You’ll find Brashville near the Missouri River and Bon Homme Island, where it was established in 1858. This small prairie settlement faced early challenges, including eviction by federal troops before legal settlement began in 1859. While the community thrived on agriculture and strong neighborly bonds, unfulfilled railroad promises led to its isolation and decline. Today, weathered buildings and abandoned structures tell a compelling story of pioneer dreams and prairie resilience.

Key Takeaways

- Brashville was established in 1858 near the Missouri River but faced early setbacks with federal troop evictions under the Treaty of Washington.

- Failed railroad promises and economic isolation led to Brashville’s decline, as neighboring towns benefited from rail access while it remained disconnected.

- The town’s population declined as agricultural challenges and lack of transportation infrastructure forced younger generations to seek opportunities elsewhere.

- Abandoned structures, including old processing areas and the post office, now stand in severe disrepair with no formal preservation programs.

- Community life centered around the general store, Methodist church gatherings, and seasonal celebrations before the town’s eventual abandonment.

The Birth of a Prairie Settlement

While the Dakota Territory remained largely unsettled in the 1850s, pioneers first attempted to establish Brashville in 1858 near the Missouri River and Bon Homme Island in present-day Bon Homme County.

These early settler challenges proved formidable as federal troops from Fort Randall enforced the Treaty of Washington, evicting the pioneers and destroying their cabins to protect Yankton Sioux rights.

You’ll find the true birth of Brashville occurred in 1859 when legal settlement finally began near Bon Homme Village on the mainland shore.

The community dynamics were shaped by the region’s rich resources and strategic location. The area’s early development was influenced by a French fur trader whose good reputation led to the county’s name. The Dakota Land Company established several early settlements in the territory, including trading posts that became vital economic hubs.

The abundant natural wealth and prime positioning along key routes defined how Brashville’s early residents lived, worked and prospered together.

As railroads arrived in 1872, they transformed Brashville’s accessibility, bringing waves of European immigrants seeking economic opportunities and the promise of free land under the Homestead Act.

Early Pioneer Life in Brashville

Although settlers flocked to Brashville with dreams of prosperity in the 1870s, they’d soon face the stark realities of prairie life.

Pioneer hardships hit hard as you’d struggle to build basic shelter, often starting with crude claim shanties lacking floors or roofs. You’d endure howling prairie wolves and brutal weather while working to establish your 160-acre claim. Colorado grasshoppers devastated crops for years, making survival even more challenging. The Sioux population remained a significant presence in the region, maintaining their traditional territories.

Community resilience emerged as your lifeline. You’d find bachelor neighbors willing to help construct dwellings, and your family would gradually expand living spaces as prosperity allowed.

Churches formed quickly, giving you essential social connections while preserving your cultural heritage. You’d plant trees to gain additional acreage and establish self-sufficiency, all while dealing with isolation before railroad access in 1881 finally connected you to distant markets.

Railroad Dreams and Broken Promises

You’d find the story of Brashville’s railroad aspirations marked by unfulfilled promises, as the town’s hopes of becoming a bustling transport hub never materialized when planned rail lines bypassed the settlement.

Your examination of historical records would reveal how town leaders actively courted railroad companies through the 1880s, investing considerable resources in preparation for tracks that never arrived. Similar to local speculators who invested heavily in anticipated rail routes, Brashville’s citizens purchased land near proposed track locations. While other towns benefited from the standard gauge railroad reaching the Black Hills in 1885, Brashville remained disconnected from this vital transportation network.

The community’s missed opportunity for rail connectivity ultimately contributed to its economic decline, as neighboring towns with railroad access flourished while Brashville’s isolation deepened.

Failed Transport Hub Dreams

Since railroad speculation drove much of South Dakota’s early development, Brashville’s founders pinned their hopes on becoming a major transport hub in the late 1880s.

During this period, communities across the state saw 285 new towns established as railroad companies aggressively expanded their networks.

You’ll find their pioneer challenges reflected in the aggressive settlement strategies they employed, including land deals and petitions to attract railroad interest.

But you’d have seen their dreams crumble as railroad companies chose alternative routes, prioritizing their corporate interests over community needs.

Like many Black Hills settlements, Brashville watched helplessly as rail lines bypassed their town, despite earlier promises of connectivity. Following the Fremont, Elkhorn and Missouri Valley railroad’s completion to Buffalo Gap in 1885, hopes for a connection to Brashville dimmed further.

The expected economic boom never materialized, and without reliable transport for goods and passengers, the community’s isolation deepened.

What started as an ambitious vision of a bustling railroad center gradually faded into another prairie ghost town.

