You’ll find Ballarat Ghost Town nestled in south-central Inyo County, California, where this once-bustling mining supply hub served the lucrative Panamint Range from 1897 until its decline in the early 1900s. With its seven saloons, three hotels, and vibrant community of 400-500 residents, Ballarat thrived during the Ratcliff Mine’s peak operations. The town’s adobe ruins and foundations now stand as silent witnesses to a fascinating chapter of California’s mining history that beckons further exploration.

Key Takeaways

- Ballarat became a ghost town by 1917 following the closure of the Ratcliff Mine and subsequent economic decline in the early 1900s.

- Located in California’s Panamint Valley, Ballarat served as a vital supply hub for nearby mines with a peak population of 400-500 residents.

- The town featured seven saloons, three hotels, and essential services including a post office, school, and Wells Fargo station.

- Adobe brick structures and building foundations remain visible today, preserving the architectural heritage of this abandoned mining community.

- Extreme desert conditions, water scarcity, and the depletion of precious metals contributed to the town’s ultimate abandonment.

The Rise of a Desert Mining Hub

While many mining towns emerged across California during the late 19th century, Ballarat distinguished itself as an important desert hub after its 1897 establishment in south-central Inyo County. Named after Australia’s famous gold district, you’ll find it positioned strategically at the Panamint Range’s western flank, serving as a significant supply point for surrounding mining operations.

The town’s rapid growth reflected sophisticated mining techniques at operations like the Ratcliff Mine, which extracted 15,000 tons of gold ore between 1898 and 1903. The area’s rich quartz vein deposits made sustained mining operations possible for decades. A bustling Wells Fargo Station operated in town, facilitating banking and mail services for the mining community.

Community resilience shaped Ballarat’s expansion to 500 residents by 1898, despite the harsh desert environment. You’ll appreciate how the town’s infrastructure grew to include hotels, saloons, a post office, and necessary services, making it an important jumping-off point for prospectors venturing into the unforgiving Mojave Desert’s mining districts.

From Gold Rush Dreams to Ghost Town Reality

Despite Ballarat’s promising start as a desert mining hub, its fate began to shift dramatically after 1905 when the closure of the Ratcliff Mine triggered a cascade of economic decline.

The shuttering of Ratcliff Mine in 1905 marked the beginning of the end for Ballarat, as prosperity gave way to decline.

You’d have witnessed the gold rush community dynamics unravel as nearby mining districts faltered, causing the town’s essential role as a supply center to diminish.

The town’s infrastructure, which once boasted three hotels and seven saloons, couldn’t sustain itself without the steady flow of prospectors.

Much like the historic Eureka Rebellion miners, the residents of Ballarat fought against challenging circumstances, though their struggle was ultimately against the harsh realities of dwindling gold deposits rather than government opposition.

By 1917, the closure of the post office signaled Ballarat’s transformation into a ghost town.

The harsh desert environment, combined with the area’s lawlessness and lack of economic diversity, sealed its fate.

Today, you’ll find only adobe ruins where meek-eyed burros once shared streets with hopeful miners, a reflection of the fleeting nature of desert mining dreams.

The legendary prospector Shorty Harris remained one of the town’s last residents, staying until shortly before his death in 1934.

Life in the Wild Panamint Valley

Life in California’s Panamint Valley tested the limits of human endurance against nature’s harshest elements. You’d find yourself battling extreme temperatures that soared to 120°F in summer, while winters brought bitter cold to the rugged desert landscape.

Despite isolation challenges, a resilient community of 400-500 residents forged ahead, establishing schools, hotels, and saloons around the Radcliffe Mine operations. The mine became profitable after timbers and machinery were transported from nearby Randsburg. The town was established in 1896 during a significant gold mining boom.

Community resilience showed in their ability to maintain lengthy supply chains, hauling essential goods by burro across treacherous terrain from distant locations. At Post Office Spring, you’d collect mail from an improvised box, while Wells Fargo’s presence kept crucial communication lines open.

Daily life revolved around the mining rhythm, with social gatherings in saloons offering brief respite from the unforgiving environment that shaped every aspect of existence.

Notable Characters and Desert Legends

Throughout Ballarat’s storied history, three legendary figures emerged as the embodiments of desert resilience and frontier independence.

