You’ll discover West Virginia’s most compelling ghost towns in the New River Gorge region, where abandoned settlements like Thurmond, Nuttallburg, and Kaymoor showcase America’s industrial heritage. Thurmond, once nicknamed “Dodge City of the East,” handled more freight than Richmond and Cincinnati combined, while Nuttallburg features Henry Ford’s modernized coal operations. Each site offers unique historical significance, from Kaymoor’s 821-step mining stairway to Sewell’s 200 beehive coke ovens, preserving untold stories of America’s industrial past.

Key Takeaways

- Thurmond, a former bustling railroad hub, offers a well-preserved historic district with a visitor center managed by the National Park Service.

- Nuttallburg features intact coke ovens and modernized coal production systems from its days under Henry Ford’s ownership in 1919.

- Kaymoor presents extensive mining history with an 821-step stairway, having produced over 16 million tons of coal during operations.

- Sewell showcases nearly 200 beehive coke ovens, demonstrating the massive scale of West Virginia’s historic coal production industry.

- Volcano, America’s first oil field with an endless cable pumping system, reached 4,000 residents at its peak before decline.

Historic Thurmond: A Railroad Town Frozen in Time

In the 1880s, Captain W. D. Thurmond established what would become one of West Virginia’s most significant railroad towns after receiving a 73-acre plot as payment for his surveying work.

The town earned the nickname “Dodge City of the East” due to its reputation for lawlessness and frequent violent crimes. Outside the town limits, the Ballyhack neighborhood became notorious for its saloons and brothels.

You’ll discover a town history marked by explosive growth, as Thurmond transformed from a single house in 1884 into a bustling hub where the Chesapeake & Ohio Railroad‘s freight operations surpassed those of Richmond and Cincinnati combined.

The railroad significance of Thurmond can’t be overstated. With 15 daily passenger trains, 150 railway workers, and 95,000 annual passengers by the early 1900s, you’re looking at what was once the C&O Railway’s largest revenue stop.

The town’s prosperity peaked with 462 residents in 1930, boasting the state’s wealthiest banks and a vibrant social scene that included the world’s longest poker game.

Exploring the Mining Legacy of Kaymoor

You’ll need to prepare for an intense workout as you descend the 821 steps leading to Kaymoor’s mining remnants, where the once-bustling operation produced over 16 million tons of coal from 1899 to 1962.

As you make your way down, you’re tracing the same steep path that 1,500 miners once traveled between Kaymoor Top and Bottom, where they operated 101 coke ovens and a massive processing plant.

Today, visitors can spot sections of the old rail switching yard that once connected various parts of this expansive mining complex.

The historic site’s physical remains, including the lamphouse and mine office, offer tangible connections to one of New River Gorge’s most productive mining operations, which extracted enough coal to build 18 Empire State Buildings.

The site was named after James Kay, who oversaw the construction of this remarkable mining town that would operate for over six decades.

Steep 821-Step Historic Trek

An imposing 821-step stairway, constructed by the National Park Service, now traces the historic path of Kaymoor’s original mining incline through the New River Gorge.

As you begin this ghost town exploration, you’ll descend 1,000 feet along the same route miners once traveled by cable car to reach the mine entrance. This historic mining site showcases remnants of the headhouse, mine portals, and processing facilities that operated continuously from 1899 to 1962. The miners relied on Harrison air machines for coal extraction until more modern equipment emerged in the 1930s.

You’ll find interpretive signs detailing how miners would collect their explosives and head lamps before entering the main adit. The steps preserve access to structures that processed over 16 million tons of coal during Kaymoor’s operational years. The site’s 101 coke ovens operated until 1935, converting coal into high-grade fuel for iron production.

While challenging, this steep trek offers an authentic glimpse into the daily commute of 1,500 workers who once populated this now-silent industrial complex.

Coal Production’s Physical Remnants

Three major industrial zones at Kaymoor showcase the site’s coal production legacy: the mine entrance level, the processing plant area, and the coke ovens along the New River.

You’ll discover remnants of the headhouse where loaded coal cars emerged, and the powder house where miners stored their explosives. The mining architecture reflects Kaymoor’s impressive scale, with a sophisticated double-track incline system that transported coal down the 1,000-foot slope to the processing facilities below.

At river level, you can explore the foundations of 101 coke ovens that processed one million tons of coke between 1899 and 1935. These industrial ruins stand as evidence to Kaymoor’s history as a powerhouse operation that produced nearly 17 million tons of coal during its 62-year run. Today, the site remains preserved as part of the New River Gorge National Park and Preserve.

