You’ll discover America’s industrial heritage through abandoned towns like Danville’s textile mills, Johnstown’s steel works, and Muncie’s auto plants. These sites showcase manufacturing’s decline since 1980, with over 100,000 shuttered factories. From Centralia’s perpetually burning ground to Kennecott’s copper complex, Youngstown’s steel ruins, and Bodie’s gold rush remains, each location tells a unique story of boom and bust. These preserved artifacts reveal deeper insights into America’s economic transformation.

Key Takeaways

- Danville, Virginia features the historic Dan River Mills complex, which employed 14,000 workers before closing in 2006 due to global competition.

- Centralia, Pennsylvania became a ghost town after an underground coal fire started in 1962, creating toxic gases and unstable ground.

- Kennecott, Alaska contains a preserved copper mining complex with a 14-story concentrator mill and 45 historic buildings from 1907-1925.

- Thurmond, West Virginia transformed from a bustling coal shipping hub processing more freight than Cincinnati to an abandoned railroad town.

- Ludlow, Colorado preserves labor history through its abandoned mining structures and granite monument commemorating the 1914 massacre.

The Textile Legacy of Danville, Virginia

While many American industrial towns have faded into obscurity, Danville, Virginia’s textile heritage stands as a symbol of the transformative power of the cotton mill era.

You’ll find the roots of this transformation in the 1882 establishment of Riverside Cotton Mills, which later became Dan River Mills and employed over 14,000 workers in a city of just 40,000. The mill’s simplified Gothic Revival design set new standards for industrial architecture.

The essence of mill town life centered around company-built villages, where workers’ daily routines revolved around textile production. Archaeological excavations along Front Street have uncovered millworker households that provide invaluable insights into daily life. This economic transformation reached its peak when Mill No. 8 emerged as one of America’s most modern facilities.

Mill life pulsed through company villages, where the rhythm of textile machinery dictated the daily dance of workers’ lives.

However, by 2006, global competition forced the mills’ closure, devastating the local economy. Today, only Dan River Falls remains as a representation of Danville’s industrial past, while ongoing preservation efforts seek to balance economic renewal with historical remembrance.

Johnstown’s Steel Mill Remnants

When Cambria Iron Company established its operations in Johnstown in 1852, it marked the beginning of an industrial powerhouse that would shape American steel production for over a century.

You’ll find that Cambria Iron quickly became a national leader, pioneering innovative techniques that influenced giants like Bethlehem Steel and U.S. Steel.

Today, you can explore the remnants of this steel heritage at the preserved Lower Works, which dates back to 1864.

The site’s rich history includes its historic Blacksmith Shop, featuring an octagonal ceiling and preserved early 20th-century tools.

Located at the intersection of three river valleys, the city’s unique geography made it an ideal location for industrial development.

As one of only two American steel mills designated as a National Historic Landmark, it’s a reflection of Johnstown’s industrial might.

The site’s transformation through multiple owners – from Cambria Iron to Midvale Steel, and finally Bethlehem Steel – mirrors the rise and fall of America’s steel industry, until its final closure in 1992.

Muncie’s Manufacturing Ghost Towns

The Gas Boom of 1880 transformed Muncie into a manufacturing powerhouse, drawing 162 factories to Indiana’s “Gas Belt” region.

You’ll find the city’s industrial heritage deeply rooted in companies like Ball Brothers Glass, which produced 30 jars per minute, and the GM Chevrolet Plant that became essential to America’s automotive industry.

Manual transmission production defined the city’s automotive sector until operations moved to Mexico in the late 1990s.

Today, you’re witnessing Muncie factories in various states of abandonment.

The once-bustling Chevrolet Plant was demolished in 2017, while BorgWarner’s closure in 2009 marked the end of an era.

Like the historic Elizabethtown Mill, these industrial sites fell victim to changing economic conditions.

Foreign competition and technological evolution have stripped away an estimated 20,000 auto industry jobs since 1999.

While some sites await redevelopment, others stand as silent monuments to Muncie’s manufacturing past.

The city’s transformation from industrial giant to post-industrial landscape reflects broader changes in America’s economic structure.

The Burning Ground of Centralia

Deep beneath Centralia, Pennsylvania’s surface, an underground inferno has smoldered relentlessly since 1962, transforming a once-thriving mining town into America’s most infamous ghost town.

The disaster began when borough officials ignited a landfill fire that breached an incomplete clay barrier, reaching abandoned coal seams below. Despite numerous fire containment attempts – including flooding mines and installing fly ash barriers – the blaze defied control, forcing nearly all 1,500 residents to abandon their homes. This underground blaze attracted visitors who wanted to see the ghost town status created by the disaster.

