You’ll find fascinating ghost towns scattered across Oklahoma, each telling unique stories of dramatic rises and falls. Picher’s toxic mining legacy, Earlsboro’s whiskey-to-oil transformation, and Beer City’s lawless past offer glimpses into the state’s wild territorial days. Visit Three Sands to explore abandoned oil boomtown ruins, or head to Ingalls to walk where famous outlaws once roamed. These empty streets hold countless untold tales of Oklahoma’s adventurous frontier spirit.

Key Takeaways

ႏrakouй breakthroughส

The Toxic Legacy of Picher: A Mining Town’s Dramatic End

When lead and zinc ore was discovered on Harry Crawfish’s land in 1913, it sparked the meteoric rise of Picher, Oklahoma, a boomtown that would become one of America’s most significant mining districts.

You’ll find its mining legacy etched into history, as the town supplied over 50% of lead and zinc used in World War I and shattered Germany’s zinc monopoly in Belgium.

But Picher’s prosperity came at a devastating cost. By the time mining ceased in 1967, the town’s toxic environment included 14,000 abandoned mineshafts and 178 million tons of contaminated mining waste. To avoid confusion with other locations, historical records now specifically refer to this as Picher, Oklahoma.

The EPA designated it a Superfund site in 1983, as poisoned groundwater and unstable ground threatened residents’ lives. A devastating EF4 tornado struck in 2008, destroying over 20 blocks and sealing the town’s fate. In 2006, the government declared Picher uninhabitable, forcing everyone to relocate from this once-thriving community.

Earlsboro’s Rise, Fall, and Haunted History

You’ll find Earlsboro’s history uniquely shaped by its strategic location near Indian Territory, where prohibition laws made it a thriving whiskey town before Oklahoma statehood in 1907.

During its peak, nearly 90 percent of merchants relied on liquor sales to sustain their businesses.

The town’s resilience showed when it bounced back from the whiskey bust with a massive oil boom in 1926, though this prosperity proved short-lived as the town fell into debt and decline by 1932.

What began as a small settlement of 100 residents in its first year would experience dramatic population swings throughout its turbulent history.

Today, abandoned structures and local ghost stories, including tales of Pretty Boy Floyd’s bank robbery and the violent whiskey era, continue to draw paranormal enthusiasts to this shell of a twice-booming community.

Prohibition’s Impact and Recovery

The seemingly overnight implementation of statewide prohibition in 1907 transformed Earlsboro from a thriving whiskey town into a struggling agricultural settlement.

With liquor sales banned, the population plummeted from 500 to 387 as merchants fled to other states. Despite strict laws, bootlegging remained rampant throughout the region, mirroring the situation in Indian Territory before statehood. You’ll find that prohibition effects rippled through every aspect of the local economy, forcing the community to pivot toward farming-related enterprises like cotton gins and grain mills. The town had grown rapidly from 100 initial residents when it was founded in 1891.

But Earlsboro’s economic recovery arrived dramatically in 1926 when oil was struck at 3,557 feet.

Within two months, the population exploded to 10,000. Property values skyrocketed, with small lots fetching up to $10,000. The boom brought unprecedented development – a luxury hotel, a grand theater, dozens of businesses, and makeshift housing wherever space allowed.

Paranormal Legacy Lives On

Today’s quiet streets of Earlsboro mask its turbulent past, with just over 600 residents occupying what was once a booming metropolis of 10,000.

You’ll find abandoned homes and businesses from the 1929 era that fuel local ghostly sightings and haunted tales, remnants of the town’s dramatic rise and fall.

Among the most infamous spirits said to linger here is Charles “Pretty Boy” Floyd, who once robbed the local bank and worked as an oil field roustabout.

The $100,000 luxury hotel, once Oklahoma’s finest, may be demolished, but its memory persists in oral histories passed down through generations.

What you’re witnessing isn’t your typical ghost town – it’s a living museum where whiskey-fueled fortunes and oil dreams crumbled, leaving behind an eerie indication to boom-and-bust economics.

The town’s decline was hastened when saltwater and debris contaminated the local water supply, forcing many residents to seek cleaner water sources elsewhere.

Beer City: The Lawless Town of No Man’s Land

You’ll find Beer City’s notorious past rooted in Oklahoma’s No Man’s Land, where the absence of jurisdiction from 1850 to 1890 created a haven for those seeking to escape legal constraints.

The town emerged in 1888 as a liquor-trading outpost, complete with saloons and dance halls catering to cowboys and cattle dealers traveling between Texas Panhandle towns and Dodge City, Kansas.

