Cabernet was once a thriving 19th-century California wine community that collapsed during Prohibition. You’ll find abandoned vineyards, weathered wine cellars, and the remnants of a complex social structure that included European landowners, Chinese laborers, and indigenous workers. The ghost town features architectural ruins set against volcanic soil terroir that once produced award-winning wines. Exploring these forgotten foundations offers a glimpse into the devastating impact economic policies can have on agricultural communities.

Key Takeaways

- Cabernet was a California ghost town with historical significance related to Cabernet Sauvignon wine production before Prohibition.

- The town’s abandoned vineyards and cellars reflect the devastating economic impact of the Volstead Act enacted in 1919.

- Remnants of wine production structures still exist, attracting history enthusiasts and wine aficionados.

- Preservation efforts face challenges from weather damage and wildfire threats, relying primarily on private ownership.

- Visitors should respect historical artifacts, stay on marked paths, and follow “Leave No Trace” principles when exploring.

The Rise and Fall of Cabernet’s Wine Legacy

While Cabernet Sauvignon’s heritage in California traces back to 1852, when French nurseryman Antoine Delmas introduced this noble grape to Santa Clara Valley, its legacy would unfold across multiple regions with varying success.

You can trace Cabernet’s journey from Almaden’s first commercial blends to Morris Estee’s pioneering Napa plantings at Hedgeside estate.

The Cabernet history includes remarkable highs—like Inglenook’s gold medal at the Paris World Fair—followed by devastating lows.

Phylloxera decimated imported Bordeaux vines, and Prohibition (1920-1933) abandoned countless vineyards to wilderness.

Areas like Lodi’s Clements Hills, adjacent to actual mining ghost towns, attempted vineyard revival but couldn’t sustain momentum against economic pressures and changing markets.

James Concannon’s imported Château Margaux clones (07, 08, 11) remain California’s viticultural foundation, a living proof of early ambitions.

The varietal’s meteoric rise to popularity is evidenced by its growth from 247,000 acres in 1990 to over 840,000 acres globally by 2017.

Modern winemaking in Clements Hills has introduced exceptional Cabernet Sauvignon like Peltier Winery’s Schatz Family Reserve, grown on volcanic soil that naturally enhances the wine’s structure and quality.

Uncovering the Town’s Forgotten Vineyards

Despite being reclaimed by nature for decades, Cabernet’s forgotten vineyards tell a rich viticultural history through their weathered remnants. As you explore the area, you’ll discover stone terraces and walls that once supported thriving Cabernet Sauvignon vines planted after the mining boom subsided in the late 1800s.

These historic vineyards possess unique terroir—volcanic soils and mineral deposits that imparted distinctive characteristics to wines produced here. The area’s geological composition resembles the exposed vertical bedding found in prestigious Yountville vineyards. Since the 1980s, researchers have methodically mapped these abandoned sites, preserving California’s grape heritage through the recovery of disease-resistant clones like the rare Cabernet Sauvignon Clone 6 from Jackson Station.

Today’s preservation efforts include replanting with heritage varieties and restoring original structures, allowing you to witness the rebirth of Cabernet’s viticultural legacy through limited-release wines that embody this ghost town’s distinctive history. Many of these vineyards suffered dramatic declines during the Great Depression, similar to the fate of numerous historic California wineries that fell into disrepair.

Daily Life in a 19th Century Wine Community

You’d find stark contrasts between laborers and elites in Cabernet’s wine community, where Native and Chinese workers toiled from dawn to dusk while owners enjoyed leisure activities and formal gatherings.

Daily life revolved around seasonal rhythms, with harvest time requiring all-hands participation but offering rare moments when social hierarchies temporarily relaxed during evening grape crushes. Many Chinese laborers constructed subterranean wine caves that were essential for proper aging and storage of the community’s wine production. Spanish Franciscan missionaries had established the winemaking traditions that guided production methods throughout the region.

Community traditions centered around the winery space itself, where celebrations marked key agricultural milestones, though participation was strictly governed by one’s position in the social order that privileged European immigrants and landowners over indigenous workers.