You’ll find Centralia’s toxic legacy in the destabilized ground, deadly gases seeping through fissures, and an 8-mile stretch of burning coal that could persist for centuries.

The disaster serves as a stark reminder of industrial negligence, with failed suppression efforts and environmental damage leaving behind a permanently altered landscape that continues threatening safety through sinkholes and subsidence.

Temperatures in the burning underground zones reach over 1,000 degrees Fahrenheit, creating an inhospitable environment that releases lethal carbon monoxide through surface vents.

Kennecott’s Copper Mining Heritage

You’ll find an impressive scale of copper mining operations at Kennecott, where peak production in 1916 yielded ore worth $32.4 million and ranked among America’s top copper producers. To avoid confusion with similarly named locations, the site is listed under separate Wikipedia entries.

The site’s preserved industrial architecture includes the original mill, railway infrastructure, and company town buildings that showcase early 20th-century mining technology and town planning. The development required constructing a 196-mile railroad line to transport the valuable copper ore to market.

What began as a rich copper deposit discovered in 1900 near Alaska’s Kennecott Glacier now stands as a National Historic Landmark, where the environmental impacts of intensive mining operations remain visible in the surrounding landscape.

Mining Operations and Scale

Spanning nearly three decades from 1911 to 1938, Kennecott’s copper mining operations in Alaska’s Wrangell St. Elias National Park represented one of America’s most ambitious industrial ventures.

You’ll find the scale of copper extraction was staggering – producing 1.183 billion pounds from 4.6 million tons of ore, generating over $200 million in revenue.

The mining infrastructure sprawled across five distinct mines – Bonanza, Jumbo, Mother Lode, Erie, and Glacier – connected by an intricate network of aerial tramways.

To support these operations, you’d have seen a sophisticated 196-mile railway system linking Kennecott to Cordova, plus steamship connections to Tacoma’s smelters.

The initial investment of $25 million (equivalent to $730 million today) established what would become America’s largest copper supplier by the 1930s.

Preserved Industrial Architecture

While many industrial sites from America’s mining era have vanished, Kennecott’s preserved copper mining complex stands as the nation’s premier example of early 20th-century industrial architecture.

You’ll find this National Historic Landmark‘s architectural significance reflected in its distinctive red and white wooden structures, spanning 7,700 acres of industrial heritage.

The historic preservation efforts maintain:

- The imposing 14-story concentrator mill, dominating the skyline

- Forty-five main buildings and twenty-five outbuildings, all constructed between 1907-1925

- Essential community structures including the hospital, schoolhouses, and recreation hall

- Original industrial features like utilidors, flumes, and water systems

The National Park Service’s adaptive reuse program has transformed key buildings into modern spaces while protecting their historic character, ensuring you can experience authentic early 20th-century industrial design firsthand.

Environmental Legacy Today

Despite its preserved architectural grandeur, Kennecott’s copper mining legacy has left a complex environmental burden that persists today.

You’ll find extensive toxic contamination from heavy metals and acid mine drainage affecting soil, water, and wildlife habitats throughout the region. The scale of pollution requires treating 2.7 billion gallons of contaminated water annually, with cleanup efforts projected to continue for at least 40 years.

Environmental restoration faces significant challenges within Wrangell-St. Elias National Park’s remote setting. The EPA’s Superfund program oversees thorough investigations while the National Park Service conducts ongoing environmental studies.

These efforts aim to protect endangered ecosystems, particularly salmon habitats threatened by elevated metal concentrations and acidic conditions. While the site stands as a National Historic Landmark, its industrial past continues to demand substantial resources for long-term remediation.

Thurmond’s Railroad Glory Days

You’ll find Thurmond’s rise to prominence as a major coal shipping hub reflected in its peak operations during the 1910s-1920s, when the town processed more freight tonnage than Cincinnati and Richmond combined.

The town’s strategic location and extensive railroad infrastructure, including the iconic 840-foot Thurmond Bridge, enabled it to serve up to 15 passenger trains daily while handling massive coal shipments from surrounding Appalachian mines.

Today, you can explore the well-preserved depot building and rail yard remnants that stand as evidence to Thurmond’s industrial heritage, now drawing visitors as part of the New River Gorge National Park.

Peak Coal Transport Era

The bustling rail town of Thurmond dominated Appalachian coal transport from 1880 to 1950, establishing itself as the region’s most prolific shipping depot.

During Thurmond’s economic boom, the town’s strategic location made it the powerhouse of the Chesapeake & Ohio Railway, surpassing revenue generation of major cities like Cincinnati and Richmond combined.

- You’ll find that by 1910, Thurmond’s rail yards processed more freight tonnage than any other depot in the New River Gorge.

