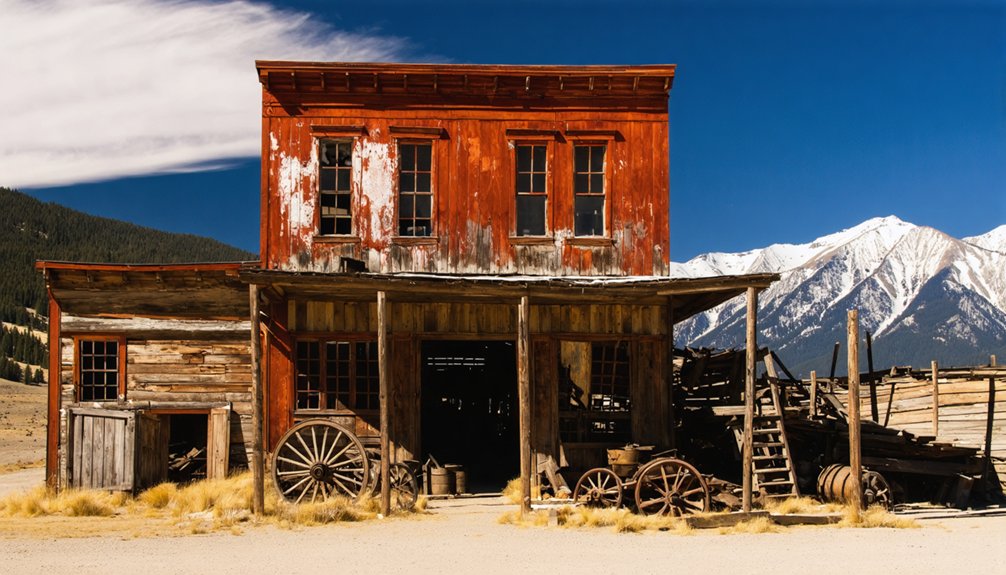

Oregon’s abandoned mining ghost towns offer haunting glimpses into frontier life. You’ll discover perfectly preserved Buncom with its three historic buildings, temperance-focused Golden with its 1892 church, Sumpter’s impressive dredge and railway, the solitary Sterlingville Cemetery, Shaniko’s transformation from wool capital to historic site, nearly-deserted Granite with decaying structures, and high-elevation Greenhorn, crippled by the 1942 mining ban. Each ghost town reveals unique stories of ambition, community, and ultimate abandonment across Oregon’s rugged terrain.

Key Takeaways

- Buncom preserves three historic structures (bunkhouse, cookhouse, post office) and celebrates its Chinese mining heritage through annual community events.

- Golden stands out as a temperance-focused mining town with preserved religious buildings, completely banning saloons and brothels.

- Sumpter features the historic Sumpter Valley Dredge and “Stump Dodger” railway, showcasing its gold mining prosperity before the 1917 fire.

- Shaniko, once the “Wool Capital of the World,” offers authentic wooden sidewalks and preserved building facades from its railroad shipping heyday.

- Greenhorn and Granite represent high-elevation mining settlements with significant gold extraction history and visible 19th-century structural remains.

Buncom: Oregon’s Best-Preserved Mining Ghost Town

While countless mining settlements have disappeared entirely from Oregon’s landscape, Buncom stands as a remarkable survivor of the state’s gold rush era. Founded in 1851 by Chinese miners following gold discoveries near Sterling Creek, this unincorporated community flourished with saloons, stores, and its own post office by 1896.

Buncom history reflects the boom-and-bust cycle common to mining towns—thriving until 1918 when gold deposits depleted. At its peak, the town served as a hub for various professions including miners and farmers who settled in the area. The town is well-preserved in part due to the community-driven preservation efforts that emphasize local history and heritage.

Like countless boomtowns before it, Buncom flourished with golden dreams until the earth yielded no more treasure.

What sets it apart is the Buncom architecture still visible today: three preserved structures including a bunkhouse, cookhouse, and post office. The Buncom Historical Society maintains these treasures through annual events like Buncom Day.

You’ll find this historical gem about 20 miles southwest of Medford, offering a rare glimpse into Oregon’s mining heritage.

Golden: The Teetotaling Gold Rush Settlement

Unlike Buncom’s typical mining town character, Golden represents a rare anomaly in Oregon’s gold rush history. Founded in 1852 along Coyote Creek, this settlement defied frontier expectations by completely banning saloons and brothels—establishing unique community values centered on temperance, family, and religious devotion.

