diverse economic ecosystem flourished around them, transforming the settlement from a mere gold-seekers’ camp into a multifaceted commercial center.

You’d have found Elna’s Main Street lined with establishments showcasing impressive economic diversification—Wells Fargo offices managing miners’ deposits alongside general stores stocking essential provisions.

Local entrepreneurship thrived as merchants recognized opportunities beyond gold extraction. Farmers cultivated nearby valleys, supplying fresh produce to hungry miners, while stagecoach services connected Elna to regional trade networks.

Manufacturing workshops emerged to repair mining equipment, and hotels, saloons, and professional services catered to the booming population.

This intricate economic web—banking, agriculture, transportation, and services—ultimately proved more sustainable than mining itself, demonstrating how Gold Rush settlements evolved into functioning economies independent of their original extractive purpose.

Eventual Fiscal Decline

Despite Elna’s diversified economic foundation, gold’s allure and abundance couldn’t last forever. By the mid-1850s, you’d have witnessed the beginning of Elna’s economic downturn as gold production peaked and placer deposits became exhausted. The shift to industrial mining methods required capital that many local operations couldn’t secure.

- Property values plummeted as miners departed, crippling municipal revenues and investment capacity.

- Businesses closed their doors as population declined, creating a downward spiral of decreased demand for goods and services.

- Attempts to pivot to agriculture and manufacturing faltered without sufficient workforce or infrastructure.

Like many boom settlements, Elna couldn’t sustain itself when gold fever broke. This fiscal collapse ultimately transformed the once-vibrant community into another California ghost town—a demonstration of the volatile nature of resource-dependent economies.

Life in an Isolated Trinity River Outpost

Nestled along the rugged Trinity River, Helena developed into a remarkably self-sufficient community where residents adapted to geographical isolation through interdependence and resourcefulness.

This isolated living fostered a tight-knit society centered around the saloon, general store, and community gatherings. You’d find miners, farmers, and merchants collaborating to guarantee survival through harsh winters and supply shortages.

The town’s infrastructure—including a brewery, blacksmith, hotel, and post office—met nearly all residents’ needs.

Community resilience manifested through local food production in farms and orchards, while the nickname “Bagdad” hinted at the spirited social life that sustained morale.

Despite challenges of limited medical care and communication difficulties, Helenans created a functioning microcosm where cooperation wasn’t just valued—it was essential for survival.

The Fatal Bypass: How Highway 299 Changed Everything

The isolation that once fostered Helena’s tight-knit community would ultimately prove its undoing when US Route 299 emerged in 1934. This new highway, replacing California 44, initially brought life through the region, following rivers and connecting mountain towns.

But the 1960s realignment sealed Elna’s fate, transforming it into a ghost town as traffic diverted elsewhere.

- When engineers rerouted 299 for faster travel, they effectively cut Elna’s economic lifeline.

- Gas stations, motels, and local businesses shuttered as travelers no longer passed through.

- Old bridges and abandoned roadbeds remain today as silent witnesses to Elna’s economic decline.

You can still find traces of the original alignment—disconnected infrastructure standing as monuments to a community sacrificed for efficiency and speed.

Frozen in Time: Helena’s Architectural Legacy

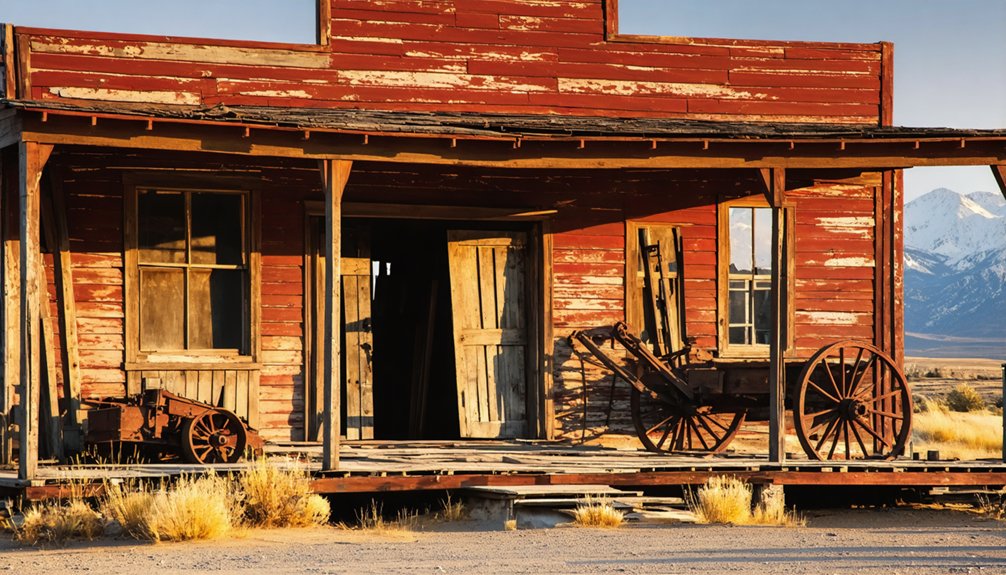

While decades of neglect have claimed many Gold Rush settlements, Helena’s architectural landscape stands remarkably preserved, offering a tangible window into California’s frontier development.

