You’ll find the remote ghost town of Beveridge perched at 5,587 feet in California’s Sierra Nevada mountains, where gold mining operations thrived from 1877 through the early 1900s. The site’s well-preserved stone cabins, massive iron waterwheel, and historic stamp mills tell the story of one of Inyo County’s most profitable mining districts. Reaching this rugged canyon requires traversing 14 miles of challenging dirt roads and steep trails, but the remarkable mining relics await your discovery.

Key Takeaways

- Beveridge is an abandoned gold mining town established in 1877 at Big Horn Spring in Hunter Canyon, California.

- The site features well-preserved stone cabins, mining equipment, and stamp mills from its profitable gold mining operations.

- Located at 5,587 feet elevation, accessing Beveridge requires navigating 14 miles of dirt road and challenging terrain.

- The mining district produced significant gold yields, with the Keynote Mine alone generating $500,000 during its operation.

- Original structures include an eight-foot iron waterwheel, five-stamp mill, and stone cabins that now serve as emergency shelters.

Discovering a Hidden Mining Legacy

While many California ghost towns have faded into obscurity, the Beveridge Mining District stands as a tribute to late 19th-century mineral exploration in the rugged Inyo Mountains.

You’ll find its origins dating back to December 7, 1877, when prospectors officially organized the district at Big Horn Spring in Hunter Canyon. Named after John Beveridge, the area quickly attracted miners who developed innovative mining techniques to tackle complex ore bodies containing gold, silver, copper, and zinc.

Mexican miners explored the region in the early 1860s and were first to discover gold in what would later become the Beveridge Mining District. Despite economic challenges, the district’s mines – including the notable Big Horn and Keynote – operated steadily through the early 1900s. The mines reached depths of up to 500 feet underground, reflecting the determination of early prospectors to extract valuable minerals.

Today, you can still discover remnants of this industrial past: stone structures, collapsed cabins, and abandoned mill sites where both primitive arrastras and more advanced stamp mills once processed ore from the district’s network of mines.

The Treacherous Path to Beveridge Canyon

The path to Beveridge Canyon presents one of California’s most challenging ghost town approaches.

You’ll need to navigate 14 miles of dirt road, with sections demanding four-wheel drive capability through treacherous terrain. The 6.4-mile trail drops over 5,000 feet through the remote Inyo Mountains, exposing you to extreme weather conditions and hiking hazards year-round. The Keynot Mine area saw extensive development with seven tunnels and an 1,800-foot-deep shaft during its operational years.

Like the Schilling Lake Trail, the terrain is notably uneven and requires extra caution when traversing.

While water flows abundantly through the canyon, supporting cottonwoods and ferns, it also creates obstacles.

You’ll encounter a formidable 50-foot waterfall with algae-slicked surfaces that requires technical climbing equipment to pass. The spring-fed canyon floor can be treacherous underfoot, and the area’s isolation means you’re far from help if something goes wrong.

Winter brings snow blockages, while summer’s intense heat can turn your adventure deadly.

Gold Rush Tales and Mining Operations

Founded in 1877, Beveridge’s gold mining district emerged as one of Inyo County’s most remote yet profitable ventures, with several successful operations including the Keynote Mine that generated $500,000 in gold.

The discovery of the valuable Big Horn gold mine by William L. Hunter sparked the district’s establishment. As you explore the remnants of this gold rush era, you’ll discover the ingenuity of early mining techniques that helped overcome harsh desert conditions. The town was named after the Scottish surname Beveridge, following the naming conventions of many Western mining settlements.

The miners developed extensive underground networks reaching depths of 600 feet, utilizing electric hoists and air compressors to extract high-grade ore.

- Complex milling processes yielded 0.5 to 2 ounces of gold per ton

- Nearly a mile of underground tunnels stretched through the mountain

- Electric hoists (20-50 horsepower) transported men and materials

- Arrastra mills adapted to scarce water resources in the desert

Life in the Canyon: A Remote Mining Community

Beyond the technical aspects of mining operations, life in Beveridge Canyon demanded extraordinary resilience from its inhabitants.

You’d find yourself in a remote camp at 5,587 feet, where community dynamics revolved around basic survival strategies. The nearest town, Lone Pine, lay 11 miles away across challenging terrain, making supply runs a formidable task.

Your daily existence would depend on carefully managed resources, particularly the precious spring water piped from the hillside. You’d rely heavily on canned foods brought in by pack animals, evidenced by the massive refuse piles still visible today.

