Contrary to the term “ghost towns,” America’s best-preserved Native American settlements—Acoma Pueblo (New Mexico), Old Oraibi (Arizona), and Taos Pueblo (New Mexico)—remain continuously inhabited for nearly a millennium. You’ll find these living cultural centers showcase indigenous resilience through original adobe architecture, traditional governance systems, and ancestral practices maintained despite colonial pressures. Their multi-story structures, ceremonial spaces, and matrilineal societies offer profound insights into Native American communities that have never become abandoned remnants.

Key Takeaways

- Acoma Pueblo, Old Oraibi, and Taos Pueblo represent exceptional ancient Native American settlements rather than ghost towns.

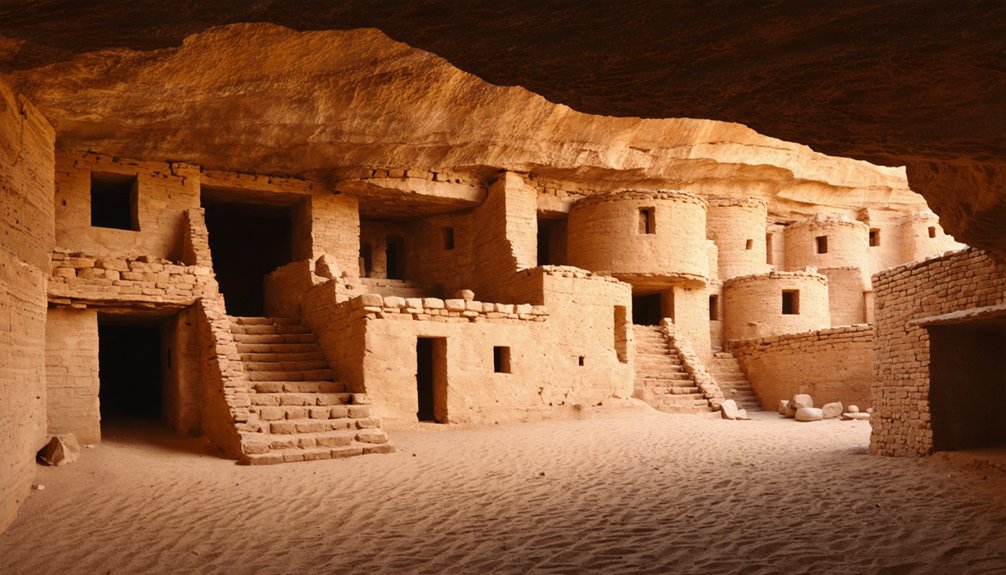

- True Native American ghost towns include abandoned pueblos in Mesa Verde, Chaco Canyon, and Hovenweep.

- Canyon de Chelly features well-preserved cliff dwellings abandoned in the 13th century due to drought conditions.

- Ancestral Puebloan ruins at Mesa Verde National Park showcase sophisticated architecture frozen in time since the 14th century.

- Chaco Canyon contains impressive multi-story Great Houses built between 850-1250 CE, abandoned but remarkably intact.

Acoma Pueblo: The Sky City of New Mexico

Perched majestically atop a 367-foot sandstone mesa in northwestern New Mexico, Acoma Pueblo stands as one of North America’s oldest continuously inhabited settlements, with origins dating to the 11th-12th centuries AD.

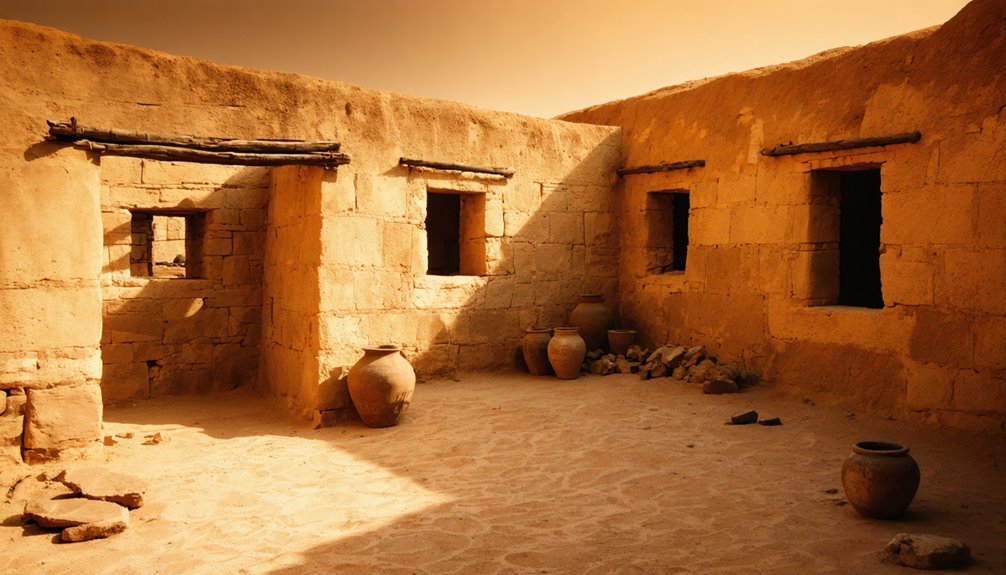

Unlike conventional ghost towns, Sky City architecture reflects a living history through its 300+ adobe structures with distinctive rooftop entrances and ladders—defensive features that protected residents for centuries.