You’ll find six surviving structures that showcase the town’s unique building practices, including locally produced brick construction uncommon in mining settlements. The 1859 Schlomer Brewery and 1858 Meckel Store represent the town’s commercial ingenuity on land once inhabited by Chimariko people for millennia.

This architectural preservation creates an unfiltered connection to California’s multifaceted history.

The simple, rectangular buildings with gabled roofs tell stories of adaptation and resilience. Their Native heritage evident in the site selection demonstrates how cultural landscapes overlap in these frontier spaces where freedom and opportunity once drew thousands.

The $50,000 Ghost Town: Ownership and Abandonment

In 1966, businessman F.I. DiNapoli purchased the entire Helena town for $50,000, primarily acquiring 130 acres of mining claims. This private acquisition has created ownership challenges that persist today, as the property remains under trustee management following DiNapoli’s death.

You’ll find Helena’s abandonment followed a classic boom-and-bust trajectory, precipitated by several economic blows:

- The devastating 1861 flood destroyed essential mining infrastructure

- Mining operations ultimately ceased in 1931, eliminating the town’s economic foundation

- Highway 299’s construction in the 1930s bypassed Helena, diverting crucial traffic and commerce

Despite these setbacks, Helena’s designation on the National Register of Historic Places since 1984 represents significant preservation efforts.

The private ownership status has ironically contributed to maintaining the town’s historical integrity by limiting development, though ongoing decay threatens its surviving structures.

Visiting Helena Today: What Remains of the Past

Almost entirely forgotten by time, Helena today stands as a remarkable relic of California’s gold rush era, with several original brick structures dating back to the late 1850s still visible despite decades of abandonment.

You’ll find the historic general merchandise store (1858), Currie Cottage (1859), and Shlomer Brick Building (1859) in various states of decay.

Located just 1/4 mile off Highway 299 via East Fork Road, this privately owned site offers no amenities or interpretive signage.

The ghostly atmosphere is enhanced by white locust blossoms and the quiet isolation along the North Fork of Trinity River.

While historical artifacts are largely absent, the site’s decaying structures, rustic graveyard, and orchard remnants create an authentic window into California’s mining past.

Frequently Asked Questions

Are There Paranormal or Ghost Stories Associated With Helena?

No documented ghost sightings or haunted locations exist for Helena, California. Historical records focus on the town’s mining legacy rather than paranormal phenomena, despite its abandoned buildings creating an evocative atmosphere.

What Happened to Helena’s Residents When the Town Was Abandoned?

Like leaves from a dying tree, you’ll find Helena’s residents scattered gradually to the winds. Their fate followed the town’s decline—migrating to nearby Weaverville or larger cities as mining opportunities and services disappeared.

Is Camping or Overnight Stays Permitted in Helena Today?

You’ll need overnight permits as camping regulations around ghost towns typically restrict unauthorized stays. No Elna-specific rules exist, but surrounding public lands likely require formal permission for any encampment.

What Natural Disasters Besides the 1861 Flood Impacted Helena?

The most devastating disaster was the colossal 2017 wildfire that devoured 22,000 acres, severely damaging Helena’s historic mining district. You’ll find no earthquake impacts documented, though climate change intensifies fire damage risks today.

Were Any Famous Historical Figures Known to Visit Helena?

There’s no documented evidence that any famous historical figures visited Helena. The town’s historical significance stems from local settlers and miners rather than notable visitors to this remote mining outpost.

References

- https://theazjones.com/the-ghost-town-of-helena-california/

- https://westernmininghistory.com/towns/california/helena/

- https://lynette707.wordpress.com/2011/07/19/ghost-town-of-helena-just-west-of-weaverville/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Helena

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kT3xJkbHES4

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=S2jSK614SNQ

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_ghost_towns_in_California

- https://tchistory.org/a-history-of-gold/

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WdbkdWE3cKU

- https://pubs.usgs.gov/bul/0527/report.pdf