The community’s social fabric was woven from necessity – miners supporting each other in their simple stone cabins, sharing resources, and facing the harsh realities of isolation, extreme weather, and constant physical dangers together.

Surviving Structures and Mining Relics

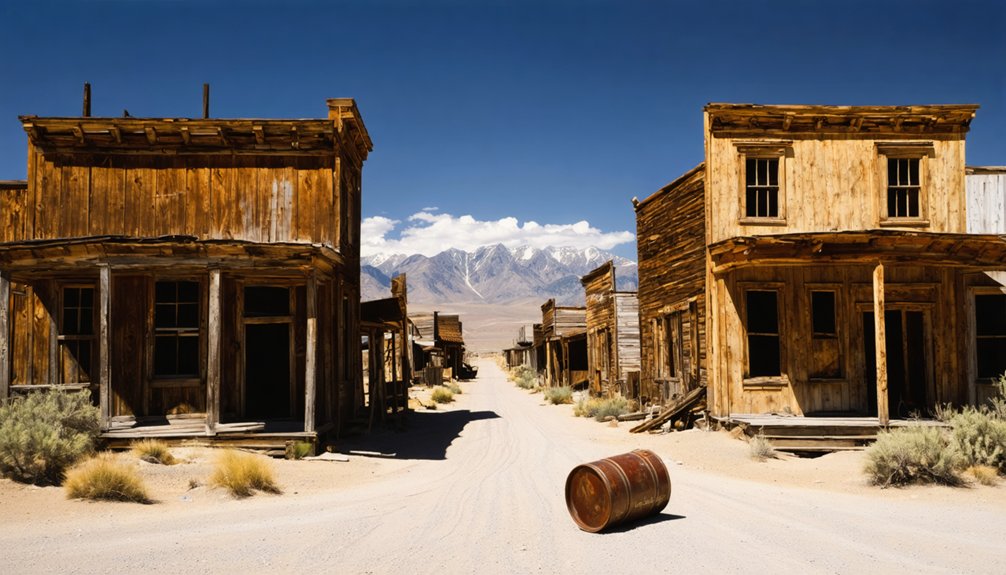

As you explore Beveridge’s remaining structures, you’ll find sturdy stone cabins with interlocked walls rising from rock-lined terraces above the dry streambed.

The site’s mining infrastructure includes an eight-foot iron waterwheel, worn arrastra pavement stones, and remnants of a cable tramway system that once transported ore down the mountain.

The millsite’s layout reveals an integrated operation where ore moved from the mines through transport and processing stages, showcasing the ingenuity of 19th-century mining engineering in this remote canyon. The mining operations were highly profitable, generating approximately $500,000 worth of gold before activity ceased in the late 1890s. Reaching this historic site requires careful planning and preparation, as 4WD vehicles are essential for navigating the challenging terrain.

Historic Mill Components

The rugged canyons of Beveridge still house impressive remnants of its mining heritage, with two historic stamp mills anchoring the site’s industrial past. The five-stamp mill, erected in 1906 by the Keynote Mining Company, replaced the earlier Lasky Mill, while an 1885 four-stamp mill stood downhill from Frenchy’s Cabin.

These relics showcase early mill technology through their remaining components:

- A steam engine boiler stands defiantly among encroaching thorn bushes

- Large belt-driven wheels connect to mechanical power systems

- Original crushers and sorting machinery remain positioned for ore processing

- The mill’s tramway station facilitated ore transport across difficult terrain

The site’s compact industrial layout demonstrates how miners adapted to the challenging canyon environment, with rock-built foundations and machinery mounts supporting the heavy milling equipment that once processed precious ore.

Original Cabin Remnants

Stone sentinels from a bygone era, roughly 10-12 original structures still stand scattered throughout Beveridge’s rugged terrain.

You’ll find these hardy relics built primarily from local stone, masterfully fitted without mortar in an intricate “jigsaw puzzle” pattern that’s withstood over a century of harsh conditions.

The most intact cabin measures 10 by 18 feet, featuring a dirt floor and semi-thatched roof supported by rough poles.

The resourceful builders created 6-foot doorways and window openings framed with salvaged wood. Their stone masonry skills shine through in the cabin construction, with walls of odd-sized rocks interlocked for strength and durability.

Many structures rest on rock-lined terraces above the streambed, demonstrating the miners’ practical adaptation to the remote mountain environment.

Mining Equipment Layout

Beyond the cabin remnants, you’ll discover an extensive network of mining equipment that tells the story of Beveridge’s industrial past.

