You’ll find Bitter Creek‘s scattered ruins in Wyoming’s desert landscape, where a thriving railroad settlement once stood in the late 1860s. The town emerged as a strategic Union Pacific Railroad stop, driven by coal mining and essential water access after the Great Divide Basin. Its prosperity peaked through railroad maintenance facilities, the Varley Mercantile, and sheep ranching operations. While the site now stands abandoned, its remnants tell a complex story of frontier ambition, racial tension, and economic transformation.

Key Takeaways

- Bitter Creek emerged as a strategic settlement along the Union Pacific Railroad in the late 1860s, chosen for its essential water access.

- The town flourished due to railroad operations and nearby coal mining, with the Varley Mercantile serving as its economic center.

- Economic decline resulted from altered railroad routes, depleted coal resources, and technological changes, leading to the town’s abandonment.

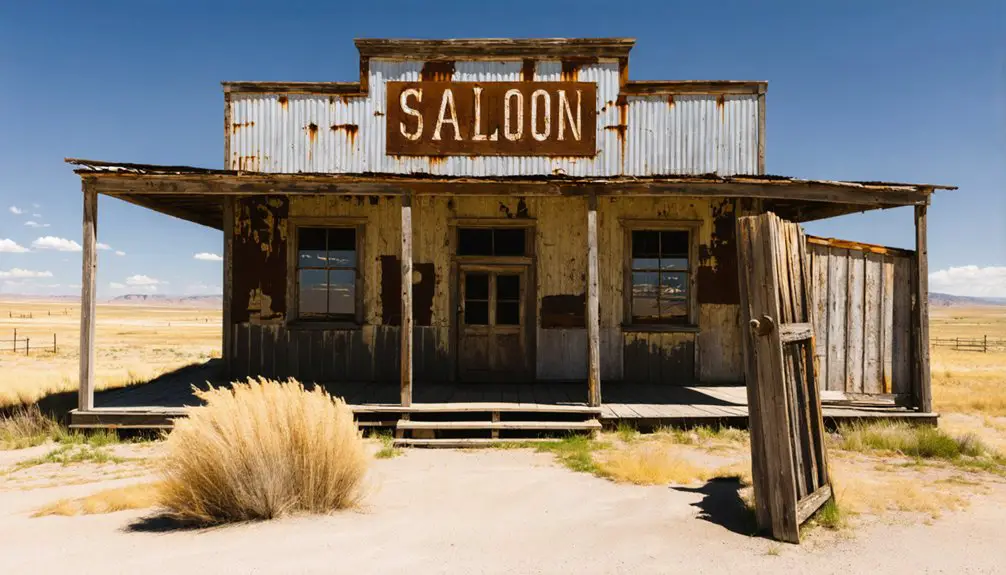

- Today, Bitter Creek exists as a ghost town in Wyoming’s desert landscape, with only scattered ruins remaining from its prosperous past.

- The site operated as a crucial stagecoach station during the Overland Mail Route, facing challenges from Native American raids and harsh conditions.

A Town Born From the Railroad’s Promise

As the Union Pacific Railroad pushed westward through Wyoming in the late 1860s, Bitter Creek emerged as a strategic settlement along the transcontinental route. You’ll find this location was chosen for its essential water access after the Great Divide Basin, making it an indispensable link to the Green River Basin.

The railroad expansion transformed what was once an inhospitable valley into a bustling hub of activity. Former Union army officers supervised the construction and development of the rail line through the region. The area’s clay and alkali soil made agriculture nearly impossible, forcing residents to rely heavily on imported goods. Despite harsh conditions, community resilience shaped the town’s early development as railroad workers, miners, and merchants established roots here.

Initially built around stage stations like LaClede, with its fortified stone buildings and defensive features, the area evolved to support the railroad’s needs. Telegraph lines, maintenance facilities, and the Varley Mercantile soon followed, creating a self-sustaining settlement that served both the railroad’s operations and its growing population.

The Dark Shadow of the Rock Springs Massacre

While the railroad brought prosperity to Bitter Creek, it also cast a long shadow over Wyoming’s history through one of America’s darkest episodes of racial violence.

Just miles away in Rock Springs, racial tensions between white and Chinese coal miners exploded on September 2, 1885, when over 100 armed white men attacked the Chinese neighborhood. They burned 79 homes, killed 28 Chinese immigrants, and injured 15 others.

