You’ll discover Algert, Arizona as a late 19th-century mining settlement that grew from a small camp into a bustling town of 2,000 residents between 1890-1910. The town featured essential services, including a post office, schoolhouse, hospital, and the Blue Canyon Trading Post, established by Charles Algert in 1891. While mining operations initially drove its prosperity, institutional abandonment led to its decline by 1921. Today, the ghost town’s crumbling adobe structures and mining remnants offer glimpses into Arizona’s frontier past.

Key Takeaways

- Algert was a late 19th-century mining town in Arizona that grew to nearly 2,000 residents during its peak between 1890-1910.

- The town’s economy centered on gold and silver mining, with essential services including a post office, schoolhouse, hospital, and general stores.

- Blue Canyon Trading Post, built by Charles Algert in 1891, served as a vital commercial hub for local Native American communities.

- The town’s decline began with institutional abandonment, particularly after the Indian Service relocated to Tuba City in 1903.

- Today, Algert is an unmaintained ghost town accessible only by 4WD vehicles, featuring deteriorating structures and scattered mining equipment.

The Origins of Peck Canyon’s Trading Post

Despite persistent local legends about a trading post in Peck Canyon, historical records reveal that no formal trading establishment ever existed in this rugged terrain near Nogales, Arizona.

You’ll find that the canyon’s history instead centers on homesteading efforts from the late 1800s, when settlers braved the isolated landscape in search of agricultural opportunities.

While you might expect to discover evidence of a trading post given the area’s frontier location, documented commercial activity was limited to informal bartering among homesteaders.

The challenging geography and sparse population couldn’t support a proper trading establishment.

Unlike successful trading posts that required reliable water supplies, Peck Canyon’s unpredictable water sources made it unsuitable for permanent commercial operations.

Historical accounts of Peck Canyon focus primarily on subsistence farming, ranching, and unfortunately, violent conflicts with indigenous groups.

The closest trading posts were located in larger settlements and along established travel routes, leaving Peck Canyon’s economy largely self-contained.

Much like Padre Canyon to the west, the area’s rugged terrain and isolation made it unsuitable for sustained commercial development.

Life at Blue Canyon Trading Post

When Charles Algert established the Blue Canyon Trading Post in 1891, he built a sturdy 70-by-30-foot structure from native blue limestone that would become an essential commercial and cultural hub for the region’s Navajo and Hopi communities.

You’d find the trading post bustling with activity as Native Americans traded their handcrafted blankets, baskets, and ceremonial textiles for necessities like Blue Bird Flour, metal cookware, and ammunition.

The post served as more than just a commercial center – it hosted community gatherings and cultural exchanges that helped preserve Native traditions. The trading post’s location later became home to the Western Navajo Training School, where local Native American children would be sent for education and assimilation. The school began with fourteen Navajo students and gradually expanded despite its rustic conditions.

Mrs. T.M. Alexander’s Legacy

Although the town’s name evolved from Alexandra to Algert, Mrs. T.M. Alexander’s legacy endures as one of Arizona’s pioneering women who helped establish this frontier mining community.

You’ll find her influence deeply woven into the historical narratives of Coconino County, where she and her husband T.M. Alexander, along with Col. Bigelow, laid out the original townsite at Peck mine.

The walls of school buildings and trading post still stand as silent witnesses to the town’s former vitality.

As the first female resident and co-founder, she broke traditional gender barriers of the territorial period, setting a precedent for women’s roles in Western settlement.

Today, while Algert stands as a ghost town with only remnant walls, her story continues to resonate through historical records and place names, offering valuable insights into the essential contributions of women in Arizona’s mining frontier.

Like many barren sites in Arizona, most of the original structures have completely disappeared from view.

Daily Operations and Commerce

The establishment of Blue Canyon Trading Post in 1882 marked the beginning of Algert’s commercial operations, with prospector-turned-trader Jonathan P. Williams at the helm. Trading dynamics centered on essential supplies for miners, Native Americans, and settlers, creating a crucial commercial hub for the frontier community. The town’s cool winter climate made it an ideal location for storing and preserving trading goods. Much like the bar that burned down in Nothing, Arizona, Algert’s primary gathering place was eventually lost to time.

