You’ll discover America’s most fascinating abandoned mining villages, from Bodie, California’s $38 million gold bonanza (1877-1882) to Kennecott, Alaska’s $200 million copper empire (1911-1938). St. Elmo, Colorado produced 220,000 gold ounces, while Dearfield emerged as a pioneering Black farming community. These ghost towns showcase preserved mills, saloons, and worker housing from Garnet, Montana to Eckley’s coal region. Each site’s artifacts reveal untold stories of America’s mineral extraction heritage.

Key Takeaways

- Bodie, California features 2,000 preserved buildings from its gold mining heyday, with 200 structures maintained in “arrested decay” for tourism.

- Kennecott, Alaska houses America’s richest copper deposits and includes a restored 14-story concentration mill within Wrangell-St. Elias National Park.

- St. Elmo, Colorado maintains 40 original buildings from its silver and gold mining era, showcasing authentic frontier mining architecture.

- Calico, California contains remnants of its 1880s silver boom, when 3,000 residents extracted up to $20 million worth of ore.

- Steins, New Mexico stands abandoned since 1944, featuring remains of hotels and saloons from its quarry mining operations.

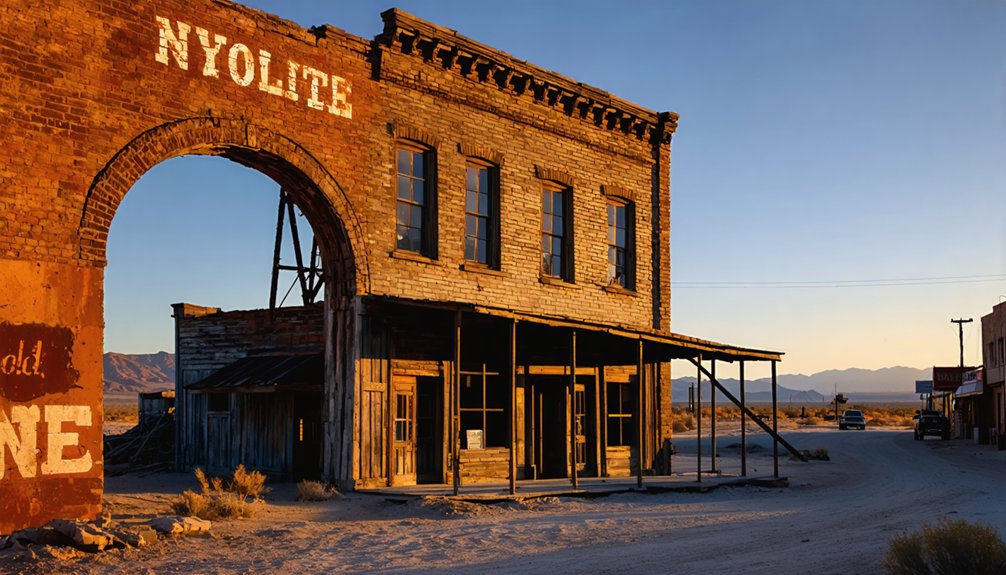

The Gold Rush Legacy of Bodie, California

While prospectors discovered gold in the Bodie area in 1859, the town’s namesake W.S. Bodey tragically perished in a November blizzard that same year.

You’ll find his legacy lives on in what became California’s most remarkable ghost town. The settlement’s true economic impact emerged in 1876 when the Standard Mining Company struck a major gold deposit, transforming Bodie from a struggling camp into a booming metropolis of 8,500 residents.

Mining techniques advanced as nine quartz mills operated 159 stamps, yielding over $38 million in gold production between 1877-1882. The community dynamics featured over 60 saloons and 2,000 buildings, though Bodie’s prosperity proved short-lived. Harsh winter conditions at the elevation of 8,375 feet made life challenging for residents. The constant need for lumber led to the construction of a narrow gauge railroad connecting Bodie to Mono Mills in 1881.

Today, preservation efforts maintain nearly 200 structures in “arrested decay,” making this historic mining town one of America’s most authentic tourist attractions.

Kennecott: Alaska’s Copper Kingdom

Today you’ll find America’s most remarkable copper mining heritage preserved in the remote Alaskan wilderness of Kennecott, where from 1911 to 1938 the nation’s richest copper deposits yielded ore worth $200 million ($2.5-4 billion today).