Tracks That Never Came

When railroad companies began surveying routes through South Dakota in the 1880s, Brashville’s residents watched enthusiastically as surveyors mapped potential lines near their settlement.

Railroad negotiations between companies and neighboring towns left Brashville stranded, as routes diverted toward more promising economic hubs. The resulting economic isolation crippled the town’s growth potential.

- Speculators and landowners influenced route changes that bypassed Brashville

- Railroad firms made empty promises that generated false hope among residents

- Narrow gauge mining routes and standard gauge lines chose other corridors

- Mail delivery, goods transport, and passenger travel remained limited

- Neighboring communities with rail access, like Parkston, thrived while Brashville declined

You’ll find this pattern repeated across the Black Hills region, where communities without rail connections often faded into ghost towns.

Lost Economic Opportunities

The promise of railroad prosperity slipped through Brashville’s fingers as the town watched neighboring communities reap the economic rewards of rail connections during the Great Dakota Boom.

You can still see the stark contrast between what could have been and what became reality. While rail-connected towns flourished with lumber shipments, mail service, and agricultural trade opportunities, Brashville experienced significant economic shifts that stunted its growth.

Without rail access, the town couldn’t compete with communities that had direct lines to markets and supplies. Despite community resilience and attempts to adapt, the lack of railroad infrastructure proved devastating.

The abandoned dreams of rail connection left Brashville unable to participate in the region’s most transformative period of economic development from 1878 to 1887.

Daily Life in a Small Plains Town

Life in Brashville centered around tight-knit community bonds that were typical of small Plains towns in South Dakota. You’d find neighbors helping neighbors, sharing resources and traditions that defined the spirit of Plains living. Like many other communities that became ghost towns, Brashville’s close social fabric eventually unraveled as economic changes took their toll. Similar to nearby Ardmore and Okaton, the population steadily declined as agriculture transformed and opportunities diminished.

Community gatherings brought folks together regularly, strengthening the connections that helped everyone survive the harsh Dakota conditions.

- Local general store served as the heart of daily commerce and social interaction

- Weekly potluck suppers at the Methodist church united families across generations

- Seasonal barn dances and harvest festivals celebrated local traditions

- Children walked together to the one-room schoolhouse on Main Street

- Farmers gathered at dawn at Joe’s Café to discuss crops and weather

These simple yet meaningful routines created a self-reliant community where everyone played a crucial role in maintaining the town’s social fabric.

Agricultural Heritage and Local Economy

Building Brashville’s economic foundation, agricultural innovation played a central role in shaping the town’s destiny throughout the late 1800s and early 1900s.

You’d find local farmers embracing diversified farming strategies and implementing irrigation systems to combat the region’s harsh climate. During the Great Dakota Boom of 1878-1887, agricultural growth surged, though droughts tested local resilience.

Innovative Dakota farmers adapted to nature’s challenges, diversifying crops and modernizing irrigation while weathering boom-and-bust cycles of the 1880s.

As mechanization transformed farming practices, Brashville’s agricultural community adapted by managing larger acreages and exploring new markets.

The New Deal’s agricultural subsidies provided essential support during tough times, helping families maintain their farms through generations. Many of these became Century Farms, symbols of enduring commitment to the land.

These family-owned operations didn’t just preserve agricultural heritage – they strengthened community bonds and sustained rural traditions.

The Slow Fade: Why Brashville Disappeared

As you explore Brashville’s decline, you’ll find its story mirrors countless small prairie towns that banked their futures on promised railroad connections that never materialized.

The town’s initial agricultural promise couldn’t sustain itself without reliable transportation links to larger markets, leaving farmers increasingly isolated from essential trade routes.

What began as a hopeful farming community in the early 1900s steadily lost its population as younger generations sought opportunities in more connected areas, leaving behind weathered buildings as evidence to Brashville’s unfulfilled railroad dreams.

Failed Railroad Dreams

While many South Dakota towns thrived with the arrival of the railroad in the late 19th century, Brashville’s fate took a different turn when railroad companies bypassed the settlement in favor of more strategically located communities.

The railroad politics of the era meant that towns lived or died by their rail connections, and settlement strategies often involved relocating entire communities just to secure a coveted rail stop. Without rail access, Brashville’s economy withered as neighboring towns became bustling hubs of commerce and connectivity.

- You couldn’t ship grain or receive construction materials efficiently

- Local businesses struggled to compete with rail-connected towns

- Mail and newspaper delivery remained slow and unreliable

- The community missed out on crucial railway-based social connections

- Investments and development opportunities went to other towns

Agricultural Promise Unfulfilled

Despite initial hopes for agricultural prosperity, Brashville’s farming community faced devastating setbacks from the region’s unforgiving climate and inadequate infrastructure.