Work Versus Leisure

In the vineyards of 19th century California wine communities, daily life represented a stark contrast between relentless labor and limited leisure, especially for the marginalized workers who built the industry. Your work life balance would have been virtually nonexistent as a laborer, with seasonal demands dictating every aspect of your existence. The wine industry’s growth after the California Gold Rush in 1848 led to over 100 vineyards in the greater LA area, creating a route known as Vineyard Lane between San Pedro and Los Angeles. Wine production created challenges with bottle costs, causing many producers to simply reuse empty bottles rather than invest in new glass containers.

- Native American workers faced particularly harsh conditions, often paid in alcohol despite being legally prohibited from drinking, leading to cycles of addiction.

- Chinese immigrants formed a significant workforce in Napa Valley but endured racial discrimination and exclusion from citizenship.

- Laborers created informal social networks despite exploitation, gathering for gambling and communal activities during rare off-hours.

- Women gradually challenged male dominance, with pioneers like Josephine Tychson owning and operating vineyards despite significant labor struggles.

Community Gathering Traditions

While California’s earliest wine communities emerged around Spanish missions in the 18th century, these settlements gradually evolved into complex social ecosystems with distinct gathering traditions that reflected the region’s cultural diversity.

You’d witness cultural blending during harvest celebrations, where entire communities participated in grape picking and crushing, followed by feasting, music, and dancing. These communal rituals transcended ethnic boundaries, though laws strictly controlled Indigenous participation.

After mission secularization, gatherings shifted from church-centered events to rancho celebrations and commercial venues like taverns and wineries. European immigrants introduced new traditions—Italian and French feasting customs merged with Mexican fiestas and religious processions. Chinese laborers made significant contributions to these early wine communities until their forced exodus following the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882.

Public spaces became sites of both celebration and tension, as authorities monitored gatherings while diverse populations created shared traditions despite restrictive laws governing their interactions.

The Impact of Prohibition on Cabernet’s Fate

You’ll find California’s wine industry devastated by the Volstead Act of 1919, which triggered the rapid economic collapse of once-thriving Cabernet-producing communities.

Approximately 660 wineries vanished during Prohibition’s 14-year grip, transforming vibrant production centers into abandoned properties with neglected cellars and deteriorating infrastructure.

The ghost town of Winehaven stands as physical testimony to this era, its shuttered buildings and empty wine cellars embodying the catastrophic halt of California’s Cabernet cultivation that would take decades to recover. Similar to Cerro Gordo’s transition from a violent mining town to an abandoned settlement, Cabernet’s decline represents another chapter in California’s ghost town legacy.

Economic Collapse Timeline

The economic collapse of Cabernet began dramatically with the passage of the Volstead Act in 1919, which swiftly devastated California’s once-thriving wine industry. Before Prohibition, you’d find over 700 wineries demonstrating remarkable economic resilience across the state, but by 1933, barely 40 remained operational.

The timeline of destruction unfolded relentlessly:

- 1919-1920: Immediate closure of commercial Cabernet production facilities following Volstead Act implementation

- 1921-1925: Mass abandonment of vineyards as financial losses mounted

- 1926-1929: Widespread community deterioration as wine-dependent economies collapsed

- 1930-1933: Great Depression compounded existing hardships, further hampering vineyard restoration

What had been internationally recognized wineries fell into disrepair, transforming vibrant communities into ghost towns as skilled workers fled and tourism disappeared.

Wine Cellars Abandoned

Shadows of California’s once-thriving wine industry linger in Cabernet’s abandoned wine cellars, where dust-covered barrels and cobwebbed fermentation tanks tell the story of Prohibition’s devastating impact.

You’d hardly recognize these hollow chambers that once housed California’s proud vintages. When the legislation passed, Cabernet’s winemakers watched their numbers plummet from 700 to barely 100 operations statewide.

Production collapsed by 94%, forcing vineyard owners to rip up vines or convert to alternative crops.

Some cellars survived through legal loopholes—producing sacramental wine, grape juice, or dried grape bricks with thinly veiled instructions.

But most facilities deteriorated beyond recognition. The few cellar restoration efforts following Repeal couldn’t recover what was lost: generations of winemaking knowledge vanished alongside the abandoned wine infrastructure, creating a legacy gap that took decades to bridge.