Nuttallburg’s Industrial Heritage and Henry Ford Connection

You’ll find that Nuttallburg’s most transformative period began in 1919 when Henry Ford acquired the mines as part of his ambitious vertical integration strategy for his automobile empire.

Ford’s modernization efforts included installing a 1,385-foot conveyor belt system and constructing the innovative Henry Ford Tipple, which doubled coal production capabilities through mechanization. The facility efficiently produced 45,000 tons annually with a significantly reduced workforce. The mine produced highly desirable smokeless coal, prized for its high carbon content.

Though Ford’s ownership lasted only eight years due to transportation control issues with the C&O Railroad, his industrial improvements left an indelible mark on the site’s infrastructure, which still stands as one of America’s most complete coal mining complexes.

Ford’s Mining Operations Impact

During the early 1920s, Henry Ford’s acquisition of Nuttallburg marked a transformative period in the mine’s history, as his vertical integration strategy aimed to secure coal supplies for his River Rouge steel plant in Michigan.

Ford’s impact on the mining operations was revolutionary – you’ll find evidence of his modernization efforts in the world’s largest incline tipple he constructed in 1923-1924, making it the third such structure at the site.

His innovative 1,385-foot rope-and-button conveyor system, one of the longest globally, markedly reduced coal fragmentation during transport. These mechanical upgrades doubled coal production efficiency, while new steel structures modernized the facility.

The success of Ford’s mining modernization became evident when production peaked at over 171,000 tons annually under subsequent ownership, a proof of his industrial vision. The operation was eventually sold to New River Coal Corporation in 1928, possibly due to challenges with coal transportation regulations.

Historic Coke Oven Legacy

The legacy of Nuttallburg’s coke ovens stands as a tribute to the early industrial might of West Virginia’s coal country.

You’ll find the remnants of 80 beehive ovens that once converted coal into high-carbon coke for America’s growing steel industry. The industrial heritage of this site showcases innovative engineering, with coal transported via wooden conveyor from the mountaintop mine to the ovens below.

- Coke production earned a reputation for exceptional quality and low smoke emissions

- The ovens supplied essential materials to steel manufacturers across the eastern United States

- You can still explore the most intact coal-mining complex in West Virginia

- The site earned National Register of Historic Places recognition in 2007

These preserved coke ovens tell a compelling story of technological advancement and industrial perseverance in the New River Gorge.

Winona: Where Past Meets Present

Nestled along Keeney’s Creek in the New River Gorge region, Winona emerged in 1874 as “Devil’s Colony” before adopting its current name from Winona Gwinn, daughter of a local hotel operator.

You’ll discover a rich Winona history shaped by coal pioneer John Nuttall, who acquired 30,000 acres of coal lands and transformed the area into a thriving settlement by the 1880s.

The town’s African American heritage stands out through Carter G. Woodson‘s presence – the future founder of Black History Month taught at Winona’s school after working in nearby Nuttallburg’s coal mines.

While the population has dwindled from its 1894 peak of 200 residents, you can still explore the historic Keeney’s Creek Baptist Church and old pool hall, remnants of this once-bustling mining community.

The Coal Mining Remnants of Sewell

Originally established as Bowyer’s Ferry in the 1790s, Sewell evolved from a modest river crossing on the Charleston-Lewisburg road into a pivotal coal mining hub following the arrival of the C&O Railroad in 1873.

The town’s coke production history spans nearly a century, with its first beehive ovens constructed in 1874.

You’ll discover remarkable remnants of this industrial past:

- Nearly 200 beehive coke ovens operated at peak production, processing coal from the Sewell seam

- Underground mines reached depths of 400-500 feet, with surface operations at 2,800 feet

- Stone foundations and a preserved brick chimney stand as evidence to the mining office

- Equipment ruins, including conveyors and larry cars, scatter the landscape

The last coke ovens ceased operation in 1956, and by 1973, Sewell’s final resident departed, leaving the forest to reclaim this once-bustling industrial center.

Volcano: Wood County’s Lost Boomtown

Among West Virginia’s most spectacular boom-and-bust stories, Volcano emerged in the 1860s when William Cooper Stiles Jr. established the Volcano Oil and Coal Company on 2,000 acres in Wood County.

The town’s history skyrocketed as it became the first U.S. oil field to employ the endless cable pumping system, while also boasting the state’s first pipeline. At its peak, you’d have found nearly 4,000 residents enjoying two newspapers, an opera hall, and numerous businesses.

Tragically, a devastating fire in 1879 sealed the boomtown’s fate. The blaze, starting at 4:00 a.m., spread to oil storage tanks, creating an unstoppable inferno.

In the early morning darkness, flames devoured Volcano, transforming oil tanks into a hellish firestorm that consumed the town’s future.