You’d have found the town’s commerce intensifying after 1900 when C.H. Algert established the post office and the Indian Service built its agency and school. These federal operations transformed local commercial interactions, bringing government employees and increased economic activity.

However, Algert’s prosperity proved short-lived. When the Bureau of Indian Affairs relocated to Tuba City in 1903, the town’s commercial significance began to wane. Under Hubert Richardson’s management, the trading post persisted until 1921, but limited infrastructure and regional economic shifts ultimately led to its closure.

Supporting the Mining Industry

Mining operations in Algert depended heavily on an intricate support network of commercial enterprises and infrastructure that emerged during the late 1800s.

You’ll find that companies like Albert Steinfeld & Company played a significant role in supplying mining innovations, from rock drills to ore cars, while also providing essential banking services through the Consolidated National Bank.

The area’s mining economic impact grew substantially when ASARCO built modern reduction works in 1938, creating a regional processing hub that served multiple operations.

Production statistics and data from 1875-1929 show steady growth in the district’s output of copper, lead, silver and gold.

You’d have seen wagons hauling silver and lead ore to nearby smelters, while the Southern Pacific Railroad connected Algert’s mines to national markets.

This support system transformed isolated mining camps into an integrated district, though it ultimately couldn’t prevent the industry’s decline when processing facilities closed in the 1960s.

Following the Great Depression crash, many smaller copper mining operations in the area were forced to shut down, with only a few larger mines remaining operational.

The Settlement’s Peak Years

During its peak years between 1890 and 1910, Algert transformed from a modest mining camp into a bustling settlement of nearly 2,000 residents. The mining boom brought rapid development, with adobe and wooden structures sprouting up to serve the growing population.

You’d have found essential services like a post office, schoolhouse, and hospital, alongside numerous saloons and general stores that formed the backbone of the community structure.

Life centered around the mines, but Algert wasn’t just a work camp. The town developed a rich social fabric with churches, community events, and a local law enforcement presence.

Beyond its mining operations, Algert thrived as a true community, complete with spiritual life, social gatherings, and organized law enforcement.

While the streets remained unpaved, you would’ve seen early electrical systems and basic utilities supporting daily life. The railroad connection guaranteed steady movement of ore and supplies, keeping the town’s economy vibrant.

Decline and Abandonment

While many ghost towns succumbed to depleted mines, Algert’s decline stemmed from institutional abandonment rather than mineral scarcity.

The community’s economic sustainability took a critical hit when the Indian Service relocated its operations to Tuba City in 1903, taking the school and agency with it. You’ll find that the closure of the post office that same year further isolated the settlement, accelerating its community decline.

Despite attempts by traders like Hubert Richardson to maintain commercial activity, Algert couldn’t survive without its core institutions.

By 1921, the last business ventures had ceased, leaving only deteriorating walls of the former school and trading post.

Today, you can still see these remnants, which stand as silent witnesses to a settlement that faded not from resource depletion, but from institutional withdrawal.