Architectural Remains: What Survives Today

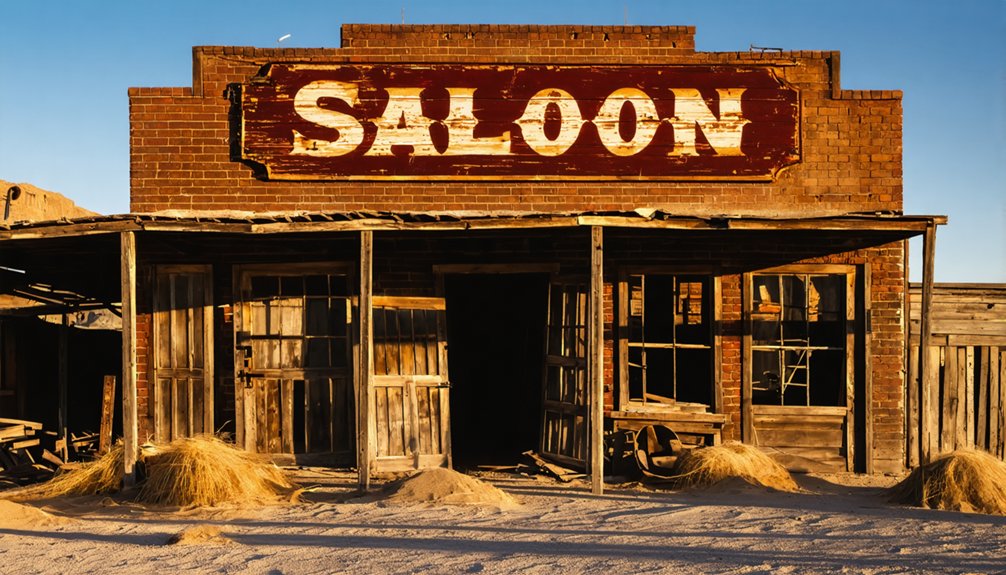

Remnants of Cabernet’s once-thriving community survive today primarily through scattered architectural features, each telling a story of the town’s wine-producing past.

The abandoned structures showcase distinctive architectural styles and historical significance, revealing a complex tapestry of California’s viticultural heritage.

Each weathered beam and crumbling facade tells a story of viticultural ambition, artistry, and ultimate abandonment.

When you visit Cabernet today, you’ll find:

- A brick, castle-like winery overlooking the valley, now fenced off with boarded windows

- Several worker cottages with white exteriors and faded blue trim, remnants of the communal living arrangements

- The former production building with hand-hewn lumber construction using square nails, demonstrating 19th-century craftsmanship

- Foundation outlines of the general store, which once featured wagon wood construction on its lower portion

These deteriorating structures stand as silent witnesses to California’s pioneering wine industry.

Ghostly Encounters Among the Abandoned Cellars

Whispers of the past echo through Cabernet’s abandoned cellars, where visitors have reported numerous supernatural encounters since the winery’s closure during Prohibition.

You’ll hear stories of ghostly sightings, particularly of George C. Yount’s spirit ascending nearby hillsides or shadowy figures with long beards moving through stone archways at Greystone.

The eerie sounds of footsteps and unexplained noises permeate these spaces, amplified by fog that shrouds old buildings and wind whistling through boarded windows.

Many reports connect these phenomena to Prohibition-era activities—former owners and bootleggers who met violent ends are said to manifest as dark presences in rooms where illegal operations once thrived.

These abandoned cellars, standing as silent witnesses to California’s turbulent wine history, continue to attract those seeking connection with spirits from another era.

Comparing Cabernet to Other California Ghost Towns

While Cabernet stands apart in California’s ghost town legacy, its wine-centric origins create a distinctive historical footprint compared to the state’s more numerous mining-related abandoned settlements.

Unlike Bodie or Calico, which rose and fell with gold and silver extraction, Cabernet’s story weaves through agricultural heritage, European wine artisans, and Prohibition-era collapse.

- Mining towns followed predictable boom-bust cycles when resources depleted, while Cabernet’s decline stemmed from economic and regulatory pressures on vintners.

- Cabernet’s cultural heritage features European winemaking traditions rather than the lawless reputation of places like Bodie.

- Mining settlements like Port Wine often housed transient populations, whereas Cabernet built around stable agricultural communities.

