You’ll find Aravaipa ghost town tucked away in Graham County, Arizona, where three distinct mining surges between the 1870s and 1920s shaped its development. The town supported lead, zinc, and copper mining operations, boasting over 30 buildings at its peak, including dormitories and a post office. Today, the well-preserved stone superintendent’s residence and scattered ruins stand as silent witnesses to this once-bustling mining community, while countless stories of Native peoples, settlers, and miners linger in the surrounding wilderness.

Key Takeaways

- Aravaipa was a mining town established in the 1870s, primarily focused on lead and zinc extraction before transitioning to copper operations.

- The town featured over 30 buildings during its peak, including dormitories, a post office, and a well-preserved stone superintendent’s residence.

- Mining operations declined sharply after 1921, with a failed revival attempt in 1926-1927, leading to the town’s abandonment.

- Population dwindled from 17 residents in 1900 to 12 by 1920, with the post office closure in 1893 marking early decline.

- Today, stone foundations, partial walls, and mining equipment ruins remain as testament to Aravaipa’s mining heritage.

The Birth of a Mining Frontier

Three distinct mining surges shaped Aravaipa’s early development as a mining frontier in Arizona. The first wave began in the 1870s when prospectors filed initial mining claims, marking the region’s entry into Arizona’s mineral rush.

You’ll find that early prospecting techniques remained basic, with miners focusing on lead, zinc, and minor copper deposits using manual extraction methods. This period coincided with the General Mining Act which opened up vast territories for mineral exploitation.

The frontier character of Aravaipa becomes clear when you examine the sporadic nature of early development. While prospectors scoured the area throughout the late 1800s, they established no major operations. The Aravaipa Mining Company transformed the area in the 1890s by constructing eight buildings including dormitories and a post office.

Instead, you’d have seen small-scale workings scattered across the district, with minimal infrastructure and temporary camps. The modest ore shipments of this period reflect the challenges miners faced in this remote location.

Native Peoples and Early Settlement

Long before Aravaipa became a mining town, you’d find prehistoric Salado, Mogollon, and Hohokam peoples cultivating crops along Aravaipa Creek’s fertile banks.

The Aravaipa Apache later claimed this territory as their homeland, combining seasonal farming with hunting and gathering while fiercely defending their independence against Spanish colonizers. Despite ongoing conflicts, they established themselves as important trading partners, providing corn and melons to nearby settler communities.

You’ll find that this resistance to outside encroachment ultimately culminated in the tragic Camp Grant Massacre of 1871, where 144 Apache people, mostly women and children, were killed by a coalition of Anglo Americans, Mexican Americans, and Tohono O’odham. The incident sparked intense national debate over the treatment of Native Americans in the borderlands.

Ancient Indigenous Communities

Before Spanish explorers set foot in the region, the valleys of Aravaipa and San Pedro were home to thriving agricultural societies that built extensive villages along the waterways approximately 1,000 years ago.

These prehistoric agriculture settlements flourished in the riparian zones, where indigenous cultures like the Salado, Mogollon, and Hohokam established their presence. By the time Coronado explored in 1540, most of these villages had been abandoned.

The Aravaipa Apache would later make this area their home until the Camp Grant Massacre decimated their community in 1871.

You’ll discover evidence of their sophisticated lifestyle through:

- Advanced farming practices that took advantage of the fertile valley soils

- Strategic village locations that provided access to both hunting grounds and croplands

- Complex territorial networks that served as frontiers against rival groups

Apache Territory Conflicts

After the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo in 1848, mounting tensions between Apache tribes and white settlers erupted into a devastating 25-year conflict known as the Apache Wars.

Both the Union and Confederate forces sought to remove Apache peoples from their ancestral territories during the American Civil War. You’ll find that Apache resistance intensified following the Bascom Affair in 1861, when U.S. forces wrongly executed Chief Cochise‘s relatives. Leaders like Cochise, Mangas Coloradas, and Geronimo fought to protect their ancestral lands using guerrilla tactics and intimate knowledge of the rugged terrain.

Military strategies from both sides shaped the conflict’s progression. While the U.S. Army established forts like Fort Bowie to control water sources and protect settlers, Apache warriors conducted strategic raids and ambushes to offset their numerical disadvantage. The conflict finally ended when General Nelson Miles captured Geronimo in 1886.

The Battle of Apache Pass in 1862 highlighted this dynamic, as artillery proved decisive against Apache forces defending this vital territory.

The Copper Mining Heyday

Copper mining activity in Aravaipa emerged in the late 1870s, with early operations at the Friend, Stanley, Copper Reef, and Princess Pat mines marking the district’s beginnings.