You’ll find Seldom Seen Slim, who lived alone until 1968, representing the ultimate desert eccentric. Shorty Harris, the persistent prospector who struck rich mineral claims, exemplified the tenacious spirit that drove men to search these harsh lands. The town’s seven saloons regularly hosted these characters. The presence of Jim Sherlock, a Wyoming gunman, added to Ballarat’s reputation as a haven for those seeking escape from civilization.

These Prospector Legends have left their mark on the ghost town‘s identity, drawing modern visitors who sense their ghostly echoes in the ruins and cemetery. His infamous claim of not bathing for 20 years due to water scarcity became part of local lore.

Their stories, preserved through oral histories and Blair’s musical tribute to Slim, continue to define Ballarat as a symbol of untamed freedom in California’s mining frontier.

Architecture and Infrastructure Through Time

When you examine Ballarat’s architectural heritage, you’ll find that adobe brick construction dominated the townscape, providing natural insulation against the harsh desert climate.

The town’s utilitarian structures, including hotels, saloons, and civic buildings, reflected frontier pragmatism with minimal ornamentation and functional designs. Among these structures was the jail and morgue building which remains one of the most well-preserved structures today.

Today, the weathered adobe ruins and foundations stand as evidence to these early construction methods, while a 1960s cinder block general store represents the town’s brief attempted revival.

Original Building Materials

The sun-baked adobe bricks of Ballarat’s original structures tell a story of pragmatic frontier construction.

You’ll find these locally-sourced clay blocks formed the foundation of essential buildings, from the Wells Fargo station to the jail-morgue complex. Adobe’s natural insulation kept interiors cool during scorching days and warm through desert nights.

Weathered timber complemented the adobe, providing vital framing and finishing elements for miners’ cabins and support buildings. Preservation efforts continue to reinforce remaining walls against further deterioration.

While the 1960s brought attempts at modernization with cinder block construction and electrical hookups, these later additions couldn’t match the historical significance of the original materials.

Today, you’ll witness the gradual structural decay of these functional materials – adobe walls crumbling under harsh desert conditions and wooden elements reduced to skeletal remains, preserving only fragments of Ballarat’s mining-era architecture.

Architectural Design Elements

Life in Ballarat revolved around its strategically planned layout, with commercial structures concentrated in the heart of the settlement.

You’ll find the town’s seven saloons and three hotels clustered together, maximizing accessibility for miners and travelers. The utilitarian buildings, constructed primarily of adobe bricks, reflected the practical needs of this rugged mining community.

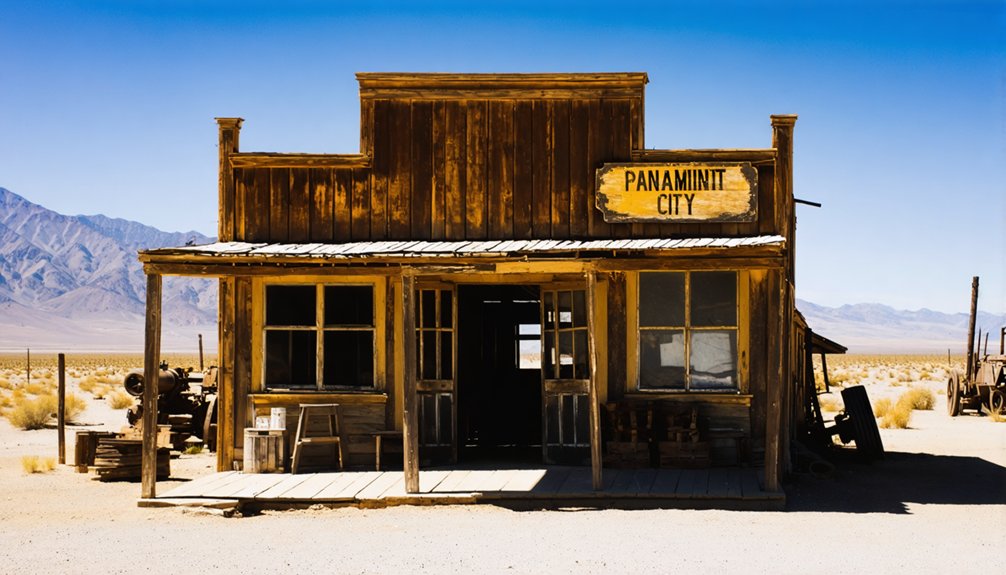

The architectural design emphasized functionality over aesthetics, featuring simple one- to two-story rectangular structures with flat or gently sloping roofs suited to desert conditions.