You’re walking through a National Historic Landmark District within Wrangell-St. Elias National Park, where the restored mill town showcases the ambitious scale of early 20th-century industrial mining with its 14-story concentration mill, power plant, and company town infrastructure.

Five major mines including the Erie and Jumbo deposits fueled this massive operation.

The site’s stunning location between the Kennicott Glacier and Bonanza Mountain continues to attract visitors who can explore the preserved buildings and learn about the copper empire that helped power America’s industrial revolution.

The discovery began when two prospectors found a rich copper deposit containing 70% pure chalcocite in 1900, leading to the filing of the Bonanza Mine claim.

Rich Mining Heritage Lives

At the dawn of the 20th century, prospectors Clarence Warner and “Tarantula” Jack Smith stumbled upon an extraordinary copper deposit in Alaska’s rugged terrain, discovering ore with up to 85% purity.

The Alaska Syndicate transformed this discovery into America’s most ambitious copper extraction techniques, establishing the legendary Kennecott operation.

You’ll find this mining town nostalgia preserved in the fourteen-story concentration mill, standing ruby-red against the Alaskan wilderness.

From 1911 to 1938, the operation yielded 1.3 billion pounds of copper and 280 tons of silver, generating over $200 million in revenue.

Despite its closure during the Great Depression, Kennecott’s legacy endures.

The isolated community endured harsh winters with temperatures below -50°F while maintaining a self-sufficient lifestyle.

Today, as part of Wrangell-St. Elias National Park, the National Historic Landmark District showcases America’s pioneering spirit through preserved structures and innovative industrial heritage.

The site’s eeriness has earned it recognition as one of Alaska’s most haunted locations.

Remote Beauty Still Beckons

Since its closure in 1938, Kennecott’s remote location within Wrangell-St. Elias National Park has preserved its historical significance in near-pristine condition.

You’ll find this copper mining ghost town accessible only via unpaved road or small aircraft, situated 4 miles from McCarthy, Alaska.

The location was accurately documented through Wikipedia disambiguation pages to prevent confusion with similarly named places.

Your remote exploration will reveal a stunning backdrop of the Kennicott Glacier and snow-capped Wrangell Mountains, where nature has gradually reclaimed the industrial landscape.

As a National Historic Landmark District, Kennecott’s well-preserved mining structures offer you a rare glimpse into early 20th-century copper operations.

The site’s isolation limits visitor numbers, ensuring an authentic experience as you traverse the grounds.

During its peak operations, the town produced an astounding $200 million worth of copper ore.

While toxic mining remnants require ongoing monitoring, the surrounding wilderness provides exceptional opportunities for hiking, photography, and wildlife observation in one of America’s most isolated ghost towns.

Exploring abandoned towns in the American West can lead to fascinating discoveries of the region’s history and the stories left behind. The remnants of old buildings and forgotten artifacts tell tales of resilience and hardship faced by those who once called these places home. Each visit offers a glimpse into the past, inviting adventurers to reflect on the lives that once thrived in these now desolate landscapes.

St. Elmo’s Silver and Gold Heritage

The silver-rich mountains of Colorado birthed St. Elmo in 1878, when prospectors founded it as Forest City near the Mary Murphy Mine.

You’ll find this mining technology pioneer‘s legacy in the 220,000 ounces of gold and substantial silver yields extracted between 1870 and 1925, valued at $4.4 million.

St. Elmo’s history peaked when the Denver South Park & Pacific Railroad arrived in 1880, pushing the population to 2,000.

The arrival of the Denver South Park & Pacific Railroad transformed St. Elmo into a bustling frontier town of 2,000 souls.

The district’s 150 patented mine claims, including powerhouses like the Theresse C and Pioneer, shipped up to 75 tons of ore daily.

A remarkable 25-foot wide ore vein discovery in the Mary Murphy Mine sparked dreams of endless wealth.

Though mining ceased by 1925, St. Elmo’s preserved structures, including 40 original buildings, still tell tales of America’s mining frontier.

The town was renamed from Forest City after a romantic 19th-century novel by Griffith Evans.

Two devastating fires in 1890 and 1898 severely impacted the town’s prosperity and led to significant population losses.

Dearfield: The Dream of Black Pioneers

You’ll find Dearfield’s remarkable economic achievements reflected in its 1920s peak valuation of over one million dollars, when Black farmers mastered dry agriculture techniques to cultivate diverse crops in Colorado’s arid conditions.