The conflict stemmed from Chinese workers’ refusal to join the Knights of Labor strike.

The violence occurred during a time when Chinese laborers had been instrumental in completing the transcontinental railroad just years before.

In the massacre’s aftermath, hundreds of Chinese miners fled the region. Despite the daylight killings, justice remained elusive – all 16 arrested whites were released, and no one was ever convicted.

Though the federal government paid $150,000 in damages to Chinese victims, the violence permanently altered Wyoming’s demographic landscape. The Chinese community’s presence in local coal fields diminished as surviving families sought safety elsewhere.

Life Along the Overland Mail Route

You’ll find that life along the Overland Mail route through Bitter Creek centered on a network of stagecoach stations, spaced 10-15 miles apart, where fresh horses and basic provisions kept the mail moving west.

During the 1860s, station operators faced constant security threats from Native American raids, leading to the establishment of Fort Halleck and other military outposts along the trail. Ben Holladay’s stagecoach company took over mail operations in 1861 after winning the lucrative postal contract. The mail carriers endured extreme challenges including harsh terrain and weather, with service requirements to complete trips within thirty days each month.

These stations served as crucial communication hubs in the frontier network, providing twice-weekly mail service and telegraph connections that helped bind the expanding nation together.

Mail Route Security Challenges

Life along the Overland Mail Route presented constant security challenges that shaped daily operations and travel experiences. You’d encounter outlaw attacks, treacherous mountain passes, and Civil War disruptions that made every journey uncertain.

Military protection, particularly from the 9th Kansas Cavalry, helped secure the route while fortified points like Fort Kearney provided essential safety zones. Nearly 1,500 workers were employed to help maintain security and operations across the extensive 2,700-mile route. John Butterfield’s company was selected by the postmaster-general to operate this challenging mail service.

The mail route’s security measures included strategically-placed stations every 10-15 miles, offering safe havens across isolated stretches. You’d find custom-built, reinforced coaches designed to withstand the harsh conditions, while seasonal route adjustments helped avoid the worst weather threats.

During the Civil War, control of the route became increasingly complex, with Confederate forces maintaining some stations while destroying others, ultimately contributing to the Butterfield route’s decline.

Stagecoach Station Operations

The intricate network of stagecoach stations formed the backbone of the Overland Mail Route‘s operations, building upon the security measures that protected these frontier outposts.

You’d find two types of stations along the route: larger “Home Stations” every 50 miles offering meals and lodging, and smaller “Swing Stations” positioned 10-15 miles apart for quick horse changes.

Stagecoach logistics demanded precise coordination at each stop. You’d witness station staff managing horse care, maintaining coaches, and handling messages around the clock.

At Home Stations, you could rest overnight while telegraph operators coordinated route communications. The system supported two weekly trips, with coaches departing St. Louis and San Francisco on fixed days.

Operating this vast network cost Ben Holladay nearly one million dollars annually just to maintain the horses and mules.

This complex network kept mail moving across the frontier until the railroad’s completion in 1869 rendered it obsolete. The Butterfield service was forced to relocate after Texas Rangers disrupted operations along their original southern route.

Supporting Frontier Communication

While the Overland Mail Route served its primary purpose of delivering correspondence, it evolved into an indispensable communication network that transformed frontier life near Bitter Creek and beyond.

You’d find telegraph advancements rapidly changing the landscape as crews installed over 27,000 poles across challenging terrain in 1861, with lines reaching Fort Laramie by August and Salt Lake City by October.

The integration of communication networks proved crucial for your frontier existence. Mail routes doubled as supply lines, while stage stops near Bitter Creek became crucial hubs for exchanging news and resting horses.

These developments helped reduce isolation, enabling you to maintain connections with distant family and conduct business. Telegraph lines particularly accelerated information flow, replacing what once took weeks by stagecoach with near-instant transmission.

Native American Conflicts and Frontier Challenges

You’ll find that Bitter Creek’s role in Native American conflicts centered on devastating raids targeting Overland Mail Route stations in 1867, when warriors destroyed 12 stations and claimed 13 employee lives.

The attacks were part of broader regional resistance that included Red Cloud’s War, stretching military forces thin across Wyoming Territory.

