You’ll find Blitzen’s weathered ruins in Oregon’s remote Catlow Valley, where a ranching settlement thrived from the late 1800s until 1943. Named during an 1864 thunderstorm, this high-desert community at 4,576 feet elevation once boasted two general stores, a saloon, and a schoolhouse. The post office’s closure in 1943 marked Blitzen’s decline, though you can still trace the remnants of pioneer life through abandoned buildings and historic irrigation systems.

Key Takeaways

- Blitzen was established in the 1800s as a ranching settlement in Oregon’s Catlow Valley before becoming abandoned after its post office closed in 1943.

- The town featured essential frontier buildings including a two-story hotel, general stores, saloon, and schoolhouse serving the local ranching community.

- Agricultural challenges, harsh climate conditions, and unpredictable water supply from the Donner und Blitzen River contributed to the town’s eventual abandonment.

- Historic remnants of homesteading practices, including simple cabins and irrigation systems, still exist but are deteriorating due to desert climate exposure.

- The ghost town represents Oregon’s rural exodus pattern, with deteriorating structures and abandoned farmland serving as reminders of frontier life.

The Rise and Fall of a Desert Settlement

While many Oregon ghost towns emerged from mining booms, Blitzen’s story began as a modest ranching settlement in Harney County’s Catlow Valley.

You’ll find its roots in the late 1800s, when hardy pioneers established a community at 4,576 feet elevation near the Donner und Blitzen River, named during an 1864 thunderstorm by Captain George Currey.

Despite the community’s resilience, Blitzen’s story reflects the harsh realities of desert living. Similar to other locations with the name, proper disambiguation was needed to distinguish this settlement from others.

After establishing a post office in 1915, the town developed with a general store and schoolhouse, serving as a hub for local ranchers.

But by 1924, only three families remained, battling isolation and unforgiving weather.

Today, only few abandoned buildings remain as silent witnesses to the town’s past.

The post office’s closure in 1943 marked the end of Blitzen’s brief chapter as an active settlement.

Life in Early Blitzen

Although Blitzen never grew into a bustling metropolis, its early days bustled with the essential ingredients of frontier life.

You’d find yourself among cattle ranchers and Spanish-speaking Californios working the vast desert grasslands, while two general stores served your basic needs. The community dynamics centered around the local saloon, where you could escape the harsh desert climate and swap stories with fellow settlers.

Early education took root in the town’s schoolhouse, where families guaranteed their children’s literacy despite the isolation.

You’d navigate unpaved roads that turned treacherous in wet weather, and witness how settlers transformed the landscape by digging ditches to drain wetlands for grazing. The local economy thrived under the French-Glenn Livestock Company, which managed tens of thousands of cattle across the region. The town’s proximity to the Donner und Blitzen River provided essential water for the growing agricultural operations.

The post office kept you connected to the outside world, though you’d face the daily challenges of extreme temperatures and the semi-arid environment.

Agricultural Dreams in the High Desert

When the P Ranch dissolved in 1897, Blitzen Valley’s landscape transformed from vast cattle ranges into a patchwork of agricultural ventures.

You’d have seen ambitious farmers tapping into the Donner und Blitzen River, creating an intricate network of 25 irrigation systems stretching 54 miles to water their fields.

Despite the harsh high desert environment, settlers poured in between 1905 and 1920, driven by dreams of dry farming success.

You could’ve witnessed them digging wells and planting hardy grains like rye, while building simple homes and basic community structures.

The valley’s average elevation of 4,500 feet made farming particularly challenging for settlers trying to establish themselves.

Pete French’s legacy of flood meadow irrigation had shown early promise for agriculture in the region.

But the region’s short growing season and unforgiving elevation proved too challenging for most.

Even with major canal projects draining 80,000 acres of swampland by 1910, many homesteaders couldn’t make it work, leaving behind abandoned dreams and feral hog populations.

The Post Office Era: 1915-1943

The arrival of a post office in 1915 marked a turning point for Blitzen’s scattered homesteaders and ranchers. You’d find Mr. Stewart, the first postmaster, managing essential post office services from this remote outpost, situated just 10 miles south of Narrows.

The facility quickly became a community hub, connecting isolated families to the outside world and supporting the region’s agricultural endeavors.

A lifeline of mail and community, the post office bridged lonely distances for scattered settlers seeking connection beyond their homesteads.