- The town served as a critical assembly point, coordinating coal cars from numerous surrounding mines.

- At its peak in 1930, Thurmond’s banks were West Virginia’s wealthiest due to coal baron patronage.

- Thurmond’s decline began in 1917 with rising road transport, followed by devastating fires in 1922 and 1930, and finally, the 1950s shift to diesel locomotives.

Historic Railroad Infrastructure Remains

Standing as a demonstration to America’s industrial might, Thurmond’s railroad infrastructure remains showcase the engineering prowess of early 20th-century rail development.

You’ll find the iconic 840-foot bridge, built in 1915, combining truss and deck plate girder design with concrete piers – a representation of railroad heritage that’s still intact today. The restored depot, now a visitor center within New River Gorge National Park, anchors the site’s industrial preservation efforts.

Throughout the yards, you can trace the physical remnants of coal loading facilities and rail sidings that once handled massive freight operations.

While most structures stand abandoned, they’re far from forgotten. The historic hotels and shops along the rail line, coupled with Amtrak’s continued request-stop service, connect you directly to Thurmond’s industrial legacy.

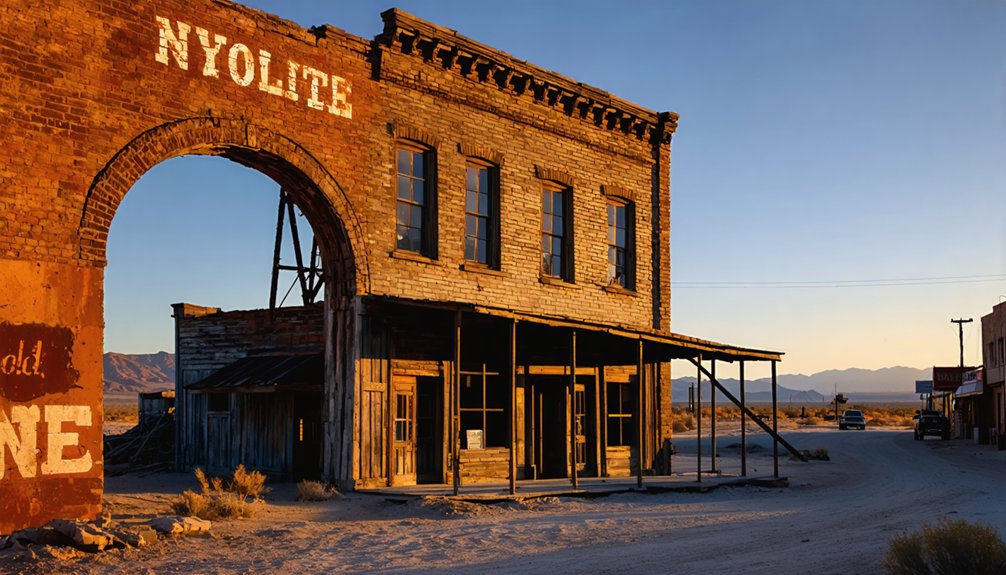

Modern Ghost Town Tourism

Once a bustling railroad metropolis that processed more freight than Cincinnati and Richmond combined, Thurmond now draws visitors as a carefully preserved ghost town within New River Gorge National Park.

As one of America’s most authentic modern ghost towns, you’ll find a remarkable blend of industrial tourism and historical preservation that captures the rise and fall of America’s railroad era.

Exploring the haunting history of abandoned towns offers a unique glimpse into forgotten lives and their stories. Each structure stands as a testament to the passage of time, whispering secrets of those who once called these places home. Visitors are often left with a sense of nostalgia and curiosity about the lives that unfolded within those walls.

- Visit the restored 1904 passenger depot, now serving as a museum and visitor center

- Explore stabilized commercial buildings maintained by the National Park Service

- Catch an Amtrak train at one of the few remaining flag stops in the country

- Participate in annual events like the triathlon that bring hundreds to this historic site

The town’s transformation from industrial powerhouse to preserved artifact exemplifies the evolution of America’s industrial heritage into cultural tourism destinations.

Youngstown’s Steel Industry Collapse

When Youngstown’s Campbell Works shuttered its doors on September 19, 1977, it triggered a catastrophic chain reaction that would define America’s industrial decline.

You’ll find that 5,000 workers lost their jobs without warning, marking the birth of the Rust Belt era. Despite this blow, steelworker resilience emerged as labor unions and religious leaders united to fight for community ownership of the facility.

Though the Carter administration backed a worker-community ownership plan that could’ve saved 4,000 jobs, the initiative ultimately failed due to insufficient capital.

Here Chronicle

You’re witnessing the aftermath today: Youngstown has lost two-thirds of its population since the 1970s. The city’s transformation from industrial powerhouse to rust belt symbol reveals how rapid deindustrialization can devastate communities when traditional economic models collapse without viable alternatives.

