Duquesne, Arizona is a ghost town 17 miles east of Nogales where George Westinghouse’s mining empire once thrived. Founded in 1889, it peaked with nearly 1,000 residents by 1912, extracting over 450,000 tons of zinc, lead, copper, and silver ore before collapsing after 1918. Today, you’ll find Victorian ruins and mining remnants on private property, accessible via rough dirt roads requiring high-clearance vehicles. The site’s multicultural history awaits beyond the “No Trespassing” signs.

Key Takeaways

- Duquesne was a copper mining boomtown established in 1889 by George Westinghouse that peaked with 1,000 residents in 1912.

- Located 17 miles east of Nogales in Santa Cruz County, Duquesne is accessed via challenging dirt roads requiring high-clearance vehicles.

- Notable structures include Westinghouse’s Victorian mansion, frame houses, a boarding house, and an adobe commercial building.

- The town quickly declined after 1918 when mining operations ceased, transforming it into a ghost town.

- Most structures are on private property with “No Trespassing” signs, though limited preservation efforts are underway.

The Mining Boom That Built Duquesne

The establishment of the Duquesne Mining and Reduction Company in 1889 marked a pivotal turning point for this once-thriving Arizona settlement. As silver values declined after 1883, the company strategically shifted to copper extraction, developing sophisticated mining techniques that transformed the region’s economy.

You’ll find the company’s legacy in their impressive 1,600-acre operation that spanned over 80 mining claims. According to production statistics compiled for Arizona mining districts, Duquesne contributed significantly to the territorial copper output. They built reduction plants in both Washington Camp and Duquesne, enabling on-site processing of valuable ores.

These facilities attracted nearly 1,000 residents to each settlement by 1900, creating bustling communities with essential services. The company’s innovative approach to copper extraction met growing industrial demand, temporarily liberating this remote area from economic obscurity before operations eventually ceased, leaving behind the ghost town you can explore today. Visitors can now appreciate this unique historical site through a browser check process that verifies authenticity before accessing detailed information about the mining town.

Journey Through Time: Accessing the Ghost Town

Maneuvering to Duquesne’s weathered remains offers modern explorers a chance to traverse the same rugged paths that once bustled with miners and merchants.

Located 17 miles east of Nogales in Arizona’s Santa Cruz County, you’ll need to navigate Harshaw Road (FR 58) to its junction with Duquesne Road (FR 61), then follow a challenging 23-mile dirt road through historic landscapes.

Access challenges abound as you approach the townsite via the rough spur road (FR 128). Given the mountainous terrain, high-clearance or 4WD vehicles are essential.

Washington Camp lies less than a mile north, accessible through the same network. Remember that Duquesne is privately owned with restoration in progress—respect all no-trespassing signs, particularly around dangerous mining shafts and tailings dumps.

The area’s development was significantly hindered by Apache Indian attacks until the 1880s when settlement finally took hold.

Situated at approximately 5,500 feet elevation, the ghost town offers visitors breathtaking views of the surrounding Patagonia Mountains landscape.

Bring maps, water, and supplies; cell service is minimal.

Westinghouse’s Legacy in the Arizona Borderlands

When George Westinghouse purchased most of the Patagonia mining claims in 1889, he fundamentally transformed the Arizona borderlands’ economic landscape. His establishment of the Duquesne Mining and Reduction Company catalyzed unprecedented regional growth, converting a frontier settlement into a thriving community of 1,000 residents.

Westinghouse investments extended beyond mere extraction of silver, lead, and zinc. You’ll find his influence embedded in the infrastructure he developed—housing, schools, and commercial enterprises that served both Duquesne and Washington Camp.

His corporate approach exemplified late 19th-century industrial consolidation, while simultaneously shaping mining policies throughout the territory. This approach stands in contrast to modern mining ventures like Resolution Copper, which faces significant resistance due to sacred land issues.

The legacy of these operations persists in today’s landscape. His Victorian frame house ruins still stand as a silent testament to his presence in the area. As you explore the ghost town, you’re witnessing the physical remnants of an industrial titan’s vision that once breathed economic significance into these arid mountains.

Daily Life in a Turn-of-the-Century Mining Community

As you explore the ruins of Duquesne today, you’ll need to imagine the backbreaking labor of miners who endured dangerous conditions, working lengthy shifts deep within the earth for modest wages.

The social landscape was remarkably diverse, with Mexican, European, and American workers creating a multicultural community despite clear social stratification between company officials and laborers. The name Duquesne itself reflects this cultural complexity, as it derives from Norman and Picard French dialects meaning “of the oak.”

After sunset, miners sought relief from their grueling work in the saloons and brothels of Washington Camp, where music, gambling, and drink provided temporary escape from the harsh realities of mining life.

