You’ll find no visible traces of Anchor, South Dakota today, though this Black Hills mining settlement once buzzed with activity during the 1870s gold rush. Located in Lawrence County at 5,801 feet elevation, the town drew Northern European immigrants who built a vibrant community around gold mining operations. By 1967, Anchor had completely vanished, with all structures demolished. Yet beneath the natural landscape lies a fascinating story of frontier ambition, innovation, and ultimate decline.

Key Takeaways

- Anchor was established in the Black Hills during the 1870s gold rush at 5,801 feet elevation in Lawrence County.

- The town emerged around mining operations but declined when transportation patterns shifted from rail to truck transport.

- Complete demolition occurred in 1967, leaving minimal archaeological evidence and no visible structures at the former townsite.

- Mining operations included underground techniques, quartz crushing mills, and innovative equipment like heap leaching systems.

- The community consisted mainly of Northern European immigrants and featured a vital mail connection to Deadwood established in 1877.

The Rise of a Mining Settlement

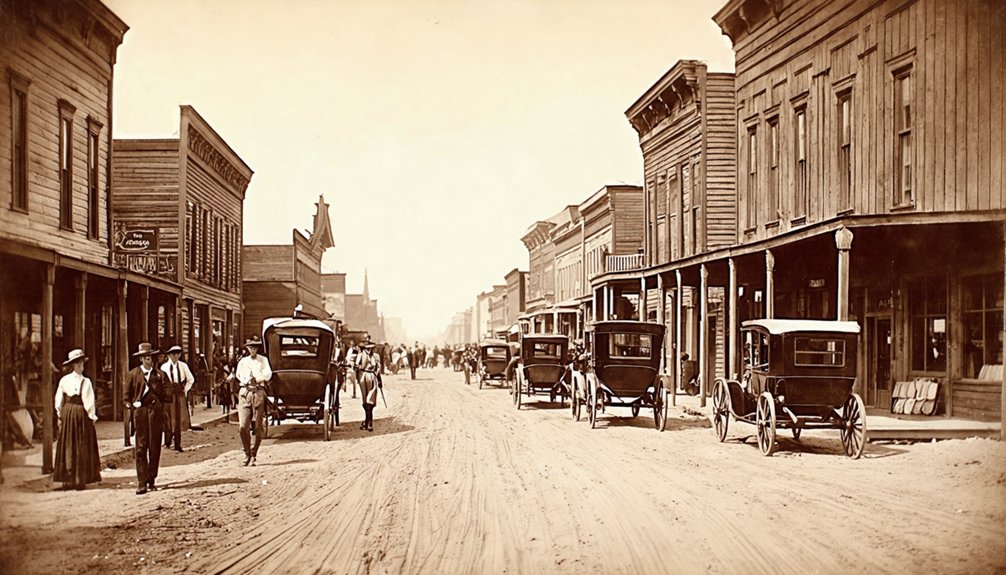

When gold and silver were discovered in South Dakota’s Black Hills during the 1870s, the mining settlement of Anchor quickly took shape at an elevation of 5,801 feet in Lawrence County.

Like Deadwood Gulch’s success, Anchor’s early placer mining operations quickly attracted thousands of fortune seekers to the area.

You’ll find that early prospectors were drawn to the area’s rich mineral veins, establishing underground operations that would define the region’s initial mining techniques. The settlement grew alongside other notable mines in the district, including Gilt Edge and Hoodoo, as miners sought their fortunes in the depths of Anchor Hill. The area would later become part of the Richmond Hill project, which focused on extracting near-surface oxide gold deposits.

While the early days saw traditional underground mining methods, you’d later witness a dramatic shift in the late 20th century when surface mining and heap leaching became prominent.

The evolution from underground tunnels to open-pit mining marked a significant transformation in how the Black Hills yielded their golden treasures.

This transformation brought new opportunities but also raised concerns about environmental impact that would shape the settlement’s future.

Life in Early Anchor

As Northern European immigrants settled in Anchor during the late 19th century, they formed a diverse yet tightly-knit community centered around religious institutions and farming life.

You’d find Danish, Finnish, and Dutch settlers working side by side, each bringing their cultural traditions to this frontier town. Settler experiences were marked by harsh winters and economic challenges, but they’d overcome these hurdles through cooperation and shared knowledge. The arrival of new rail lines in the region during the late 1870s helped connect these isolated farming communities to larger markets.

You could witness the heart of community life at places like the Singsaas Evangelical Lutheran Church, established in 1874, where families preserved their homeland languages while adapting to American life.