Many commercial buildings sported false fronts, a classic Old West feature that gave the impression of larger, more established structures.

Crucial services, including the Wells Fargo station, post office, school, jail, and morgue, were thoughtfully positioned throughout the town, creating an efficient flow of daily activities around the essential Post Office Springs water source.

Structural Ruins Today

Modern visitors to Ballarat encounter a haunting collection of deteriorating adobe and wooden structures that chronicle the town’s gradual decay.

You’ll find adobe buildings slowly returning to the earth, their walls succumbing to wind and rain erosion, while weathered wooden shacks display missing walls and warped siding.

The jail stands as one of the few original structures, though time hasn’t been kind to its walls.

Near the maintained general store/museum, you’ll spot foundations of former hotels, saloons, and the school.

The site’s infrastructure remains visible through cement foundations, old roads, and water cisterns.

A 1942 Dodge power wagon with its mysterious pentagram adds to the ghost town’s intrigue, while mining remnants – tunnels, prospect holes, and mill foundations – remind you of Ballarat’s industrial past.

The Australian Connection

During California’s mining era, Australian immigrant George Riggins established a meaningful connection between two gold rush communities by naming the new settlement after his hometown of Ballarat, Victoria.

This deliberate choice created a lasting link to Australia’s rich mining legacy, connecting two significant gold rush histories across the Pacific.

You’ll find this Australian heritage woven into the town’s identity, reflecting the global nature of 19th-century mining culture.

The naming wasn’t merely coincidental – Ballarat, Victoria had already achieved fame as a prosperous gold rush center by 1851, decades before its California namesake emerged in 1897.

Through Riggins’ influence, the town’s identity became intertwined with the Australian gold fields, creating a unique historical bridge that continues to intrigue visitors and historians today.

Entertainment and Social Life in the Old West

While miners toiled in the harsh desert conditions, Ballarat’s vibrant social scene centered around its seven saloons, where workers sought refuge and entertainment after long days of prospecting.

You’d find social gatherings teeming with painted ladies, gambling tables, and the sounds of miners sharing tales of their latest strikes. The Wells Fargo station served as a hub for communication, while three hotels accommodated the steady stream of travelers and transient workers.

Mining camaraderie flourished in this “wild and woolly” atmosphere, where legendary figures like “Seldom Seen Slim” and Frank “Shorty” Harris became part of local lore.

Without churches but plenty of whiskey, the town’s entertainment focused on immediate pleasures rather than formal institutions. This work-hard, play-hard culture defined Ballarat’s peak years, when 400 to 500 residents called this desert oasis home.

Modern-Day Adventures and Tourism

Today’s adventurous travelers can discover Ballarat ghost town via a 3-mile dirt road off Death Valley National Park, where the stark remnants of California’s mining era await exploration.

Step into California’s mining past at Ballarat ghost town, where desert winds whisper tales through weathered ruins off Death Valley.

You’ll find the site most accessible during spring and fall mornings when temperatures remain manageable for desert exploration.

The town offers diverse activities including four-wheeling adventures, photography opportunities of the Panamint Valley’s dramatic vistas, and hiking through historical ruins.

You can explore the Pleasant Canyon Loop Trail‘s 27-mile route to discover old mining camps, or visit the General Store & Museum to examine local artifacts.

While amenities are limited, you’ll find basic supplies at the store, though it’s essential to bring plenty of water.

The cemetery, featuring “Seldom Seen Slim’s” grave, provides a tangible connection to the region’s mining heritage.

Mining Operations and Economic Impact

You’ll find Ballarat’s origins rooted in its role as a crucial supply hub for the Panamint Mountain Range mines, where it supported extensive mining activities in nearby canyons from 1897 onward.

The town’s peak mining years centered around the Radcliffe Mine, which produced 15,000 tons of gold ore between 1898 and 1903, while supporting a population of 500 residents with seven saloons, three hotels, and various essential services.

The closure of the Radcliffe Mine in 1905 triggered Ballarat’s economic decline, leading to the town’s eventual abandonment and its transformation into the ghost town you can visit today.

Gold Rush Supply Hub

During the height of the Death Valley mining era, Ballarat established itself as an indispensable supply hub for prospectors venturing into the harsh Panamint Range.

You’d find essential Ballarat supplies and mining equipment at the town’s bustling general store, while Wells Fargo provided vital financial services for your mining operations.

