Fountain Springs, a California ghost town, served as a vital Butterfield Overland Mail station from 1858-1861. You’ll find it strategically positioned 14 miles southeast of Tule River Station, where it once facilitated Gold Rush travelers and miners. Today, you can explore scattered ruins, crumbling foundations, and the historic Old Stage Saloon (est. 1858) by following California Historical Landmark No. 648 south of Porterville. The site’s unprotected artifacts reveal untold stories of stagecoach passengers and station keepers.

Key Takeaways

- Fountain Springs was a vital Butterfield Overland Mail station established before 1855 at a strategic California crossroads.

- The site served as a crucial Gold Rush transit hub, connecting miners to camps while avoiding difficult terrain.

- Daily life centered around stagecoach operations, with station keepers managing horse changes, accommodations, and mail security.

- Only scattered ruins remain today, including deteriorated hotel foundations and stone fireplaces across the arid landscape.

- Visitors can find the unpreserved ghost town marked by California Historical Landmark No. 648 near Porterville.

The Rise of a Butterfield Overland Mail Station

As the mid-19th century brought waves of prospectors and pioneers westward, Fountain Springs emerged as a significant waypoint established before 1855 at a strategic crossroads. Positioned at the junction of the Stockton-Los Angeles Road and the path to Kern River gold mines, this settlement quickly became indispensable to California’s developing infrastructure.

From 1858 to 1861, Fountain Springs transformed into an essential component of Butterfield operations, serving as a station along the federally authorized mail route. Located 14 miles southeast of Tule River Station and 12 miles north of Mountain House, it facilitated necessary mail logistics—changing horses, delivering correspondence, and providing weary travelers with meals and rest. This historical site should not be confused with other locations sharing the same place name across different geographical regions. The station was part of the larger network that included Elkhorn Spring Station, which was positioned 22 miles east of Fresno City along the First Division route.

The station’s proximity to a reliable water source proved invaluable, supporting both domestic needs and gardens while connecting remote mining communities to the wider commercial networks of a young California.

Strategic Location at California Crossroads

At the junction of the Stockton–Los Angeles Road and the path to Kern River gold mines, you’ll find Fountain Springs’ strategic value as a 19th-century crossroads.

You’re examining a location that facilitated critical north-south travel through California while simultaneously connecting gold seekers to mining districts.

Your understanding of this settlement must acknowledge how its position at converging transportation routes transformed a simple waypoint into an essential hub for travelers, commerce, and communication during California’s formative development. The site later became an important station on the Butterfield Overland Mail route from 1858 to 1861, further cementing its historical significance. Originally established before 1855, the settlement was located approximately 1-1/2 miles northwest of its current documented position.

Junction of Vital Routes

Situated at the convergence of the Stockton-Los Angeles Road and the route to the Kern River gold mines, Fountain Springs emerged as a critical transportation nexus before 1855.

You’ll find this historic junction 1.5 miles northwest of California Historical Landmark No. 648, at the crossroads that once connected northern and southern California’s transportation networks.

This strategic position elevated Fountain Springs to a Butterfield Overland Mail station from 1858 to 1861, positioned 14 miles southeast of Tule River Station and 12 miles north of Mountain House.

The historical significance of this junction can’t be overstated—it facilitated the movement of gold seekers, mail carriers, and commercial goods across California’s expanding frontier, directly influencing settlement patterns and economic development throughout Tulare County and beyond.

Similar to The Crossings in Fountain Valley, this area likely required zoning changes to accommodate its evolving functions as transportation needs developed.

With its proximity to major routes, Fountain Springs mirrors contemporary transportation hubs like Citadel Outlets, which is strategically located off the I-5 freeway just minutes from Downtown Los Angeles.

Gold Rush Transit Hub

Three essential geographical advantages positioned Fountain Springs as a pivotal Gold Rush transit hub beginning in the early 1850s.

First, its strategic location at the convergence of the Stockton-Los Angeles Road and routes to the Kern River gold fields created a natural gateway for miners.

