Stanwix Station began as Flap Jack Ranch before becoming an essential Butterfield Overland Mail stop 80 miles east of Fort Yuma. You’ll find historical significance in its thick-walled station that witnessed the Civil War‘s westernmost skirmish on March 30, 1862, when Confederate Rangers battled Union troops. Though now a ghost town, archaeological excavations have revealed thousands of years of human activity, including prehistoric irrigation systems and Civil War artifacts. The desert outpost’s story continues beyond its abandoned walls.

Key Takeaways

- Stanwix Station began as Flap Jack Ranch before becoming a crucial Butterfield Overland Mail stop with protective stone walls against Apache threats.

- The site witnessed the westernmost skirmish of the American Civil War on March 30, 1862, between Confederate Rangers and Union troops.

- Archaeological investigations revealed artifacts spanning thousands of years, including Civil War remnants and prehistoric irrigation systems.

- Located 80 miles east of Fort Yuma, the station provided essential water access in the desert for travelers and military operations.

- Now a ghost town, Stanwix Station’s preservation faces challenges including water shortages and construction projects threatening its historical significance.

From Flap Jack Ranch to Stanwix: The Evolution of a Desert Outpost

As Arizona Territory expanded throughout the mid-19th century, remote outposts emerged along critical transportation corridors to support the movement of people, goods, and information across the harsh desert landscape.

Flap Jack Ranch represents the earliest iteration of what would become Stanwix Station. Initially developed as an agricultural operation along the Gila River, it gradually transformed into an essential transportation hub.

You’ll find its strategic positioning—approximately 80 miles east of Fort Yuma—was no accident. The site offered precious water access in an otherwise unforgiving environment.

When Butterfield Overland Mail established its route in the 1850s, the ranch’s purpose evolved. Simple buildings gave way to dedicated structures for passengers, stock animals, and supplies.

This ranch development mirrored the territory’s growth, transforming from isolated homestead to critical infrastructure within America’s expanding frontier. The site gained historical significance in 1862 when it became the location of the westernmost fight of the American Civil War. The brief engagement between Union and Confederate forces resulted in the burning of hay intended for Union animals, which slowed the California Column’s advance.

Life at the Butterfield Overland Stage Stop (1858-1861)

When the Butterfield Overland Mail Company established operations at Stanwix Station in 1858, it marked the beginning of a brief but significant chapter in America’s first transcontinental mail service.

The station’s thick stone walls, rising 8-10 feet tall, provided essential protection for employees facing Apache threats in this remote desert outpost.

Stone fortifications stood between frontier postal workers and the deadly dangers of Apache territory

Stagecoach life at Stanwix centered around supporting the 24-day journey between San Francisco and St. Louis.

Wild mules pulled specialized Concord spring wagons across the harsh terrain, while staff maintained the critical infrastructure that kept America connected.

The station’s practical design allocated two-thirds of its space to animal corrals, with the remainder serving as quarters for weary personnel.

Desert challenges were constant, from violent incidents like the September 1858 attack at Dragoon Springs to the relentless environmental demands of Arizona’s Gila River region.

The company’s experienced founder John Butterfield Sr. brought 37 years of stage line operations experience to the venture, ensuring the station’s critical role in the longest mail contract in U.S. history.

The station operated until March 1861 when the Civil War caused the discontinuation of the Butterfield Overland Mail service along the southern route.

The Westernmost Battle of the Civil War

When you visit Stanwix Station today, you’re standing at the site of the American Civil War‘s westernmost battle, a brief but significant engagement that occurred on March 30, 1862.

Here, Captain Hunter’s outnumbered Confederate Rangers successfully delayed Captain Calloway’s 272 Union troops of the California Column, demonstrating the effectiveness of cavalry tactics in desert warfare. The Rangers burned Union supplies at the station, seriously disrupting Colonel Carleton’s carefully planned march toward Tucson.

The Confederate presence at this remote desert outpost marked their furthest western advance during the conflict, representing a remarkable projection of military power across the harsh Arizona Territory. The skirmish involved only 10 Confederate soldiers against the much larger Union force, showcasing the strategic importance of even small-scale operations.

Forgotten Desert Skirmish

The arid desert landscape of western Arizona became an unlikely theater of Civil War conflict on March 30, 1862, when a brief but significant skirmish erupted at Stanwix Station.

