You’ll discover Delaware’s most compelling ghost towns by exploring Zwaanendael, the state’s first European settlement destroyed in 1631, and the storm-ravaged resort town of Woodland with its scenic fishing pier. Don’t miss Saint Johnstown’s abandoned railroad stop and church, or Fort Delaware on Pea Patch Island, where Confederate prisoners once resided. Sussex County holds additional forgotten communities, each telling unique tales of colonial ambition, industrial decline, and nature’s reclamation.

Key Takeaways

- Zwaanendael, near present-day Lewes, was Delaware’s first European settlement before its destruction in 1631, now marked by a memorial museum.

- Saint Johnstown, between Ellendale and Greenwood, features an abandoned railroad stop and historic church from the Queen Anne’s Railroad era.

- Glenville became a ghost town after devastating floods from Red Clay Creek, with nature reclaiming the abandoned watershed.

- Woodland transformed from a popular resort town to an abandoned settlement after destructive storms in 1878 and 1914.

- Fort Delaware on Pea Patch Island, though not entirely abandoned, features historic ruins and reportedly haunted Civil War-era structures.

The Historic Rise and Fall of Zwaanendael

While Native American tribes had long inhabited Delaware’s coastal regions, the first European settlement in the area emerged when Dutch directors Samuel Blommaert and Samuel Godyn negotiated land rights in 1629.

The Zwaanendael settlement, established in 1631 near present-day Lewes, marked the beginning of Dutch colonization in Delaware. The name of the settlement translated to the poetic Valley of the Swans.

The Zwaanendael settlement’s origins lie in the arrival of thirty-two colonists aboard the Walvis, who constructed a palisaded fort displaying Holland’s red lion at its gate. Only two boys survived the violent end of the settlement.

They’d planned to hunt whales and cultivate tobacco, but their ambitions were tragically cut short. Within a year, cultural misunderstandings led to conflict with local natives, resulting in the death of all settlers and the burning of the settlement.

When David Pietersz de Vries arrived in December 1632, he found only the charred remains of what had been Delaware’s first European outpost.

Delaware’s Earliest European Ghost Settlement

You’ll find Zwaanendael’s haunting origins in the Dutch trading post established on December 12th, 1630, when twenty-eight settlers aboard the Walvis arrived at Blommaert’s Kill to build a whaling station.

Despite constructing a palisade and dormitory, the settlement met a tragic end when cultural misunderstandings between Dutch traders and local Native Americans led to a deadly raid that killed all inhabitants.

The settlers initially established trade for beaver furs with the local Native American tribes before their demise.

Captain John Smith had previously explored and documented the Delaware region before the Dutch settlement attempt.

The site’s legacy lives on through the De Vries Monument, placed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1972, marking Delaware’s earliest European ghost settlement and foreshadowing later colonial developments in the region.

Dutch Trading Post Origins

Before Swedish settlers established their colony at Wilmington, the Dutch West India Company launched Delaware’s first European settlement at Zwaanendael in 1631.

The settlers encountered a land dominated by towering primeval trees that stretched unbroken across the wilderness.

You’ll find this historic site marked by a memorial on Pilottown Road near the Rehoboth-Lewes Canal, where directors Samuel Blommaert and Samuel Godyn originally bargained with the Siconese Indians for land stretching from Cape Henlopen to the Delaware River mouth.

The Zwaanendael settlement, meaning “Valley of the Swans,” featured a palisaded fort adorned with Holland’s red lion emblem.

Twenty-eight men constructed this trading post to capitalize on the region’s lucrative fur trade. Under merchant David Pietersz. de Vries‘s guidance, the Dutch sought to trade European goods for beaver pelts with the Lenape and other native tribes along what they called Godyn’s Bay. Tragically, the settlement only survived a few months before Siconese Indians destroyed it.

Violent End and Legacy

Despite the Dutch West India Company‘s ambitious plans for Zwaanendael, the settlement met a swift and violent end in 1631 when Native American raiders completely destroyed the outpost, leaving no survivors.