Second, its reliable water source served travelers traversing between major supply centers and remote mining camps.

Third, its positioning helped avoid Tulare Lake marshlands while facilitating seasonal river crossings.

The settlement’s historical significance expanded when it became a Butterfield Overland Mail station in 1858, cementing its status beyond gold mining operations.

You’d find it supporting nearby camps like Tailholt and Dog Town, channeling prospectors southward as northern strikes waned.

This connectivity transformed a simple spring into a critical node in California’s gold economy.

Like Tailholt, which saw over one million dollars in gold mined from the surrounding area, Fountain Springs benefited economically from the regional mineral wealth.

Similar to Tailholt, which was officially recognized as California Historical Landmark No. 413, Fountain Springs played an important role in California’s gold rush history.

Daily Life at a 19th Century Stagecoach Stop

You’d witness a carefully choreographed routine at Fountain Springs Stagecoach Stop, with station keepers rising before dawn to prepare for arriving coaches while coordinating horse changes and maintaining security.

The accommodations you’d encounter ranged from cramped sleeping quarters with straw mattresses to communal dining areas where simple but hearty meals of beans, bread, and occasional meat sustained weary travelers. Drivers like Charley Parkhurst were instructed to prioritize passenger safety over resisting bandits during potential robberies. The fare for traveling on a stagecoach was quite expensive at $16 one-way in 1872, but provided vital connections between isolated communities.

Your brief respite at this remote outpost would include access to basic provisions like water barrels, pantry goods, and perhaps the luxury of a washbasin—essential comforts in the harsh terrain between Stockton and Los Angeles.

Routine Passenger Experiences

While modern travelers might complain about flight delays or cramped economy seats, passengers aboard nineteenth-century stagecoaches endured far more grueling conditions as a matter of routine.

You’d find yourself pressed knee-to-knee with strangers on leather benches, traveling continuously for up to 25 days with no proper sleep except what you could manage while swaying and bouncing along rough terrain.

The passenger discomfort was relentless—choking dust in summer, bitter cold in winter, and meager, unappetizing food at stations where horses were quickly changed.

Yet travel camaraderie emerged from this shared ordeal, as diverse travelers exchanged stories facing one another in close quarters.

Your luggage sat on your lap while mail pouches crowded your feet, and the coach never stopped long enough for true rest.

Station Keeper’s Responsibilities

Responsibility defined the stationkeeper’s existence in a relentless cycle of duties critical to the stagecoach line’s operation.

You’d find yourself constantly rotating between station upkeep and horse management – ensuring buildings remained safe, wells provided clean water, and grounds stayed clear of hazards.

Horse management consumed much of your day as fresh teams needed preparation every 10-15 miles. You’d oversee feeding, watering, and rotating horses to prevent exhaustion, while keeping extras ready for emergencies.

Beyond physical labor, you’d manage staff payroll, assign duties to hostlers and blacksmiths, and monitor their performance.

Mail and cargo handling required meticulous logging and secure storage. Security remained paramount – you’d implement fire prevention measures, maintain weapons for protection, and establish communication protocols with neighboring stations.

This unforgiving position demanded vigilance in America’s expanding frontier.

Accommodations and Provisions

Life at nineteenth-century stagecoach stops reflected a hierarchy of comfort based on station significance along the route. At Fountain Springs, accommodation types ranged from basic relay shelters to more substantial quarters at junction hotels.

You’d find communal sleeping arrangements with shared rooms and minimal privacy, unless willing to pay premium rates for private chambers.

Food provisions prioritized sustenance over variety, with hearty meals timed to stagecoach schedules. Your dining experience would be communal, fostering connections with fellow travelers while fueling up for the journey ahead.

Your daily existence at these stops included:

- Brief respites at relay stations for horse changes and quick refreshment

- Limited hygiene facilities with rudimentary washrooms and shared toilets

- Evening socialization in common areas before retiring to simple, functional sleeping quarters

Fountain Springs’ Role in the Gold Rush Era

During the height of California’s gold fever, Fountain Springs emerged as a pivotal waypoint in the complex network of Gold Rush settlements that stretched across the state’s rapidly developing frontier.