The community’s vibrant social infrastructure, including a church, school, and the Dearfield Farmers Association, supported nearly 300 residents until the devastating combination of post-WWI market changes and the Great Depression triggered its decline.

Today, while most of Dearfield’s original structures have crumbled, preservation efforts through the Dearfield Dream Project work to protect this significant symbol of Black pioneering spirit and agricultural innovation.

Historical Black Economic Power

Founded in 1910 by visionary Oliver Toussaint Jackson, Dearfield emerged as Colorado’s sole all-Black agricultural settlement, encompassing 320 acres of townsite alongside 19,000 acres of farmland.

You’ll find evidence of remarkable economic empowerment in Dearfield’s peak years (1917-1921), when 300 residents established thriving enterprises including a concrete block factory, grocery store, and hotel, with the town’s value exceeding one million dollars.

The settlement’s cultural resilience shone through its cooperative ventures like the Dearfield Farmers Association, which united resources for modern equipment purchases.

Despite challenges of denied water rights and sandy soil, settlers mastered dry farming techniques, cultivating diverse crops from corn to watermelons.

They’ve proven their adaptability by trading with neighboring white farmers and creating a self-sufficient community complete with schools, churches, and social events.

Great Depression’s Fatal Impact

During Dearfield’s brief flourishing period in the late 1910s, few could’ve predicted the devastating chain of events that would soon unfold.

You’d have witnessed the first signs of economic decline in the mid-1920s when crop prices plummeted due to global market saturation. The agricultural collapse accelerated as nature dealt multiple blows: severe drought struck in the late 1920s, followed by the merciless Dust Bowl of the 1930s.

These environmental disasters coincided with the Great Depression, creating a perfect storm that devastated the once-thriving Black settlement. By 1936, you would’ve seen most families abandoning their dreams, unable to sustain their farms amid the harsh conditions.

The exodus left only O.T. Jackson and his niece by 1940, marking the end of this bold experiment in Black economic independence.

Community Life and Legacy

When Oliver Toussaint Jackson established Dearfield in 1910, his vision transcended mere agricultural settlement to create Colorado’s first self-sufficient Black farming community.

The community’s resilience manifested through innovative agricultural practices, including dry farming techniques and shared modern harvesting equipment.

You’ll find that Dearfield’s cultural legacy thrived through its four churches, bustling businesses, and vibrant social events like colony fairs and baseball games.

At its peak, 300 residents contributed to a community valued at over one million dollars.

Today, the Dearfield Dream Project spearheads preservation efforts, conducting research while working to transform the site into an educational center.

Though most original structures have vanished, Dearfield’s significance as a symbol of Black self-determination and economic independence endures.

Garnet’s Montana Mining Glory Days

The discovery of placer gold in Bear Creek during the mid-1860s marked the beginning of Garnet’s illustrious mining history, though the area wouldn’t reach its full potential until decades later.

You’ll find that early Garnet history centered on small-scale prospecting until the 1893 silver crash drove miners to seek gold instead.

Mining techniques evolved from simple placer operations to sophisticated lode mining, yielding an estimated $10 million in total gold production.

Calico’s Silver Mining Prosperity

Silver’s glittering promise beckoned prospectors to Calico Mountain on April 6, 1881, as John C. King and his fellow seekers struck it rich, establishing the legendary Silver King Mine.

You’ll find Calico’s heritage deeply rooted in this discovery, which sparked a remarkable silver boom that drew 3,000 residents to this Mojave Desert outpost.

Between 1881 and 1907, you’d have witnessed an astounding $13-20 million in silver extraction, with ore grades hitting $400-500 per ton.

The district’s infrastructure expanded rapidly, featuring a ten-mile narrow-gauge railroad and sophisticated stamp mills.

However, when silver prices plummeted from $1.31 to under 63 cents per ounce in the mid-1890s, Calico’s prosperity vanished.

Mormon Miners of Grafton, Utah

You’ll find Grafton’s origins tied directly to the Mormon pioneers who established this settlement in 1859 as part of Brigham Young’s Cotton Mission, rather than pursuing large-scale mining operations.

While skilled craftsmen and miners were present, Grafton’s Mormon community focused primarily on cooperative farming and irrigation projects until Native American conflicts and floods forced many to abandon the settlement by 1868.