What Remains Today

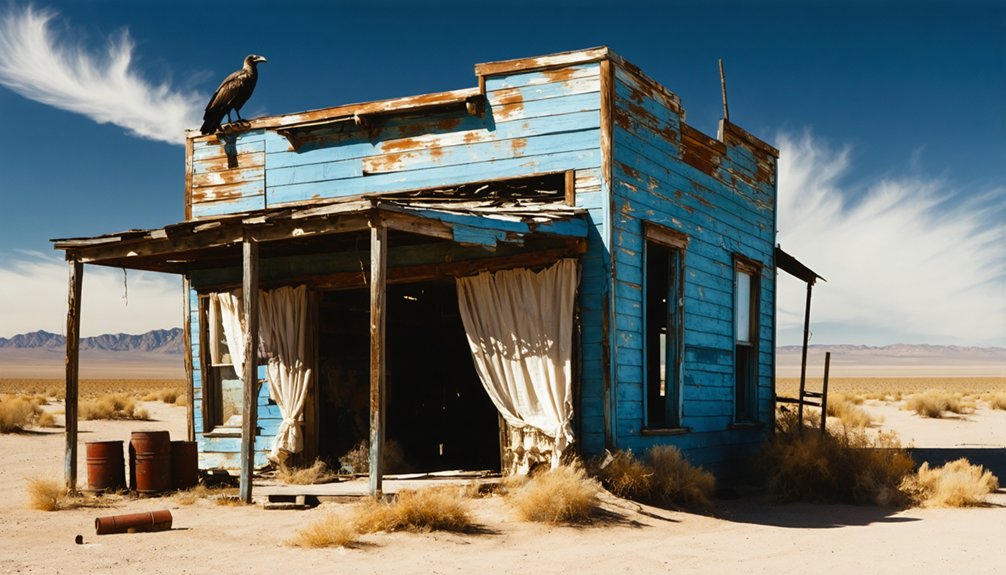

You’ll find crumbling adobe walls and scattered mining equipment among the overgrown desert vegetation at Algert’s original townsite.

The site’s deteriorating structures and unstable ground near old mine shafts present significant safety hazards for modern visitors.

While accessible via unpaved desert roads, you should exercise extreme caution when exploring the remains, as the remote location offers no facilities or emergency services.

Physical Site Condition

The remnants of Algert stand as a stark tribute to the harsh desert environment that has slowly reclaimed this neglected Arizona ghost town.

You’ll find little more than scattered ruins and foundations where buildings once stood, as decades of site deterioration have taken their toll. The wooden and adobe structures have largely collapsed, leaving only partial walls and exposed beams to mark their former locations.

Natural reclamation is evident everywhere you look.

Desert vegetation now dominates the landscape, with sagebrush and mesquite growing freely among the rubble. Rusting mining equipment and fragments of daily life – broken glass, pottery shards, and metal containers – litter the ground.

The site remains completely unmaintained, with no preservation efforts in place to halt its gradual return to the desert.

Access and Safety Concerns

Reaching Algert’s deteriorating remains requires careful planning and preparation due to its remote desert location.

You’ll need a high-clearance or 4WD vehicle to navigate the rough, unpaved access routes that lead to this forgotten mining settlement. The site’s isolation and lack of cellular coverage make safety precautions essential for any visit.

- GPS coordinates or local guidance are necessary, as the site isn’t marked on most maps

- Pack ample water, emergency supplies, and first-aid equipment

- Watch for physical hazards including unstable structures, sharp debris, and mining equipment

- Be aware of desert wildlife threats like rattlesnakes and scorpions

- Check weather conditions and land ownership status before attempting access

The lack of maintained facilities and formal signage means you’re largely on your own when exploring these historic ruins.

Historical Significance

You’ll find Algert’s origins uniquely tied to Jonathan P. Williams’s decision to establish a trading post rather than pursue mining directly, setting it apart from typical boomtowns of 1880s Arizona.

The trading post’s strategic role in supporting nearby mining communities through essential supplies and services demonstrates how non-mining enterprises were crucial to frontier development.

Algert’s evolution from Blue Canyon Trading Post to a small settlement reflects broader patterns of how trading centers helped sustain Arizona’s mining frontier, even when the settlements themselves remained modest in size.

Trading Post Origins

During the late 19th century, Algert’s Trading Post emerged from humble beginnings as a small store rented from a Navajo hogan named Musha near Musha Springs.

When sand disrupted business operations in the original location, Algert seized an opportunity to relocate a quarter mile west in 1891, purchasing land from a Mormon settler to establish what would become the renowned Tuba Trading Post.

- Built a strategic shed-roofed store that served as a crucial commercial hub

- Facilitated trade between Mormon settlers and Native American communities

- Leveraged fluency in Navajo and Hopi languages to build trust

- Created a cultural crossroads for exchanging indigenous goods

- Established lasting relationships that influenced regional trading networks

This trading post history exemplifies how community interactions shaped the economic landscape of the American Southwest.

Supporting Mining Communities

While silver, lead, and zinc drew prospectors to Algert’s rich mineral deposits, the town’s true significance lay in its role as a vital support hub for the surrounding mining operations.