You’ll find little mention of this forgotten history in most Civil War accounts, yet it represents the westernmost armed engagement of the entire conflict.

Captain William P. Calloway’s 272 Union troops from the California Column encountered Confederate Arizona Rangers posing as civilians.

When the Rangers ordered Union sentinels to surrender, the outnumbered guards fled under fire, resulting in one Union casualty.

The Confederates burned supplies and disrupted communications before disappearing into the desert terrain.

Despite Union cavalry’s pursuit, the Rangers escaped.

This brief desert warfare episode delayed but couldn’t prevent the Union’s eventual capture of Tucson, leaving Stanwix Station to fade into historical obscurity.

Confederates’ Furthest West

Stanwix Station’s historical significance extends far beyond its humble adobe walls, marking the geographical limit of Confederate military reach during the Civil War.

On March 30, 1862, Captain Sherod Hunter’s Texas Rangers clashed with Captain William Calloway’s 272 Union cavalrymen from the California Column.

You’ll find Confederate strategies on full display here—guerrilla tactics and ambush attempts designed to disrupt Union supply lines 80 miles west of their stronghold at White’s Mill.

Union tactics focused on securing the Southwest corridor and protecting crucial California resources. The skirmish involved approximately 20 Confederate soldiers and 25 Union troops. During this skirmish, one Union soldier, Private William Semmilrogge, was wounded but later recovered from his injuries.

This brief skirmish, though resulting in minimal casualties, effectively ended Southern military presence in the far West.

When you visit this remote desert location, you’re standing on the westernmost battleground of America’s deadliest conflict.

Confederate Rangers vs. California Column: The Military Encounter

During the spring of 1862, two military forces clashed in the remote Arizona desert, setting the stage for a series of encounters that would determine the region’s fate during the Civil War.

At Stanwix Station along the Gila River, Confederate Arizona Rangers under Captain Sherod Hunter first engaged Union scouts on March 30. Their military tactics included burning hay reserves and capturing Captain McCleave, effectively delaying the California Column’s advance. This bought time for Confederate preparations at Picacho Pass. This military engagement represents part of the Civil War’s reach that extended beyond traditional battlefields into the Arizona territory.

The Confederate Rangers’ tactical approach—burning supplies and capturing key personnel—demonstrated their mastery of delaying warfare despite limited resources.

The cavalry engagement at Picacho Pass on April 15 saw Lt. Barrett’s unauthorized attack against Sgt. Holmes’ Rangers. Despite lasting only 90 minutes, the skirmish claimed Barrett’s life and further stalled Union progress. Colonel James Carleton had insisted on proper desert uniforms for his troops to withstand the harsh climate they would face.

Though outnumbered by Colonel Carleton’s professional force of 1,400-2,350 men, Hunter’s guerrilla-style operations successfully disrupted Union logistics before ultimately retreating to Texas.

Strategic Importance in the Far Western Theater

When you examine Stanwix Station‘s position on the map, you’ll recognize it as a critical desert supply corridor that controlled water and forage access in an otherwise hostile environment.

The station’s strategic location 80 miles east of the California border transformed it into a Union-Confederate flashpoint where Confederate forces burned hay supplies to delay the California Column’s advance.

Control of such waypoints proved decisive for Western Campaign logistics, as these stations dictated military movement patterns and ultimately influenced the sequence of battles throughout the Arizona theater.

Desert Supply Corridor

Stretching across the sun-drenched landscapes of Arizona, the Desert Supply Corridor served as an essential artery in the Far Western Theater‘s logistical network. This critical desert transportation route connected Phoenix and Tucson within the Sun Corridor megapolitan area, extending from the U.S.-Mexico border northward to Prescott.

When you explore the region’s history, you’ll find the corridor played four crucial roles:

- Supported aerospace and defense manufacturing relocated inland during WWII

- Connected desert communities to larger supply chain hubs and ports of entry

- Provided high-speed alternative routes linking desert towns to Mexico

- Integrated urban and rural economies across the Intermountain West

This infrastructure balanced economic development with conservation of over one million acres of Sonoran Desert, ensuring freedom of movement while preserving natural landscapes.

Union-Confederate Flashpoint

Though often overlooked in Civil War historiography, Stanwix Station emerged as a vital flashpoint in the Far Western Theater on March 29, 1862, when Captain William P. Calloway‘s 272 Union troops encountered Confederate pickets.