The town’s strategic location made it your gateway to fortune, offering:

- Complete outfitting services for prospectors heading into remote mining districts

- Water and provisions necessary for extended stays in the unforgiving desert

- Communication services through the post office to maintain connections with the outside world

With a peak population of 500 residents, Ballarat’s economy thrived on supporting both independent prospectors and larger mining companies, providing everything from basic tools to thorough mining supplies.

Peak Mining Production Years

The Ratcliff Mine’s discovery in 1897 ignited Ballarat’s most prolific era of mineral extraction, transforming the supply hub into a powerhouse of gold production.

You’ll find that mining technology during this period focused on extracting gold from complex quartz veins embedded in metamorphic rock, with production techniques centered on crushing ore and separating precious metals from sulfide minerals.

During its first six years, the Ratcliff Mine processed approximately 15,000 tons of ore, yielding between $300,000 and $1 million in gold.

The mining boom attracted hundreds of prospectors, swelling Ballarat’s population to 500 residents.

This prosperity wouldn’t last – by 1905, declining yields led to reduced operations.

While sporadic mining continued until 1959, the town’s golden age effectively ended when the Ratcliff Mine scaled back production in 1905.

Economic Decline Pattern

When the Ratcliff Mine ceased operations in 1905, Ballarat’s economic fabric began unraveling at an accelerating pace.

You’ll notice how the town’s economic resilience quickly diminished as nearby mines followed suit, creating a domino effect that crippled the local economy. The harsh desert conditions and remote location left little room for community adaptation, forcing businesses to shutter and families to relocate.

- Mining operations declined sharply due to exhausted gold veins and lack of infrastructure investment.

- Local businesses, including hotels, saloons, and the post office, closed as population dropped from 500 to nearly zero.

- Transportation costs and extreme weather conditions prevented alternative industries from taking root.

The town’s isolation and dependence on mining meant that once the precious metal wealth dried up, there wasn’t a viable path to economic recovery.

Desert Survival: Water Sources and Climate

Surviving in Ballarat’s unforgiving desert environment demands thorough understanding of its extreme climate patterns and limited water sources.

You’ll face temperatures soaring to 120°F during 14.5-hour summer days, while winter nights can plunge to 30°F, requiring advanced desert adaptation strategies.

Post Office Springs, located quarter-mile south, remains the area’s primary water source since the 1850s.

Your survival depends on smart water conservation techniques. You must carry sufficient water supplies, as there’s no modern infrastructure.

The harsh conditions demand protection against both heat exhaustion and hypothermia. Afternoon winds intensify the environment’s challenges, affecting camp setup and fire management.

When exploring this ghost town, you’re confronting the same water scarcity that ultimately led to its abandonment in the early 1900s.

Frequently Asked Questions

Are There Any Dangerous Animals or Snakes Around Ballarat Today?

Slithering sidewinders and Mojave rattlers remain your primary wildlife encounter risks. You’ll need to watch for these venomous snake species, especially during warmer months when they’re most active.

Can Visitors Take Artifacts or Materials From the Abandoned Buildings?

No, you can’t remove artifacts or materials. They’re protected by private property laws and hold essential historical significance. Taking items damages artifact preservation and diminishes the site’s authentic heritage for future visitors.

Is Special Permission Required to Visit or Photograph the Ghost Town?

Under the vast desert sky, you don’t need special permission to visit or photograph Ballarat’s public areas. While there aren’t formal visitor guidelines or photography regulations, respect private property boundaries.

What Happened to the Bodies Buried in Ballarat’s Cemetery?

You’ll find the original burials remain undisturbed in their graves today, with no documented grave relocation occurring. The cemetery’s preserved state includes “Seldom Seen Slim’s” 1968 burial, the last recorded interment.

Does Anyone Maintain Legal Ownership of the Remaining Structures?

You’ll find the ghost town’s structures remain under private ownership, though specific details aren’t publicly documented. While owners allow visitor access, there’s no formal historical preservation authority controlling the buildings.

References

- http://www.backcountryexplorers.com/ballarat-ghost-town.html

- https://www.legendsofamerica.com/ca-ballarat/

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GDpsq09tkrA

- https://www.atlasobscura.com/places/ballarat-ghost-town

- https://www.desertusa.com/desert-california/ballarat.html

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ballarat

- https://digital-desert.com/ballarat/

- https://westernmininghistory.com/library/452/page1/

- https://westernmininghistory.com/towns/california/ballarat/

- https://www.mindat.org/loc-209250.html