Positioned strategically at the junction of the Stockton-Los Angeles Road and routes to the Kern River gold mines, it channeled prospectors southward as northern deposits waned.

At this critical crossroads, Fountain Springs directed the migration of gold-seekers toward southern opportunities as northern claims diminished.

You’ll find evidence of economic fluctuations throughout the settlement’s history, with population ebbing and flowing as mining fortunes shifted.

While never achieving the prominence of larger boom towns, Fountain Springs served dual purposes—supporting various mining techniques in nearby operations and facilitating the Butterfield Overland Mail route from 1858 to 1861.

This dual function made the settlement indispensable to the region’s gold economy and communication infrastructure.

What Remains Today: Tracing the Ghost Town

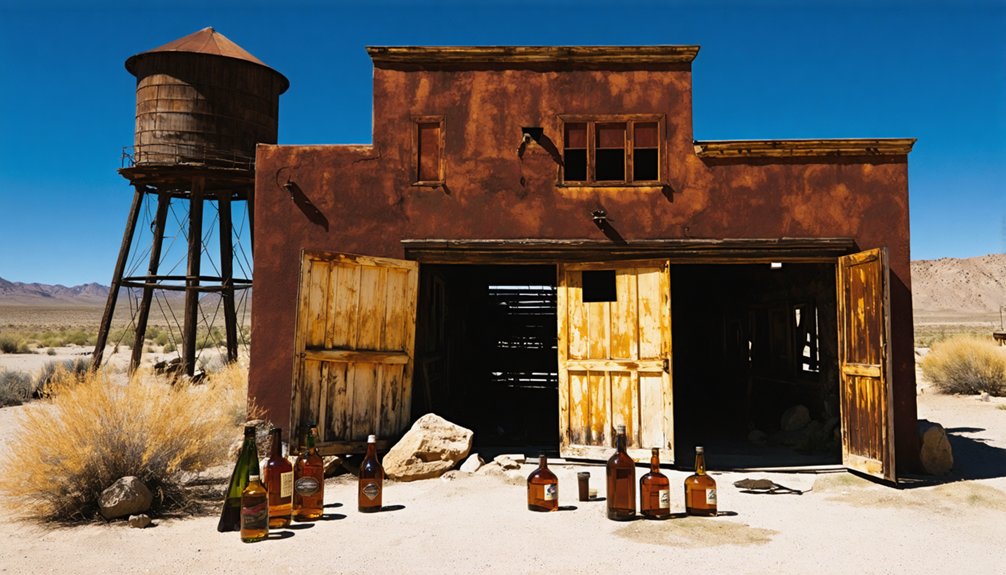

Visitors to Fountain Springs today will find a stark contrast to its gold rush heyday, with the once-bustling settlement now reduced to scattered ruins across the arid landscape.

Your ruins exploration will reveal deteriorated hotel foundations, crumbling stone fireplaces, and remnants of the original store, all slowly surrendering to erosion and invasive vegetation.

For dedicated artifact discovery enthusiasts, the site offers:

- Scattered glass bottles, ceramic shards, and rusting mining equipment

- Exposed foundations revealed by seasonal erosion patterns

- Personal relics like coins and buttons hidden among the overgrown scrub

The site remains unprotected with no official preservation efforts, accessible only via rough unpaved roads.

A solitary roadside marker provides the only official acknowledgment of this forgotten chapter in California’s mining history.

Comparing Fountain Springs to Other California Ghost Towns

While Fountain Springs shares California’s gold-rush ghost town heritage, its distinctive role as a transportation hub sets it apart from the state’s more famous abandoned settlements.

Unlike Bodie, Shasta, or Calico—whose fortunes rose and fell with mining booms—Fountain Springs existed primarily as a crucial junction serving broader regional traffic flows.

The comparison dynamics reveal fundamentally different ghost town evolution patterns. Most abandoned towns depended on a single industry (typically mining) or railroad connections, ultimately collapsing when resources depleted or transportation shifted.