- Today’s ghost wineries frequently blend preservation with active production, unlike the purely historical nature of preserved mining towns.

Preservation Efforts and Historical Recognition

Preservation efforts for Cabernet face unique challenges compared to California’s better-known ghost towns, reflecting both its wine-country heritage and the complications of historical recognition in the modern era.

Unlike sites such as Bodie or Cerro Gordo, Cabernet hasn’t benefited from major direct preservation initiatives, leaving its fate largely to private owners or local heritage groups.

While Bodie and Cerro Gordo enjoy formal protection, Cabernet’s history survives largely through passionate locals and private stewardship.

The preservation challenges include high-altitude weather damage, wildfire threats, and limited public funding.

Without official historical landmark designation, Cabernet relies on community involvement through digital engagement and volunteer restoration work.

You’ll find that successful preservation models in surrounding areas combine traditional craftsmanship with modern storytelling techniques, creating virtual experiences that offset limited physical access.

These digital preservation efforts serve dual purposes—documenting history while generating interest that might translate to financial support for ongoing conservation work.

Planning Your Visit to Cabernet’s Historic Ruins

Journeying to Cabernet’s historic ruins requires careful planning and a spirit of adventure, as this remote Sierra County ghost town offers little in the way of modern amenities or tourist infrastructure.

Located near La Porte in northern California’s Sierra Nevada mountains, this former Gold Rush settlement demands self-reliance and proper navigation tools for successful exploration.

Essential exploration tips for your visit:

- Bring robust navigation equipment—GPS devices, topographic maps, and compass—as cell service is unreliable in this isolated terrain

- Pack ample water, food, and emergency supplies; no services exist at the site

- Visit during favorable weather conditions (late spring through early fall) to avoid dangerous winter conditions

- Respect potential private property boundaries and practice “Leave No Trace” principles while examining remaining foundations and artifacts

Frequently Asked Questions

Did Indigenous Peoples Inhabit the Cabernet Area Before the Winery Settlement?

Yes, you’ll find indigenous cultures did inhabit the area before winery settlements. Archaeological evidence confirms Wappo and Patwin tribes maintained communities there for thousands of years, stewarding these lands through established cultural practices.

What Caused the Devastating Fire of 1897 Mentioned in Local Records?

You’ll find historical accounts don’t definitively establish the fire’s cause. Possible origins include mining accidents, stray gunfire igniting structures, or arson—all fitting the violent atmosphere of Cerro Gordo’s mining era.

Were Any Famous Wines Produced in Cabernet Before Abandonment?

No, you won’t find famous wineries or historical vintages from Cabernet as it wasn’t a real California ghost town with documented wine production before any purported abandonment.

Did Cabernet Ever Attempt to Revitalize After Prohibition Ended?

No documented revitalization efforts exist for Cabernet ghost town after Prohibition ended. You’ll find post-prohibition challenges primarily affected established wine regions rather than abandoned mining communities like Cabernet.

Are There Restrictions on Metal Detecting or Artifact Collection?

You must adhere to metal detecting regulations when exploring. Public lands prohibit removal of artifacts over 100 years old, while private lands require owner permission. Artifact preservation policies protect historical significance of sites.

References

- http://www.hopesendwine.com/bodie-california/

- https://www.sfgate.com/travel/editorspicks/article/california-ghost-town-tiktok-underwood-cerro-gordo-15970036.php

- https://thevelvetrocket.com/2010/07/13/california-ghost-towns-port-wine/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_ghost_towns_in_California

- http://joysjoyofwine.blogspot.com/2013/09/a-haunting-look-back-at-ghost-wineries.html

- https://www.youtube.com/shorts/XCt-KHiiGU0

- https://www.visitmammoth.com/blogs/history-and-geology-bodie-ghost-town/

- https://capstonecalifornia.com/study-guides/varieties/red/cabernet_sauvignon/history

- https://www.lodiwine.com/blog/Peltier-Winery-finds-a-natural-sweet-spot-in-Lodi-s-Clements-Hills-to-produce-its-new-Reserve-Cabernet-Sauvignon

- https://www.thewinecellarinsider.com/california-wine/california-wine-history-from-early-plantings-in-1800s-to-today/