You’d have seen settlers struggle against harsh Dakota weather patterns, with cycles of drought crushing their dreams of bountiful harvests. Without railroads or grain elevators nearby, farmers couldn’t effectively market what crops did survive.

Agricultural innovations from local experiment stations, like drought-resistant grasses, came too late for most. The settlement challenges proved insurmountable – homestead plots were too small for sustainable farming, and settlers lacked capital for necessary improvements.

Traditional Midwestern farming methods failed in Dakota’s unforgiving soil, while limited access to credit prevented investments in irrigation.

Sadly, you’d have watched as families abandoned their farms one by one, their hopes of agricultural success withering like their crops in the harsh Dakota sun.

What Remains Today

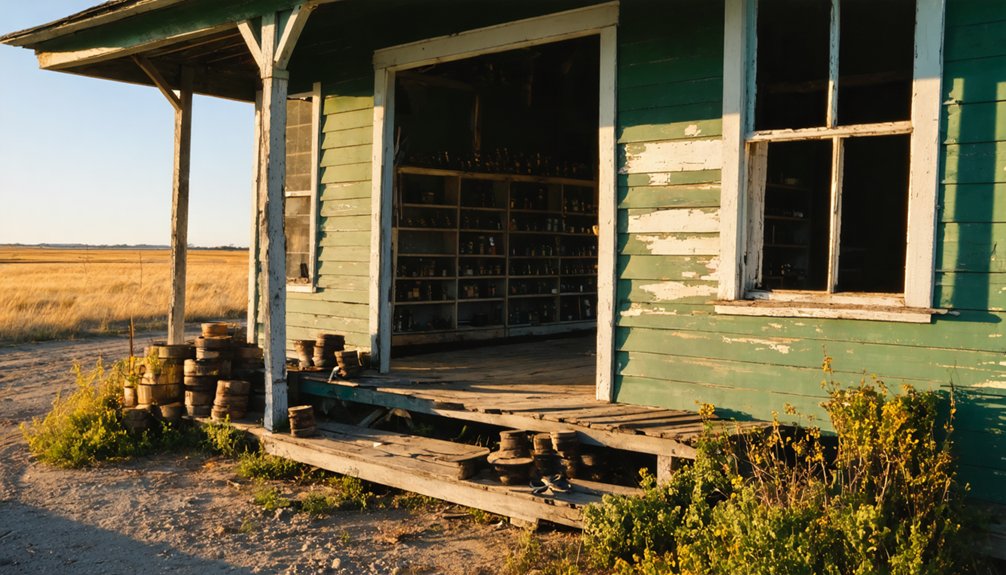

The abandoned structures of Brashville tell a stark tale of decline, with most buildings either collapsed or in severe disrepair.

Today, you’ll find a ghost town that’s reverted largely to its natural state, where the South Dakota landscape has reclaimed much of what once stood.

While you can still explore the site freely on foot, there’s no formal tourism infrastructure or interpretive displays to guide your visit.

- Deteriorating building remnants stand as silent witnesses to the town’s past

- Empty foundations and scattered rubble mark where structures once stood

- Natural grasslands and open fields have overtaken former developed areas

- No permanent residents remain, though occasional visitors pass through

- Previous preservation attempts, including a ghost town museum project, have ceased to operate

Notable Landmarks and Structures

Standing as remnants of a once-bustling Black Hills mining community, Brashville’s notable landmarks showcase the town’s brief but significant history through scattered foundations and weathered structures.

You’ll find mining infrastructure throughout the site, including old processing areas with bolt fixtures where machinery once stood. The post office, one of the first established community landmarks in the Black Hills district, served as a crucial communication hub.

Wooden structures that once housed shops, saloons, and general stores have left behind stone foundations and metal fixtures along what was the main street. While specific documentation is limited, evidence suggests there was also a chapel, typical of Black Hills mining settlements, along with community halls where residents gathered for social events.

Historical Impact on Brown County

While Brashville’s rise and fall mirrored broader settlement patterns in Brown County, its unique position in the region’s development becomes apparent through the county’s earliest roots in 1877. The settler stories of pioneers like Clarence D. Johnson, who staked their claims along the James River, set the stage for dramatic economic shifts that would shape the county’s future.

You’ll find that railroad access became the determining factor in which communities survived and which became ghost towns.

