Cascabel, Arizona isn’t a typical ghost town but a fading rural community named for rattlesnakes along the San Pedro River. You’ll find remnants of the once-thriving agricultural settlement that flourished in the late 1800s before declining after the 1887 Sonora earthquake, Great Depression, and WWII. Today, conservation efforts have transformed the area into an ecological preserve. The stories of indigenous Sobaipuri farmers, pioneer ranchers, and environmental challenges await beyond these abandoned homesteads.

Key Takeaways

- Cascabel is a ghost town along Arizona’s San Pedro River named after a rattlesnake encounter, reflecting the Southwest’s frontier character.

- Agricultural decline began with the 1887 Sonora earthquake, worsened during the Great Depression, and culminated after World War II.

- The community’s vital infrastructure collapsed with the schoolhouse closure in 1916 and post office shutdown in 1936.

- Veteran exodus after World War II due to housing affordability issues and declining employment contributed to Cascabel’s ghost town status.

- Since the 1980s, conservation efforts have transformed Cascabel into an ecological preservation model with 1,800 acres in conservation easements.

The Origin Story: How Cascabel Got Its Rattlesnake Name

Inspired by this chance meeting, Herron adopted the name for his community’s post office, which operated until 1936.

This naming reflects the cultural significance of rattlesnakes in the Southwest, where they were common enough to influence settler experiences. Cascabel, which means “rattlesnake” or “little bell” in Spanish, is situated along the San Pedro River north of Benson. The community spans approximately 40 miles in length and 10 miles in width along the river valley.

The rattlesnake symbolism became deeply embedded in local identity, representing both the dangers and distinctive character of this frontier community along the San Pedro River.

First Settlers: Native Americans and Pioneer Families

The Sobaipuri, a subgroup of the O’odham people, established the first agricultural settlements along the San Pedro River near Cascabel, growing crops in the fertile valley soil before Apache conflicts displaced them in the mid-19th century.

You’ll find evidence of these indigenous communities in pottery fragments and stone artifacts that still emerge from the soil today, silent testimonies to centuries of Native American presence.

The valley’s cultural significance extends through generations, with the San Pedro Valley recognized as one of the last ecologically intact landscapes in the United States, preserving not only natural beauty but also ancestral connections to the land.

The area later attracted diverse community members who came together in 1994 to protect the land from a militia group that sought to purchase Hot Springs Canyon for a firing range.

Indigenous Agricultural Practices

Ancient ingenuity defined the agricultural practices of Native Americans who first settled the Cascabel region, beginning at least by 2100 BCE.

You can see evidence of their sophisticated understanding of desert farming through the indigenous crops they cultivated: maize, beans, squash—the “Three Sisters” intercropping system—alongside cotton and agave.

Their sustainable practices included irrigation canals, terraces, and rock mulches that maximized water efficiency in this arid landscape.

They strategically positioned settlements along river valleys to harness nutrient-rich silt deposits and employed controlled burns to enrich soil.

These agricultural innovations transformed mobile hunter-gatherer societies into permanent settlements with specialized labor and trade networks.

The shift to farming fundamentally reshaped community identities and social structures, creating the foundation for complex societies like the Hohokam that thrived long before European contact.

Archaeological discoveries reveal that native peoples cultivated at least eight domesticated agave species that were specially bred to mature faster and provide sweeter harvests than their wild counterparts.

Without draft animals or metal tools, native farmers relied on simple implements like dibble sticks for planting their crops in the challenging desert environment.

Pioneer Family Homesteads

Long before Mexican and Anglo settlers arrived in 1865, Sobaipuri people had established a presence in the San Pedro Valley near Cascabel. Their settlements were minimal, with population estimates in the late 1680s ranging from 280 to 575 people.

When pioneer families like the Bayless family began establishing ranches in 1885, they faced tremendous agricultural challenges. Apache resistance forced many to abandon their homesteads temporarily.

You’d find these early settlers demonstrating remarkable pioneer resilience, surviving through ranching and subsistence farming in isolated conditions with limited water and arable land. Similar to settlers in Yavapai County who discovered significant gold deposits in the 1860s, these pioneers sought to establish economic foundations in harsh frontier conditions.

Despite the hardships, descendants of these determined families, including the Bayless and Smallhouse families, continue operating ranches today.

