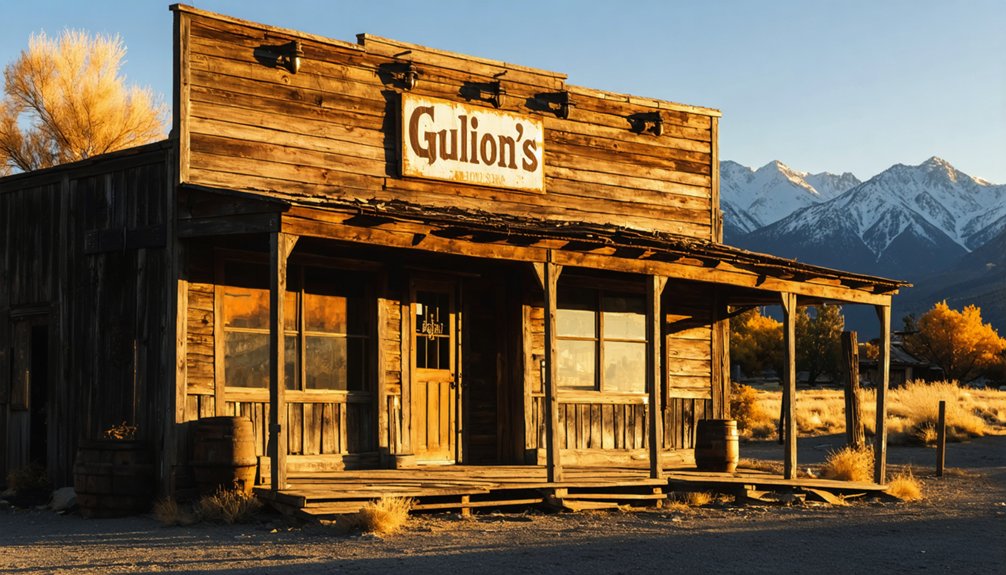

Gullion’s Bar was a significant gold mining camp established along California’s Salmon River in 1850. You’ll find it was once a bustling community where miners used evolving techniques from simple panning to complex sluice systems. The settlement thrived briefly before declining in the mid-1850s as gold deposits diminished. Today, preservation efforts include GPS mapping, museum exhibits, and virtual reconstructions that capture this forgotten piece of Trinity County’s gold rush heritage.

Key Takeaways

- Gullion’s Bar was a significant gold mining camp established in Trinity County, California during the 1850 gold rush.

- The settlement thrived briefly with diverse mining techniques before declining as placer deposits were exhausted in the mid-1850s.

- Residents endured harsh frontier conditions while creating community infrastructure like a two-mile water ditch.

- The remote location prevented development of alternative industries after gold depletion, leading to abandonment.

- Today, preservation efforts include GPS mapping, drone surveys, museum exhibits, and digital reconstructions of this California ghost town.

Gold Rush Origins and Settlement (1850)

When gold was discovered along California’s Salmon River in 1850, Gullion’s Bar emerged as one of Trinity County’s most productive mining camps during the Northern California gold rush. The settlement quickly gained historical significance alongside other prominent camps like Negro Flat, Bestville, and Sawyers Bar, establishing itself within the gold-rich landscape that attracted thousands to this remote region.

You’d have found a diverse community of American prospectors and international immigrants engaged in placer mining—extracting gold from river gravels with relatively simple techniques. The camp grew to include essential facilities and services supporting miners’ needs. Like many boomtowns of this era, Gullion’s Bar witnessed the transformation of mining techniques from simple panning to more complex methods using cradles and rockers as surface gold became harder to find. The lawlessness typical of mining camps was evident at Gullion’s Bar, where disputes over claims were resolved through local rules developed in the absence of formal legal systems.

Life Along the Salmon River Mining Camp

Daily existence at Gullion’s Bar centered around the harsh realities of frontier life that shaped all aspects of the mining community’s social fabric.

You’d have found yourself living in a simple cabin or tent, relying on the general store for supplies while facing daily challenges of poor sanitation and unpredictable weather.

Community interactions followed the Mexican Alcalde system of informal justice, with miners’ courts settling disputes when competition over claims turned tense.

Your survival depended on cooperation—joining forces to build the two-mile water ditch that served both mining operations and domestic needs by 1868.

When cash ran short, you’d barter labor or goods with neighbors.

Evening gatherings provided relief through gambling, music, and storytelling after long days working the Salmon River placers.

Mining Techniques and Economic Boom

As gold fever gripped California in the 1850s, Gullion’s Bar quickly emerged as one of Trinity County’s most productive mining settlements through the widespread adoption of placer mining techniques.