While vigilante justice maintained a semblance of order through local committees, the town’s lawless reputation was cemented by events like Marshal Amos Bush’s murder in 1888, when townspeople collectively riddled his body with bullets after a dispute with Pussy Cat Nell over taxes.

Known originally as White City, the settlement earned its new name from the numerous drinking establishments that made it a bustling destination during cattle-shipping season.

The area’s outlaw reputation was further enhanced by Captain William Coe who operated a fortified hideout called Robbers Roost, conducting raids across multiple states.

Wild West Outlaw Haven

During the late 1800s, a notorious settlement known as Beer City emerged in No Man’s Land, earning its reputation as the “Sodom and Gomorrah of the Plains.”

Located in what would become Beaver County, Oklahoma, this lawless outpost drew cowboys and outlaws from nearby Kansas towns like Liberal and Dodge City.

In this haven of lawless culture, you’d find saloons like the Elephant and Yellow Snake advertising “no law in civilized world.” Many settlers survived by collecting buffalo bones for income, shipping them to nearby markets.

The town’s most notorious figures included Pussy Cat Nell, who ran the Yellowsnake Hotel, and self-proclaimed marshal Brushy Bush, who extorted local businesses.

When law and order failed, vigilante justice prevailed – committees burned offending saloons, hanged horse thieves, and banished claim jumpers.

Pre-Statehood Liquor Trade

While Oklahoma Territory’s legal status remained uncertain, Beer City flourished as a prime destination for unrestricted liquor sales in No Man’s Land.

You’d find a booming trade centered around multiple illegal taverns that catered to thirsty cattlemen, settlers, and outlaws passing through the region. The town’s strategic location near Beaver Creek crossing made it easily accessible during cattle drives, while its position in ungoverned territory meant zero restrictions on alcohol sales.

The settlement operated as a lucrative road ranch system, combining store-saloons with campgrounds where travelers could rest and drink freely.

Without courts or law enforcement to regulate commerce, Beer City’s economy thrived on its reputation as a haven for those seeking to escape the mounting pressures of prohibition elsewhere.

Three Sands: From Oil Boom to Bust

Three pivotal events shaped the rise and fall of Three Sands, Oklahoma – its 1921 oil discovery, its brief but intense boom period, and its swift decline by 1926.

Following Ernest W. Marland’s vision and geologist E. Park Geyer’s expertise, the oil discovery in Noble County’s Glenrose township sparked immediate town formation.

The pioneering vision of Marland and Geyer’s geological expertise transformed Noble County’s untamed lands into an overnight boomtown.

You’ll find the remnants of this once-bustling community along the Kay-Noble boundary, where multiple business districts and oil camps flourished during the peak years.

Key timeline markers that led to Three Sands’ ghost town status:

- June 30, 1921: Initial oil discovery with a 3,000-barrel flowing offset well

- June 15, 1923: Post office relocation from Four Corners to Three Sands

- 1926: Oil bust triggering mass exodus, followed by school closures in 1946 and complete business shutdown by 1951

Ingalls: Where Outlaws and Lawmen Clashed

You’ll step back in time at Ingalls, where the infamous 1893 shootout between U.S. Marshals and the Doolin-Dalton Gang left three lawmen dead and marked the beginning of the gang’s downfall.

The town’s strategic location near Indian Territory made it a perfect hideout for outlaws during Oklahoma’s territorial period, with gang members becoming regular fixtures in local establishments like the Ransom Saloon.

Today, you can explore the remaining historic structures and view a stone monument dedicated to the fallen marshals, with street names like Doolin and Dalton serving as permanent reminders of the town’s wild frontier past.

Famous 1893 Gang Shootout

The infamous Ingalls shootout of September 1, 1893, stands as one of Oklahoma Territory‘s deadliest confrontations between lawmen and outlaws.

Inside the Ransom Saloon, members of the Doolin-Dalton gang were drinking and gambling when a determined posse of U.S. Deputy Marshals launched their raid. The gang’s tactics and lawman bravery collided in a fierce exchange that left both sides with heavy losses.

The battle’s key moments:

- Arkansas Tom Jones fired from the O.K. Hotel’s second story, mortally wounding Deputy Hueston.

- Bill Doolin shot Deputy Marshal Speed, while Dalton wounded Deputy Shadley.

- The outlaws escaped southeast, leaving behind Jones, who surrendered after threats of dynamite.

The deadly clash claimed nine casualties, including three deputies and an innocent bystander, forever marking Ingalls’ place in frontier history.

Town’s Territorial Law Legacy

During its brief heyday as a territorial outpost, Ingalls emerged as a notorious haven for outlaws, particularly the Doolin-Dalton Gang who found refuge among sympathetic locals between their criminal pursuits.