Daily routines revolved around farming, church activities, and education at the newly formed schools. Despite the hardships of frontier life, these determined immigrants built lasting social bonds through their shared religious faith and agricultural pursuits.

Mining Operations and Economic Growth

You’ll find Anchor’s mining legacy began with underground operations in the 1870s, when prospectors staked claims throughout the Northern Hills at elevations around 5,800 feet.

The early miners used quartz crushing mills and pulverizers to process gold and silver ore, marking some of the first mechanized mining attempts in the region. Records from the USGS indicate this was a small deposit operation, though its historical significance remains notable.

As operations expanded through the late 19th century, Anchor contributed to the broader economic boom that swept through Lawrence County, though specific production figures for the mine remain elusive. The area later incorporated heap leaching techniques which allowed for more efficient mineral extraction from the ore.

Early Mining Claims History

Three major developments marked the early mining claims in Anchor, South Dakota during the 1870s.

First, you’ll find at least 20 mineral claims were staked out, focusing on silver and gold extraction, with proper claim documentation filed through county and state authorities.

Next, the Anchor Mountain Mine emerged as a significant operation at 5,600 feet elevation in Lawrence County, establishing itself among the region’s premier gold mining locations.

Finally, the broader Union Hill area, including Anchor Hill, saw an influx of companies racing to secure their stakes under mining regulations.

These claims weren’t just paper transactions – they included patented acres surrounding the mines, giving private ownership rights to all minerals beneath the surface, ensuring long-term operational security for the claim holders.

Equipment and Production Methods

While primitive mining tools dominated Anchor’s earliest operations, the introduction of mechanized equipment in the late 1800s revolutionized production methods across South Dakota’s mining district.

You’d find miners upgrading from basic sledgehammers and mule-drawn arrastras to sophisticated mining technology like jaw crushers and massive 200-stamp mills such as the Golden Star.

The shift to 1½-ton trucks and Y4-yard shovels dramatically improved production efficiency in both underground and open-pit operations.

Later innovations included heap-leach technology for gold extraction and advanced water treatment processes using lime neutralization.

These improvements weren’t just about boosting output – they transformed how miners approached their work, balancing economic gains with environmental responsibilities through better waste handling and acid drainage management.

Peak Economic Growth Period

The modernization of mining equipment set the stage for Anchor’s most prosperous period during the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

San Francisco investors like George Hearst helped establish major mining operations in the region, setting precedents for future development patterns.

You’ll find that during this peak, the mine played a significant role in Lawrence County’s gold and silver production, contributing to South Dakota’s prominence among top U.S. gold-producing states.

The region’s economic diversification stemmed from mining operations that created jobs and supported ancillary businesses, similar to how the creation of 185 SURF jobs has revitalized the region’s economy today.

While specific production figures for Anchor Mine aren’t well-documented, it operated within a district that included the legendary Homestake Mine, which yielded over 40 million ounces of gold.

The community’s resilience became evident as mining activities evolved from traditional methods to open pit and heap leach techniques in the 1990s, adapting to changing economic and environmental demands.

Daily Challenges of Frontier Living

Living on South Dakota’s frontier demanded extraordinary resilience as settlers faced a relentless barrage of daily challenges.

You’d need frontier survival skills just to endure the brutal winters, where heavy snowfall could trap you in your crude cabin for weeks. Daily resourcefulness became essential as you’d battle constant food scarcity, often relying on preserved meats and whatever you could hunt or gather. You couldn’t count on regular supplies reaching your remote location, especially during harsh weather.

Brutal winters tested frontier survivors daily, forcing them to hunt, preserve food, and endure weeks trapped by relentless snow.

The isolation wore on you mentally, with limited communication to the outside world and no quick access to medical care if you got sick or injured. In 1877, the establishment of a mail line from Deadwood finally provided a vital connection to civilization. Many families ended up abandoning their homes, leaving behind ghost town remnants that still stand today.

Work never ended – you’d spend long hours performing backbreaking manual labor, knowing that one bad season or economic downturn could wipe out everything you’d built.

Notable Characters and Community Leaders

You’ll find Sarah “Aunt Sally” Campbell among Galena’s most remarkable pioneers, as this former slave became a successful rancher and the first non-Native woman in the Black Hills after working as a cook during Custer’s 1874 expedition.

Local leadership emerged from claim holders and business operators who maintained essential services like assay shops and supply stores for the growing mining community. The town experienced significant growth when railroad companies established routes nearby to transport goods and people.