Today, you can explore the well-preserved remnants of Mormon pioneer life, including the iconic 1886 adobe schoolhouse that served as the community’s religious and educational center.

Religious Settlement History

Founded in 1859 under Brigham Young’s direction, Grafton, Utah emerged as a distinctive Mormon pioneer settlement when five families ventured to establish a religious outpost along the Virgin River.

The Mormon migration demonstrated remarkable pioneer resilience as settlers implemented cooperative farming systems and built irrigation networks in the harsh desert landscape. You’ll find that these early settlers weren’t just farmers – they served as missionaries to the Southern Paiute people while creating a strategic corridor for church expansion.

The settlement’s religious purpose extended beyond mere colonization, as Jacob Hamblin worked extensively with local tribes.

However, mounting challenges, including floods and tribal conflicts, ultimately led to Grafton’s evacuation during the 1866 Black Hawk War.

Mormon Mining Operations

While Brigham Young initially discouraged precious metals mining to maintain the Mormon community’s agricultural focus, Mormon involvement in mining operations evolved markedly throughout the 1850s-1890s.

You’ll find their first significant mining venture in the 1850 “iron mission” near Cedar City, which aimed to reduce dependence on costly iron imports.

As railroad access expanded in the 1860s, you’d see Mormon leadership’s stance shifting toward lead and silver mining, particularly in Minersville.

After Young’s death, leaders like John Taylor and Joseph F. Smith acquired silver mine ownership in the 1880s-90s.

While settlements like Grafton remained primarily agricultural, they often served as support hubs for nearby mining operations, providing labor and supplies.

Mormon mining operations consistently prioritized community economics and self-sufficiency over individual profit-seeking ventures.

Surviving Pioneer Structures

Today, five primary pioneer structures stand as proof to Mormon settlement in Grafton, Utah, established in 1859 as part of the Cotton Mission.

The centerpiece of this ghost town preservation effort is the 1888 schoolhouse, constructed with a foundation of local lava rocks and adobe bricks made from clay found at the west end of town.

You’ll find pioneer architecture exemplified in the Russell home, built with traditional adobe techniques, and a surviving log cabin across from it.

The split-rail fence and cemetery with its wooden berry fence remain as evidence of the community’s resourcefulness.

The cemetery, dating from 1862 to 1924, features original headstones and marks the final resting place of settlers who braved floods and conflicts to establish this agricultural outpost.

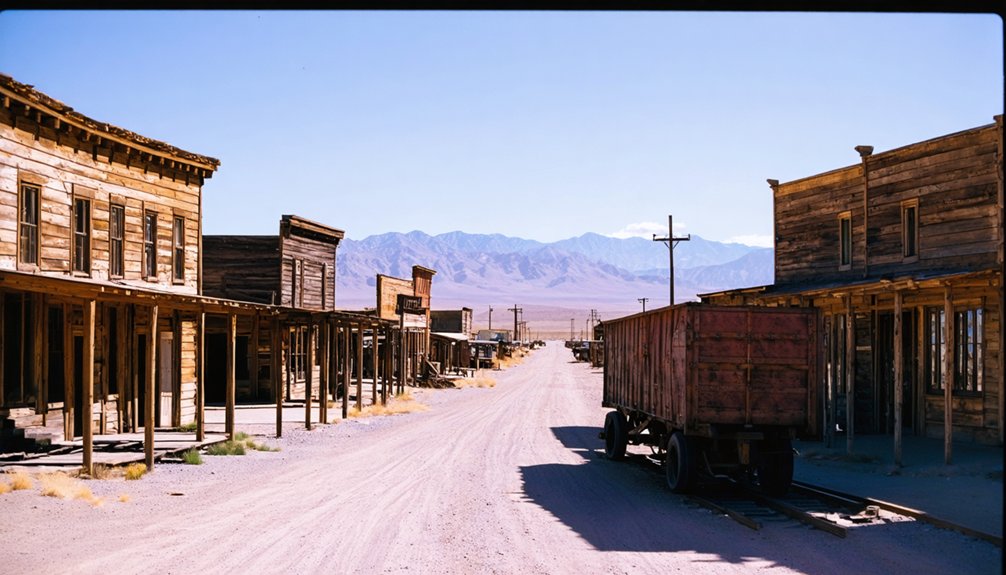

Steins: Where Railroad and Mining Met

In 1878, Southern Pacific Railroad initiated a transformative project by blasting through rock bluffs at Steins Pass, establishing what would become a significant transportation hub in New Mexico’s mining frontier.