Bruceton’s Lost Textile Empire

While Youngstown exemplified the collapse of steel manufacturing, Bruceton, Tennessee tells an equally compelling story of America’s lost textile industry.

In the late 20th century, the Henry I. Siegel Company (H.I.S.) served as Bruceton’s economic anchor, establishing itself among Carroll County’s top employers through women’s jeans production.

- The company’s workforce development programs created sustainable jobs, training locals in garment manufacturing skills essential to the region’s growth.

- Railroad infrastructure facilitated robust supply chains, connecting Bruceton’s textile operations to broader markets.

- Globalization triggered a devastating 17-year decline as operations moved to lower-cost regions.

- Today’s abandoned mills stand as silent sentinels of Bruceton’s industrial past, while the town’s small population (1,507 in 2020) reflects the lasting impact of textile manufacturing’s departure.

The Mining Ruins of Ludlow

The blood-soaked soil of Ludlow, Colorado stands as one of America’s most poignant industrial ghost towns, forever marked by the 1914 massacre that claimed two dozen lives during the Colorado Coalfield War.

You’ll find scattered remnants of this once-thriving mining community, where 1,200 inhabitants fought against the oppressive conditions imposed by Colorado Fuel & Iron.

The site’s dilapidated structures and industrial artifacts tell the story of workers who dared to strike against Rockefeller’s empire.

Today, you can explore the archaeological remains that validate the strikers’ struggles, while a granite monument, erected by the United Mine Workers in 1918, honors those who fell.

The Ludlow Massacre site, now a National Historic Landmark, preserves vital evidence of America’s labor rights movement and the true cost of industrial capitalism.

Bodie’s Gold Rush Relics

Unlike Ludlow’s labor struggles, Bodie stands as America’s most intact monument to gold rush prosperity and decline.

Bodie’s preserved ruins tell a unique story of the American West – a tale of striking gold and slow fade into silence.

You’ll find this California ghost town preserved in “arrested decay,” showcasing authentic gold mining techniques from the 1800s. The site’s remarkable collection of Bodie memorabilia remains exactly as miners left it when operations ceased in the 1940s.

- Explore over 110 original wooden structures that survived two devastating fires

- Witness the evolution of mining technology, from early stamp mills to cyanide processing

- View building interiors stocked with period artifacts, frozen in time

- Experience a town that produced $70 million in precious metals over its lifetime

Today’s preserved district offers you unparalleled insights into boomtown architecture and industrial archaeology, making it the most authentic gold rush site in America.

Frequently Asked Questions

How Safe Is It to Explore Abandoned Industrial Towns Without Official Permission?

With 94% of industrial ruins being private property, you’re risking severe legal consequences and life-threatening hazards. You can’t take proper safety precautions without permits and site knowledge.

What Photography Equipment Is Best Suited for Capturing Industrial Ruins?

You’ll need wide-angle and telephoto lens choices, a sturdy DSLR with high ISO capability, and portable LED lighting techniques. Don’t forget your tripod for those dramatic long-exposure shots.

Which Abandoned Industrial Towns Still Have Active Security Patrols?

You’ll find active security measures in Centralia, Pennsylvania, Bodie, California, and Kennecott, Alaska, with regular patrol frequency. Thurmond, West Virginia maintains seasonal patrols during peak tourist periods.

Are There Guided Tours Available for Any of These Locations?

While not all sites allow access, you’ll find guided exploration options at Sloss Furnaces and New Haven’s heritage trails, where experts share historical significance through structured tours highlighting industrial technology.

Can Visitors Take Artifacts or Souvenirs From These Abandoned Sites?

You can’t legally remove artifacts from these sites due to property rights and preservation laws. Ethical considerations also require leaving items in place to maintain historical integrity.

References

- https://www.industryweek.com/talent/article/22028380/the-abandonment-of-small-cities-in-the-rust-belt

- https://www.manufacturing.net/labor/blog/22879058/the-abandonment-of-cities-and-towns-in-the-heartland

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wikipedia:WikiProject_Ghost_towns

- https://www.loveexploring.com/gallerylist/131658/abandoned-in-the-usa-92-places-left-to-rot

- https://vocal.media/01/1000-abandoned-places-in-america-a-journey-through-time-and-ruins

- https://plantandmachinery.caboodleai.net/article/166865/20-forgotten-industrial-sites-in-the-u.s.-that-are-eerily-beautiful

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ghost_town

- https://www.abandonedamerica.us/abandoned-business-and-industry

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_ghost_towns_by_country

- https://devblog.batchgeo.com/ghost-towns/