You’ll find Benton’s ghostly remains 11 miles east of Rawlins, Wyoming, where this notorious “Hell on Wheels” railroad town flourished briefly in 1868. During its three-month existence, the settlement of 3,000 people earned its reputation as Wyoming Territory’s deadliest frontier town, with over 100 deaths from gunfights. Despite harsh desert conditions and lawlessness across its 25 saloons, Benton’s violent legacy tells a fascinating tale of the American West’s untamed spirit.

Key Takeaways

- Benton existed for only three months in 1868 as a Union Pacific Railroad town before becoming abandoned by December that year.

- The town rapidly grew to 3,000 residents and featured 25 saloons and 5 dance halls during its brief existence.

- Located 11 miles east of present-day Rawlins, Benton was known as Wyoming Territory’s deadliest frontier settlement with over 100 violent deaths.

- Harsh desert conditions, alkaline soil, and scarce water made living conditions extremely difficult for residents.

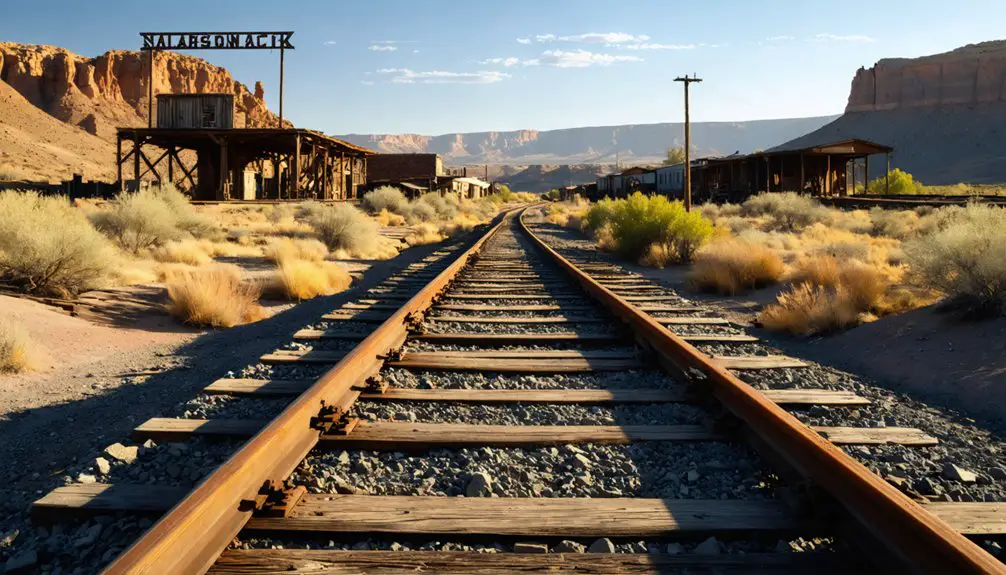

- Today, Benton stands as a ghost town, representing the temporary “Hell on Wheels” settlements that followed railroad construction westward.

The Birth of Wyoming’s First Ghost Town

When the Union Pacific Railroad pushed westward across Wyoming Territory in 1868, it gave birth to Benton – a quintessential “Hell on Wheels” town that would become the region’s first ghost town.

You’ll find Benton’s origins tied directly to the railroad expansion, springing up as a temporary settlement about 11 miles east of present-day Rawlins. Named after Senator Thomas Hart Benton, this makeshift community quickly swelled to 3,000 souls, mostly railroad workers living in tents and rough-built shanties near the North Platte River.

During its brief three-month existence from July to September 1898, an astounding over 100 men died in gunfights on Benton’s lawless streets. As the western terminus of the Union Pacific line, it served as a vital jumping-off point for both railroad construction crews and Mormon settlers heading to Utah. Despite its bustling atmosphere with twenty-five saloons and dancehalls, the town emerged as a perfect example of the wild frontier settlements that followed the tracks westward during America’s great railroad expansion.

Life in the Desert: Environmental Challenges

Despite its brief existence as a bustling railroad town, Benton’s harsh desert environment posed relentless challenges to its inhabitants.

You’d have faced extreme temperature swings, from scorching summers to freezing winters, while battling persistent windstorms that swept across the open terrain. Living at 9,925 feet elevation made weather conditions especially severe and unpredictable. Desert survival meant adapting to the alkaline soil’s limitations, where farming was nearly impossible and vegetation remained sparse.

Environmental adaptation became essential as you’d struggle with limited water sources. The North Platte River provided some relief, but its seasonal flow and the surrounding alkaline flats made accessing fresh water difficult. Whiskey outpriced water in this harsh frontier environment.

You’d have to rely heavily on imported supplies, as the poor soil conditions couldn’t sustain local agriculture. The isolation, intensified by winter snowstorms in nearby elevations, made getting those critical supplies even more challenging.