The Zwaanendael raid resulted from escalating tensions over territorial claims and fur trading rights between settlers and local tribes, including the Lenape and Minquas.

You’ll find this pivotal moment of Native American resistance marked today by the Zwaanendael Museum in Lewes, where you can explore Delaware’s earliest European ghost settlement.

The conflict began when Native Americans removed a Dutch coat insignia, leading to hostilities that ultimately sealed the settlement’s fate.

Similar to how Peter Stuyvesant defeated Swedish settlers in 1651, the site’s destruction delayed colonial expansion in southern Delaware until the Swedes established Fort Christina in 1638.

The site’s destruction delayed colonial expansion in southern Delaware until the Swedes established Fort Christina in 1638.

While the Dutch never rebuilt the settlement, Zwaanendael’s violent end stands as a reflection of the complex dynamics of early colonial-indigenous relations in the Mid-Atlantic region.

Weather’s Impact on Glenville’s Abandonment

While many ghost towns emerge from economic decline or industrial obsolescence, Glenville’s fate was sealed by its precarious position along Red Clay Creek in New Castle County.

The low-lying terrain you’ll find there made the community exceptionally vulnerable to flooding consequences, with residents facing repeated evacuations and property damage from the creek’s overflow.

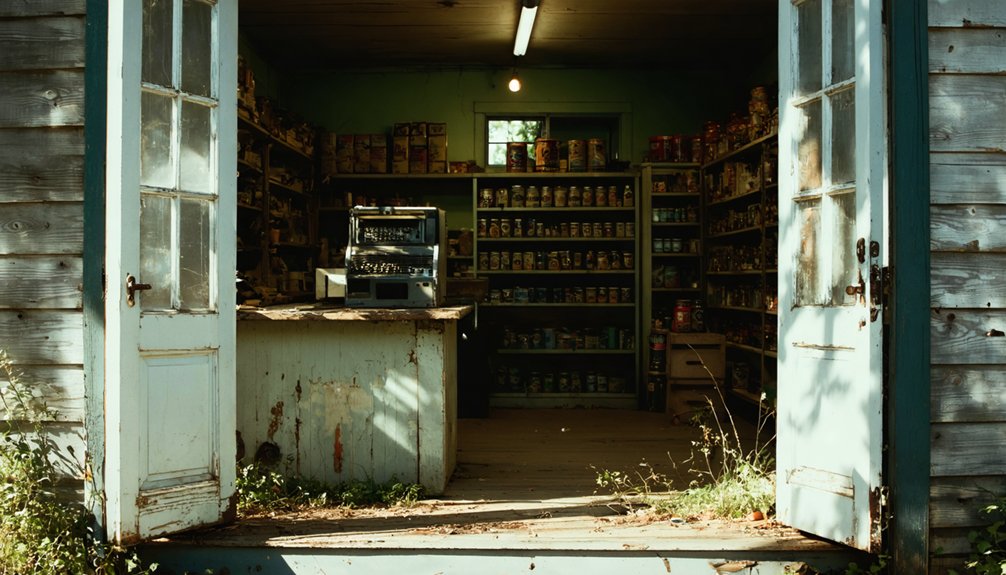

Exploring Woodland’s Lost Community

You’ll find Woodland’s tragic economic downfall rooted in the devastating storms of 1878 and 1914, which systematically destroyed its once-thriving resort infrastructure including the hotel, pavilion, and steamboat pier.

The community’s transformation from a popular coastal destination to an abandoned settlement occurred rapidly, as repeated natural disasters prevented any meaningful recovery efforts.

Today, nature has reclaimed much of what remains, leaving only traces of the former resort town where weathered ruins stand as silent witnesses to Woodland’s lost prosperity. Local visitors claim the ruins are most active during blue moon nights, when unexplained phenomena frequently occur. Visitors can now experience the area’s enduring legacy through its scenic fishing pier, which continues to attract outdoor enthusiasts.

