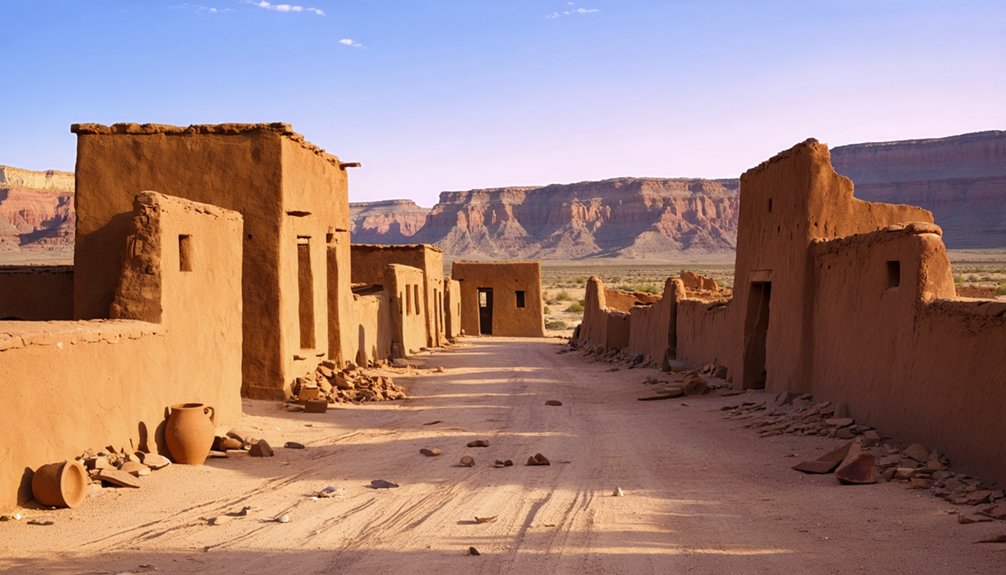

You’ll find Adamana along the old Santa Fe Railroad line in northeastern Arizona, where it served as the primary gateway to Petrified Forest National Park. Established in 1896 and named after rancher Adam Hanna, this once-bustling stop featured Campbell’s Hotel, which housed tourists and adventurers until 1965. The town’s decline began with Interstate 40’s construction, which bypassed the settlement. The abandoned buildings and rail ruins tell fascinating tales of Arizona’s railroad era.

Key Takeaways

- Adamana was established in 1896 as a railroad town named after rancher Adam Hanna, serving as the gateway to Petrified Forest National Park.

- Chester Campbell’s Hotel provided lodging for tourists visiting the Petrified Forest until its destruction by fire in 1965.

- The town’s decline began with the construction of Interstate 40, which diverted traffic away from the settlement.

- The post office closure in 1969 marked Adamana’s final transformation into a ghost town, ending its role as a community hub.

- Preservation efforts focus on protecting remaining structures and documenting the town’s history through family records and historical documentation.

The Origins of Adamana’s Name

While many Arizona towns bear the names of mining claims or geographic features, Adamana’s origins trace back to a simple rancher’s homestead. You’ll find its roots in the name “Adam Hanna’s,” established in 1896 after a prominent local rancher who owned land in the area. This ranching influence shaped the early identity of the settlement. The Santa Fe Railroad purchased the Atlanta & Pacific Railroad line in 1897, cementing the town’s importance as a transit point.

The name evolution from “Adam Hanna’s” to “Adamana” occurred naturally as more travelers passed through, particularly after the Santa Fe Railroad made it a key stop in 1897.

You’ll notice this simplified version became standardized on railroad timetables and signage. The transformation reflected a common pattern in the American Southwest, where lengthy descriptive names were shortened for practical use while maintaining their connection to early settlers. The town later gained prominence as a gateway to Petrified Forest when the area received national park status in 1906.

Life Along the Santa Fe Railroad

The arrival of the Santa Fe Railroad in 1897 transformed Adam Hanna’s modest settlement into a bustling rail stop. You’d have found a vibrant mix of railroad workers, their families, and travelers passing through, all living life by the rhythm of train whistles.

The depot served as more than just a station – it was your post office, telegraph hub, and community gathering spot. This location became one of several important Santa Fe Depot stops that anchored communities across the American Southwest.

Small-town depots were the heartbeat of frontier communities, where mail, messages, and memories intertwined under one roof.

Railroad expansion brought unprecedented opportunities to this remote outpost. You could find work laying track, maintaining locomotives, or handling freight, though the jobs weren’t without their risks. Tensions sometimes arose when competing rail crews fought over strategic routes through the territory.

The economic diversification that followed brought new markets for cattle, minerals, and timber. Where once you’d face isolation, the rails now connected you to Phoenix, Prescott, and beyond, making Adamana an integral part of Arizona’s growing rail network.