The Dark Side of the Boom Town

You’ll find Benton’s three-month legacy was stained with over 100 deaths from gunfights, as the town’s 25 saloons and 5 dance halls fueled widespread violence and mayhem.

The atmosphere in this railroad boomtown became so depraved that observers compared it to the biblical cities of Sodom and Gomorrah.

Murder was a daily occurrence in this settlement of 3,000 people, where law and order took a back seat to the brutal realities of frontier life.

The streets were nearly impassable with eight inches of dust, making travel difficult and leaving newcomers looking disheveled.

Even President Ulysses S. Grant witnessed the town’s notorious reputation during his visit in 1868, showcasing just how significant this brief but violent chapter of Western history had become.

Violence and Lawlessness Reign

The blood-soaked streets of Benton epitomized the darkest elements of America’s western railroad boom towns. In just three months, law enforcement failures led to over 100 deaths from gunfights, while a relentless crime wave swept through the Wyoming Territory settlement.

You’d witness chaos at every turn as the town’s 3,000 residents navigated a landscape of:

- Twenty-five saloons and five dance halls where gambling, drinking, and prostitution flourished unchecked.

- Armed outlaws operating freely, transforming streets into deadly shooting galleries.

- Daily violence fueled by a volatile mix of railroad workers, criminals, and fortune seekers.

With minimal government presence and ineffective lawmen, Benton’s descent into lawlessness proved unstoppable. By December 1868, the town had completely vanished as severe water shortages drove away the remaining residents.

The town’s reputation as a “modern Sodom” reflected the complete breakdown of civilized society, ultimately leading to its rapid abandonment.

Deadly Three Month Legacy

While lawlessness defined Benton’s character, its three-month legacy painted an even darker portrait of frontier life.

You’d be hard-pressed to find a deadlier boomtown in the American West, with over 100 men falling in gunfights during its brief existence. As transient workers flooded in, the population swelled to 3,000, mostly living in crowded tents amid desperate conditions. Committees of Vigilance attempted to maintain some semblance of order in the chaotic environment.

Death became so commonplace that they built a cemetery on day one. With water costing a dollar per barrel, basic hygiene was a luxury few could afford.

The mix of poor sanitation, rampant violence, and vice-driven economy turned Benton into Wyoming Territory’s first ghost town. Even today, it stands as a stark reminder of how quickly a frontier settlement could rise, thrive, and violently collapse.

The history of Tubb Town, Wyoming is a testament to the challenges faced by early settlers in the region. Once a bustling hub for traders and miners, it too fell victim to the harsh realities of the frontier life. Today, its remnants hint at a vibrant past, inviting explorers to uncover its lost stories.

Notable Visitors and Historical Events

Despite its brief three-month existence, Benton attracted several notable figures to its dusty streets, including Civil War hero General Ulysses S. Grant. Famous Western novelist Zane Grey also made his way through this infamous Wyoming settlement, adding to its cultural significance. Like many early Wyoming towns near South Pass City, miners flocked to the region seeking their fortunes.

From Civil War generals to frontier novelists, Benton’s brief existence drew remarkable visitors to its lawless streets.

You’ll find Benton’s most notable events centered around its reputation for lawlessness and vice:

- The town operated 25 saloons and five dance houses, drawing thousands of railroad workers.

- Daily gunfights and murders claimed over 100 lives during the summer of 1898.

- The infamous “Big Tent” gambling hall relocated from Colorado, becoming a symbol of the town’s wild nature.

Without formal law enforcement, Benton earned such a notorious reputation that observers compared it to Biblical Sodom and Gomorrah, cementing its place in Western folklore. Like many boom and bust towns of the era, Benton’s rapid decline left behind only foundations and memories of its brief but tumultuous existence.

Railroad Development and Economic Impact

Beyond its notorious reputation for lawlessness, Benton emerged as a direct product of Union Pacific Railroad‘s ambitious westward expansion.

You’ll find its origins tied directly to the railroad’s arrival at milepost 672.1 in mid-1868, where economic speculation reached a fever pitch as land prospectors rushed to capitalize on potential depot locations.

The town’s economy thrived briefly but intensely, driven by merchants catering to railroad workers and construction crews.

You’re looking at a classic example of how railroad expansion shaped Wyoming’s development, with Fort Fred Steele’s military presence adding another layer of complexity to settlement patterns.

As construction crews pushed westward, Benton’s fortunes followed the tracks, and by late 1868, the town had already begun its swift decline as residents and businesses chased the next opportunity down the line.

Daily Life in a Temporary Settlement

As residents endured life in Benton’s harsh alkali desert during the summer of 1868, you’d find a bustling but primitive settlement of 3,000 souls packed into makeshift tent shanties.

The transient lifestyle revolved around railroad work and basic survival. You’d spend your days:

- Hauling water from the North Platte River at a dollar per barrel

- Working the rails – grading, laying track, and handling freight

- Battling constant dust storms while maneuvering streets coated in alkali powder

After grueling daily routines, workers sought escape in the town’s 25 saloons and dance halls.