Work Under Harsh Conditions

The brutal realities of Duquesne’s mining operations subjected workers to life-threatening conditions on a daily basis.

You’d descend 300 to 500 feet underground, extracting lead, silver, and copper without proper safety equipment, constantly facing cave-ins and toxic dust exposure. Workers at the Annie Mine particularly struggled with extracting the partly oxidized minerals found in irregular lenses throughout the deposit. Worker safety wasn’t prioritized as you labored through long shifts in darkness and dampness.

Your body would deteriorate from repetitive, strenuous tasks while breathing metal-laden air that slowly poisoned your lungs. Primitive technology meant much of the extraction and milling remained backbreaking manual labor despite limited mechanization.

Community resilience emerged through necessity as you lived in simple structures—tents or basic houses—with minimal medical care available.

The boom-and-bust cycle of mining meant you couldn’t count on stable employment, forcing adaptation to economic uncertainty while enduring harsh desert conditions.

Multicultural Social Fabric

Beyond the harsh confines of the mines, Duquesne’s social landscape reflected a vibrant cultural mosaic where different worlds converged at this remote outpost. You’d witness Anglo-Americans, Mexicans, and Spanish descendants creating an organic bilingual environment near the international border.

The stratified housing—company officials in proper homes, miners in bunkhouses—revealed social hierarchies, yet community gatherings transcended these divisions. You might find miners from different backgrounds sharing stories at the saloon after shifts or families interacting at the centrally-located school that served both Duquesne and Washington Camp.

Cultural exchange flourished despite isolation, with Catholic and Protestant traditions coexisting as families adapted to mining schedules.

The general store became more than a commercial space—it functioned as a hub where diverse residents navigated their shared frontier existence.

Entertainment After Dark

Mining towns like Duquesne transformed after sunset, creating vibrant nightlife scenes that contrasted with the grueling daylight hours spent underground.

You’d find the boarding house doubling as a bar and brothel—the epicenter of Duquesne’s nightlife allure. Here, miners gambled, drank, and sought companionship after long shifts.

The schoolhouse between Duquesne and Washington Camp hosted community gatherings for dances and holiday celebrations, while saloons in adobe structures offered card games and storytelling sessions.

The isolated mountain setting intensified locals’ reliance on creating their own entertainment. Music, often performed by traveling musicians or talented miners, filled the air during community events.

As mining operations declined after 1918, these social spaces gradually emptied, their vibrant nighttime economy fading into silent ruins that now tell of a once-thriving social landscape.

Architectural Remnants: What Survives Today

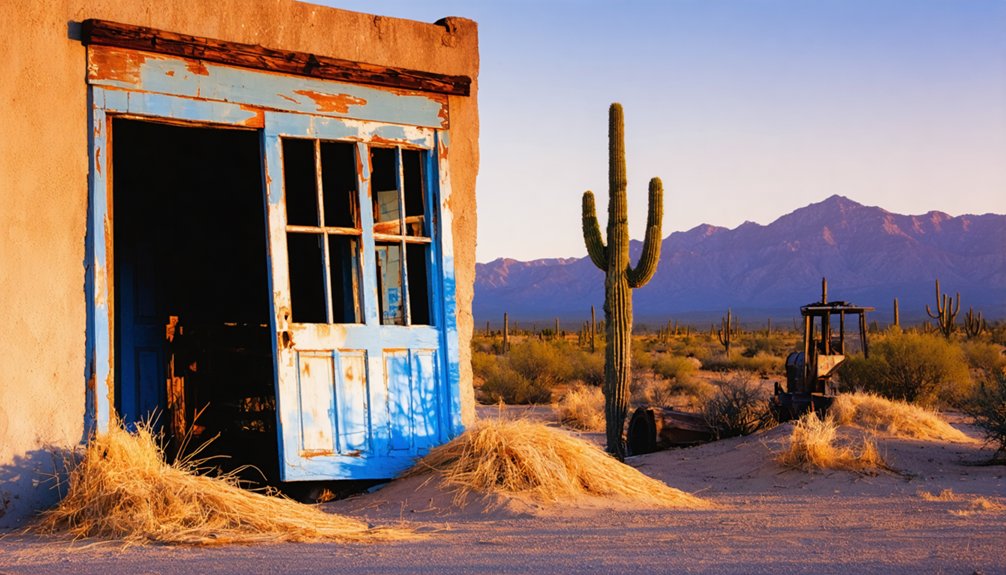

While much of Duquesne’s original architecture has succumbed to time and abandonment, several notable structures remain as silent witnesses to the town’s mining heyday.

You’ll find George Westinghouse’s deteriorating Victorian mansion standing alongside a smaller frame house that exemplifies typical mining-era architectural styles. The large boarding house where miners once rested still persists.