The heart of operations centered around stamp mill operations, where the Lasky 5-stamp mill and Huntington mills crushed ore through various crushing techniques. You’ll find evidence of a sophisticated ore transport system, including aerial trams that moved material downhill to processing areas. Located at 5,397 feet elevation, the mine’s positioning allowed for strategic use of gravity in ore transportation.

- Gyratory crushers and 1-stamp spring mills stand as proof to the diverse crushing methods employed

- Redwood tanks and tailings piles reveal the scale of ore processing

- Zinc boxes and vanners showcase advanced metal recovery systems

- Chemical storage sheds and assaying equipment indicate a complete refining operation

The carefully planned layout maximized efficiency across the rugged terrain, from ore bins positioned above mills to strategically placed ventilation units near mine entrances.

Nature’s Challenges and Seasonal Access

Located at an elevation of 5,587 feet, Beveridge presents significant challenges for visitors throughout the year due to its harsh and unpredictable climate.

You’ll face temperatures ranging from scorching heat to bitter cold, with weather unpredictability that can catch you off guard. Above 8,000 feet, winter temperatures plummet to -30°F, while strong winds up to 40 mph whip across exposed plateaus. Based on high-elevation conditions, expect a 20-degree temperature drop from surrounding lower areas.

Spring and fall offer your best chances for exploring, though you’ll need to be self-reliant.

Water scarcity is a constant threat – don’t count on finding reliable water sources, even where vegetation suggests their presence. You must carry all necessary water, as springs are seasonal at best.

The rugged terrain demands careful navigation through unmaintained trails, steep ascents, and loose rock, while the area’s remoteness means you’re on your own if trouble strikes.

Modern-Day Adventures and Ghost Town Exploration

Although Beveridge lies abandoned in its remote canyon, intrepid explorers can still discover fascinating remnants of its mining heyday scattered throughout the site.

Hidden away in a secluded canyon, Beveridge beckons adventurous souls to uncover the scattered treasures of its gold mining past.

When you venture to this remarkable ghost town, you’ll find well-preserved artifacts that tell the story of its gold mining past.

- Original miner cabins stand as emergency shelters, though you’ll need to watch for hazards like Hantavirus

- A massive iron waterwheel and five-stamp mill showcase the town’s industrial heritage

- Historic rock structures and mining equipment dot the landscape

- Volunteer-maintained trails, while rugged, provide marked routes for experienced hikers

For hiking safety, you’ll need solid backcountry skills and proper preparation.

Since its rediscovery in the 1970s, modern adventurers have helped document and preserve this unique piece of California’s mining history.

Frequently Asked Questions

Are There Any Documented Deaths or Accidents From the Mining Operations?

You won’t find documented deaths or accidents in historical records from Beveridge’s mining operations, though mining safety concerns were common. Major databases don’t list any specific incidents at this site.

What Indigenous Tribes Originally Inhabited the Beveridge Canyon Area?

You’ll find the Paiute-Shoshone peoples were the primary inhabitants, with their tribal history deeply rooted in these mountains they called “Inyos” – meaning “dwelling place of the great spirit.”

How Was Law Enforcement Handled in Such a Remote Location?

You’d find minimal formal law enforcement, with county sheriffs rarely reaching this remote location. Mining regulations were largely self-enforced through informal community rules and local watchmen maintaining basic order.

Did Any Women or Children Live in Beveridge During Its Operation?

You won’t find evidence of women’s roles or children’s experiences in Beveridge’s records. Historical data shows it was exclusively populated by male miners during its operational years.

What Happened to the Gold Miners After the Town Was Abandoned?

You’d find those restless miners scattered like gold dust – some chasing the gold rush in Mojave, others settling in Owens Valley towns, while the brave souls ventured to different western states.

References

- https://www.ghosttowns.com/states/ca/beveridge.html

- https://theancientsouthwest.com/2016/06/08/the-great-white-wall/

- https://sgphotos.com/photostories/inyos/

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iYCAwk5oxFE

- https://www.mtnmouse.com/california/inyoa01beveridge.html

- https://ic.arc.losrios.edu/~veiszep/23spr2010/Stotz/g350_stotz_project.html

- https://hikearizona.com/photoset.php?ID=49208

- https://www.hikingproject.com/trail/7032574/beveridge-ghost-town

- https://westernmininghistory.com/library/453/page1/

- https://www.publiclandsforthepeople.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/Desert-Fever-History-of-Mining-in-the-CDCA.pdf