This brief engagement—the westernmost Civil War battle—marked the opening clash of the California Column‘s ambitious 900-mile campaign.

You’re standing at what was once a vital chokepoint in Arizona history, where military tactics played a decisive role. The Confederates’ destruction of hay supplies and strategic placement of pickets delayed Union advances, providing rebels valuable time to prepare defenses.

Despite being a small skirmish, this encounter triggered escalating engagements throughout the territory. The Union victory here initiated the successful expulsion of Confederate forces from Arizona, effectively eliminating Southern presence in the Far West.

Western Campaign Logistics

As the California Column prepared for its ambitious 900-mile expedition through unforgiving desert terrain, control of the Butterfield Overland Mail route stations became the decisive factor in the Far Western Theater’s logistical battle.

You’re witnessing a campaign where resource management dictated military strategy—not simply troop movements.

The logistics challenges faced by both sides reveal why Stanwix Station proved so vital:

- Confederate forces deliberately burned hay stores to delay Union advancement, buying essential time for defensive preparations

- Water and forage scarcity concentrated military operations around established supply nodes

- The 2,350 California volunteers required meticulously planned water conservation tactics

- Station control determined operational tempo in a theater where alternative routes were virtually nonexistent

This warfare of resources exemplified how desert campaigns hinged on controlling supply points rather than traditional battlefield dominance.

Buffalo Bill’s Connection to the Ghost Town

While many associate Buffalo Bill with Wild West shows and frontier entertainment, his business ventures extended deep into Arizona’s mining sector during the late 19th century.

His reorganization of Campo Bonito into the Cody-Dyer Arizona Mining & Milling Company represented a significant $5 million investment near the Stanwix area.

Buffalo Bill transformed Campo Bonito into a $5 million mining venture, reshaping Arizona’s commercial landscape.

Buffalo Bill’s ventures aligned perfectly with Arizona’s territorial development, establishing corporate presence amid the ghost town landscape. The Cody name attracted investors to the region, transforming the area from military outposts to commercial enterprises.

His mining operations symbolized the shift from frontier commerce to organized corporate structures that defined post-Civil War economic expansion.

You’ll find evidence of Buffalo Bill’s legacy in territorial archives, documenting how celebrity entrepreneurship influenced the development of ghost town regions throughout western Arizona.

Archaeological Discoveries and Physical Remains

The archaeological landscape of Stanwix Station reveals far more than Buffalo Bill’s business ventures in Arizona’s territorial period.

As you explore this desert ghost town, you’ll discover evidence spanning thousands of years of human activity preserved in the volcanic terrain and desert pavements.

Archaeological investigations have uncovered:

- Projectile points including Folsom points (8900-8200 B.C.) and San Pedro points

- Remnants of prehistoric irrigation systems including ancient canals up to 8 feet deep

- Military artifacts from the westernmost Civil War skirmish on March 29, 1862

- Domestic items including charred corn, pottery fragments, and stone tools

The Great Bend of the Gila cultural landscape continues to yield discoveries, with petroglyphs, agricultural implements, and evidence of trade networks all protected under federal preservation standards.