The adobe commercial building showcases local construction methods of historical significance, while foundations of the company office hint at organizational infrastructure. Many ghost towns feature adobe structures that have proven surprisingly resilient against Arizona’s harsh desert elements.

Mining remnants dot the surrounding hills, telling the industrial story that birthed this settlement. The cemetery offers a solemn record of those who lived and died here.

Be aware that most structures sit on private property with strict “No Trespassing” signs, limiting your ability to closely examine these architectural treasures.

The Rise and Fall of Duquesne’s Economy

You’ll find Duquesne’s economic trajectory followed a classic mining boom-bust cycle, with its zenith occurring when the Duquesne Mining & Reduction Company ramped up production in 1912.

The town’s prosperity peaked with nearly 1,000 residents and over 80 mining claims covering 1,600 acres, generating more than 450,000 tons of zinc, lead, copper, and silver ore. Similar to other mining operations in the region, Duquesne benefited from the Gadsden Purchase which had opened southeastern Arizona to extensive prospecting and settlement.

Economic collapse came swiftly after 1918 when major mining operations ceased, triggering population exodus, business closures, and the town’s eventual transformation into the ghost town you see today.

Mining Boom Years

The economic transformation of Duquesne began in earnest during 1890 when George Westinghouse acquired the majority of Patagonia mining claims and established the Duquesne Mining & Reduction Company. This Pittsburgh-based venture revolutionized local mining techniques, evolving from rudimentary methods to industrial-scale operations.

Between 1912 and 1918, you’d have witnessed Duquesne’s golden era, when advanced mining techniques extracted high-yield ore averaging 6% zinc, 3% lead, 3% copper, and 6 oz. silver per ton.

The economic impacts were profound:

- Population surged to approximately 1,000 residents

- Infrastructure expanded with commercial buildings and services

- Employment opportunities flourished across multiple sectors

- Regional trade networks strengthened, particularly with Mexico

This prosperity wouldn’t last forever. As mineral reserves diminished and market conditions shifted, Duquesne’s boom years gradually gave way to economic contraction.

Post-War Economic Decline

Following World War I, Duquesne’s once-thriving economy collapsed under the weight of plummeting copper demand, triggering a rapid unwinding of the community’s industrial base.

You’d hardly recognize the bustling mining town that had produced over 450,000 tons of ore during its 1912-1918 peak years.

The economic repercussions cascaded through every aspect of local life. The Duquesne Reduction Plant shut down, the post office closed by 1920, and businesses that had served miners and their families disappeared.

Railroad service—the lifeline of mineral transport—eventually ceased by 1962, permanently severing essential commercial connections.

Despite attempts at community resilience, population numbers dwindled from approximately 1,000 to mere handfuls by the 1920s, transforming this once-vibrant industrial hub into the ghost town you’d find today.

Between Two Countries: Border Influences

Situated less than five miles from the U.S.-Mexico border, Duquesne’s development and history were fundamentally shaped by its international borderland status.

The town’s economic life thrived on cross-border trade as materials, mining technology, and possibly labor flowed between Arizona and Sonora. Cultural exchanges inevitably occurred as American industrialists and likely Mexican workers interacted in this remote Patagonian mountain outpost.

The border’s influence manifested in four key ways:

- Ancient trails connecting mining regions on both sides became corridors of commerce.

- Washington Camp served as a supply hub for communities straddling the international line.

- Shared mining traditions and technologies crossed political boundaries.

- Economic fortunes rose and fell simultaneously with neighboring Mexican mining towns.

Preservation Efforts and Current Ownership

You’ll find limited active restoration happening in Duquesne today, as most of the ghost town exists on private property with visible “No Trespassing” signs that must be respected.

The Victorian frame house once owned by George Westinghouse stands in ruins alongside a few surviving structures including a large boarding house, a smaller frame house, and an adobe commercial building.

When exploring the area’s mining history, remember to observe property boundaries, as the current residents maintain legal ownership rights that restrict public access to these historically significant remains.

Recent Restoration Projects

After decades of decline, Duquesne has recently entered a new chapter in its history with the acquisition by private owners who’ve initiated extensive restoration efforts throughout the ghost town.

These restoration techniques focus on maintaining historical accuracy while stabilizing the town’s remaining structures.

The current restoration priorities include:

- Structural repairs and roof replacements on the boarding house and adobe commercial building

- Foundation reinforcement for unstable historic structures

- Preservation of the schoolhouse and bar/brothel with authentic period details

- Stabilization of the Westinghouse estate ruins and mining equipment

Though the new owners remain private, their commitment to preserving Duquesne’s mining-era legacy is evident.