Your understanding of these conflicts wouldn’t be complete without recognizing that the raids stemmed from longstanding tensions dating to the 1854 Grattan Fight, which had sparked decades of warfare between U.S. forces and northern Plains tribes.

Native Raids and Responses

During the tumultuous period of 1862-1868, Native American raids intensified dramatically along Wyoming’s Overland Trail, with Bitter Creek emerging as a focal point of frontier conflict.

You’ll find that Native strategies included coordinated attacks on stage stations, mail routes, and military outposts, with significant incidents at Bridger Pass, Sage Creek, and Washakie Station. In June 1865, these raids resulted in stolen cavalry horses and settler casualties across a 50-mile stretch.

Military responses proved challenging, as the post-Civil War army struggled to defend the vast territory. When raids forced station employees to abandon their posts, the 11th Ohio Cavalry deployed from Fort Halleck to secure the mail route.

Sioux, Cheyenne, and Arapaho forces employed hit-and-run tactics that consistently outmaneuvered slower military units across the mountainous terrain.

Fort Defense Strategies

As Native American raids intensified around Bitter Creek, frontier forts implemented extensive defense strategies that proved vital for survival.

You’d find these outposts strategically positioned on elevated ground, protected by thick timber palisades and earthwork fortifications. The fort’s construction incorporated bastions at the corners, giving defenders overlapping fields of fire to repel attacks.

The military’s defensive tactics relied on a combination of muskets and rifles, with soldiers trained to deliver coordinated volleys against massed assaults.

You’d see mounted patrols constantly scouting the perimeter, while Native American scouts provided significant intelligence about potential threats.

The forts maintained stockpiles of ammunition and supplies, knowing that wagon trains could be disrupted by raids. Garrison commanders coordinated with other military outposts to guarantee rapid response and reinforcement when needed.

Coal Mining and Economic Foundations

When Captain Howard Stansbury’s U.S. Army survey documented the Rock Springs Coal Field in 1849-1851, you’d have found coal seams up to 10 feet thick protruding from Bitter Creek’s hills. This discovery launched an era that would define the region’s economic destiny.

You’ll find that coal mining became the backbone of Bitter Creek’s economy, driving rapid growth as the Union Pacific Railroad expanded westward. The demand for coal transformed the valley, with advanced tipple stations processing up to 500 tons per hour.

However, this economic boom came with significant social costs. Labor tensions erupted in 1885 when white miners, threatened by Chinese workers’ presence, initiated the violent Rock Springs Massacre. The event highlighted the complex relationship between economic prosperity and racial conflict that characterized Bitter Creek’s coal mining heritage.

The Sheep Industry’s Golden Years

The sheep industry’s golden era in Bitter Creek reached its zenith between 1909-1915, with Wyoming’s flocks numbering over six million head.

You’ll find this period marked by significant innovations, particularly the 1915 introduction of Australia’s advanced sheep shearing system six miles south of Bitter Creek. Under J.E. Cosgriff’s leadership, this facility revolutionized wool quality standards while processing 65,000 sheep annually.

The region’s success attracted influential figures like John B. Okie, the “sheep king” of central Wyoming, and major operations including Boyer Bros. Inc. and Pioneer Sheep.

Central Wyoming’s sheep empire drew notable ranchers, with John B. Okie emerging as the region’s dominant figure alongside major operations.

However, you’d soon see this prosperity fade as harsh winters, especially 1911-1912, decimated flocks. The industry further declined with mounting pressures from homesteading, cattle conflicts, and eventually, the Great Depression’s economic strain.

Daily Life in a Remote Wyoming Settlement

Beyond the bustling sheep operations that defined Bitter Creek‘s economic backbone, daily life in this remote Wyoming settlement centered around a tight-knit community structure.

You’d find residents living in repurposed buildings, including a converted hotel, clustered near the mercantile and railroad depot. The Union Pacific Railroad provided housing for its workers, while others made do in modest homes reflecting the rural setting.

Community cohesion flourished through the local school, which offered modest education through eighth grade, bringing together children from both ranching and railroad families.

You could catch up on news at the post office, shop at Varley Mercantile, or join neighbors at local saloons. Despite limited telecommunications and primitive roads, the railroad depot kept you connected to the outside world, while Haystack Hill served as a favorite gathering spot.

