Canelo, Arizona is a ghost town established in 1882 by Captain Joe Parks along Turkey Creek. You’ll find remnants of its past in the Canelo Schoolhouse (built 1912) and Ranger Station (1932), both listed on the National Register of Historic Places. The small community once thrived with a post office, country store, and the Black Oak Cemetery where 260+ pioneers rest. These preserved structures tell a forgotten frontier tale that awaits your discovery.

Key Takeaways

- Founded in 1882 by Captain Joe Parks, Canelo evolved from a small settlement into a community with ranching and mining activities.

- The Canelo Schoolhouse, built in 1912 and listed on the National Register of Historic Places, served as an educational and social hub until 1948.

- Canelo Ranger Station, constructed in 1932, exemplifies Southwestern architectural style with adobe construction and remains historically significant.

- Black Oak Cemetery contains over 260 documented graves of ranchers, miners, and homesteaders, reflecting the area’s frontier heritage.

- Preservation efforts by organizations like HistoriCorps and The Nature Conservancy maintain Canelo’s historical structures and natural environment for visitors.

The Birth of Canelo: First Settlers and Founding Stories

Nestled between the rolling Canelo Hills and the majestic northern Huachuca Mountains lies the story of a forgotten Arizona settlement.

You’ll find Canelo’s history began in 1882 when Captain Joe Parks established the first homestead along Turkey Creek at nearly 5,000 feet elevation. This brave pioneer marked the beginning of permanent settlement in this remote region.

The town’s name evolved from “Canille” to “Canela” before becoming “Canelo”—Spanish for “cinnamon”—named by Robert A. Rodgers after the brownish-hued nearby hills.

Rodgers, alongside his wife Addie, shaped early community life as postmasters and Forest Rangers. The pioneer lifestyle flourished despite isolation, with early settlers embracing ranching and mining to survive the challenging landscape that would forever define Canelo’s character. By 1904, the settlement had grown enough to establish a post office serving the surrounding homesteaders. Unlike the Canelo tree which is sacred to Mapuche people in South America, Arizona’s Canelo had no known indigenous ceremonial significance.

Life in Early Canelo: Post Office, Store, and Pioneer Infrastructure

While Canelo’s early settlers established their homesteads across the rolling hills, they quickly recognized the need for practical infrastructure to sustain their remote community.

In 1904, the Canelo post office opened under Robert A. Rodgers, who doubled as Forest Ranger, providing crucial postal services until 1924.

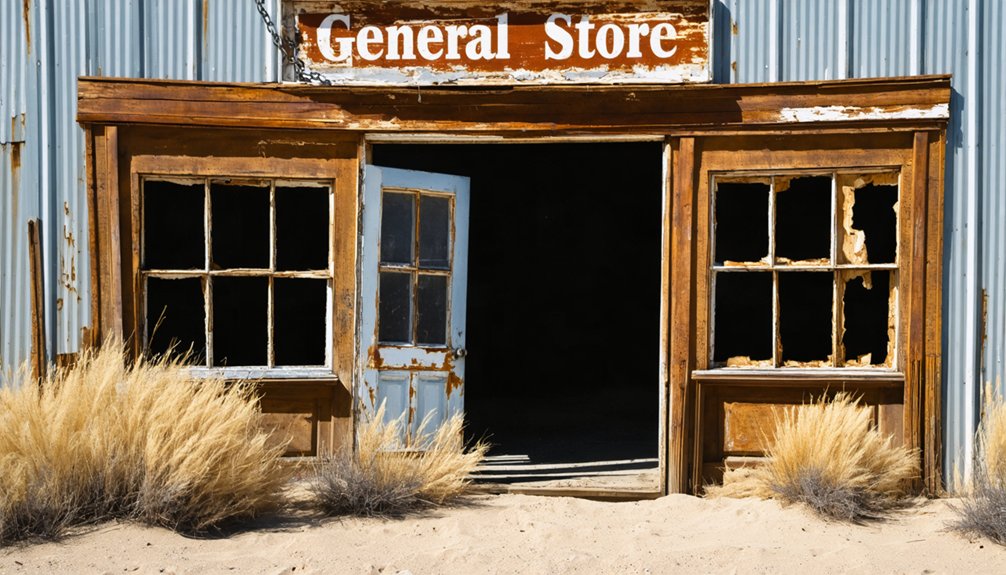

The small country store became Canelo’s beating heart—a place where you’d find essential supplies while catching up on local news. Residents could also connect with others by sharing content through social sharing options available at community gatherings.

The humble country store stood as more than a merchant—it was Canelo’s living, breathing community center.

These buildings fostered community interactions that defined frontier life, becoming unofficial town squares where ranchers and miners gathered. Today, visitors traveling through Santa Cruz County can still see remnants of this once-thriving community.