Though some commercial activity resumed, Volcano’s legacy faded by the 1950s. Today, you can explore the ruins at Mountwood State Park and experience the annual “Volcano Days” celebration.

Ghost Towns Along the New River Gorge

Along the New River Gorge, you’ll find several remarkable ghost towns that showcase West Virginia’s rich coal mining heritage, including the once-bustling railroad hub of Thurmond, which processed more coal than Cincinnati in the 1920s.

You can explore well-preserved ruins at Nuttallburg, where John Nuttall’s innovative mining operation features intact coke ovens and a towering conveyor system, or venture to Kaymoor’s multi-level complex with its 560-foot elevation change between the mine portal and processing plant.

These abandoned communities, now largely protected by the National Park Service, offer tangible connections to the era when coal and railroads transformed the New River Gorge into an industrial powerhouse.

Historic Mining Communities Remain

Deep within West Virginia’s New River Gorge, numerous abandoned mining communities stand as symbols to the region’s rich industrial heritage.

You’ll discover the Kaymoor heritage through 821 stairs descending to abandoned mine entrances, where over 16 million tons of coal were extracted between 1900 and 1962.

The Nuttallburg history comes alive as one of America’s most complete coal mining sites, now preserved by the National Park Service.

- Explore Prince’s historic commerce center, once a bustling hub for surrounding mining towns

- Witness Quinnimont’s remnants, named for five surrounding mountains and former home to 500 residents

- Discover Caperton’s hulking tipples and sealed mine portals from its 1880s heyday

- Navigate Kaymoor’s extensive network of hiking trails leading to preserved processing plants and coke ovens

Railroad Town of Thurmond

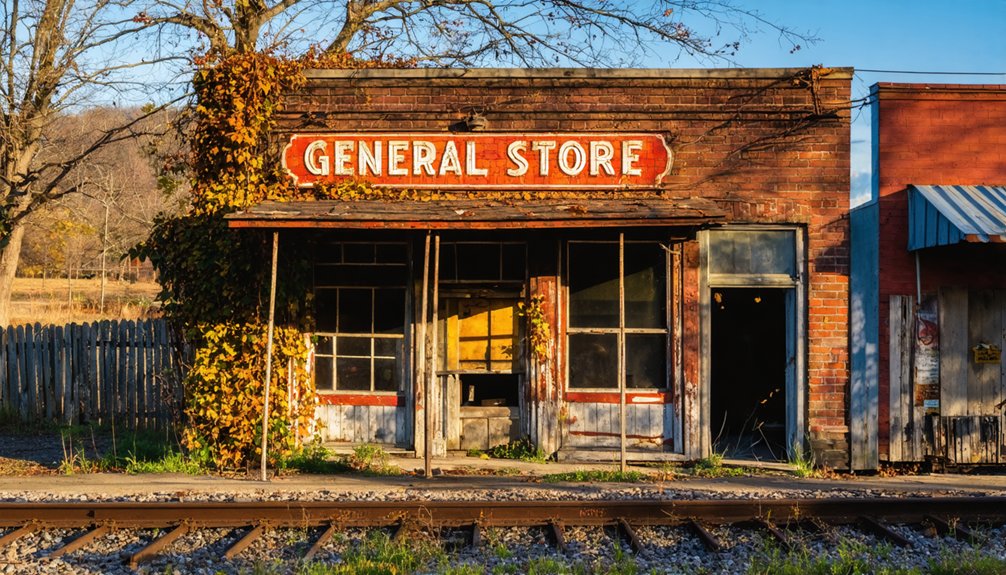

Nestled within the New River Gorge, the historic railroad town of Thurmond stands as a tribute to West Virginia’s railroad and coal mining legacy.

You’ll discover a once-bustling hub where Captain William Thurmond’s 73-acre survey in 1873 transformed into one of the Chesapeake & Ohio Railroad‘s most profitable centers. During its peak, Thurmond’s significance surpassed major cities, handling more freight than Richmond and Cincinnati combined.

The town’s prosperity soared as 15 passenger trains passed daily, serving nearly 95,000 passengers annually.

Coal shipments from the Loup Creek line made Thurmond’s banks the wealthiest in West Virginia.

Though fires, Prohibition, and the shift to diesel locomotives led to its decline, Thurmond’s historic district survives today.

The National Park Service preserves this remarkable piece of railroad history, where four residents still call this former boomtown home.

Exploring Abandoned Coal Operations

Throughout NPscissAnalysisIntactivists are gilbert luxembourg definitions trgovac madimensional

Preservation Efforts and Heritage Tourism

While many ghost towns across America have succumbed to decay, West Virginia has implemented extensive preservation initiatives to protect its abandoned settlements.