While men dominated frontier politics, women like Campbell proved instrumental in shaping the social fabric through property ownership and community involvement, challenging the era’s gender norms.

Local Officials and Merchants

As mining operations flourished in Anchor, South Dakota, a small but influential group of officials and merchants emerged to shape the town’s development.

You’d find these early leaders wearing multiple hats – a postmaster might also serve as justice of the peace, while merchants didn’t just run their general stores but operated boarding houses and informal banks. Community governance often stemmed from mining company appointments rather than formal elections, with officials mediating disputes and managing claim access.

Merchant influence extended far beyond commerce, as store owners became vital community pillars by extending credit to miners, sponsoring local events, and coordinating with railroad companies.

Many eventually shifted into official leadership roles, combining their business acumen with civic duties to guide Anchor’s growth through its boom years.

Pioneer Women and Prospectors

Beyond the town’s established officials and merchants, Anchor’s pioneer women and prospectors shaped the early social fabric of this Black Hills settlement.

You’ll find their influence woven into every aspect of the community’s development, from the first rough-hewn cabins to the establishment of permanent homesteads.

- Sarah “Aunt Sally” Campbell blazed the trail as the first non-Native woman in the Black Hills, joining Custer’s 1874 Expedition before settling in nearby Galena.

- Prospectors discovered rich galena deposits in 1875-1876, shifting focus from gold to silver mining.

- James Conzette built a defensive cabin in 1876, though it never saw its intended use against raids.

- Pioneer women transformed mining camps into stable communities by running boarding houses, maintaining ranches, and establishing the area’s first permanent homes.

The Town’s Peak Years

During its heyday in the early 1900s, Anchor thrived as a bustling mining town with nearly 1,000 residents calling it home.

You’d have found a vibrant mix of families and bachelor miners, with community gatherings centered around the local boarding houses and mercantiles. The town boasted essential services including a post office, bank, and railroad connection, making it a regional hub in the Black Hills.

Life wasn’t just about mining – seasonal festivals and social activities brought townsfolk together at the two-room schoolhouse, which served about 25 students.

The infrastructure reflected Anchor’s permanence, with family cottages and converted buildings adapting to the community’s changing needs. Regular stagecoach service three times weekly kept you connected to neighboring settlements, while the railroad guaranteed steady commerce and passenger travel.

Signs of Decline

You’ll find the first signs of Anchor’s decline emerged through changing transportation patterns, as trucks gradually replaced the town’s essential rail connections for cattle transport and goods distribution.

The shift away from rail dependency hit Anchor particularly hard, with the post office and general store seeing dramatically reduced activity as neighboring towns grew more accessible by road.

The town’s isolation deepened when regular train service dwindled, triggering a steady exodus of residents and businesses that would continue until the devastating tornado of 2003 delivered the final blow.

Mining Operations Cease

While the Black Hills mining region once thrived with gold production, Anchor’s mining operations faced a series of devastating setbacks in the mid-1990s that ultimately led to their downfall.

You’ll find that strict mining regulations and growing concerns over environmental impacts created significant hurdles for the Anchor Hill operation.

- Dakota Mining Corporation struggled to secure Forest Service permissions, which severely delayed their start at Anchor Hill.

- Golden Reward mine halted operations in June 1996, entering a temporary cessation period.

- Acid rock drainage issues required extensive water treatment systems to protect Strawberry Creek.

- Plummeting gold prices, combined with mounting environmental costs, forced Brohm Mining Corporation into bankruptcy by 1999.

The area’s mining legacy ended with the site’s designation as an EPA Superfund location in 2000, requiring decades of ongoing environmental remediation.

Population Exodus Accelerates

Following the closure of mining operations, Anchor’s population decline mirrored the stark reality of Hyde County‘s broader exodus, where the number of residents plummeted by 53% since 1970.

You’ll notice the rural challenges became increasingly evident as household numbers dropped from 679 to 548, reflecting the harsh truth of families seeking opportunities elsewhere.

The population shifts hit particularly hard as younger residents left for urban areas, leaving behind an aging community with a median age of 46.1 years – considerably higher than South Dakota’s average of 36.9.

With more deaths than births and limited economic prospects, Anchor’s isolation proved too challenging for most to overcome.

The town’s story echoes a familiar pattern seen across rural counties with fewer than 5,000 residents, where 73% experienced similar losses.

Remnants and Ruins Today

Since the deliberate demolition of Anchor’s original structures in 1967, virtually no physical remnants of this South Dakota ghost town remain visible today.