The Historic Canelo Schoolhouse: Education on the Frontier

When you visit Canelo today, you’ll find the rare 1912 adobe schoolhouse standing as testimony to frontier education, built with local materials and listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1991.

The one-room structure initially served about 20 students from homesteader families before evolving into a vibrant community hub for dances, political meetings, and plays until its closure in 1948.

As children and teachers once rode horses to this isolated outpost of learning, the surrounding 2-acre property was thoughtfully fenced to keep their mounts secure during school hours. Miss Fern Bartlett, the first teacher at Canelo School, made a daily eight-mile journey on horseback to reach her students. This approach to education resembled the Little Outfit Schoolhouse model where ranch school education emphasized both academics and Western traditions.

1912 Schoolhouse Construction

As dawn broke over the Arizona Territory in 1912, the foundations were laid for what would become the last surviving one-room adobe schoolhouse in the state.

Local craftsmen molded adobe bricks from the earth beneath their feet, creating a structure that embodied frontier self-reliance.

The modest 42 by 22 foot building rose with its low-pitched front gable roof and distinctive bell tower, standing as a tribute to historical architecture of the Southwest.

Its adobe techniques—thick earthen walls later plastered for protection—kept students cool in summer and warm in winter.

Cedar roofing and oak structural elements completed this utilitarian masterpiece.

A proper disambiguation page would have helped visitors distinguish this historic Canelo schoolhouse from other places sharing the Canelo name across the region.

You’ll notice the careful planning in its design—fully fenced to accommodate horses, with a woodshed that expanded as needs grew, perfectly suited to frontier life.

Community Hub Evolution

Though built primarily for education, the Canelo schoolhouse quickly evolved into the beating heart of frontier social life.

You’d find much more than reading and arithmetic within these adobe walls—this was where your community truly formed.

At the schoolhouse, you’d cast your vote in local elections, dance to fiddle music (later replaced by a player piano), and gather for both celebrations and funerals.

These community gatherings transformed isolated homesteaders into neighbors with shared purpose.

The 2-acre property welcomed horses, while its simple yet sturdy construction created space for cultural events from political meetings to theatrical performances.

As student numbers dwindled from 20 to just one by 1948, the building’s importance as a civic hub remained—a symbol of frontier resilience that earned its place on the National Register of Historic Places.

Miss Fern Bartlett, the first teacher, committed to education by traveling eight miles by horse daily to reach her students at the newly built schoolhouse.

Rural Education Challenges

Education at Canelo’s schoolhouse revealed the stark realities of frontier learning. You’d find students traveling miles across rugged terrain, sometimes on horseback, just to reach this educational outpost.

By the 1940s, rural schooling faced an existential threat as population shifted from small homesteads to expansive ranches, eventually leaving just a single student by 1948.

The educational isolation meant making do with limited resources—one teacher instructing multiple grades simultaneously within a single 42-by-22-foot room. Like many of the approximately 200,000 one-room schoolhouses operating in the early 1900s, Canelo’s school represented a vital community institution despite its limitations. This educational approach mirrored other historical schools like the Strawberry Schoolhouse, where one teacher managed eight different grade levels.

Despite these challenges, the schoolhouse adapted, modernizing with exterior plastering and adding a woodshed in the 1920s-30s. The player piano that replaced the original organ symbolized the community’s determination to provide cultural education despite their remoteness.

This struggle between frontier limitations and educational aspirations defined Canelo’s scholastic experience.