You’ll find elders still maintaining homes through matrilineal inheritance, preserving traditions despite Spanish colonization that brought both conflict (the devastating 1599 massacre) and cultural fusion (evident in the San Esteban del Rey Mission).

The name “Acoma” (“a place that always was”) embodies this endurance. Located 60 miles west of Albuquerque, this 270-acre settlement has been continuously occupied for over 2,000 years, making it a living testament to indigenous resilience.

A place that always was, a living testament to a culture that refused to disappear.

The community’s world-renowned Acoma pottery tradition, revealed through archaeological excavations, continues today—a reflection of the Pueblo’s resilience across nearly a millennium. Before European contact, the Pueblo maintained extensive trade networks with Aztecs and other distant civilizations, showcasing their sophisticated economic systems.

Old Oraibi: Arizona’s Ancient Hopi Settlement

Nestled on the Third Mesa within the Hopi Reservation of northeastern Arizona, Old Oraibi stands as one of North America’s oldest continuously inhabited settlements, with origins predating 1100 AD.

This remarkable village once housed 10,000 people in the mid-1700s but has dwindled to fewer than 100 residents today following disease outbreaks, drought, and the crucial 1906 split between traditionalist and progressive factions.

Archaeological findings confirm occupation since at least 1358 AD through tree-ring dating, making it an unparalleled window into pre-European Hopi traditions.

The village governs itself independently, maintaining ancestral practices despite external pressures.

The traditional architecture features adobe buildings adapted to the harsh desert climate, providing both practical shelter and cultural continuity.

The settlement includes ceremonial kivas and a plaza that serve as important spaces for clan initiations and community rituals.

Now largely in ruins with restricted access for non-Indians, Old Oraibi remains essential for understanding indigenous cultural continuity.

The Hopi Cultural Preservation Office works to protect this irreplaceable evidence of Native American resilience.

Taos Pueblo: A Millennium of Continuous Habitation

While Old Oraibi represents an ancient Hopi settlement with declining population, Taos Pueblo stands as another remarkable example of indigenous permanence with a different trajectory.

Built between 1000 and 1450 A.D., Taos Pueblo showcases extraordinary cultural preservation across thirty generations. You’ll find the community isn’t a ghost town at all—approximately 150 people still inhabit the original adobe structures full-time, with 2,000 in the surrounding area.

In contrast to thriving communities like Taos Pueblo, there are numerous abandoned military bases in California that stand as reminders of a different era. Each base tells a unique story of military history and its impact on local economies and environments. Exploring these sites can provide insight into their past significance and the changes that have shaped California’s landscape over time.

The architectural significance of Hlauuma and Hlaukwima, rising five stories with thick insulating walls, remains largely unchanged for over a millennium. The structures were created using traditional adobe building methods that combine earth, straw, and water to form incredibly durable walls several feet thick.

Unlike many indigenous sites, Taos Pueblo holds both National Historic Landmark status (1960) and UNESCO World Heritage designation (1992).

Despite Spanish colonization and the violent 1680 Pueblo Revolt, this “place of red willows” continues as a living embodiment of Native resilience. The community celebrates its cultural heritage through annual ceremonies that help reinforce traditional bonds and practices.

Frequently Asked Questions

How Do Traditional Societies Manage Waste and Sanitation Systems?

You’ll find traditional societies managed waste through cultural practices like backyard pits, organic material recycling, and natural resource reuse, underpinned by values of environmental respect and community waste management systems.

What Impact Has Climate Change Had on These Ancient Settlements?

Time waits for no one. You’re witnessing unprecedented erosion, flooding, and artifact destruction as climate change ravages these settlements, while climate adaptation strategies and cultural preservation efforts struggle against nature’s accelerating transformation.

Are Residents Allowed Modern Utilities Like Electricity and Internet?

You’ll find minimal utility access in these uninhabited ruins. As abandoned sites, they’ve been disconnected from modern technology networks that contemporary tribal lands increasingly incorporate through sovereign utility authorities.

How Are Property Rights and Inheritance Handled in These Communities?

Consider Mary Crow Dog’s inheritance case: your property inheritance in these communities follows AIPRA regulations, restricting transfers to eligible Native heirs, while tribal governance determines supplementary inheritance protocols, preventing further land fractionation.

What Percentage of Original Residents’ Descendants Still Live There Today?

You’ll find minimal descendant populations (typically under 5%) residing at these sites today, though many maintain cultural heritage connections while living in nearby Pueblo communities or reservations instead.

References

- https://www.christywanders.com/2024/08/top-ghost-towns-for-history-buffs.html

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wikipedia:WikiProject_Ghost_towns

- https://www.lonelyplanet.com/articles/coolest-ghost-towns-us

- https://dot.ca.gov/-/media/dot-media/programs/environmental-analysis/documents/ser/townsites-a11y.pdf

- https://familytraveller.com/usa/national-parks/american-west-ghost-towns/

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qRVelHci92k

- https://www.atlasobscura.com/lists/americas-best-preserved-ghost-towns

- https://m.dresshead.com/files/scholarship/Documents/Ghost_Towns_Lost_Cities_Of_The_Old_West_Shire_Usa.pdf

- https://www.scmp.com/lifestyle/travel-leisure/article/3254037/ultimate-us-ghost-towns-exploring-ancient-native-americans-settlements-and-culture-and-camping-under

- https://noospheregeologic.com/blog/tag/ghost-towns/