Historical Economic Decline

Once a thriving coastal destination in the late 1800s, Woodland Beach Resort’s economic decline stemmed from two devastating storms that fundamentally altered its trajectory.

You would’ve found a vibrant scene there in the 1880s, complete with a hotel, dancing room, and daily orchestra performances led by William Oglesby. Visitors arrived by steamer, wagon, and car to enjoy the boardwalk and pavilion.

The catastrophic 1878 hurricane first devastated the area with a ten-foot tidal wave, though the community managed to rebuild.

However, the 1914 nor’easter delivered the final blow, destroying nearly every structure. This double impact transformed Woodland Beach from an entertainment destination into a quiet fishing village.

The economic transformation was complete – no more steamers, no more orchestras, just scenic sunrises and forgotten memories of its resort glory days.

Nature Reclaims Settlement

The dramatic transformation of Delaware’s ghost towns extends beyond economic decline into a fascinating story of nature’s reclamation.

You’ll discover forgotten landscapes where wilderness has steadily overtaken once-thriving communities, creating hauntingly beautiful scenes of natural rebirth.

- At Glenville, Hurricane Floyd’s devastating floods in 1999 marked the final chapter, as nature reclaimed the settlement through destructive force, transforming it into an abandoned watershed.

- The Crowninshield Garden ruins showcase nature’s artistic touch, where industrial remnants have morphed into verdant grottoes and vine-covered pools, particularly after the 2019 controlled burning cleared decades of overgrowth.

- Fort DuPont’s remaining 80 structures stand as silent sentinels, gradually surrendering to vegetation’s advance, while Gibraltar Mansion’s gardens evolved from manicured splendor to wild tangles before preservation efforts prevailed.

The Mysterious Saint Johnstown

Situated between Ellendale and Greenwood in Sussex County, Saint Johnstown stands as one of Delaware’s most enigmatic ghost towns.

You’ll find this former railroad stop‘s legacy intertwined with the defunct Queen Anne’s Railroad line, which once served as its lifeline for both passengers and freight.

The Saint Johnstown Church remains the most prominent reminder of this vanished settlement, fueling ghost town legends and capturing the imagination of history enthusiasts.

You can trace the community’s decline directly to the railroad’s abandonment, marking a familiar pattern among Delaware’s lost towns.

While no active buildings or permanent residents remain today, Saint Johnstown’s historical significance persists in local records, offering you a glimpse into an era when rail-dependent communities dotted Sussex County’s landscape.

Fort Delaware: From Military Post to Haunted Isle

Standing sentinel on Pea Patch Island in the Delaware River, Fort Delaware represents one of the state’s most compelling ghost towns, evolving from a military stronghold to an allegedly haunted historical site.

The fort’s history spans three distinct fortifications, with the current pentagonal structure dating from 1848-1860.

During the Civil War, the fort transformed into a prisoner-of-war camp, where you’ll discover:

- Over 30,000 Confederate soldiers were imprisoned here

- The notorious Ahl’s Independent Battery formed from prisoners who switched allegiance

- Countless deaths occurred, contributing to the isle’s haunted reputation

Today, you can explore the restored third system fort, where ghost sightings are frequently reported.

The original sandstone remnants, moat, and Endicott Period gun batteries stand as silent witnesses to its military past and paranormal present.

Vanishing Communities of Sussex County

Deep within Sussex County’s rural landscape, you’ll find a collection of fascinating ghost towns that paint a vivid picture of Delaware’s industrial and colonial past.

You can explore the haunting remnants of Fenwick Lighthouse, where two families once tended the oil-powered beacon, or venture to Old Furnace along Deep Creek, a representation of the region’s vanished iron industry.

The area’s most dramatic ghost town story belongs to Zwaanendael, Delaware’s first settlement, which met a tragic end in 1631 after Native Americans killed all Dutch settlers within a year of its founding.