Exhausted railroad workers found their nightly solace among Benton’s two dozen rowdy saloons, drowning the day’s hardships in whiskey and entertainment.

With no permanent infrastructure or law enforcement, you’d witness a wild atmosphere where gambling, drinking, and gunfights dominated the nights.

The dangerous conditions and lawlessness made Benton one of the deadliest settlements in Wyoming Territory.

The Price of Lawlessness: Crime and Violence

The lawless streets of Benton earned a reputation as Wyoming Territory’s deadliest frontier settlement, where you’d find over 100 souls meeting violent ends during the town’s brief three-month existence in 1868.

Contemporary observers likened it to “a modern Sodom,” and crime statistics reveal why – armed outlaws roamed freely, robberies were commonplace, and gunfights erupted daily around the town’s 25 saloons and five dance halls.

The outlaw culture thrived without any real law enforcement, as bandits openly carried revolvers and bowie knives while conducting their criminal enterprises.

Wells Fargo stagecoaches fell prey to robbery, while gambling disputes and drunken brawls regularly turned deadly.

This unchecked violence ultimately helped seal Benton’s fate, deterring legitimate settlement and leading to its rapid abandonment.

Water Woes and Living Conditions

While Benton’s lawlessness drove many away, its harsh environmental conditions made life nearly unbearable for those who remained. You’d have faced some of the worst living conditions imaginable in this temporary hell-on-rails, where water quality was so poor that even livestock wouldn’t drink it.

Here’s what you’d have endured in Benton:

- Water so scarce it cost up to $1 per barrel, hauled in from the distant Platte River

- Constant winds whipping alkali dust through canvas tents and makeshift shanties

- Red, vermin-contaminated water that made every sip a gamble with your health

Living in one of the 3,000-person settlement’s tents or wooden shacks, you’d have battled the elements daily, surrounded by a barren desert landscape that offered no natural vegetation or drinkable water sources.

The Legacy of “Hell on Wheels”

Originating in Omaha during 1865, Hell on Wheels towns blazed a lawless trail westward alongside Union Pacific’s expanding railroad, leaving an indelible mark on American frontier history.

These transient communities, like Benton, embodied the raw spirit of westward expansion, where fortunes could be made or lost in an instant.

Wild fortunes rose and fell as Hell on Wheels towns raced westward, chasing dreams across America’s untamed frontier.

You’ll find the legacy of these mobile settlements in stories of remarkable chaos and opportunity, where gambling halls and saloons ruled the landscape.

While most Hell on Wheels towns vanished as quickly as they appeared, they shaped the development of the American West.

Even today, you can trace their impact through ghost towns like Benton, which grew to 3,000 residents before disappearing into Wyoming’s wind-swept plains, serving as a symbol of the fleeting nature of frontier boom towns.

Frequently Asked Questions

What Happened to the Buildings and Structures After Benton Was Abandoned?

You’ll find minimal building preservation since structures quickly deteriorated from harsh weather and neglect. Unlike popular ghost town tourism sites, most buildings collapsed or were salvaged, leaving only scattered foundations today.

Were There Any Children or Families Living Among the Rough Population?

You won’t find many stories of childhood experiences here – historical records show virtually no families among the 3,000 residents. The harsh conditions, violence, and temporary nature discouraged family dynamics entirely.

How Much Did Basic Goods and Services Cost in Benton?

You’d pay dearly for basic necessities, with a barrel of water costing $1 – a high historical price. The cost of living reflected harsh conditions, while entertainment and food prices soared above typical frontier rates.

Did Any Native American Tribes Interact With the Town?

You’ll find Native interactions were primarily with Shoshone and Arapaho tribes, who’d traveled through the area’s hunting grounds. Tribal history shows they likely crossed paths during trade and seasonal movements.

What Was the Average Temperature and Weather Conditions Throughout Benton’s Existence?

You’d have roasted during those scorching 75-85°F days, but climate patterns brought relief with cool 40-50°F nights. Weather extremes were typical for Wyoming’s semi-arid summer, with occasional thunderstorms breaking the heat.

References

- https://www.gatheringgardiners.com/2010/11/benton-wyoming.html

- https://www.wyomingcarboncounty.com/blog/123-5-ghost-towns-to-explore

- https://cowboystatedaily.com/2024/11/09/wyoming-history-in-1868-benton-was-so-violent-murder-was-part-of-daily-life/

- http://www.wyomingtalesandtrails.com/sherman3.html

- https://sites.rootsweb.com/~wytttp/ghosttowns.htm

- https://www.instagram.com/p/DGQVsePvE1M/?hl=en

- https://wyomingwhispers.com/battle-wy-ghost-town/

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ErvYfYCW0qk

- https://wyomingwhispers.com/benton-wy-ghost-town/

- https://www.wyohistory.org/encyclopedia/carbon-county-wyoming