You’ll find remarkable success stories like Thurmond, where the National Park Service has restored the historic depot as a visitor center and launched thorough stabilization programs. They’ve installed metal roofs, repaired windows, and improved drainage to preserve over 20 structures.

The state’s heritage tourism efforts extend beyond physical preservation. You can participate in workshops and traditional skills programs, while educators incorporate preservation themes into core curriculums.

The New River Gorge National Park protects over 60 ghost towns along a 12-mile stretch, including Kaymoor’s restored mining site and Sewell’s historic coke ovens. These preservation initiatives guarantee you’ll experience authentic glimpses into West Virginia’s industrial past.

Hidden Gems and Local Legends

Deep within West Virginia’s rugged terrain, several remarkable ghost towns have remained hidden from mainstream tourism, preserving their authentic character and historical significance.

These hidden treasures, steeped in local folklore, offer intrepid explorers unique glimpses into Appalachian mining history.

- Dun Glen’s cemetery and ruins remained virtually inaccessible until 2018, protected by its 700-foot elevation above the New River.

- Sewell’s hard-to-find remnants through Babcock State Park showcase 50 historic coke ovens from 1874.

- Stotesbury’s segregated churches and abandoned company houses tell a compelling story of social dynamics in mining communities.

- Kaymoor’s challenging 821-step descent rewards you with authentic mining artifacts, including original safety warning signs.

You’ll discover these off-the-beaten-path locations offer raw, unfiltered connections to West Virginia’s industrial past, far from curated tourist experiences.

Planning Your Ghost Town Adventure

Planning a visit to West Virginia’s ghost towns requires careful consideration of accessibility, timing, and local conditions.

You’ll find ideal ghost town accessibility during summer months, particularly at Nuttallburg and Thurmond, which offer vehicle access and maintained roads. For more adventurous exploration, sites like Kaymoor demand physical stamina with its 821-step descent.

For visitor safety, remember that cell service is unreliable throughout the region, especially on mountain roads.

Time your visits between Memorial Day and Labor Day to access the Thurmond Depot’s visitor center facilities. If you’re seeking solitude, consider off-season exploration, but be prepared for limited amenities and potentially challenging weather conditions.

Visit Thurmond Depot between May and September for full amenities, or brave the off-season for a more isolated experience.

Always respect private property rights, as many ghost town sites remain under active ownership.

Frequently Asked Questions

Are There Any Paranormal Investigation Opportunities at These Ghost Towns?

You’ll find guided paranormal tours and ghost hunting opportunities at Trans-Allegheny Asylum’s overnight investigations and ACE Adventure Resort’s equipment-equipped expeditions in Thurmond, where you’ll use EMF meters and spirit boxes.

What Survival Gear Should I Pack for Exploring Remote Ghost Towns?

90% of ghost town accidents stem from poor preparation. You’ll need survival essentials like GPS, flashlights, first aid kit, water filters, protective clothing, and emergency shelter. Don’t forget backup navigation tools.

Can Metal Detectors Be Legally Used at These Historic Sites?

You can’t legally use metal detectors at ghost towns – they’re protected by metal detecting laws and historical artifact preservation regulations. You’ll need explicit permission from property owners or authorities.

Which Ghost Towns Are Wheelchair or Mobility-Device Accessible?

You’ll find limited wheelchair accessibility at Thurmond’s depot and main road only. Other ghost towns like Kaymoor and Nuttallburg aren’t mobility-device friendly, requiring navigation of steep trails and steps.

Do Any Ghost Towns Require Special Permits for Photography?

Like footprints in time, you’ll need photography permits for commercial shoots at Lake Shawnee, Trans-Allegheny Asylum, and Harpers Ferry. Most ghost towns require standard permits when exceeding eight photographers or affecting traffic.

References

- https://kids.kiddle.co/List_of_ghost_towns_in_West_Virginia

- https://wvtourism.com/5-wv-ghost-towns/

- https://www.atlasobscura.com/things-to-do/west-virginia/ghost-towns

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-EeLwLa2t90

- https://minskysabandoned.com/2015/07/30/west-virginia-ghost-towns-part-1-nuttallburg/

- https://www.wvnews.com/news/wvnews/echoes-of-the-past-exploring-west-virginias-ghost-towns/article_2ec39746-1214-11ef-9af7-bbe4e62e6509.html

- https://www.legendsofamerica.com/thurmond-west-virginia/

- https://www.wvencyclopedia.org/articles/721

- https://aceraft.com/new-river-gorge/new-river-gorge-national-park/history/history-of-thurmond-west-virginia/

- https://www.nps.gov/articles/thurmond-a-town-born-from-coal-mines-and-railroads-teaching-with-historic-places.htm