You’ll find Steins’ history deeply intertwined with both railroad expansion and mining prosperity. The Southern Pacific’s arrival sparked rapid development, leading to:

- A thriving community of 1,000 residents by 1919

- A bustling commercial district with hotels, saloons, and bordellos

- A productive quarry supplying essential railroad ballast

- Important water deliveries by train at $1.00 per barrel

When the quarry closed in 1925, you could’ve witnessed the beginning of Steins’ decline.

The town’s fate was sealed when Southern Pacific discontinued its stop after World War II, and the post office closed in 1944, transforming this once-important hub into a ghost town.

Eckley’s Coal Mining Community

Four ambitious entrepreneurs transformed the humble shingletown of Eckley into a bustling coal mining community after discovering anthracite deposits on the Tench Coxe Estate in 1853. Operating under Sharpe, Leisenring and Company, they secured a 1,500-acre lease and rapidly developed mines and worker housing.

You’ll find this cultural heritage site retains its authentic 19th-century character, with rows of distinctive red and black wooden frame houses arranged along three main streets.

The community infrastructure included Protestant and Catholic churches, a company store, doctor’s office, and superintendent’s home. Irish immigrants initially filled unskilled mining positions, later advancing to better roles.

The town exemplifies how anthracite mining fueled America’s Industrial Revolution, while its preserved structures offer insights into the daily lives of miners and their families under company control.

Custer’s Idaho Mining Saga

Gold’s allure transformed the Yankee Fork area of central Idaho when prospectors struck deposits in 1867, leading to the establishment of Custer in 1878.

You’ll find Custer’s mining operations reached their zenith with the General Custer Mill, a 20-stamp steam-powered facility connected to the mine by a 3,200-foot aerial tram.

- The General Custer Mining Company, backed by George Hearst, built essential infrastructure including a toll road from Challis.

- Custer’s decline began in 1888 when the main mining company ceased operations, leaving only 34 voters by 1894.

- Lucky Boy Gold Mining Company revived operations in 1895, employing 130 men.

- Technology evolved through 1913 with cyanide tanks enhancing extraction efficiency.

Mining persisted sporadically until 1942, when World War II finally halted operations, leaving Custer to fade into ghost town status.

Frequently Asked Questions

How Did Mining Towns Handle Law Enforcement and Crime in Their Heyday?

You’d find law enforcement handled through vigilante justice, informal codes, and miners’ courts, later evolving to private police forces and formal systems for crime prevention as mining settlements matured.

What Happened to the Mining Equipment After These Towns Were Abandoned?

Mining machinery met multiple fates: you’ll find some was sold for scrap, others left to rust on-site. Equipment repurposing wasn’t common, though certain pieces remain preserved as historical artifacts today.

Did Any Former Residents Ever Return to Reclaim Their Abandoned Properties?

You’ll find documented cases of former residents attempting property reclamation, but success was rare due to unclear titles, high legal costs, and deteriorated infrastructure. Most return efforts occurred between 1950-1990.

How Did Children Receive Education in These Remote Mining Communities?

You’d have walked miles to tiny remote schools, where limited resources and isolation created unique education challenges. One-room schoolhouses taught multiple grades while adapting to mining town life’s harsh realities.

What Survival Techniques Did Miners Use During Harsh Winter Conditions?

You’ll need rigorous winter preparation: layering insulated clothing, maintaining cabin fires on green log bases, storing preserved food, and keeping survival gear like flint strikes ready for harsh conditions.

References

- https://whakestudios.com/us-ghost-towns/

- https://www.wisdomlib.org/science/journal/sustainability-journal-mdpi/d/doc1826618.html

- https://albiongould.com/ghost-towns-to-visit-in-the-states/

- https://www.generalkinematics.com/blog/5-old-abandoned-mining-towns/

- https://www.geotab.com/ghost-towns/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Abandoned_mine

- https://www.loveexploring.com/gallerylist/67994/americas-eeriest-gold-rush-ghost-towns

- https://www.science.gov/topicpages/a/abandoned+strip+mines

- https://devblog.batchgeo.com/ghost-towns/

- https://brucemctague.com/tag/abandoned-mines