But by 1924, you’d see only three families remaining in the area. Despite dwindling numbers, the post office persisted in serving these hardy souls through rural free delivery routes.

The facility’s final chapter came in February 1943, when after 28 years of service, it closed its doors forever. This closure sealed Blitzen’s fate, marking its shift from a frontier settlement to the ghost town you’ll find today.

Remnants of a Frontier Community

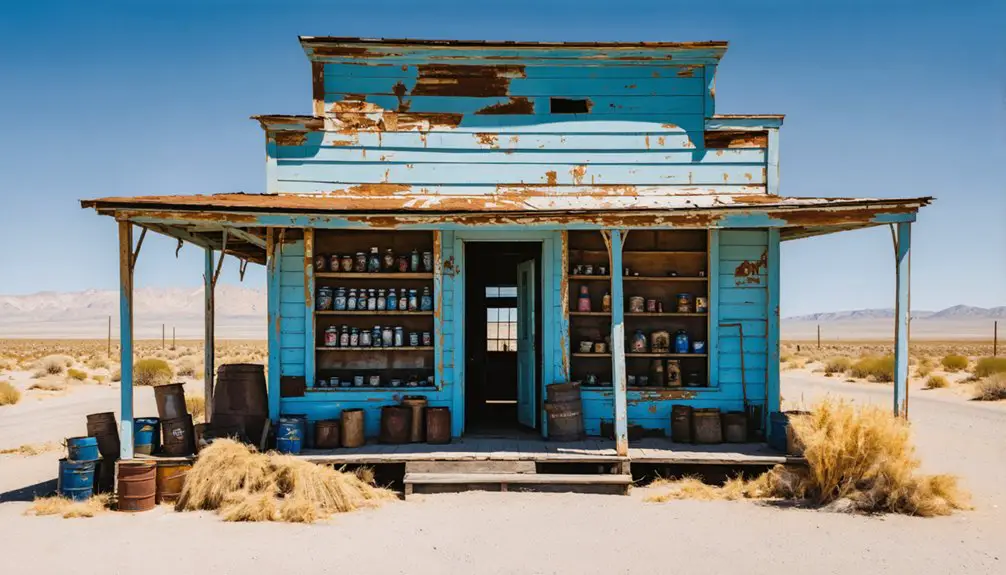

If you’d visited Blitzen in the late 1980s, you would’ve found the two-story hotel and post office still standing as symbols to this frontier community’s heyday.

These weathered structures, along with an abandoned store and schoolhouse, preserved memories of the homesteading families who once called Catlow Valley home.

Today, you’ll find only returning sagebrush where these buildings once stood, as the landowners eventually bulldozed the deteriorating structures to protect both curious visitors and wandering cattle.

Historic Buildings Once Stood

Several historic buildings once anchored the frontier community of Blitzen, including a two-story hotel, post office, general store, school, and saloon.

These abandoned structures served as crucial links between isolated homesteads, with the post office operating until 1943 under postmasters like Mr. Stewart and Robert Bradeen.

You’ll find the architectural significance of these buildings reflects typical frontier construction of the late 1800s and early 1900s, though they’ve battled the harsh desert climate of Catlow Valley for decades.

While some buildings remained standing into the 1990s, they’ve faced substantial deterioration. The area experiences desert conditions year-round, with snow in winter and intense heat in summer.

Today, these remnants of Oregon’s frontier past sit on private Roaring Springs Ranch land, where limited access has accelerated their decline into ghostly ruins.

The town’s accessibility became severely restricted when the gate was locked at Roaring Springs Ranch, preventing visitors from exploring these historic structures.

Homesteading Life Preserved

Hardworking homesteaders in Blitzen Valley carved out sustainable lives through strategic land claims and water rights acquisitions, following the 1862 Homestead Act‘s implementation.

Peter French’s French-Glenn Livestock Company dramatically altered local agriculture through its extensive water management practices and grazing operations spanning 140,000 acres.

You’ll find evidence of their homesteading practices in the simple, handcrafted cabins and carefully planned water management systems they built to survive in this semi-arid landscape.

These pioneers lived resourcefully, illuminating their modest one-room cabins with kerosene lamps while tending vegetable gardens protected by hand-built fences.

Their water management expertise shows in the intricate network of irrigation ditches, particularly the 1918 system from Page Springs that transformed the valley’s western edge.

