You’ll find Cayuga’s ghost town remains along Oklahoma’s Elk River, where it flourished in the late 1800s as a wagon manufacturing hub. Founded in 1884, the town grew around Mathias Splitlog’s four-story wagon factory and limestone quarries, serving settlers and ranchers. After a devastating 1913 fire and missed railroad connections, Cayuga declined, though its iconic limestone Splitlog Church still stands as a symbol of its frontier spirit. The town’s hidden stories wait among its rolling hills and wooded valleys.

Key Takeaways

- Cayuga, Oklahoma, founded in 1884, served local settlers with a post office and businesses before declining into a ghost town.

- The town’s economic decline began in the 1910s due to missing railroad connections and families seeking opportunities elsewhere.

- Agricultural mechanization and bypassed transportation routes contributed significantly to Cayuga’s transformation into a ghost town.

- The Splitlog Church, built in 1893, remains as one of the few surviving structures after the devastating 1913 fire.

- Local preservation societies work to protect Cayuga’s remaining historical structures and document its transition from bustling town to abandonment.

Native Origins and the Splitlog Legacy

While the Cayuga people originally thrived along New York’s Cayuga Lake as part of the Iroquois Confederation, their journey to Oklahoma began through a series of forced migrations.

You’ll find their earliest roots as “People of the Great Swamp,” where they maintained four distinct clan groups and a population of 1,500 by 1660.

After the American Revolution split their allegiances, you’ll see how Sullivan’s scorched-earth campaign of 1779 forced many Cayuga to flee to Ohio and Canada. The Pickering Treaty in 1794 formalized their land cessions to the United States.

Sullivan’s brutal campaign during the Revolution scattered the Cayuga people, sending them fleeing northward to Canada and westward to Ohio.

The Cayuga people were historically governed by the Great Law of Peace, which established principles of democracy and diplomacy among their nation.

By the 1830s, they’d been pushed into Indian Territory, where they’d later merge with the Seneca.

In Oklahoma, Pierre Splitlog’s business ventures helped these displaced Cayuga adapt and survive, fostering economic development that strengthened their new community despite being far from their ancestral lands.

A Thriving Industrial Past

If you’d visited Cayuga in the early 1900s, you’d have heard the steady chugging of steam-powered wagon manufacturing facilities echoing through the valley.

The town’s limestone quarries employed dozens of workers who extracted high-quality stone for regional construction projects. The area became part of Delaware County when Oklahoma achieved statehood in 1907.

These industrial operations, situated along the banks of Spavinaw Creek, formed the economic backbone of Cayuga until the 1920s when newer transportation technologies and changing market demands led to their decline. Many of the workers lived together in traditional bark-covered longhouses.

Steam-Powered Wagon Production

In the early 1890s, Mathias Splitlog transformed Cayuga into a pioneering industrial hub by establishing a massive four-story wagon factory in Indian Territory. His vision embraced steam wagon innovations and industrial craftsmanship, producing diverse vehicles from buggies to two-seated hacks. His mechanical genius was evident in his factory designs, having previously built steamboats during the Civil War.

The factory’s impact on Cayuga was revolutionary, featuring:

- A complete industrial complex with sawmill, gristmill, and blacksmith operations

- Advanced manufacturing capabilities that reduced dependency on distant suppliers

- Competitive wages that attracted skilled workers and grew the local population

You’d find the factory at the heart of Cayuga’s economy, where steam-powered production techniques mirrored developments happening in major manufacturing centers. Following industry trends of the time, the factory incorporated locomotive type boilers in their steam wagon designs.

The facility survived the devastating 1913 fire that destroyed most of the town, standing as a monument to Splitlog’s industrial legacy.

Limestone Quarry Operations

During the late 1800s, Cayuga’s limestone quarries emerged as a cornerstone of Oklahoma’s industrial development, with extensive deposits stretching across the region’s marine-formed geological beds.