You’ll find that territorial justice was deeply complicated here – while U.S. Marshal E.D. Nix led law enforcement efforts to maintain order, many townspeople actively supported the outlaws with food, shelter, and intelligence about marshal movements.

The town’s pivotal moment in frontier law enforcement came on September 1, 1893, when federal deputies staged a raid on the Ransom Saloon.

The ensuing gunfight claimed three marshals’ lives, marking a violent clash between territorial authority and outlaw resistance that would forever define Ingalls’s place in Oklahoma’s Old West history.

Preserved Historic Buildings Today

Today’s visitors to Ingalls can explore a collection of carefully constructed replica buildings that honor the town’s dramatic frontier past.

The historic preservation effort showcases authentic frontier replica architecture, with weathered structures carefully positioned to match the original town layout.

At the heart of Ingalls, you’ll discover:

- The imposing Pierce O.K. Hotel (Replica Ingalls Hotel), where Arkansas Tom fired upon lawmen in 1893

- The restored Wilson General Store and community schoolhouse, which now hosts weekend concerts

- The R.M. Saloon replica, marking where the infamous Doolin-Dalton Gang made their last stand

A 1938 stone monument to fallen U.S. Marshals stands as evidence to the town’s pivotal role in territorial law enforcement, while a wooden map guides you through these carefully preserved historical sites.

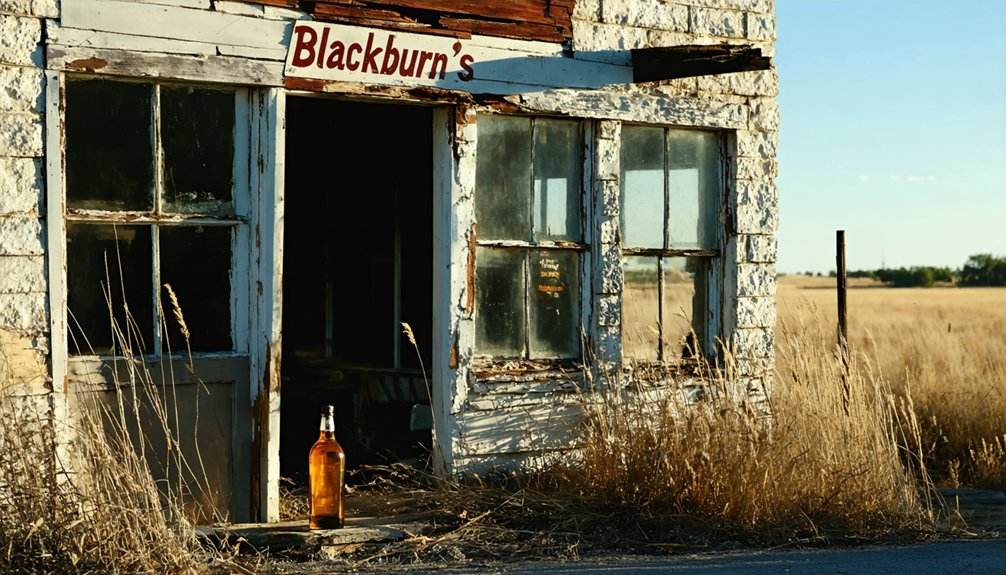

Blackburn’s Whiskey Town Legacy

Nestled along the Arkansas River’s south bank, Blackburn emerged as a notorious “whiskey town” following the Cherokee Outlet opening in 1893.

You’ll find its strategic location bordering the “dry” Osage Nation made it a perfect hub for the whiskey trade, as Oklahoma Territory allowed liquor sales while Indian Territory remained alcohol-free.

During its heyday, you could witness a bustling community profiting from alcohol sales, supported by two banks, multiple churches, and various businesses.

However, Blackburn’s fortunes changed dramatically with Oklahoma statehood in 1907 and the onset of prohibition.

The whiskey trade’s demise, coupled with severe droughts and lack of railroad access, triggered an economic decline that transformed this once-thriving border town into a quiet bedroom community of just over 100 residents today.

The Lost Communities of Lumber Mill Country

Southeastern Oklahoma’s timber industry spawned numerous lumber mill communities in the early 1900s, transforming raw wilderness into bustling towns like America, Hochatown, and Pine Valley.

During the lumber boom, these settlements offered more than just employment – they created complete communities with housing, stores, and essential services.

- America flourished with 40 buildings and 200 residents until timber depletion forced a shift to cotton production.

- Hochatown evolved from a Choctaw settlement to a thriving lumber camp before being submerged beneath Broken Bow Lake.

- Pine Valley, established by the Dierks brothers, grew into one of the South’s largest lumber towns before its ultimate abandonment.

The community decline was inevitable as forests vanished.