Their methodical approach prioritizes authenticity, ensuring these historical treasures will educate future generations about Arizona’s mining past.

You’ll eventually see the results when they open for historical tours.

Private Property Rules

While restoration efforts in Duquesne show promise, visitors should be aware that the ghost town exists under strict private property regulations that fundamentally shape its preservation.

You’ll encounter “no trespassing” signs throughout the area, as Duquesne and neighboring Washington Camp remain privately owned by a small group of inhabitants who actively patrol against unauthorized entry.

Public roads may wind through town, but access limitations prohibit exploration of structures and mine sites without explicit permission from owners.

These property rights create significant challenges for preservation work—historic buildings continue deteriorating with minimal intervention, as owners maintain final authority over all structures.

Unlike some Arizona ghost towns managed by federal agencies, Duquesne’s private status means no organized volunteer preservation occurs and most historic preservation grants remain inaccessible.

Neighboring Ghost Towns of the Patagonia Mountains

The Patagonia Mountains region of Southern Arizona harbors a remarkable cluster of ghost towns that once thrived during the mineral booms of the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

The untamed wilderness of Southern Arizona conceals forgotten settlements, monuments to prosperity’s fleeting nature in America’s mining frontier.

While exploring Duquesne, you’re positioned within a fascinating network of abandoned settlements tied to mining history.

Nearby ghost towns worth investigating include:

- Harshaw – Founded in the 1870s with Harshaw history showcasing a once-thriving mile-long main street

- Ruby – Accessible for Ruby exploration with preserved jail, school, and mining structures (permit required)

- Pearce – Features remnants of commerce including general stores and a historic cemetery

- Gleeson and Courtland – Contain restored buildings and mining artifacts from their copper and silver heyday

These settlements form an extensive tableau of the boom-and-bust cycle that defined Arizona’s mining frontier.

Photography Tips for Capturing Duquesne’s History

Capturing Duquesne’s weathered remnants requires both technical skill and historical sensitivity to document this once-thriving mining community.

Respect property boundaries by shooting from public roads—telephoto lenses and drones can bridge the distance while avoiding trespassing issues.

The Victorian-style Westinghouse home, adobe commercial buildings, and boarding house create powerful historical narratives when photographed in early morning or late afternoon light.

Focus on architectural details and weathered textures to convey the passage of time.

For more atmospheric shots that might suggest ghostly encounters, incorporate the cemetery, mine tailings, and abandoned shafts.

Wide-angle compositions establish context while close-ups of rusted metal and peeling paint tell intimate stories of Duquesne’s boom-and-bust cycle.

Always leave artifacts undisturbed, preserving the site’s integrity for future explorers.

Frequently Asked Questions

Were Apache Attacks on Miners Documented in Specific Incidents?

Shadows of bloodshed remain documented: you’ll find specific incidents of Apache raids recorded, including John’s 1861 death, Mowry’s destruction, and Mexican prospectors’ 1879 attack. Miner’s accounts detail these violent encounters.

What Happened to Residents When the Mines Closed?

You faced immediate unemployment as mining ceased in 1918, triggering widespread community relocation. You’d find your neighbors dispersing to other mining towns or cities, fleeing the economic decline that hollowed Duquesne.

Was Duquesne Involved in Prohibition-Era Smuggling Across the Border?

Like a dying ember refusing to reveal its former glow, you’ll find no concrete evidence of bootlegging routes through Duquesne. Its border proximity suggests potential involvement, but historical records document no specific border conflicts regarding smuggling.

Did Any Famous Outlaws Visit or Hide in Duquesne?

You won’t find outlaw legends or notorious criminals in Duquesne’s historical record. Despite its remote location, the town’s industrial mining operation and company management likely deterred famous outlaws from visiting.

Are There Reported Ghost Sightings or Paranormal Activity?

You won’t find documented ghost stories at Duquesne. Unlike Arizona’s famous haunted locations, historical records reveal no specific paranormal activity reports. The private property status severely limits paranormal investigations and visitor experiences.

References

- https://azoffroad.net/washington-campduquesne

- https://kids.kiddle.co/Duquesne

- https://www.gvrhc.org/Library/GhostTowns.pdf

- https://www.mindat.org/loc-3384.html

- https://www.legendsofamerica.com/az-patagoniaghosts/

- https://www.visitskyislands.com/ghost-towns-of-harshaw-mowry-washington-camp-and-duquesne/

- https://www.visittucson.org/listing/ghost-towns-of-harshaw-mowry-washington-camp-and-duquesne/6299/

- https://www.ghosttowns.com/states/az/duquesne.html

- https://south32hermosa.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/Patagonia-Mining-History.pdf

- https://santacruzheritage.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Mining-Booms-1.pdf