You’ll find that the most significant development occurred between 1903 and 1918, when lessees and small operators extracted ore and shipped it to El Paso smelters via the Glenbar railroad station. The completion of the Southern Pacific Railroad in 1876 had made such copper mining operations economically viable throughout Arizona.

The district’s production peaked during this period but declined sharply after 1921, with a brief revival attempt through a flotation concentrator in 1926 that failed by 1927. The mine site, situated at 4,600 feet elevation, remains a testament to Arizona’s rich mining heritage.

Mining Operations Begin

Mining activity surged in Aravaipa during the late 1800s, marked by the construction of a small smelter near the claims in 1878.

You’ll find that early operations focused on extracting lead, zinc, copper, and silver, with mining equipment primarily servicing underground operations.

Raw ore transportation initially went to Glenbar station, about 40 miles north, before heading to El Paso for smelting.

- The Light Mine began production in 1903, receiving its patent by 1907

- The Princess Pat Copper Mining Company acquired both the Butte & Arizona and Palo Alto groups

- The Friend, Stanley, Copper Reef, and Princess Pat mines operated until 1918-1919

Equipment and Infrastructure Development

During the copper mining heyday, Aravaipa’s landscape transformed with an array of specialized equipment and facilities supporting extraction operations.

You’d have seen mining technology evolve from basic hand tools to steam-powered hoists and mechanical drills, while explosives like black powder and dynamite helped break through tough rock faces. Narrow-gauge rail lines replaced horse-drawn wagons, increasing ore transport efficiency.

Infrastructure challenges in this remote terrain didn’t stop determined miners from establishing essential facilities. They built shaft houses, stamp mills, and smelters near their claims, while constructing crucial water management systems to support processing in the arid environment.

Small settlements sprouted up, complete with housing, supply stores, and communal buildings – though limited infrastructure and difficult ore grades ultimately kept operations modest compared to larger Arizona districts.

Production Peak and Decline

As the calendar turned to the late 1870s, Aravaipa’s mineral wealth began drawing prospectors and miners to its rugged terrain.

While early operations remained small-scale, by 1907 significant claim patenting sparked a surge in mining activity. You’d find several notable operations, including the Friend, Stanley, and Grand Reef mines, shipping ore to distant smelters.

Mining challenges plagued the district’s potential:

- Hauling raw ore 40 miles to Glenbar’s railroad station drove up costs

- The flotation concentrator’s inability to properly separate zinc from lead hurt profits

- Wet conditions in mines caused equipment deterioration

These economic factors, combined with processing inefficiencies and market fluctuations, led to Aravaipa’s decline.

Life in the Aravaipa Valley

Life along Aravaipa Creek flourished for centuries before modern settlement, starting with the prehistoric Hohokam, Mogollon, and Salado peoples who established thriving communities in the valley.

Ancient cultures like the Hohokam, Mogollon, and Salado created vibrant communities along Aravaipa Creek’s life-giving waters.

The creek’s reliable water supply sustained valley agriculture and created a rich Aravaipa ecology that supported diverse human activities.

The Aravaipa Apache later adopted a semi-nomadic lifestyle here, planting crops in spring and harvesting in summer while moving between canyon and valley locations.

They’d gather for ceremonies tied to seasonal cycles, maintaining strong clan structures under chiefs like Ezkiminzin and Capitan Chiquito.

This traditional way of life changed dramatically with the arrival of Spanish, Mexican, and Anglo-American settlers, who established farms and ranches.

The newcomers’ presence led to increased conflict, ultimately disrupting the indigenous communities that had called the valley home for generations.