Visiting Stanwix Station Today: What Survives

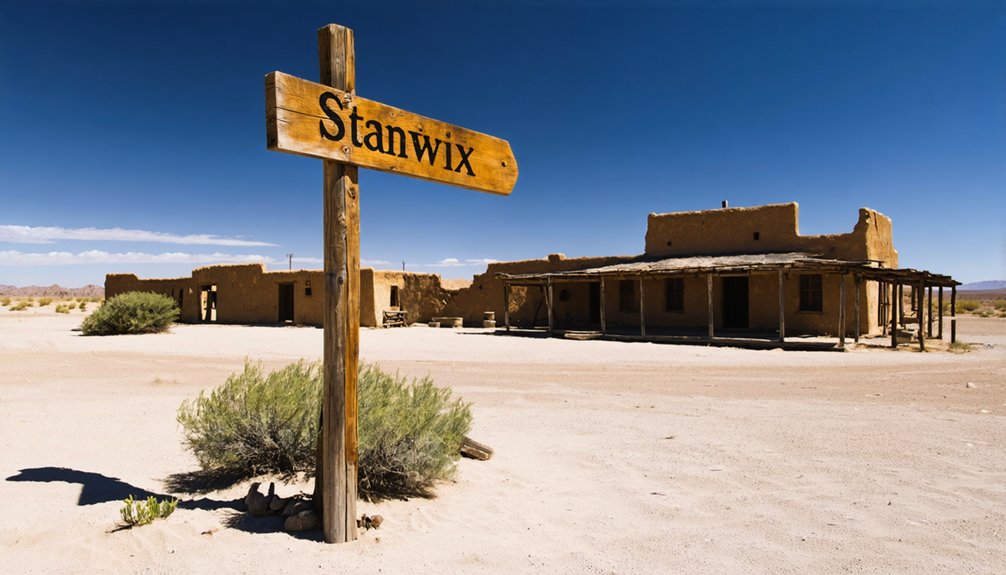

Visitors approaching Stanwix Station today will find a stark contrast to the once-bustling desert outpost of the 1800s. Only scattered stone and adobe foundations remain, with occasional wooden posts marking where structures once stood. The historical remnants are minimal, with no intact buildings surviving the harsh desert conditions.

You’ll encounter no formal markers, interpretive signs, or visitor facilities at Stanwix Station. The remote location in Yuma County requires high-clearance vehicles to navigate unpaved desert roads. Cell service is limited, and no amenities exist nearby.

Desert exploration here offers solitude and connection to the past, but prepare accordingly. Bring water, inform others of your plans, and visit during daylight.

While on public land, it’s wise to verify current access regulations before your journey.

Preserving Arizona’s Forgotten Civil War Heritage

Despite its significant role in westernmost Civil War conflicts, Arizona’s battlefield heritage remains largely overlooked in national historical narratives. The American Battlefield Trust works to protect sites like Picacho Peak, where the westernmost fatal skirmish occurred in 1862.

These preservation efforts face substantial challenges due to the region’s unique characteristics.

- Archaeological sites suffer from natural deterioration and limited funding

- Remote locations like Stanwix Station present logistical difficulties for heritage preservation

- Water shortages and construction projects temporarily restrict preservation activities

- Fragmented historical sites complicate cohesive interpretation of their historical significance

Living History events at preserved locations offer experiential engagement, fostering community stewardship while educating visitors about Arizona’s complex Civil War history—a critical approach to maintaining these threatened western frontiers of American history.

Frequently Asked Questions

Did Any Famous Gunfighters or Outlaws Ever Visit Stanwix Station?

You’ll find no confirmed records of famous gunfighters or notorious outlaws visiting Stanwix Station. Buffalo Bill’s 1902 carving represents the only documented evidence of a well-known frontier personality’s presence there.

What Happened to the Original Station Owners After the Civil War?

Like desert dust scattered by wartime winds, your question reaches beyond available records. Historical documentation doesn’t reveal what happened to the original Stanwix Station owners after the Civil War’s conclusion. Their Station Legacy remains untraced.

Were There Any Indigenous Encounters or Conflicts at Stanwix Station?

Yes, you’ll find Apache and Yavapai tribes conducted raids on Stanwix Station, targeting this strategic Butterfield Overland Stage stop. These historical conflicts prompted military responses from Arizona Volunteers defending frontier transportation routes.

What Temperatures and Weather Conditions Did Travelers Typically Endure?

You’d face a harsh desert climate with temperature extremes of 87°F summer days and 49°F winter nights, low humidity, scarce rainfall, and potential dust storms requiring constant adaptation.

Did Any Women or Families Permanently Reside at Stanwix Station?

In desert’s barren embrace, you’ll find no evidence of family life at this outpost. Historical records show no women settlers or permanent families resided there—only military personnel and transient male workers occupied the station.

References

- https://edgeinducedcohesion.blog/2012/03/03/arizona-a-forgotten-theater-of-the-civil-war/

- https://beyond.nvexpeditions.com/arizona/yuma/stanwix.php

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zNsGNbsIQSc

- https://www.battlefields.org/learn/articles/clash-picacho-peak

- https://military-history.fandom.com/wiki/Battle_of_Stanwix_Station

- https://hikearizona.com/decoder.php?ZTN=19694

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Stanwix_Station

- https://kids.kiddle.co/Battle_of_Stanwix_Station

- https://civilwar-history.fandom.com/wiki/Stanwix_Station

- https://www.archaeologysouthwest.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/GreatBend.pdf