Their legacy of cooperation and self-sufficiency lives on in Cascabel’s sparse but tight-knit community, where historical preservation efforts maintain the area’s distinctive rural character. The struggle between pioneers and indigenous groups reflects the broader Apache Wars that dominated Arizona’s territorial period for nearly forty years.

River Valley Communities

Before European settlers arrived in Arizona’s river valleys, sophisticated Indigenous civilizations had already established thriving agricultural communities for thousands of years. The Hohokam masterfully engineered extensive canal systems between 600-900 C.E., demonstrating remarkable cultural resilience in the harsh Sonoran Desert environment.

Following the Hohokam’s mysterious decline around 1450 A.D., the O’odham and Piipaash peoples continued their irrigation techniques while adapting to changing conditions. Their sustainable practices enabled survival despite limited resources.

The 18th century brought dramatic changes as Spanish and Mexican colonization disrupted native settlements. Many communities consolidated or relocated as traditional water access diminished. Father Eusebio Kino’s establishment of San Xavier Mission in 1700 marked a significant cultural transition in the region.

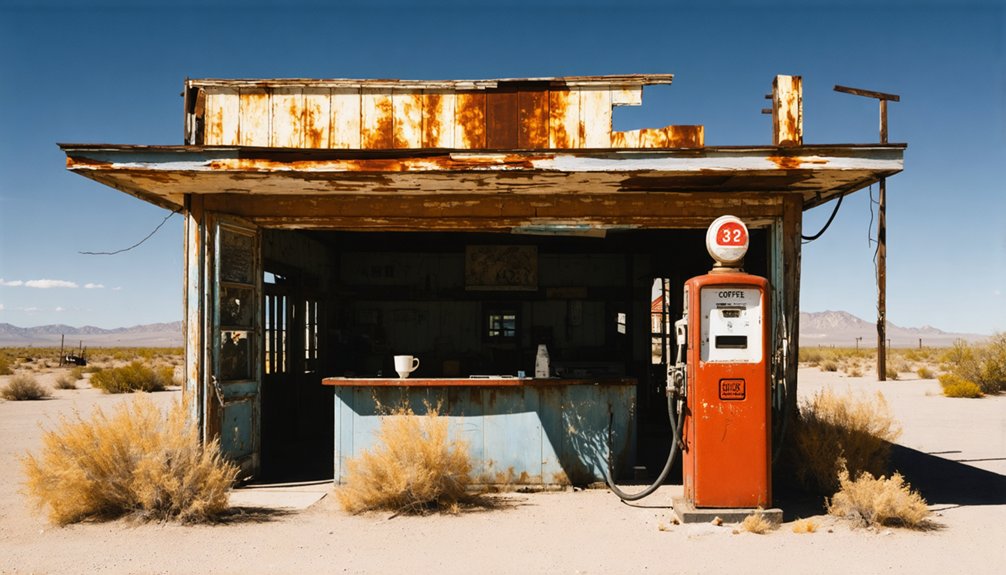

The Ebb and Flow of the Post Office (1902-1936)

Communication lifelines for remote settlements were established in the San Pedro River Valley when the Pool Post Office opened in 1902 at Mr. Pool’s ranch, providing essential postal services to isolated homesteaders for 11 years until its closure in 1913.

Alex Herron, a local rancher and shopkeeper, recognized the community’s need and sought to reestablish mail service. When postal authorities rejected reusing the “Pool” name, Herron drew inspiration from a chance encounter with a rattlesnake, naming the new facility “Cascabel.”

Beyond mail delivery, the Cascabel Post Office functioned as a community connection point alongside the store and nearby schoolhouse, sustaining rural livelihoods through access to supplies and information. This exemplified how the postal system helped reduce rural isolation by connecting even the most remote communities to the wider world.

Despite residents’ persistence, economic hardship and population decline ultimately led to the post office’s discontinuation in 1936, symbolizing Cascabel’s shift toward ghost town status.

Life Along the San Pedro River Valley

The San Pedro River Valley harbors one of North America’s most remarkable archaeological records, with evidence of human habitation stretching back nearly 13,000 years to the Clovis culture.

You’re walking through a living timeline where hunter-gatherers once tracked mammoth before evolving to early agriculture. Their platform mounds and villages still dot the landscape.

The river’s northward flow created unique ecosystems where the Chihuahuan and Sonoran Deserts meet, supporting hundreds of species.