Fountain Springs, however, functioned more like a modern highway rest stop at the intersection of major routes. When the Butterfield Overland Mail ended in 1861 and stagecoach travel declined, the settlement gradually lost its purpose, leaving behind no structures—only the memory of a crucial crossroads in California’s developmental history.

How to Visit and Find Historical Markers

Reaching Fountain Springs today requires careful navigation through Tulare County‘s rural landscape, where the ghost town’s physical remnants have largely disappeared into California’s rolling grasslands.

Time has erased Fountain Springs, leaving only whispers in Tulare County’s undulating grasslands.

The historical significance centers around California Historical Landmark No. 648, situated at the southwest corner of County Roads J22 and M109.

For an ideal visitor experience, follow these directions:

- Drive south from Porterville on Highway 65 to Ducor, then take Avenue 56 (J22) east to reach the intersection with Old Stage Road.

- Look for the historical marker at the J22/M109 junction, coordinates 35°53′28″N 118°54′56″W.

- Visit the Old Stage Saloon (est. 1858), the area’s most notable surviving structure from the Butterfield Overland Mail era.

Bring supplies—the area offers no facilities or services beyond the occasionally operating saloon.

Preserving the Legacy of Fountain Springs

How does a community safeguard the whispers of its past when physical structures have largely vanished? For Fountain Springs, preservation occurs through multiple channels. The site’s designation as California Historical Landmark No. 648 establishes its historical significance within the state’s heritage framework, while markers erected by agencies like the California State Park Commission physically anchor its memory.

Community initiatives play an essential role in this preservation ecosystem. Local historical societies document the settlement’s role as a Butterfield Overland Mail station, while volunteer programs engage residents in protecting remaining ruins near the Springville Stage Route intersection.

Archaeological assessments guide conservation efforts, while interpretive panels contextualize Fountain Springs’ importance during California’s gold rush era. Through these collective actions, the legacy of this pioneer settlement endures despite its ghost town status.

Frequently Asked Questions

Were Any Notable Historical Figures Documented Passing Through Fountain Springs?

You’d love to hear about famous historical travelers gracing your ghost town, wouldn’t you? No notable residents or documented historical figures passed through Fountain Springs, despite its position on the Butterfield Overland Mail route.

What Natural Disasters or Events Contributed to Fountain Springs’ Abandonment?

You won’t find evidence that drought effects or earthquake risks triggered Fountain Springs’ abandonment. Historical records suggest economic factors and transportation route changes—not natural disasters—gradually diminished the settlement’s viability instead.

Did Fountain Springs Have Any Indigenous Population Before European Settlement?

Yes, Yokuts people, particularly Tule River Yokuts tribes, inhabited the Fountain Springs area. You’ll find their cultural heritage reflected in archaeological evidence showing villages established along waterways before European settlers disrupted their autonomous communities.

Were There Any Notable Crimes or Lawlessness Reported at Fountain Springs?

No. You won’t find evidence of notable crimes or lawlessness at Fountain Springs. Historical crime investigation reveals no records, and the absence of law enforcement suggests minimal criminal activity at this small waystation.

Did Fountain Springs Appear in Any Literature or Artistic Works?

You won’t find any literary references or artistic depictions of Fountain Springs in your research. Coincidentally, its brief existence as a mail station wasn’t significant enough to inspire creative works like other ghost towns have.

References

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bz6XtozCSMg

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_ghost_towns_in_California

- https://www.visitcalifornia.com/road-trips/ghost-towns/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fountain_Springs

- https://www.tularecountytreasures.org/tailholt.html

- https://www.islands.com/1684301/californias-zzyzx-exit-mysterious-road-leads-ghost-town-strange-history/

- https://www.hmdb.org/m.asp?m=51865

- https://www.pashnit.com/ca-hot-springs-rd

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Butterfield_Overland_Mail_in_California

- https://www.californiahistoricallandmarks.com/landmarks/chl-648