At Robinsonville‘s three-way junction and Pine Grove Furnace‘s abandoned ironworks, you’ll discover how these once-thriving communities gradually faded as manufacturing declined and agricultural patterns shifted, leaving behind compelling remnants of Sussex County’s rich history.

Hidden Stories of Andrewsville

Along the quiet stretches of Kent County lies Andrewsville, a tiny settlement whose haunting legacy intertwines with Delaware’s vanished industrial heritage.

You’ll discover a place where Andrewsville Legends persist through generations, centered around the mysterious Andrews Lake and its dark past.

The ghostly tragedies that define this abandoned community include:

- A chilling tale of conflict at the local bark mill, where a worker’s fate became forever sealed in local folklore.

- The enigmatic story of Quaker Bonwell’s brick house by the pond, which still echoes through Kent County’s history.

- The gradual decline of resource-based industries that transformed this once-thriving settlement into a haunting reminder of Delaware’s industrial past.

Today, Andrewsville stands as a symbol of the state’s vanishing communities, its stories preserved only in historical records and whispered tales.

Preserving Delaware’s Abandoned Heritage

While Delaware’s ghost towns face the persistent threat of decay, a robust network of preservation initiatives works tirelessly to safeguard these irreplaceable historical treasures.

Across Delaware’s abandoned landscapes, dedicated preservationists fight time itself to protect the state’s vanishing historical legacy.

You’ll find multiple funding sources dedicated to historic preservation, including grants from the Delaware Preservation Fund that support restoration of abandoned properties across all three counties. The State Historic Preservation Office’s tax credit program makes it financially viable for you to rehabilitate historic structures, while Preservation Delaware actively promotes the adaptive reuse of neglected buildings.

If you’re exploring these forgotten places, you’ll benefit from DelDOT’s careful archaeological oversight and local preservation ordinances that protect historic sites.

Through collaborative efforts between state agencies, nonprofits, and community groups, you can witness Delaware’s commitment to preserving its abandoned heritage for future generations.

Frequently Asked Questions

Are There Organized Ghost Tours Available at These Abandoned Delaware Settlements?

Like footprints in shifting sand, you won’t find organized ghost tour options at these sites today. While they’re rich in haunted history, these Delaware ghost towns lack formal touring operations.

What Artifacts Can Visitors Legally Collect From Delaware’s Ghost Towns?

You can’t legally collect artifacts from Delaware’s ghost towns due to strict preservation laws. Only modern trash can be removed – all historic items are protected under state and federal legal restrictions.

Which Ghost Towns in Delaware Are Accessible by Public Transportation?

Ironically, you can’t reach any of Delaware’s ghost towns directly by public transport. You’ll need to take DART buses to nearby hubs like Newcastle or Georgetown, then arrange additional transportation to these abandoned sites.

Do Any Delaware Ghost Towns Still Have Seasonal Residents?

You won’t find seasonal residents in Delaware’s ghost towns today. Based on historical records, these abandoned sites, including Glenville, Fort Delaware, and Fenwick, are solely maintained for preservation and tourism.

What Safety Precautions Should Visitors Take When Exploring These Sites?

Bring safety gear including sturdy boots, flashlights, and first aid kits. Maintain wildlife awareness, watch for unstable structures, and don’t explore alone. Always check weather forecasts and obtain proper permissions.

References

- http://freepages.rootsweb.com/~gtusa/history/usa/de.htm

- https://kids.kiddle.co/List_of_ghost_towns_in_Delaware

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_ghost_towns_in_Delaware

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ex8Hld_imPU

- https://www.geotab.com/ghost-towns/

- https://www.farmweddingde.com/wedding-blog/haunted-history-in-delaware-city-tourism-in-the-first-state

- https://www.visitkeweenaw.com/listing/delaware-the-ghost-town/515/

- https://history.delaware.gov/zwaanendael-museum/zm_history/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Zwaanendael_Colony

- https://www.atlasofmutualheritage.nl/page/10679/swanendael-fort