You’ll find that Algert’s mining infrastructure included essential facilities like smelters and reduction mills, which processed ore locally to maximize efficiency and reduce transportation costs.

The town’s labor dynamics reflected the diverse makeup of Arizona’s mining communities, with immigrants and Mexican workers joining local miners in the dangerous underground work.

These workers faced challenging conditions, including toxic gases and physically demanding tasks.

Beyond the mines, Algert supported a network of services, from blacksmiths to general stores, creating a self-sustaining micro-economy that helped the community thrive during peak production periods.

Frontier Settlement Patterns

Before Algert emerged as a mining settlement, the region’s frontier development reflected centuries of overlapping cultural patterns, from ancient Paleo-Indian inhabitants to Spanish colonists and American pioneers.

You’ll find that frontier lifestyles in this area were shaped by the harsh desert environment and the complex cultural interactions between Indigenous peoples, Spanish missionaries, Mexican ranchers, and American settlers.

- Indigenous communities established the first settlements near water sources, developing sophisticated irrigation systems.

- Spanish presidios and missions created centers of colonial control in the 17th century.

- Apache resistance greatly influenced settlement patterns in northern and eastern Arizona.

- The Gadsden Purchase of 1853-1854 opened new opportunities for American frontier expansion.

- Military posts and supply routes became focal points for emerging frontier communities.

Visiting the Ghost Town Site

As you venture into the remote reaches of Coconino County, the abandoned site of Algert presents itself as a quiet symbol of Arizona’s frontier past.

Tucked away in Coconino County’s vast expanse, Algert’s weathered ruins whisper stories of Arizona’s pioneering spirit.

You’ll discover partial walls and foundations of the former trading post and school buildings, perfect for ghost town exploration and site photography. While 2WD roads make the location accessible, you’ll need to prepare thoroughly for your visit since no facilities or services exist nearby.

For the safest experience, plan your exploration during cooler seasons and bring essential supplies including water, food, and navigation tools.

You won’t find interpretive signage or guided tours here – just the raw remnants of frontier history waiting to be discovered on your own terms. Remember that cell service is nonexistent, so self-reliance is vital.

Frequently Asked Questions

What Role Did Native American Traders Play in Algert’s Economy?

You’ll find Native Americans drove essential trade networks through wool, crafts, and local goods exchange, creating significant economic impact while connecting Algert’s post to broader regional markets beyond reservation boundaries.

Were There Any Notable Conflicts or Crimes Recorded in Algert?

Amid the windswept ruins and fading echoes of time, you’ll find no documented historical crimes or conflicts in this remote outpost. Even ghostly encounters remain absent from official records and tribal accounts.

What Type of Vegetation and Wildlife Exists Around the Site Today?

You’ll find hardy desert flora like sagebrush, juniper, and piñon pine thriving around the site, while wildlife diversity includes mule deer, coyotes, jackrabbits, and various desert-adapted birds and reptiles.

Did Any Stagecoach Routes or Major Trails Pass Through Algert?

You won’t find documented stagecoach history or major trails running through this site. While local paths served miners and indigenous communities, there’s no evidence of significant transportation routes passing directly through here.

What Weather Conditions Contributed to the Deterioration of Algert’s Buildings?

Imagine a wooden beam cracking under intense heat – that’s what happened here. Wide temperature swings, wind-driven rain, UV radiation, and freeze-thaw cycles steadily weakened building materials until structures failed.

References

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ajDJao0rpv0

- https://kids.kiddle.co/List_of_ghost_towns_in_Arizona

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_ghost_towns_in_Arizona

- https://jauntingjen.com/2022/05/10/ghost-towns-on-the-arizona-border-lochiel/

- https://www.thedieselapartment.com/southern-arizona-ghost-town-alto-camp/

- https://www.ghosttowns.com/states/az/algert.html

- https://www.ghosttowns.com/states/az/azalphabetical.html

- https://lib.arizona.edu/about/news/archive-tucson-oral-history-spotlight-life-1930s-mining-camp

- https://www.theroute-66.com/twin-arrows.html

- https://visitfourcorners.com/navajo-trading-posts-in-the-four-corners/