Local Cascabel myths often intertwine with the area’s natural elements, particularly rattlesnake folklore—hardly surprising for a settlement named after the Spanish word for “rattlesnake.”

Beaver ponds once dominated before ranching transformed the valley in the 1800s, changing waterflow patterns that indigenous peoples had managed for millennia.

Earthquakes and Environmental Changes That Shaped Destiny

As you walk along the banks of today’s San Pedro River, you’re treading on ground profoundly transformed by the 1887 earthquake that ruptured the Pitaycachi fault with displacements of up to 16 feet.

This seismic event dramatically altered the river’s course and hydrology, triggering a cascade of environmental changes that first devastated local ranching operations during the 1891-1893 drought, then caused destructive flooding in 1894.

The geological turning point marked by this earthquake, followed by decades of water challenges that weren’t addressed until electrical pumping arrived in the 1950s, effectively determined Cascabel’s trajectory toward eventual abandonment.

River Flow Disruptions

When southeastern Arizona shuddered under the powerful 7.6 magnitude Sonora earthquake of 1887, Cascabel’s destiny was forever altered by dramatic changes to the San Pedro River system.

The earthquake created massive ground fissures extending over 100 km, with vertical displacements up to 16 feet that permanently changed river flow gradients and sediment transport patterns.

You would have witnessed extraordinary phenomena: water geysers erupting from fractured earth, ponds vanishing while new ones formed elsewhere, and the river itself seeking new paths through the disrupted landscape.

The seismic activity triggered aftershocks for decades, repeatedly reshaping river morphology and local hydrology.

For Cascabel’s residents, these unpredictable river flow changes undermined agricultural viability and water security, ultimately contributing to the community’s decline as nature reclaimed its freedom to carve new waterways.

Agricultural Decline Timeline

Following the cataclysmic 1887 Sonora earthquake that rewrote Cascabel’s hydrological future, a series of economic and environmental challenges unfolded across subsequent decades to gradually suffocate local agriculture.

The 1930s delivered a double blow—severe drought and Great Depression hardships—forcing many unfenced ranches to consolidate under new Taylor Grazing Act requirements.

You’d have witnessed community resilience tested as traditional agricultural practices faltered.

World War II further undermined local farming when young ranch hands enlisted and rarely returned to agricultural life.

Geological Turning Points

The 1887 Sonoran Earthquake, registering a powerful M7.6 near the Arizona-Mexico border, established the geological foundation for Cascabel’s eventual decline.

This seismic activity reshaped the region’s underlying fault systems, particularly affecting the complex geological formations near Horseshoe Reservoir where surface ruptures have repeatedly occurred.

You’ll find evidence of Cascabel’s unstable foundation in the volcaniclastic deposits that dominate the landscape, their disrupted patterns telling a story of repeated disturbances.

By the early 20th century, moderate earthquakes (M5.0-M6.2) continued destabilizing groundwater pathways vital to farming.

The fault-controlled sediment patterns beneath the San Pedro River were further compromised when agricultural pumping intensified during drought periods, fundamentally sealing Cascabel’s fate by altering the hydrological systems that once supported its community.

The Schoolhouse: Education and Community Gathering Place

Built in 1885, Cascabel’s schoolhouse served as the heart of the community for decades, providing not only education but also an essential gathering place for area residents.

The modest structure, constructed of locally-sourced materials with a sandstone foundation and ponderosa pine walls, was remarkably well-equipped for rural Arizona standards. You’d find factory-made desks for two pupils, large blackboards, Webster’s dictionary, and even a pump organ inside.

Despite its frontier origins, the schoolhouse boasted modern amenities that belied its remote desert location.

When children weren’t studying, the building transformed to host community events including religious services, dances, and social meetings. This multi-purpose venue strengthened social bonds among isolated frontier families.

The schoolhouse’s educational legacy ended in 1916 due to declining enrollment. Though Cascabel’s original structure was demolished in the 1970s, the site continues as a community center where reunions celebrate its historical significance.

Economic Hardships and Population Decline

You’ll find Cascabel’s economic vitality declined considerably during the Great Depression when families struggled to maintain their ranches amid financial ruin.

The situation worsened when the post office closed in 1936, removing an essential community service and signaling Cascabel’s diminishing importance.

After World War II, the population dwindled further as returning veterans chose urban opportunities over ranching life, accelerating the area’s transformation into a ghost town.