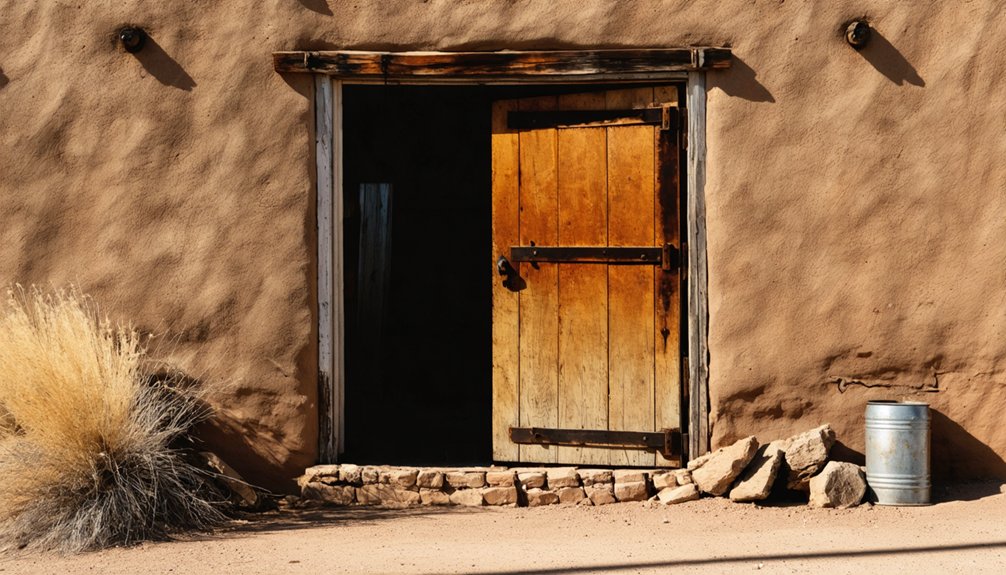

Canelo Guard Station: Architecture and Conservation Legacy

The Canelo Ranger Station stands as a masterpiece of Depression-era Southwestern architecture, with construction beginning in November 1932 just before the Civilian Conservation Corps was fully established.

Its adobe brick construction exemplifies regional authenticity while providing exceptional thermal properties. The architectural significance lies in thoughtful adaptations like the wooden gabled roof on the office building—designed to harmonize with the forest landscape rather than following typical flat adobe designs.

When you visit today, you’ll find the station’s careful conservation strategies have preserved its historic fabric while accommodating modern needs.

The CCC’s contributions of stone walls and infrastructure improvements remain visible across the complex. As a National Register of Historic Places site, it connects you to both Forest Service history and the pioneering heritage of Canelo.

Black Oak Cemetery: Final Resting Place of Canelo’s Pioneers

As you wander among the weathered markers at Black Oak Cemetery, you’ll find the graves of Canelo’s founding families arranged in a traditional open layout that reflects the democratic spirit of frontier communities.

The cemetery’s notable burials include several generations of ranchers, miners, and homesteaders who shaped this remote corner of Arizona through their tenacity and vision. Local families still maintain the tradition of Decoration Day each spring, when descendants gather to place wildflowers and mementos on the graves while sharing stories that keep their ancestors’ memories alive.

Notable Burials

Silent sentinels of stone mark the hallowed ground of Black Oak Cemetery, where Canelo’s pioneers have found their eternal rest since the early 1900s.

You’ll discover over 260 documented interments reflecting the area’s rich ranching heritage and pioneer legacies.

Among these markers lie the Anderson family, with William and Ruth representing early settlement, alongside the Amend and Pyeatt families who shaped Canelo’s development.

The cemetery’s significance extends beyond mere burial grounds—it’s a historical chronicle of community builders.

Military veterans like Joseph Pyeatt, who served in WWII, rest among influential figures such as Addie M. Parker, a noted rancher and stockman.

These graves tell stories of sacrifice, perseverance, and dedication that formed this frontier community, preserving the memory of those who transformed wilderness into home.

Cemetery Layout

Beyond the stories of those who rest within its grounds, Black Oak Cemetery‘s physical arrangement provides a window into Canelo’s pioneer sensibilities. The cemetery design follows a straightforward grid pattern that respects the natural contours of this peaceful site, situated about a mile above sea level within Coronado National Forest.

As you walk the grounds, you’ll notice approximately 269 graves arranged in an orderly fashion, with family plots clearly demarcated—a reflection of the community’s strong kinship ties.

Grave organization reflects both chronological burial patterns and family associations, showing how Canelo evolved from settlement to community. The modest layout, combining marked and unmarked sites with varying headstone qualities, perfectly captures the pragmatic yet respectful approach of Arizona’s early settlers to honoring their dead.

Memorial Traditions

While standing amid the whispering pines of Black Oak Cemetery, you’ll feel the profound connection to Canelo’s early pioneers through the memorial traditions that have defined this sacred ground since the early 1900s.

These practices of communal remembrance continue to honor those granted free burial through the special 1917 Forest Service permit.

Pioneer descendants maintain three essential traditions:

- Quiet reflection visits that embrace the cemetery’s serene forest setting

- Preservation of traditional markers and inscriptions rich with memorial symbolism

- Collaborative record-keeping that documents genealogies and burial histories

You’ll notice how the cemetery’s memorial customs mirror southwestern pioneer values—simplicity, reverence for nature, and deep respect for ancestral sacrifice.

These traditions transform this peaceful corner of Coronado National Forest into living heritage rather than merely a ghost town relic.

Natural Surroundings: Geography and Climate of Turkey Creek Valley

As you journey through the tranquil expanse of Turkey Creek Valley, you’ll discover a landscape dramatically shaped by ancient volcanic forces dating back to the Oligocene epoch, some 26.5 million years ago.

This remarkable volcanic landscape resulted from a catastrophic eruption that formed the Turkey Creek Caldera, spanning 12 miles in diameter.

Today, you’ll find yourself wandering at about 5,250 feet elevation, where the semi-arid climate offers respite from harsh desert conditions.

Summer monsoons breathe life into the normally dry creek beds, while the valley’s unique position creates moderate temperatures year-round.