- Communities that secured rail connections thrived, while others, like Brashville, faced decline

- Early settlers followed military and government trails, establishing claims in previously uninhabited prairie

- Agricultural prosperity drove population growth until the devastating drought of 1926

- Ethnic diversity, including Norwegian, Swedish, Finnish, and Welsh settlers, enriched local culture

- Railroad-connected towns attracted businesses, while others struggled to maintain economic viability

Legacy Among South Dakota Ghost Towns

While you’ll find many mining ghost towns throughout South Dakota’s Black Hills region, Brashville stands out as one of the state’s rare agricultural ghost towns that struggled until the mid-1900s.

Today, you can explore the remaining foundations and scattered artifacts that tell the story of this farming community’s final years, though most structures haven’t survived.

The site has received recognition from the Brown County Historical Society, which maintains records of Brashville’s significance in demonstrating the challenges faced by early agricultural settlements in the region.

Agricultural Town’s Final Stand

Although many South Dakota ghost towns arose from abandoned mining operations, Brashville’s legacy stands apart as a quintessential example of an agricultural community’s decline.

You’ll find its story deeply woven into the fabric of rural America’s cultural heritage, where community resilience faced mounting challenges from changing economic forces and environmental pressures.

- Railroad rerouting severed crucial transportation arteries that once carried grain and livestock to market

- Young residents steadily departed for urban opportunities, leaving an aging population behind

- Local businesses and services gradually shuttered as the agricultural workforce shrank

- Environmental challenges like drought and soil depletion struck devastating blows to farm productivity

- The town’s single-sector economy couldn’t adapt to modernization and mechanized farming methods

Historical Preservation Status Today

Despite its historical significance as an agricultural settlement, Brashville’s physical remnants and preservation status pale in comparison to South Dakota’s better-documented ghost towns.

You’ll find no protective designations or formal preservation programs safeguarding the site’s heritage, unlike other Black Hills ghost towns that maintain visible ruins and historical markers.

The preservation challenges are substantial – weather damage, vandalism, and neglect continue to erase what’s left of Brashville’s structures.

While enthusiastic locals occasionally share oral histories, there’s limited archival documentation of the town’s past.

Community awareness remains low, with no organized tourism infrastructure or educational resources at the site.

Among South Dakota’s 600-plus ghost towns, Brashville stands as one of the less prominent examples, lacking the mining or railroad heritage that’s helped preserve other abandoned communities.

Frequently Asked Questions

Were There Any Notable Crimes or Murders Reported in Brashville’s History?

Like a spotless slate, you won’t find any documented Brashville crimes or historical murders in the records. The town’s decline came from economic struggles rather than criminal activity.

What Native American Tribes Originally Inhabited the Area Before Brashville’s Establishment?

You’ll find the area was primarily inhabited by Sioux peoples, particularly the Lakota, who maintained their tribal history through spiritual sites and hunting grounds before European-American settlement changed the region’s dynamics.

Did Any Famous People Ever Visit or Stay in Brashville?

You won’t find records of any famous visitors or historical figures staying in Brashville – the town’s modest size, remote location, and working-class roots didn’t attract notable personalities to the area.

What Was the Average Cost of Land in Brashville During Its Peak?

Like a treasure map with missing pieces, you’ll find no definitive records of Brashville’s land prices. Economic factors suggest costs likely matched other small Black Hills mining towns: $5-50 per plot.

Were There Any Documented Paranormal Activities in Brashville’s Abandoned Buildings?

You won’t find documented paranormal investigations or ghost sightings in Brashville’s abandoned structures, as there aren’t any verified records of supernatural activity and most buildings no longer exist.

References

- https://www.sdpb.org/rural-life-and-history/2023-08-21/some-black-hills-ghost-towns-and-their-origins

- https://www.powderhouselodge.com/black-hills-attractions/fun-attractions/ghost-towns-of-western-south-dakota/

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_0WNYsFLSLA

- https://www.sdhspress.com/journal/south-dakota-history-2-2/some-black-hills-ghost-towns-and-their-origins/vol-02-no-2-some-black-hills-ghost-towns-and-their-origins.pdf

- https://www.blackhillsbadlands.com/blog/post/old-west-legends-mines-ghost-towns-route-reimagined/

- https://aberdeenmag.com/2019/01/the-ghost-towns-of-brown-county/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_ghost_towns_in_South_Dakota

- https://icatchshadows.com/okaton-and-cottonwood-a-photographic-visit-to-two-south-dakota-ghost-towns/

- https://openprairie.sdstate.edu/etd/4061/

- https://www.sdpb.org/rural-life-and-history/settlement-stories-bon-homme-county-in-the-moment