You’d find workers using hand drills and black powder for limestone extraction, while horses and mules hauled the valuable stone from the quarry faces.

As technology advanced, you’ll notice how quarrying techniques evolved from manual labor to industrial-scale operations.

The limestone proved crucial for concrete production, railroad ballast, and road construction throughout Oklahoma.

The Santa Fe Railroad particularly relied on Cayuga’s crushed stone for its expanding rail network. Early mining operations used simple vertical kilns to process the limestone for construction and other industrial uses.

Even as newer materials emerged in the late 20th century, the quarries remained essential for cement and lime production, supporting construction across the region. The quarrying process required hundreds of laborers to extract and transport the massive limestone blocks during peak operations.

The Iconic Splitlog Church

The iconic Splitlog Church, constructed in 1893 by Seneca Chief Mathias Splitlog and his wife Eliza, stands as a tribute to Native American religious heritage in Cayuga, Oklahoma.

You’ll find this remarkable gray limestone structure perched on a hill overlooking the Elk River and Grand Lake, its tall steeple visible from nearly a mile away. The doorway features fifteen carved stones displaying unique Indian symbols. The original Belgian-cast bell was first tolled to honor Mrs. Splitlog’s memory.

- Original Catholic furnishings included stained glass windows, an altar, and bell

- A picturesque cemetery surrounds the church, featuring mid-1880s grave markers

- The building survived Cayuga’s 1913 fire while most of the town burned

Despite facing vandalism between 1930-1953, including dynamiting by treasure hunters, the church was restored through R.A. Sellers Sr.’s dedication.

Today, it’s maintained as a symbol of religious freedom, serving multiple denominations and welcoming visitors year-round.

Life Along the Rivers

You’ll find that river commerce thrived along the waterways near Cayuga, with steamboats regularly stopping to trade goods and transport people in the mid-1800s.

The riverside communities established docks and trading posts where local residents exchanged agricultural products, furs, and crafts with merchants traveling the river routes.

The waterfront settlements flourished until the arrival of railroads in the late 1800s shifted commerce away from the rivers, leading to the gradual decline of these once-bustling river ports.

River Commerce Activities

Rivers played a significant role in shaping commerce activities near Cayuga, Oklahoma, serving as indispensable transportation corridors before modern infrastructure existed.

You’d find bustling river trade along these waterways, where canoe transport was essential for moving goods between settlements and trading posts.

- Fur traders navigated seasonal flood patterns to ship pelts downstream, maximizing their trading opportunities during high water periods.

- Local merchants established strategic outposts at river crossings, creating temporary markets where tribes exchanged agricultural products and manufactured goods.

- Native communities maintained extensive trade networks through waterways, bartering important items like salt, iron tools, and blankets.

The rivers’ economic importance extended beyond mere transport – they created natural hubs where different cultures met to conduct business, fostering a dynamic trading environment that supported the region’s growth and survival.

Waterway Communities Flourished

Along Oklahoma’s fertile riverbanks, diverse communities of Plains Villagers, Wichita, and Caddoan peoples established thriving settlements that shaped the region’s cultural landscape.

You’ll find evidence of how they masterfully combined waterway agriculture with hunting and gathering, constructing grass houses near streams where the soil was easier to till.

These strategic river locations weren’t just about farming – they became vibrant hubs of river trade and cultural exchange. As you explore these waterways, you’ll notice how indigenous peoples developed complex economic networks, cultivating corn, beans, and squash while maintaining fishing and hunting practices.

The rivers’ seasonal rhythms dictated their activities, from planting times to trading seasons. Multiple tribal groups in the Washita River Basin created interconnected communities that adapted and thrived, making the most of these life-sustaining waterways.