Architecture and Infrastructure

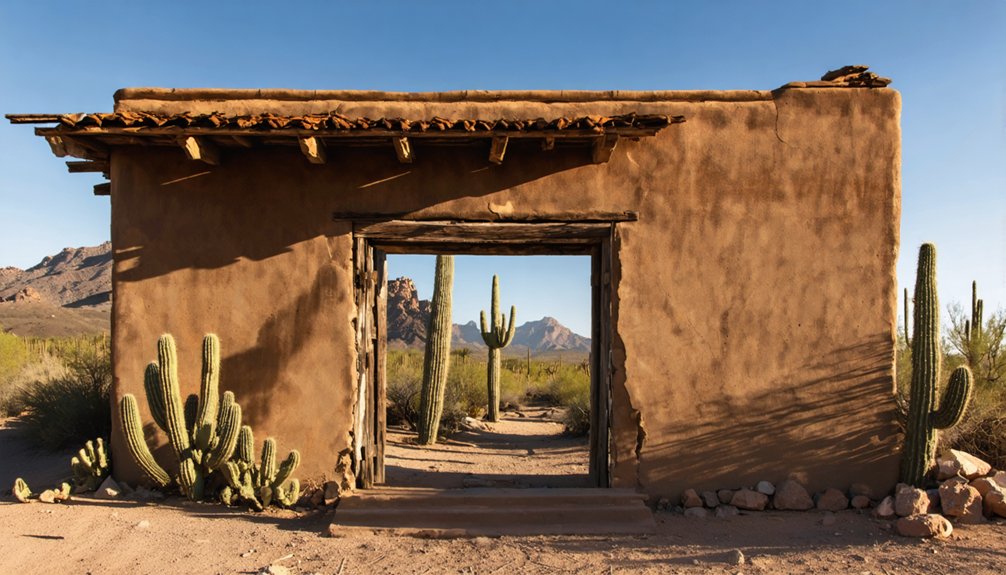

The late nineteenth century saw Aravaipa transform from an indigenous settlement into a bustling mining town, with its architecture reflecting the practical needs of its new inhabitants.

The town’s infrastructure legacy includes remnants of over 30 buildings that once supported lead and zinc mining operations. You’ll find the town architecture was primarily utilitarian, featuring simple construction techniques and local materials.

Key features of Aravaipa’s built environment included:

- Mining dormitories, a dining hall, and specialized ore processing facilities

- Essential services like a post office (1883-1893), schoolhouse, and pool hall

- Transportation infrastructure with dirt roads connecting mines through natural washes

Today, you can explore building foundations, partial walls, and scattered ruins that tell the story of this once-thriving mining community, though access now requires 4WD vehicles in certain areas.

The Camp Grant Connection

Located just downstream from Aravaipa, Camp Grant served as an essential U.S. military outpost where Lieutenant Royal Emerson Whitman established a refuge for nearly 500 Aravaipa and Pinal Apaches in early 1871.

Under Whitman’s supervision, you’d have found the Apache people engaging in agricultural activities, including cutting hay and harvesting barley near settlers’ fields.

The Apache Refuge‘s existence was tragically cut short on April 30, 1871, when a vigilante group of about 150 people attacked the camp, killing approximately 120 Apache women, children, and elderly while the men were away hunting.

Following this devastating massacre, the military relocated Camp Grant near Mount Graham in 1873, and surviving Apache people were moved to the San Carlos Reservation, forever changing the region’s cultural landscape.

Natural Surroundings and Geography

Nestled between Tucson and Phoenix in southeastern Arizona, Aravaipa’s ghost town sits within a striking wilderness area spanning 19,410 acres of rugged canyon terrain.

You’ll find yourself in a unique ecosystem where the year-round flowing Aravaipa Creek carves through towering cliffs, creating an essential water source that supports incredible wildlife diversity amid the desert landscape.

- The western foothills of the Santa Teresa Mountains rise around the ghost town, featuring rocky outcrops and mature juniper trees.

- Perennial creek waters form natural pools throughout the canyon, requiring multiple crossings as you explore.

- Seasonal changes transform the area’s character, from hot summers to mild winters, affecting both flora and fauna patterns.

The varied topography ranges from sandy creek banks to steep cliff walls, making this remote wilderness a reflection of nature’s raw beauty.

Decline of a Boom Town

While Aravaipa’s mining operations initially sparked hope and development in the 1870s, the town’s prosperity proved short-lived as declining ore quality and falling commodity prices took their toll.

Hope bloomed briefly in 1870s Aravaipa, but poor ore and falling prices soon withered the mining town’s dreams.

You’ll find evidence of this mining legacy in the population numbers, which dropped from 17 residents in 1900 to just 12 by 1920.

The economic transformation hit hard and fast. The post office’s closure in 1893 marked the beginning of the end, followed by the shutdown of major mines and exodus of mining companies.

As businesses and social venues closed their doors, residents moved away seeking better opportunities. The town’s infrastructure crumbled, leaving only a few abandoned structures, including the superintendent’s residence, as silent witnesses to Aravaipa’s brief moment of prosperity.

Preserved Structures Today

Today you’ll find the stone superintendent’s house, once home to Harry Firth, standing as the best-preserved structure in Aravaipa’s ghost town landscape.

While most of the town’s original buildings have crumbled into foundations and scattered rubble, the Firth residence maintains much of its 1890s exterior appearance, though it may have merged with an adjacent building in the 1940s.

The mining site still features its inclined shaft, headframe, and rusted hoist machinery, with a cable system that has remained largely unchanged since the 1990s.

Stone Superintendent’s House

The Stone Superintendent’s House stands as one of Aravaipa’s most remarkable preserved structures, dating back to its 1890s construction by the Aravaipa Mining Company.