You’ll find the 1892 Campbellite church and 1904 general store still standing as symbols of Golden’s temperance mining legacy. While other boomtowns catered to miners’ vices, Golden’s residents focused on sobriety and moral standards, creating a family-oriented hub that peaked at about 100 inhabitants. The settlement’s unique approach contrasted sharply with the typical mining economy where businesses often thrived by mining the miners rather than extracting gold themselves.

Despite extracting an estimated $20 million in gold through placer and hydraulic mining, Golden maintained its distinctive character. Reverend William Ruble and his wife Ruth established the church at the center of the community, emphasizing the town’s focus on religious life and morality.

Now preserved as a National Historic Site, this well-maintained ghost town offers a fascinating glimpse into an alternative frontier mining community.

Exploring abandoned towns in Pennsylvania can evoke a sense of nostalgia for a bygone era. Each site holds stories of resilience and hardship, showcasing the rich history of the region’s industrial past. Visitors can wander through crumbling buildings and overgrown streets, imagining the lives once lived there.

Sterlingville Cemetery: The Last Remnant of a Booming Mining Community

When you stand at Sterlingville Cemetery today, it’s difficult to imagine that a thriving boomtown of 1,200 souls once bustled around this peaceful hillock.

This well-maintained cemetery is the sole physical remnant of a community born from James Sterling’s 1854 gold strike.

Follow Sterling Creek Road south of Jacksonville to discover this hidden historical gem.

Surrounded by towering eucalyptus and fir trees, the cemetery offers more than just a destination for cemetery tours—it’s a tangible connection to Oregon’s gold mining heritage.

A prominent sign recounts how hydraulic mining operations transformed this slice of the Applegate watershed into one of Oregon’s largest mining enterprises.

The earliest marked grave in the cemetery dates back to 1863, preserved through the dedicated efforts of local historical societies.

The once-vibrant town supported numerous businesses including a bakery and warehouse, providing services to the mining population.

Sumpter: Blue Mountain Ghost Town With Historic Railroad

Nestled in the majestic Blue Mountains of eastern Oregon, Sumpter stands as a tribute to the boom-and-bust cycle of America’s mining frontier. Founded in 1862 by ex-Confederates who struck gold along Cracker Creek, this once-thriving town ballooned to over 3,000 residents after the railway arrived in 1897.

Sumpter history took a dramatic turn when a devastating 1917 fire destroyed nearly 100 buildings, accelerating its decline. The fire originated from the Capital Hotel and spread rapidly through the wooden structures. Today, with barely 120 year-round residents, it’s a semi-ghost town offering freedom-seekers a glimpse into Oregon’s golden past.

Sumpter attractions include the massive Sumpter Valley Dredge that processed nine tons of gold, and the “Stump Dodger” heritage railway offering scenic 12-mile journeys through timber country. The railway, established in the 1880s, was named for its practice of following timber lines while avoiding tree stumps along its path.

You’ll find excellent ATV trails, snowmobiling, and access to the rugged Blue Mountains wilderness.

Shaniko: From Wool Capital to Preserved Historic Site

When you visit Shaniko today, you’ll find not a mining town but the remarkably preserved remnants of what was once proudly known as the “Wool Capital of the World.”

Unlike many ghost towns that vanished completely, Shaniko’s historic buildings—including the recently reopened Shaniko Hotel and iconic water tower—stand as symbols to preservation efforts by the dedicated Shaniko Preservation Guild.

The town’s transformation from a bustling wool shipping center with 600 residents to a ghost town of just 20-30 people offers visitors a tangible connection to Oregon’s agricultural past rather than its mining heritage. In its peak year of 1903, the town shipped an impressive 2,229 tons of wool, generating profits equivalent to nearly $200 million in today’s currency. Exploring the town is best done on foot, allowing visitors to fully appreciate the historic architecture and atmosphere while capturing memorable photographs.

Historical Economic Boom

The economic transformation of Shaniko stands as one of Oregon’s most remarkable boom stories outside the mining industry.

Unlike typical gold rush towns, this “Wool Capital of the World” flourished through agricultural trade, generating a staggering $5 million annually in wool sales by 1904.

When you visit today, you’ll see remnants of a town that once hosted record-breaking wool auctions—including a single day in 1903 when sales exceeded $1 million.

The Columbia Southern Railroad transformed this outpost into Oregon’s fifth-largest inland shipping hub after Portland, complete with impressive brick warehouses and a 10,000-gallon water tower.

The wool industry’s collapse came swiftly after 1911 when the Oregon Trunk Railroad diverted traffic elsewhere.

Devastating fires, coupled with this economic decline, rapidly transformed this booming center into the preserved ghost town you can explore today.

Preservation Efforts Today

While the economic collapse of Shaniko’s wool industry transformed it into a ghost town, passionate preservation efforts have breathed new life into this historic treasure.