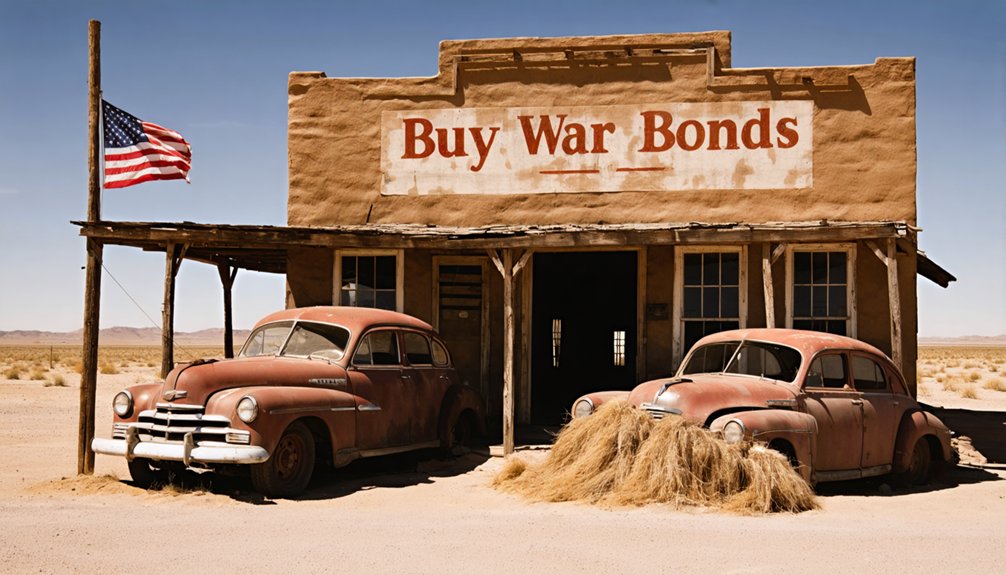

Great Depression’s Crushing Impact

Devastation swept through Cascabel during the Great Depression, transforming what had been a modest but functioning agricultural community into a shell of its former self. The collapse of agricultural markets demolished any hope of economic resilience, with cotton crops simultaneously ravaged by drought and pink bollworms.

You’d have witnessed widespread unemployment as mining and lumber industries contracted alongside farming. Families abandoned their homes in droves, seeking better prospects in urban centers where relief was more accessible.

The community’s potential for agricultural innovation vanished as young men joined the military during World War II, rarely returning to rural life. Migrant workers faced particularly cruel circumstances—often stranded without resources, enduring starvation before forced repatriation.

For minority residents, discrimination intensified as they were systematically excluded from the limited New Deal programs reaching the area.

Post-Office Closure Effects

When the post office shuttered its doors in Cascabel, the community lost far more than a mail delivery point—it lost its economic lifeline and social anchor.

Without access to the postal service, you’d face lengthy drives to neighboring towns just to collect mail or ship packages, straining already tight budgets.

Local businesses crumbled as their ability to conduct commerce evaporated. Property values plummeted while incidental sales at nearby shops disappeared.

The town’s community identity, once reinforced through daily postal interactions, began to dissolve.

The effects snowballed quickly: younger residents relocated to areas with better services, leaving behind an aging population.

This triggered a vicious cycle—fewer residents meant fewer services, making the area increasingly unviable.

What remained was a shell of a once-thriving community, isolated and economically crippled.

Veterans’ Mass Exodus

As the economic lifeblood of Cascabel continued to drain following the post office closure, the town’s veteran population began a notable exodus, mirroring broader Arizona trends where veteran numbers declined by 13.62% since 2012.

Veterans faced mounting challenges typical across the state—housing affordability issues, declining employment rates, and fixed incomes stretched thin by rising costs.

Though Cascabel-specific data remains scarce, you’ll recognize the migration patterns: older veterans relocated to established retirement communities like Sun City, where affordability and amenities supported their limited finances.

The area’s once-significant veteran concentration, likely similar to Cochise County’s 19% rate, dwindled as economic pressures intensified.

For many former service members, Cascabel’s isolation and diminishing resources simply became untenable, accelerating the community’s transformation into a ghost town.

World War II’s Impact on the Dwindling Community

World War II dealt a decisive blow to Cascabel’s already fragile community structure, accelerating population decline that had begun in the 1930s. As ranch-raised young men enlisted and left the area, demographic shifts became permanent when many veterans chose not to return after experiencing wider economic opportunities elsewhere.