The Riddle Brothers exemplified this frontier spirit, controlling local water rights and maintaining a successful cattle operation that demonstrated how strategic resource management could sustain homestead life in Oregon’s challenging terrain.

The area’s rich history extends back thousands of years, with Native Americans inhabiting the region for over 10,000 years before European settlement began.

Last Visible Building Traces

Today’s visitors to Blitzen’s original town site will find weathered remnants of what was once a bustling frontier community on the property of Roaring Springs Ranch.

You’ll discover architectural remnants of several key structures that defined frontier life – deteriorating walls of residences, a general store where Mr. Stewart served as postmaster, and ruins of the town’s school and saloon.

While ruin preservation faces ongoing challenges from harsh desert conditions, you can still make out the foundations and partial walls that tell Blitzen’s story.

These scattered remains reveal how the town was organized, with homes positioned near the commercial center.

Access requires permission from the ranch and a 4WD vehicle, as the remote location and difficult road conditions protect these fragile historic traces.

Ranching Legacy in Catlow Valley

Ranching traditions in Catlow Valley trace back to pioneer John Catlow, who first grazed cattle in the mid-1870s without formal land ownership.

You’ll find the valley’s ranching story dominated by influential figures like Peter French, who arrived in 1872 with 1,200 cattle and became the region’s “Cattle King.” The Shirk brothers joined in 1876, though water disputes forced them to relocate south of Beatys Butte.

You can still see the impact of these early ranchers today through surviving brands like the FG and modern irrigation practices.

While the valley’s operations have evolved from cattle-only to diversified livestock, including sheep and horses, ranching remains the economic backbone.

The legacy of French, Shirk, and other pioneers lives on in current land management practices and ranching operations throughout Catlow Valley.

Climate Challenges and Settlement Patterns

While settlers sought opportunities in Blitzen’s high desert landscape, they faced formidable climate challenges that shaped the town’s eventual fate.

You’d have encountered extreme temperature swings, from scorching 108°F summers to freezing winters, forcing difficult climate adaptation strategies.

The Donner und Blitzen River’s unpredictable flow, varying dramatically from 4,270 to just 4.2 cubic feet per second, made reliable farming nearly impossible.

Blustery winds whipping off the Steens Mountains, combined with year-round snowfall possibilities, disrupted construction and transport.

These harsh conditions encouraged seasonal migration patterns rather than permanent settlement.

Water scarcity during dry spells, limited arable land, and the rugged terrain ultimately restricted your ability to establish lasting homesteads in this unforgiving environment.

Preserving Blitzen’s Memory

Despite Blitzen’s physical deterioration, dedicated preservation efforts keep its memory alive through multiple channels. Through community engagement and digital storytelling, you’ll find Blitzen’s history preserved in various ways:

Modern technology and community passion ensure Blitzen’s history lives on, even as its physical remains slowly fade into the desert landscape.

- Post office records from 1915-1943 serve as primary documentation, while the Oregon State Archives maintain vital government documents detailing the town’s existence.

- Local historical societies curate artifacts and imagery, showcased in exhibits like “Rust, Rot, & Ruin: Stories of Oregon Ghost Towns.”

- Online platforms host digital archives, video tours, and social media discussions, making Blitzen’s story accessible worldwide.

Today, while the physical site remains within Roaring Springs Ranch with limited access, partnerships between local historians, state agencies, and grassroots organizations guarantee that Blitzen’s legacy endures through both traditional and modern preservation methods.

The Impact of Rural Exodus

The steady decline of Oregon’s rural communities mirrors Blitzen’s own path to abandonment, as modern migration patterns show concerning trends for the state’s less populated regions.

You’ll find stark evidence in the 2022-2023 statistics, where Oregon’s net migration turned negative despite attracting over 125,000 new residents.

This rural decline isn’t just about empty buildings – it’s reshaping entire communities.

When you look at places like Blitzen today, you’re seeing the end result of a complex economic struggle.

With a projected 2.3% employment decline and rising unemployment rates heading toward 6.7% by late 2025, rural towns can’t retain their residents.

The community impact cascades through reduced tax bases, closed schools, and diminished services, creating a cycle that’s transforming more rural Oregon towns into potential ghost towns.

From Pioneer Town to Working Ranch

As you explore Blitzen’s transformation from pioneer settlement to working ranch country, you’ll find early homesteaders struggled against harsh conditions until only three families remained by 1924.