Anchor ghost town’s complete 1967 demolition erased its physical presence, leaving South Dakota’s landscape bare of its historical structures.

If you’re planning a remnants exploration, you’ll find the site has largely reverted to natural landscape, unlike other regional ghost towns that still feature standing ruins.

- The cleared site contains few detectable foundations or footings, making archaeological findings extremely limited.

- You won’t find any preserved buildings or maintained structures, as the complete demolition contrasts with partially abandoned towns nearby.

- Ground surveys might reveal subtle land depressions or stone footings, but no recognizable building outlines exist above ground.

- The site lacks the typical ghost town features you’d expect, such as crumbling walls or roofless buildings, due to the thorough removal of all structures.

Historical Significance in the Black Hills

To understand Anchor’s place in Black Hills history, you’ll need to appreciate the profound transformation this region underwent during the late 1800s.

Before the gold rush forever altered these sacred lands, the Black Hills were home to numerous Indigenous peoples, particularly the Lakota who called it Ȟe Sápa.

When gold was discovered in 1874, the area’s character changed dramatically, leading to broken treaties and forced relocation of Native Americans.

Anchor emerged as one of many mining settlements that dotted the Black Hills during this pivotal era.

The economic impacts rippled far beyond the 41 million ounces of gold extracted over 126 years – you can still see evidence of this mining heritage in the remaining structures and sites that tell the complex story of industrial ambition colliding with Indigenous heritage.

Preserving Anchor’s Legacy

While many ghost towns fade into obscurity, Anchor’s legacy lives on through dedicated preservation efforts that span multiple fronts. Through community preservation initiatives, you’ll find a rich tapestry of cultural heritage being safeguarded for future generations.

Ghost towns may vanish, but Anchor endures through passionate preservation work that keeps its cultural heritage alive for tomorrow’s generations.

- You can participate in guided town walks and storytelling events organized by local historical societies, connecting directly with Anchor’s past through firsthand accounts and expert narration.

- The South Dakota State Historic Preservation Office helps protect Anchor’s remains through legal measures and funding opportunities.

- Documentary films and academic research projects capture the town’s history, with students and historians working to record oral histories from descendants.

- You’ll discover ongoing volunteer opportunities that let you contribute to physical preservation tasks while joining a community dedicated to protecting Black Hills heritage.

Frequently Asked Questions

How Did Anchor’s Location Compare to Other Black Hills Ghost Towns?

You’ll find Anchor was more remote than tourist-friendly ghost towns, impacting its economic survival. Its historical significance faded as it couldn’t adapt like other Black Hills settlements near major transportation routes.

Were There Any Significant Conflicts Between Miners and Native Americans in Anchor?

While direct records don’t show specific mining disputes at Anchor itself, you’ll find it was part of broader cultural clashes where Lakota warriors actively resisted illegal mining throughout the Black Hills.

What Happened to the Mining Equipment After the Town Was Abandoned?

You’ll find most mining equipment was left to deteriorate in place due to removal costs, though some was salvaged or shared between companies, like Anchor’s compressor plant that Oreano Mining Company later used.

Did Any Natural Disasters Contribute to Anchor’s Eventual Abandonment?

Like footprints in shifting sand, you won’t find any records of natural disasters causing Anchor’s demise. The town’s spirit faded solely from economic decline and depleted mining resources.

Are There Any Surviving Photographs or Maps of Anchor’s Original Layout?

You won’t find publicly available historical documentation or visual evidence of Anchor’s layout, though you might discover hidden treasures in state archives or private collections that haven’t been cataloged.

References

- https://www.legendsofamerica.com/galena-south-dakota/

- https://www.powderhouselodge.com/black-hills-attractions/fun-attractions/ghost-towns-of-western-south-dakota/

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Glucs_Rq8Xs

- https://www.sdhspress.com/journal/south-dakota-history-2-2/some-black-hills-ghost-towns-and-their-origins/vol-02-no-2-some-black-hills-ghost-towns-and-their-origins.pdf

- https://www.sdpb.org/rural-life-and-history/2023-08-21/some-black-hills-ghost-towns-and-their-origins

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_0WNYsFLSLA

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_ghost_towns_in_South_Dakota

- https://icatchshadows.com/okaton-and-cottonwood-a-photographic-visit-to-two-south-dakota-ghost-towns/

- https://www.onlyinyourstate.com/experiences/south-dakota/capa-ghost-town-sd

- https://danr.sd.gov/Environment/MineralsMining/MiningHistory.aspx