You’ll notice the war marked a definitive end to the subsistence lifestyle that had sustained Cascabel. Residents lost faith in making a living by the river, and the arrival of electricity in the late 1950s came too late to reverse the exodus.

Unlike other Arizona regions experiencing postwar growth, Cascabel remained isolated as Interstate 10’s construction bypassed the area.

The consequences were profound—working-age residents vanished, economic activity withered, and Cascabel evolved from a viable agricultural community to fundamentally a ghost town until limited resettlement in the 1980s.

Preservation Efforts in a Unique Agricultural Ghost Town

Despite Cascabel’s decline into ghost town status, preservation efforts since the 1980s have transformed this forgotten agricultural settlement into a model of conservation. The Cascabel Conservation Association (CCA) has secured approximately 1,800 acres through conservation easements with local landowners, protecting one of Arizona’s most intact landscapes from development threats like the proposed I-10 bypass.

You’ll find community involvement thriving in expanded garden programs and orchards, particularly on the 130-acre Baicatcan property where sustainable agriculture practices maintain ecological balance.

Conservation practices extend to historical structures—old ranch buildings and mining sites—which now stand protected alongside modern hermitage retreats that embrace off-grid living.

The CCA’s documentation initiatives preserve oral histories and cultural traditions, ensuring that even as a ghost town, Cascabel’s heritage remains alive through deliberate stewardship.

Modern Cascabel: Wildlife Sanctuary and Historical Landmark

Modern Cascabel has evolved beyond mere preservation efforts into a thriving wildlife sanctuary and historical landmark of regional significance. The Oasis Sanctuary, established in 1997, now occupies 71 acres with a specialized 1,300-square-foot facility for wildlife rehabilitation of birds with special needs.

Meanwhile, the Cascabel Conservation Association manages 1,800 acres dedicated to ecological preservation, protecting vital wildlife corridors along Hot Springs Canyon within the San Pedro River Valley. These conservation areas link directly to indigenous Sobaipuri settlements, merging cultural heritage with environmental stewardship.

You’ll find the sanctuary’s 21-acre pecan orchard providing seasonal canopy for diverse bird species, while the off-grid amenities at Corbett Retreat demonstrate sustainable practices within wildlife habitats.

Visit by appointment to witness how this former ghost town now sustains biodiversity through community-led conservation initiatives.

Frequently Asked Questions

Are There Guided Tours Available of Cascabel’s Remaining Structures?

Unlike Arizona’s Tombstone where “boot hill” draws crowds, you won’t find guided tours of Cascabel’s historically significant remains. You’ll need to explore independently, discovering local legends and structural remnants on your own terms.

What Happened to Descendants of Original Cascabel Settler Families?

You’ll find that many descendants continued ranching traditions, while others dispersed to nearby communities. Family legacies persist through conservation efforts, with descendant stories preserved by the Cascabel Community Center’s documentation initiatives.

How Accessible Is Cascabel for Visitors With Mobility Limitations?

Will you manage? Cascabel offers virtually no wheelchair accessibility or visitor accommodations. You’ll face unpaved roads, rough terrain, and natural obstacles without ramps, paved paths, or adapted facilities. Bring all-terrain mobility equipment.

Can Visitors Legally Collect Artifacts Found in Cascabel?

No, you shouldn’t collect artifacts in Cascabel. Legal restrictions typically prohibit removal from public lands, and artifact preservation ethics demand leaving items undisturbed. Always check land ownership before exploring ghost town remnants.

What Paranormal Activity Has Been Reported in Cascabel?

You’ll find reports of whispering voices, unexplained footsteps, and shadow figures in abandoned buildings. Ghost sightings often occur at night near adobe structures, with haunted locations typically including former saloons and homesteads.

References

- https://www.tombstonetraveltips.com/cascabel-arizona.html

- https://www.arizonahighways.com/article/arizona-ghost-towns

- https://cascabel.org/history/

- https://kids.kiddle.co/List_of_ghost_towns_in_Arizona

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_ghost_towns_in_Arizona

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=__EvnO3EFjw

- https://www.ghosttowns.com/states/az/azalphabetical.html

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cascabel

- https://a-z-animals.com/animals/cascabel/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Crotalus