Today, these ghost towns stand as evidence to Oklahoma’s timber heritage, with only Stringtown surviving through industry diversification.

Bathsheba: The Mystery of the All-Female Colony

Among Oklahoma’s most enigmatic ghost towns, Bathsheba emerged in 1893 as an all-female colony halfway between Perry and Enid following the Cherokee Strip Land Run. A Kansas reporter discovered this women’s utopia, where 33 to 36 female homesteaders had established a sanctuary free from male presence.

The Bathsheba colony enforced strict rules barring all males – even animals like roosters, stallions, and boars were forbidden from the premises.

Kentucky Daisy, known for leading women settlers in the 1889 Land Run, appears in stories about the colony’s founding, though her exact role remains unclear.

While the settlement’s existence is debated, with no physical traces remaining today, its legend lives on at the Cherokee Strip Museum as a bold experiment in creating an independent female society.

Boggy Depot: From Tribal Capital to Empty Streets

While Bathsheba’s existence remains shrouded in mystery, the story of Boggy Depot stands firmly in Oklahoma’s historical record.

You’ll discover a once-thriving hub of Native American governance and commerce that showcased Boggy Depot’s significance in shaping territorial development.

As you explore this ghost town’s legacy, you’ll find three key elements that defined its prominence:

- Strategic positioning at the intersection of historical trade routes between Fort Smith and Texas

- Dual role as capital for both Choctaw and Chickasaw nations, complete with a post office established in 1849

- Religious center established by Reverend Cyrus Kingsbury that doubled as a temporary governmental seat

Despite its early promise, you’ll see how shifting immigration patterns and emerging rival towns ultimately transformed this territorial powerhouse into the abandoned site you can visit today.

Spring Lake: Where the Carnival Never Returned

In the sweltering summer of 1922, Roy Staton transformed a humble spring-fed pond in Oklahoma City into what would become Spring Lake Park, a premier entertainment destination at NE 40th and Eastern Avenue.

You’ll find the park’s history marked by stark contrasts – from its dazzling attractions to its darker chapters of racial segregation.

Spring Lake’s attractions evolved from a simple swimming pool in 1924 to the thrilling Big Dipper roller coaster in 1929. You could’ve caught performances by legends like Johnny Cash and The Beach Boys during the park’s golden era.

From swimming hole to star-studded spectacle, Spring Lake Park bloomed into Oklahoma City’s premier destination for thrills and entertainment.

But while white families enjoyed these amenities, black residents faced complete exclusion until the mid-1950s.

The park’s decline began after a 1971 racial riot, followed by fires and deteriorating conditions.

Today, only the amphitheater remains, with buried treasures beneath Metro Technology Center’s grounds.

Frequently Asked Questions

Are There Any Guided Tours Available for Oklahoma’s Ghost Towns?

You’ll find limited guided explorations, with only Fort Reno offering structured tours. Most ghost towns are accessible through self-guided Pocketsights tours that highlight their historical significance across multiple counties.

Which Oklahoma Ghost Towns Are Legal to Visit and Explore?

Want to explore Oklahoma’s forgotten places? You can legally access and explore Kenton, Texola, Shamrock, and Knowles – they’re all open for public visits through accessible roads and preserved structures.

What Is the Best Season to Explore Oklahoma’s Abandoned Towns?

You’ll find fall’s your best time for ghost town exploration, with comfortable 50-70°F temperatures, clear visibility through dying vegetation, and stable road conditions for seasonal activities like photography.

Do Any Oklahoma Ghost Towns Still Have Active Residents?

You’ll find active residents in several Oklahoma ghost towns, including Lotsee with 4 people, Lambert with 6, and Knowles with 5, maintaining small but resilient active communities and resident stories.

How Dangerous Are the Structures in These Abandoned Towns?

Crumbling walls and rusted beams stretch toward grey skies. You’ll face severe structural hazards in these buildings – they’re extremely unsafe. Take safety precautions seriously, as cave-ins and collapses can happen without warning.

References

- http://sites.rootsweb.com/~oktttp/ghost_towns/ghost_towns.htm

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5d-wHDTIbb0

- https://echo.snu.edu/the-ghost-towns-of-oklahoma/

- https://pocketsights.com/tours/tour/Shamrock-Oklahoma-Ghost-Towns-Creek-Lincoln-Payne-and-Pawnee-Counties-2749

- https://abandonedok.com/class/disappearing-town/

- https://www.okhistory.org/publications/enc/entry?entry=GH002

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Picher

- https://adamthompsonphoto.com/the-sad-tale-of-picher-oklahoma/

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pPB4Bal_mm8

- https://allthatsinteresting.com/picher-oklahoma