Originally home to Harry Firth, the superintendent’s role involved overseeing the bustling mining operations from this strategic location. The architectural significance of this two-story stone building has proven invaluable, as it’s recognized as one of Arizona’s best-preserved territorial-period structures.

You’ll find these distinctive features:

- Original stone exterior walls that have withstood time while wooden structures disappeared

- Historic placement next to other 1890s buildings, showcasing the mining camp’s original layout

- Evidence of 1940s adaptation when it was integrated into an adjacent structure

The house remains a symbol of the social hierarchy and operational management of Arizona’s mining era, maintaining much of its original appearance.

Mining Equipment Remnants

Beyond the stone superintendent’s house, significant mining equipment remnants dot Aravaipa’s landscape, offering glimpses into its industrial past.

You’ll find the main hoist structure with its cable and headframe still standing, though weathered. The historical significance of these remnants is evident in the rusted mining machinery within the inclined shafts, once essential for extracting lead and zinc ore.

While most steam boilers have been salvaged by locals for repurposing, one disassembled boiler shell remains near the townsite.

Time and nature have begun reclaiming these industrial relics, with mature juniper trees growing among the equipment sites.

Partial walls and foundations of equipment enclosures survive, telling the story of Aravaipa’s changeover from steam power to gasoline, diesel, and electric mining operations.

Original Building Foundations

Standing as the most prominent survivor of Aravaipa’s mining era, the stone superintendent’s residence built by Harry Firth remains remarkably preserved among scattered building foundations throughout the townsite.

Foundation analysis reveals the original footprint of over 30 structures that once comprised this bustling mining community, though today you’ll find mostly stone outlines and partial walls marking where buildings once stood.

- You can trace the foundations of former dormitories and the dining hall, which showcase locally quarried stone and mortar construction.

- The structural remnants indicate a typical late-1800s mining camp layout, with utilitarian design and minimal ornamentation.

- You’ll notice juniper trees growing near many foundations, marking decades of abandonment since the town’s mid-20th century decline.

Legacy in the Arizona Wilderness

While many Arizona ghost towns have vanished entirely, Aravaipa’s stone structures and mining remnants continue to mark its presence in Graham County’s rugged wilderness.

At 4,600 feet elevation in the Santa Teresa Mountains’ western foothills, you’ll find Harry Firth’s superintendent’s residence standing as a symbol of the town’s cultural significance.

The landscape preserves the stories of lead and zinc mining operations from the 1890s, with rusted hoists and building foundations still visible along Arizona Gulch.

Today, environmental preservation efforts protect the surrounding wilderness where Aravaipa Creek flows.

You can trace the town’s evolution from Burt Dunlap’s 1882 ranch headquarters to its mining heyday, marked by two-story structures that were uncommon in territorial Arizona settlements.

Frequently Asked Questions

Are There Any Paranormal Activities Reported in Aravaipa’s Abandoned Buildings?

You won’t find any documented ghost sightings or paranormal activities in Aravaipa’s buildings. Unlike other haunted locations in Arizona, there’s no credible evidence of supernatural occurrences in this remote ghost town.

What Happened to Harry Firth’s Descendants After Leaving Aravaipa?

Like many frontier families seeking better opportunities, Firth’s descendants dispersed from Aravaipa during economic decline. Records don’t track their exact fate, though the Firth legacy lives on through their ancestor’s stone residence.

Can Visitors Legally Collect Artifacts From the Aravaipa Ghost Town Site?

No, you can’t legally collect artifacts – it’s a felony under federal legal regulations. You’ll face up to $100,000 in fines and 10 years imprisonment for violating artifact preservation laws.

What Was the Average Wage of Miners Working in Aravaipa?

While you’re keen to know historical miner wages, exact figures aren’t documented for Aravaipa’s peak period (1903-1921). You can assume miners earned modest daily wages, similar to other small Arizona mining operations.

Did Any Famous Outlaws or Gunfighters Ever Visit Aravaipa?

You won’t find any famous outlaws in Aravaipa’s history – the small mining town’s modest size and limited activity didn’t attract notorious gunfighters, with violence mainly tied to Apache conflicts elsewhere.

References

- http://www.azbackcountryadventures.com/arav.htm

- https://southernarizonaguide.com/camp-grant-massacre-part-circumstances-leading-slaughter/

- http://www.azheritagewaters.nau.edu/loc_aravaipa_creek.html

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aravaipa

- https://kids.kiddle.co/Aravaipa

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gGQOV4TdXFo

- https://www.ghosttowns.com/states/az/aravaipa.html

- https://pubs.usgs.gov/bul/0763/report.pdf

- https://haulno.com/canyon-mine-grand-canyon-colonialism-timeline/

- https://winfirst.wixsite.com/arizonamininghistory/history