Gateway to the Petrified Forest

Since its establishment in 1896, Adamana served as the primary gateway to what would become Petrified Forest National Park, offering rail travelers their first glimpse of Arizona’s ancient treasures.

Originally named “Adam Hanna’s” after a local rancher, the settlement’s Santa Fe Railroad station became the jumping-off point for tourist experiences in the surrounding 2,000-acre wonderland.

The Fred Harvey Company published postcards and promotional materials showcasing the area’s natural wonders to potential visitors.

You’d find early visitors exploring vast stretches of petrified logs by horseback, marveling at specimens up to ten feet in diameter scattered across water-worn basins and gulches.

The natural beauty extended beyond fossilized wood to include Native American petroglyphs and sweeping desert vistas. Located at 5,400 feet elevation, the town provided visitors a comfortable base to explore the region’s prehistoric treasures.

While modern highways eventually bypassed Adamana, diminishing its role as the park’s entrance, the town’s legacy lives on as the historic doorway to one of America’s most unique landscapes.

Campbell’s Hotel and Tourism Heyday

If you’d traveled through Adamana in the early 1900s, you would’ve found Chester Campbell’s Hotel serving as the primary lodging for Petrified Forest visitors, offering rooms for 15 guests and meals for up to 30 people.

The hotel’s strategic location at the Santa Fe Railway stop made it a natural gateway for Eastern tourists exploring the area’s prehistoric wonders.

Campbell organized guided tours through both the Painted Desert and Petrified Forest, helping visitors discover the area’s unique geological features.

The town’s significance eventually faded when the post office closed in 1969, marking the end of an era.

Early Tourist Accommodations

Located near the entrance to Petrified Forest National Park, Campbell’s Hotel emerged in the early 1900s as Adamana’s premier tourist accommodation under Chester B. Campbell’s management.

Much like the tourist interest in Alaska that predated the Klondike Gold Rush, Adamana’s hospitality sector grew to meet increasing visitor demand.

As a cornerstone of early hospitality in the region, the hotel could house fifteen guests and serve meals to thirty people at once. You’d have paid $2.50 for daily board and lodging, enjoying modern amenities like sanitary plumbing – quite a luxury for the time. Like Judge C.C. Campbell’s establishment in Lake Chelan, the hotel became known for its legendary hospitality service.

The tourist infrastructure included a livery service offering coaches for up to 40 people, making excursions to various petrified forests possible. From the hotel, you could book guided tours to different forest sections, petroglyphs, and scenic desert vistas, with rates of $4.00 for singles or $2.50 per person in groups.

Railroad Stop Prominence

The Santa Fe Railroad‘s decision to establish Adamana as a whistlestop in 1897 transformed this small desert outpost into a bustling gateway for Petrified Forest tourism.

You’d find yourself joining countless other adventurers disembarking from special excursion trains, ready to explore the ancient petrified trees just a mile away in open-topped Harvey Cars.

The railroad significance of Adamana centered around Campbell’s Hotel, where you could rest and gather information before your forest expedition.

The tourism evolution was in full swing by 1908, with the Santa Fe Railway actively promoting these unique desert excursions in their brochures.

But as automobiles gained popularity and roads improved, you’d have witnessed Adamana’s gradual decline.

Travelers began bypassing the whistlestop entirely, driving straight to the Petrified Forest instead.

Peak Visitor Years

During peak tourism years between 1900-1920, Campbell’s Hotel served as Adamana’s hospitality cornerstone, welcoming rail travelers enthusiastic to explore the Petrified Forest’s ancient wonders.

Visitor demographics centered on rail passengers who’d pay $2.50 per day for lodging and meals at the hotel, which could accommodate up to 30 guests at a time. By 1917, you’d find modern amenities like hot and cold running water with sanitary plumbing.

Tourism trends showed increasing interest in guided excursions to various forest sections. For $4.00, you could join round-trip tours to the First, Second, Third, Blue, and North Sigillaria Forests.

Al Stevenson’s livery service transported up to 40 visitors daily, while local guide James Donohue led explorations of petroglyphs and prehistoric ruins for an additional fee.

Daily Life in a Desert Railroad Town

Living in Adamana during its heyday meant adapting to the rhythms of the Santa Fe Railroad, which served as the town’s lifeline and economic engine.

You’d start your daily routines watching freight and passenger trains roll through, bringing supplies, tourists, and connections to the outside world. Children walked along the tracks to reach their one-room schoolhouse, where a single teacher educated about a dozen students of different grades.

Community gatherings revolved around the Campbell Hotel and trading post, where you’d find ranchers, railroad workers, and tourists mingling.