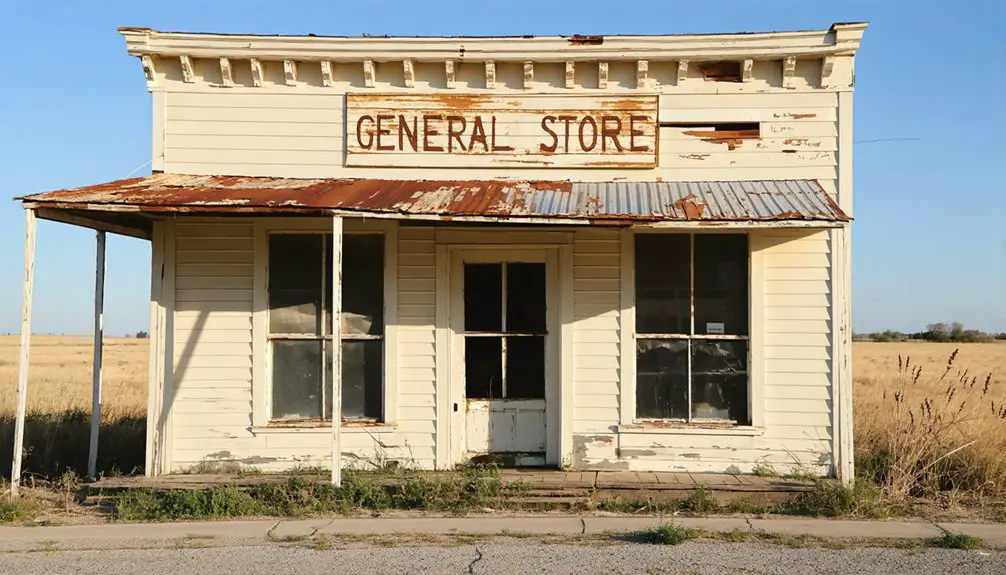

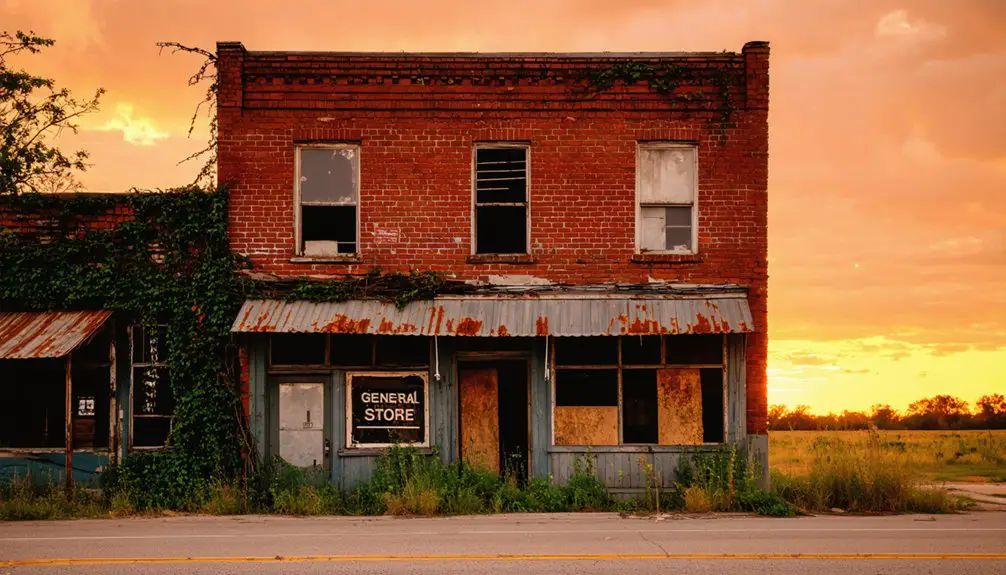

Rise and Decline of a Frontier Town

Founded in 1884 during Oklahoma’s frontier expansion, Cayuga emerged as a small agricultural and trading community in Delaware County.

You’ll find a town that once served local settlers and ranchers, with a post office and businesses supporting modest population growth through the turn of the century.