You’d have seen miners wielding pans, rockers, and sluice boxes to separate gold from river gravels, gradually evolving from solo prospecting to organized operations.

By 1868, a sophisticated two-mile water ditch transformed the settlement’s capabilities, enabling more efficient processing methods. What began as simple hand-held tools eventually incorporated long toms for increased efficiency.

While hydraulic techniques were common regionally, Gullion’s Bar primarily relied on traditional placer mining. Miners endured backbreaking labor from sunrise to sunset, six days a week, as they moved dirt in search of valuable gold particles. This infrastructure investment reflected the camp’s economic significance and adaptation to local conditions.

The discovery sparked a classic boom-bust cycle, with the initial rush creating rapid growth followed by decline, until the 1858 Nordheimer’s Creek strike briefly revitalized the area’s fortunes.

The Decline and Abandonment

The once-thriving settlement of Gullion’s Bar began its inevitable decline during the mid-1850s, when the rich placer deposits that had sustained its economy gradually disappeared beneath miners’ persistent efforts.

You’ll find that economic decline accelerated as mining costs outpaced diminishing returns, forcing residents to seek opportunities elsewhere.

Despite a brief revival following the 1858 Nordheimer Creek strike, the camp couldn’t sustain its population without economic diversification beyond gold extraction.

Social instability followed as businesses closed and families departed, weakening community bonds.

The remote location—initially an advantage for miners—became a liability that prevented alternative industries from developing.

By 1868, though infrastructure remained, productivity couldn’t support settlement, and administrative changes further isolated the area. Like Bestville in Siskiyou County, Gullion’s Bar witnessed frequent changes in county jurisdiction that complicated governance and record-keeping. The pattern mirrored other California ghost towns where resource depletion inevitably led to abandonment.

Eventually, nature reclaimed what was once a bustling frontier outpost.

Preserving Gullion’s Bar’s Legacy Today

While Gullion’s Bar gradually faded into obscurity by the late 1860s, its historical significance hasn’t diminished with time.

Today, preservation efforts employ cutting-edge technologies like GPS mapping and drone surveys to document remaining artifacts before nature reclaims them entirely.

You’ll find robust community engagement through local museum exhibits, interpretative trails, and volunteer maintenance programs that connect residents with their gold rush heritage.

Schools participate in specialized curricula and field trips to the site, where protective signage educates visitors on respectful exploration.

Digital preservation initiatives have revolutionized access to Gullion’s Bar history.

Virtual reality reconstructions transport you to the 1850s mining camp, while online databases compile mining records and oral histories.

These efforts, supported by state preservation laws and heritage grants, guarantee this slice of California’s pioneering spirit endures for future generations.

Frequently Asked Questions

Were Any Notable Crimes or Outlaws Associated With Gullion’s Bar?

Despite persistent tales you might’ve heard, historical records show no notable crimes or outlaws associated with Gullion’s Bar. The camp’s criminal history remains undocumented compared to other Gold Rush settlements.

What Indigenous Tribes Inhabited the Area Before the Mining Settlement?

You’d find the Karuk and Shasta tribes established around Gullion’s Bar before miners arrived. Their tribal history centered on river-based native customs, including salmon fishing essential to their semi-nomadic, autonomous way of life.

How Did Seasonal Weather Patterns Affect Mining Operations?

With 85% of mining operations halted during dry spells, your success depended on water availability. Weather impact created significant mining challenges, prompting your two-mile ditch system construction by 1868 to overcome seasonal constraints.

Are There Any Accessible Ruins or Artifacts Remaining Today?

You’ll find virtually no accessible ruins during ghost town exploration of Gullion’s Bar. Unlike nearby sites with historical preservation efforts, no artifacts or structures are documented at this barren former placer mining location.

Did Gullion’s Bar Have Connections to Chinese Immigrant Mining Communities?

You’ll find clear evidence of Chinese labor throughout Siskiyou County’s mining history, though direct records for Gullion’s Bar are limited. Cultural exchange likely occurred as Chinese miners worked nearby hydraulic operations along the Klamath.

References

- https://roadtrippers.com/magazine/gin-mill-seneca-california/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_ghost_towns_in_California

- https://npshistory.com/nature_notes/yose/v27n1.pdf

- https://en.everybodywiki.com/Wingate_Bar

- https://www.familysearch.org/en/wiki/Siskiyou_County

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/California_gold_rush

- https://tchistory.org/a-history-of-gold/

- https://goldbroker.com/news/brief-history-gold-rush-3177

- https://www.mariposacounty.org/DocumentView.asp?DID=3103

- https://m.famousfix.com/list/settlements-formerly-in-trinity-county-california