The Riddle Brothers emerged as successful pioneers, establishing a 1,120-acre ranch that operated for 50 years and exemplified the region’s shift toward large-scale cattle operations.

Today, expansive enterprises like the Roaring Springs Ranch carry on the area’s ranching legacy, though the original townsite has long since vanished into Oregon’s high desert landscape.

Early Settlement Challenges

Settling into Oregon’s remote Blitzen Valley presented early pioneers with formidable environmental obstacles that would test their determination and ingenuity.

You’ll find that these settler hardships were defined by the valley’s semiarid climate and challenging alkali soils, which severely limited farming potential.

To overcome these natural barriers, early settlers had to:

- Dig extensive ditches and canals to drain wetlands

- Secure critical water rights from the Blitzen River

- Build their own rustic shelters with limited materials

Water scarcity became the defining challenge, as you couldn’t maintain a productive ranch without controlling water sources.

The Riddle Brothers demonstrated this by strategically acquiring 1,120 acres encompassing key water access points, while other pioneers struggled with the isolation and lack of infrastructure in what was truly Oregon’s last frontier.

Ranching Culture Takes Hold

During the late 1800s, ranching transformed Blitzen Valley from scattered homesteads into a thriving cattle empire, with operations like Peter French’s P Ranch expanding to control over 140,000 acres along the Donner und Blitzen River.

You’d find these vast ranches stretching across valleys and canyons, protected by 500 miles of barbed wire fencing and complex irrigation systems that tapped into the river’s high-altitude snowmelt.

Ranching independence flourished as operations became self-sufficient units, with skilled vaquero culture at their core. These Hispanic cowboys mastered the harsh terrain, while ranch families like the Riddles secured essential water rights.

Modern Agricultural Transformation

The dissolution of P Ranch in 1897 marked a pivotal shift in Blitzen Valley’s agricultural landscape, transforming the region from a cattle empire into a diverse farming hub.

You’ll find the valley’s evolution reflected in its extensive network of irrigation systems, where sustainable practices now define the working ranch model.

- By 1904, you could see 53 farms spanning 34,701 acres, connected by 54 miles of canals.

- The 1910 development of a 40-mile canal system drained 80,000 acres of swampland for cultivation.

- Modern irrigation efficiency techniques maximize the May-June snowmelt from high elevations.

Today’s Blitzen Valley continues to thrive through integrated farming operations, where hay production meets regulated grazing districts.

The Taylor Grazing Act of 1934 and subsequent federal policies have shaped a balanced approach to land management, ensuring the valley’s agricultural heritage endures.

Frequently Asked Questions

Are There Any Known Photographs of Blitzen During Its Peak Years?

You won’t find many Blitzen photographs from its heyday, as historical documentation from the late 1800s to early 1900s is extremely scarce. Most known images show only the later deteriorating structures.

What Was the Highest Recorded Population of Blitzen?

You won’t find exact peak population records for this ghost town, but historical documents indicate it was small, with just three families remaining by 1924 before its population decline led to abandonment.

Were There Any Notable Crimes or Lawlessness in Blitzen’s History?

Despite operating for 28 years without a single reported crime at its post office, you won’t find records of any significant criminal activities in Blitzen. Local law enforcement wasn’t needed in this peaceful settlement.

Did Any Famous Pioneers or Historical Figures Visit Blitzen?

You won’t find records of any famous visitors or pioneer stories tied directly to Blitzen. While ranchers like Peter French influenced the broader valley region, no notable historical figures are documented visiting the town.

What Native American Artifacts Have Been Found at the Blitzen Site?

You’ll find stone tools, projectile points, and fire pit remains near Blitzen that match Native artifacts discovered at nearby Catlow Cave, demonstrating the area’s cultural significance to indigenous peoples over millennia.

References

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Blitzen

- https://traveloregon.com/things-to-do/culture-history/ghost-towns/blitzen/

- https://www.oregonencyclopedia.org/articles/catlow_valley/

- https://kids.kiddle.co/Blitzen

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_ghost_towns_in_Oregon

- https://www.ghosttowns.com/states/or/blitzen.html

- https://theroaringspringsranch.com/history

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/P_Ranch

- https://www.oregonencyclopedia.org/articles/donner-und-blitzen-river/

- https://www.oregonhistoryproject.org/narratives/high-desert-history-southeastern-oregon/resettlement/a-hard-country-to-settle/