Despite initial promise, Cayuga’s trajectory shifted toward economic isolation due to:

- Missing vital railroad connections while neighboring towns prospered from rail access

- Declining population starting in the 1910s as young families sought opportunities elsewhere

- Closure of essential institutions like schools and churches by the early 1900s

The town’s fate was sealed when agricultural mechanization reduced labor needs and transportation routes bypassed the community.

Without major industries or natural resource booms, Cayuga gradually transformed into the ghost town you’ll discover today.

Natural Beauty and Local Landscape

The natural splendor of Cayuga unfolds across northeastern Delaware County’s rolling hills and wooded valleys.

You’ll find yourself at 886 feet elevation, surrounded by natural landscapes that blend mixed hardwood forests with open prairies. The Elk River winds through the terrain, creating vibrant riparian corridors where you can spot beavers, otters, and diverse bird species in their natural habitat.

The area’s ecological diversity shines through its seasonal transformations. In spring and summer, wildflowers dot the gentle slopes while native grasses sway in the breeze.

You’re free to explore the region’s network of springs, creeks, and tributaries that feed into the Elk River. The untamed wilderness still beckons with opportunities for hiking, fishing, and wildlife watching amid the unspoiled beauty of Oklahoma’s Ozark Plateau foothills.

Preserving Cayuga’s Historical Heritage

Since preserving Cayuga’s rich history requires dedicated effort, local historians and preservation societies have implemented thorough strategies to protect this Oklahoma ghost town’s heritage. Through historical preservation initiatives, you’ll find carefully documented records, including archival photographs, land deeds, and oral histories that paint a vivid picture of the town’s past.

Community involvement plays a crucial role in protecting Cayuga’s legacy through:

- Volunteer-led stabilization of remaining structures using period-accurate materials

- Educational programs and guided tours that share the town’s story with visitors

- Fundraising campaigns that support ongoing preservation projects and cemetery maintenance

You can explore Cayuga’s heritage through interpretive displays and heritage trails that connect you to Oklahoma’s broader historical narrative while ensuring these precious remnants endure for future generations.

Frequently Asked Questions

Are There Any Guided Tours Available to Explore Cayuga’s Historic Sites?

Want to explore this historic site? You won’t find guided tours available, but you’re free to conduct your own guided exploration of Cayuga’s historically significant locations through self-directed visits.

What Paranormal Activities Have Been Reported in the Abandoned Buildings?

You’ll encounter ghost sightings near old windows, shadowy figures in period clothing, and unexplained noises like footsteps and whispers. EMF readings spike inside buildings, while objects mysteriously move on their own.

Can Visitors Access the Cemetery for Genealogical Research?

Like stepping through history’s gate, you’ll find cemetery access available for genealogical research – no special permits needed. You can freely explore the grounds, document headstones, and trace your family’s past.

What Artifacts From Cayuga’s Industrial Era Have Been Preserved?

You’ll find limited Cayuga artifacts from the industrial era, with only Splitlog Church standing as the main preserved structure. The church’s original bell now resides at St. Catherine’s in Nowata.

Is Metal Detecting or Artifact Collecting Allowed in Cayuga?

You’ll need permits for metal detecting on public lands, and written permission from private landowners. Due to artifact preservation regulations, most collecting isn’t allowed without proper authorization from relevant authorities.

References

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Splitlog_Church

- http://genealogytrails.com/oka/delaware/bio_splitlog.html

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_ghost_towns_in_Oklahoma

- http://www.ghosttowns.com/states/ok/cayuga.html

- https://www.okhistory.org/publications/enc/entry?entry=DE010

- https://www.legendsofamerica.com/cayuga-tribe/

- https://cayuganation-nsn.gov/about/history-and-culture/

- https://sctribe.com/history/07-02-2015/guide-indian-tribes-ok-cayuga

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cayuga_people

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Seneca–Cayuga_Nation