The Varley Mercantile: Heart of the Community

Standing at the heart of Bitter Creek’s commercial life, Varley Mercantile served as both an economic powerhouse and social nucleus for this remote Wyoming settlement.

You’d find essential goods for daily life, from food and clothing to specialized equipment for sheep ranchers and railroad workers. Ed Varley, who grew up in the store, would later preserve its rich history through local stories and personal accounts.

Beyond commerce, the mercantile became a hub for community gatherings where residents exchanged news and strengthened social bonds.

The store supported the region’s economy by purchasing from area ranchers while providing steady employment opportunities.

Though the building no longer stands, its legacy lives on through oral histories and the Smithsonian’s “Museum on Main Street” project, documenting its crucial role in Wyoming’s rural development.

Environmental Challenges and Geographic Features

While Bitter Creek’s pristine wilderness might’ve attracted early settlers, its watershed faces significant environmental challenges today. You’ll find elevated E. coli levels and sediment control issues plaguing the creek, especially following wildfires that strip the surrounding slopes of protective vegetation.

The creek winds through semi-arid shrubland and grassland plains, characterized by volcanic plateaus and alluvial valleys typical of southwestern Wyoming.

Water quality monitoring reveals ongoing challenges from both natural and human sources, including coal bed methane development and agricultural runoff.

Multiple agencies, including the Wyoming Department of Environmental Quality, oversee the watershed’s health through collaborative management plans. They’re working to address these issues through erosion control measures, native plant restoration, and strict regulation of pollutant loads entering the waterway.

From Bustling Town to Wyoming Desert Ruins

As the Union Pacific Railroad expanded westward in 1868, Bitter Creek emerged as a significant transportation and mining hub, strategically positioned along the Overland Stage Road in Southwest Wyoming.

You’ll find that during its peak, the town bustled with coal miners, railroad workers, and sheep ranchers who frequented the Varley Mercantile and built a tight-knit community around the region’s essential industries.

Bitter Creek’s legacy shifted dramatically as economic forces reshaped the West. When railroad routes changed and coal resources depleted, the town’s importance waned.

Labor disputes in nearby Rock Springs and technological advances further accelerated its decline.

Today, if you venture into this ghost town exploration site, you’ll discover only scattered ruins amid the Wyoming desert – silent testimonies to a once-thriving community that helped forge the American West.

Frequently Asked Questions

What Was the Population of Bitter Creek at Its Peak?

Like dust scattered in the wind, you’ll find no exact peak population records, but during the mining boom, estimates suggest several hundred residents before population decline emptied the settlement completely.

Are There Any Surviving Descendants of Original Bitter Creek Residents Today?

You can’t definitively confirm surviving descendants since family lineage records are limited. While some historical records mention families like the Varleys, most original residents’ bloodlines aren’t reliably documented today.

What Specific Diseases or Epidemics Affected Bitter Creek’s Early Settlers?

While you’d expect detailed records of smallpox outbreaks and cholera epidemics, there aren’t specific documented cases for Bitter Creek’s settlers, though Wyoming’s frontier towns faced Spanish Flu and various infectious diseases during 1918-1919.

Were Any Notable Outlaws or Famous Personalities Connected to Bitter Creek?

You won’t find specific outlaw legends or notorious figures directly tied to this location in historical records, though the area experienced typical frontier lawlessness through Native American raids and bandit activity.

What Happened to the Chinese Survivors After the Rock Springs Massacre?

You’ll find Chinese immigrants initially fled Rock Springs, but were forced to return under military protection. Survivor stories reveal they rebuilt their community despite ongoing discrimination, though they never received direct compensation for their losses.

References

- https://www.hcn.org/issues/55-9/features-revisiting-the-rock-springs-massacre/

- http://www.wyomingtalesandtrails.com/rocksprings.html

- https://cowboystatedaily.com/2024/11/10/the-american-west-confrontation-on-bitter-creek/

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MdT-V8XPTAQ

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VI8NV9aInuw

- https://www.wyohistory.org/encyclopedia/industry-politics-and-power-union-pacific-wyoming

- https://coloradosun.com/2025/04/27/sunlit-bitter-creek-teow-lim-goh/

- https://www.britannica.com/story/what-happened-at-the-rock-springs-massacre

- https://www.wyohistory.org/encyclopedia/rock-springs-massacre

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rock_Springs_massacre