Saguaros stand sentinel alongside desert scrub and grasslands, adapting to the rhythms of drought and rainfall that define this freedom-filled wilderness.

The Slow Decline: From Active Community to Ghost Town Status

The human settlement of Canelo stands in stark contrast to the timeless volcanic landscape that surrounds it.

The human settlement of Canelo erupts from history’s ash, a fragile testament against nature’s unyielding canvas.

You’ll find that this once-vibrant community experienced a gradual unraveling despite remarkable community resilience. The economic shifts began with subtle warning signs:

- The post office closure in 1924 marked the first major institutional loss

- Mining operations slowed, triggering resident departures and vanishing job opportunities

- The school’s closure in 1948 signaled the final phase of community dissolution

What remains today tells a story of adaptation and surrender.

The schoolhouse and Guard Station—both now on the National Register of Historic Places—stand as silent sentinels of a different era.

While most buildings have returned to the earth, their legacy persists in the memories they hold.

Preservation Efforts: Saving Canelo’s Historical Structures

Perched on the cusp of oblivion, Canelo’s few remaining structures have found champions in a network of dedicated preservationists who recognize their irreplaceable historical value.

The Canelo Guard Station and School—both listed on the National Register of Historic Places—stand as monuments to Depression-era architecture and early frontier education.

HistoriCorps leads the Canelo preservation charge, partnering with Coronado National Forest to restore the Guard Station using period-appropriate techniques. Their meticulous historical restoration work focuses on adobe masonry, authentic flooring, and removing historically inaccurate elements.

Meanwhile, The Nature Conservancy protects the adjacent Canelo Hills Cienega Preserve, safeguarding not just buildings but the ecological context that shaped this once-thriving community.

Local residents contribute by maintaining historic adobe structures, ensuring Canelo’s story isn’t lost to time.

Visiting Canelo Today: What Remains of a Forgotten Arizona Community

Tucked away in eastern Santa Cruz County where the Canelo Hills meet the northern Huachuca Mountains, Canelo’s ghostly remnants invite modern explorers into Arizona’s vanished frontier past.

As you wander along Turkey Creek, you’ll encounter preserved pieces of pioneer life amid abundant Canelo wildlife—hawks soaring overhead as deer disappear into woodland shadows.

Three must-see structures for ghost town photography enthusiasts:

- Canelo Guard Station (1932) – With its distinctive gabled roof designed to complement the forested surroundings

- Canelo School (1912) – Standing proudly on the National Register of Historic Places

- Former general store and post office – Now a private residence but still showcasing early 20th-century rural architecture

You’ll find this time-frozen settlement via State Route 83, where the cinnamon-colored hills that gave Canelo its name still watch over these weathered relics of frontier determination.

Frequently Asked Questions

Are There Any Paranormal Sightings Reported in Canelo’s Historical Buildings?

You won’t find documented ghost sightings in Canelo’s buildings. Unlike Jerome or Bisbee, this frontier outpost hasn’t yielded substantiated historical hauntings, though whispers of Apache spirits linger in the surrounding hills.

What Indigenous Tribes Inhabited the Area Before Canelo’s Settlement?

As you walk ancestral paths beneath sunlit pines, you’re treading where Yavapai people once roamed. The Hohokam culture flourished nearby, while Apache tribes—particularly Western and Dilzhe’e bands—later dominated these rolling grasslands you’d call freedom.

Did Any Famous Outlaws or Notorious Incidents Occur in Canelo?

You’ll find no famous outlaws roamed Canelo’s tranquil grounds. Unlike other Arizona ghost towns, Canelo’s history reveals no notorious incidents—just quiet homesteading days marked by forestry and community development.

Were There Mining Operations or Other Industries Beyond Ranching?

Yes, you’d have found mining complementing Canelo’s ranching economy. Though less prominent, mining techniques from the early 1900s left their mark, having economic impact alongside community facilities like the post office and schoolhouse.

How Did Residents Access Healthcare in Early Canelo?

You’d rely on family remedies and neighbors’ help. Healthcare access meant arduous journeys to distant towns, as early clinics were nonexistent. Military surgeons and traveling doctors provided rare professional care.

References

- https://theclio.com/entry/54976

- https://www.arizonahighways.com/article/arizona-ghost-towns

- https://www.hipcamp.com/journal/camping/arizona-ghost-towns/

- https://www.ghosttowns.com/states/az/canelo.html

- https://arizonakateblog.wordpress.com/2023/09/12/canelo-arizona/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Canelo_Ranger_Station

- https://caneloproject.com/more-monsoon-driving/

- https://kids.kiddle.co/Canelo

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_ghost_towns_in_Arizona

- https://kids.kiddle.co/List_of_ghost_towns_in_Arizona