You’ll find the Shaniko Preservation Guild and South Wasco Fire and Rescue Association at the forefront of restoration techniques, exemplified by the recently reopened Shaniko Hotel—a National Register landmark since 1979.

Community involvement shines through annual events like the Wool Gathering, which draw visitors to experience authentic wooden sidewalks and meticulously preserved building facades.

When you visit, explore the Shaniko Sage Museum‘s collection of artifacts maintained by dedicated locals despite the town’s tiny population of just 23 residents.

The harmonious balance of tourism and preservation guarantees these structures retain their genuine historic character rather than succumbing to modernization.

Shaniko’s recognition as “Oregon’s Ghost Town of the Year” in 1959 cemented its cultural importance.

Granite: a Nearly Deserted Mining City With Declining Population

Founded on the promise of gold discovered by A.G. Tabor on Independence Day 1862, Granite embodies the boom-and-bust cycle of Oregon’s mining heritage. Initially named Independence, this settlement was renamed in 1878 for the abundant igneous rock surrounding it.

At its peak, 5,000 residents enjoyed six hotels, multiple restaurants, and all the amenities of a thriving gold town. Miners employed both placer mining techniques in riverbeds and vein mining in hillsides, extracting over $2 million in gold by 1914.

World War II’s gold mining ban devastated Granite, reducing the population to just two residents by 1960.

Today, with only 38 inhabitants, this partial ghost town features decaying 19th-century structures along its main street—a hauntingly beautiful memorial to freedom-seekers who once chased fortune in Oregon’s wilderness.

Greenhorn: The Ghost Town Created by the 1942 Mining Ban

Among Oregon’s most poignant mining legacies, Greenhorn stands as a tribute to how government policy can instantly transform a thriving community into a ghost town.

Greenhorn history began with an 1864 gold discovery, eventually growing to 3,200 residents by the 1890s. You’ll find this former mining hub perched at 6,300 feet—once Oregon’s highest incorporated city.

While decline started early, with population dwindling after 1900, the final blow came when Public Law 208 banned gold mining nationwide in 1942.

Before its demise, Greenhorn boasted hotels, stores, saloons, and a wooden jail. The town’s mining legacy includes major operations like the Bonanza Mine, which sold for $750,000 in 1898.

Though Miles Potter attempted revival in 1971, Greenhorn remains largely abandoned—a silent reflection of boom-and-bust cycles of Western mining towns.

Frequently Asked Questions

Are Any Oregon Ghost Towns Known to Be Haunted?

You’ll discover many haunted legends in Golden, Sumpter, and near The Witch’s Castle, where paranormal experiences aren’t coincidentally tied to tragic mining accidents, fires, and isolation that plagued Oregon’s forgotten towns.

What Safety Precautions Should Visitors Take When Exploring Abandoned Mines?

Never enter abandoned mine shafts! You’ll risk your life from collapsing structures, hidden shafts, toxic air, and unstable explosives. Prioritize mine safety through visitor awareness—stay outside and photograph from a distance.

Can Tourists Legally Collect Artifacts From These Ghost Towns?

No, you can’t legally collect artifacts. State and federal regulations protect these historical treasures for everyone’s benefit. Honor artifact preservation by taking photos instead—you’ll avoid hefty fines while respecting Oregon’s cultural heritage.

When Is the Best Season to Visit Oregon’s Ghost Towns?

Summer sees 75% of Oregon’s ghost town visitors. You’ll enjoy ideal weather conditions from April to September, with seasonal attractions like Shaniko Days festival enhancing your exploration of these time-frozen treasures.

Are Any of These Ghost Towns Completely Off-Grid Without Cell Service?

You’ll find truly off-grid towns like Greenhorn and remote parts of Sumpter where cell service vanishes completely. These isolated treasures offer genuine disconnection amid Oregon’s rugged wilderness terrain.

References

- https://indigocreekoutfitters.com/news/2022/05/05/exploring-southern-oregons-ghost-towns/

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=knJcpdeY2Ko

- https://www.travelmedford.org/southern-oregon-ghost-towns-

- http://pnwphotoblog.com/ghost-towns-oregon/

- https://www.visitoregon.com/oregon-ghost-towns/

- https://www.wikiwand.com/en/articles/List of abandoned communities in Oregon

- https://www.deviantart.com/austinsptd1996/journal/Six-Iconic-Ghost-Towns-Within-Oregon-1109696435

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_ghost_towns_in_Oregon

- http://www.photographoregon.com/ghost-towns.html

- https://traveloregon.com/things-to-do/culture-history/ghost-towns/