The Campbell Hotel served as Adamana’s heart, where locals and travelers alike shared stories over coffee and supplies.

You’d make your living through ranching, working the railroad, or catering to visitors heading to the Petrified Forest. Life wasn’t fancy – no paved roads or modern amenities – but the close-knit desert community of roughly 180 residents looked after one another.

Native American Heritage and Artifacts

Long before Adamana’s railroad days, Paleoindians first settled this region around 13,500 BC, establishing a rich Native American heritage that would span millennia.

As you explore the area today, you’ll find remnants of the Ancestral Puebloans who called this land home, leaving behind native artifacts that tell their fascinating story.

- Adamana Brown pottery, some of northern Arizona’s earliest ceramics, reveals the sophistication of Basketmaker settlements.

- Multi-story pueblos and kivas showcase advanced architectural skills using local petrified wood.

- Distinctive Black-on-Red and polychrome pottery styles connect this area to other regional settlements.

- Petroglyphs and solar markers throughout the Little Colorado River Valley demonstrate astronomical knowledge.

- Tools crafted from petrified wood and obsidian highlight resourceful adaptation to the desert environment.

The Path to Abandonment

Although Adamana began promisingly in 1896 as an essential railroad stop serving Petrified Forest National Park visitors, its path to abandonment unfolded through a series of economic and infrastructural shifts.

You can trace the abandonment causes to several key events: the gas plant’s relocation across the tracks reduced local jobs, while Campbell’s Hotel’s destruction by fire in 1965 eliminated vital visitor lodging.

The most devastating blow came when Interstate 40’s construction bypassed the town entirely, cutting off the steady flow of travelers that had sustained local businesses.

These economic shifts triggered a mass exodus, and by the late 1960s, even the post office had closed.

With no permanent residents remaining, Adamana’s buildings fell into decay, leaving only scattered ruins as evidence of its brief existence.

Preserving Adamana’s Story

Despite its physical decline, Adamana’s story endures through a rich tapestry of historical documentation and preservation efforts.

You’ll find its legacy preserved through early 20th-century family records, oral histories, and archival materials from the Aztec Land & Cattle Company. Community engagement remains strong, with descendants of early settlers actively sharing stories and photographs that bring the ghost town’s past to life.

- Campbell’s Hotel ruins stand as a tangible reminder of Adamana’s heyday

- Historical societies feature exhibits highlighting the town’s significance

- Family histories continue to uncover new details about early residents

- Travel guides and interpretive signage help visitors explore the site

- Local newspapers from the 1900s document Adamana’s role as a tourist gateway

Historical preservation efforts focus on stabilizing remaining structures while monitoring the site for vandalism, ensuring future generations can connect with this piece of Arizona’s past.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can Visitors Still Access the Original Buildings and Structures in Adamana Today?

You can’t access original buildings in Adamana today due to minimal historical preservation efforts. Most structures have vanished, leaving only a desolate site dominated by a natural gas plant.

What Natural Disasters or Extreme Weather Events Has Adamana Experienced?

You’ll find Adamana’s history marked by devastating flood damage from storms like 1970’s Tropical Storm Norma, plus ongoing drought effects that’ve shaped the landscape through flash floods, dust storms, and extreme heat.

Were Any Movies or Television Shows Ever Filmed in Adamana?

While over 300 films shot in nearby Tucson, there’s no documented film history in Adamana itself. You’ll find location scouting focused on Marana and Old Tucson Studios instead.

Did Any Famous Historical Figures Ever Visit or Stay in Adamana?

The most notable famous visitor was conservationist John Muir, who stayed at the Forest Hotel in 1904 with his daughters. His presence brought significant historical significance to this railroad stop.

What Wildlife and Plant Species Are Commonly Found Around Adamana?

You’ll encounter diverse desert wildlife including coyotes, mule deer, and javelina, alongside native plants like prickly pear cactus, juniper trees, and seasonal wildflowers blooming in spring’s gentle embrace.

References

- https://www.onlyinyourstate.com/trip-ideas/arizona/az-route-66-ghost-towns

- https://janmackellcollins.wordpress.com/category/arizona-ghost-towns/

- https://janmackellcollins.wordpress.com/2024/08/23/adamana-arizona-the-one-time-gateway-to-the-petrified-forest/

- https://richesmi.cah.ucf.edu/omeka/items/show/6733

- https://www.ghosttowns.com/states/az/adamana.html

- https://www.brucebyersconsulting.com/following-john-muirs-footsteps-in-the-petrified-forest/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_ghost_towns_in_Arizona

- https://kids.kiddle.co/List_of_ghost_towns_in_Arizona

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Santa_Fe

- https://www.trains.com/ctr/railroads/fallen-flags/remembering-the-santa-fe-railway/