You’ll find Centennial, Wyoming at 8,076 feet elevation, where gold mining dreams of the 1870s have transformed into a vibrant mountain community. While I.P. Lambing’s 1875 discovery sparked mining fever and speculation, the town’s brief gold rush produced only 4,000 ounces before operations ceased. Today, 400 residents call this historic mining settlement home, preserving its pioneer spirit amid the dramatic backdrop of Sheep Mountain and the Medicine Bow Range. The town’s colorful past holds many more frontier tales.

Key Takeaways

- Centennial, Wyoming is not a ghost town, as it maintains an active population of approximately 400 residents in a close-knit community.

- The town experienced a mining boom-bust cycle after I.P. Lambing’s 1875 gold discovery, producing only 4,000 ounces before operations ceased.

- Failed mining investments and promotional schemes, including the Mountain View Hotel, reflect the town’s historical struggle with economic sustainability.

- Unlike many abandoned Western mining towns, Centennial successfully transitioned to ranching and logging after mining declined.

- The community remains economically stable with high homeownership rates and a median household income exceeding $103,000.

Discovering the Mountain Gateway: Location and Natural Setting

A mountain gateway to adventure, Centennial, Wyoming sits nestled in the southeastern corner of the state, approximately 27 to 45 miles west of Laramie.

You’ll find this high-elevation outpost perched at 8,076 feet in the dramatic Centennial Valley, where geological features create a stunning shift between prairie and alpine environments. The town’s extreme elevation means snow is possible year-round.

The town’s natural setting showcases breathtaking contrasts, with Sheep Mountain rising to the east and the towering Medicine Bow Range dominating western views. Originally established as a small mining settlement, the town grew after gold was discovered in the nearby mountains.

Wyoming Highway 130, known as the Snowy Range Scenic Byway, winds through this mountain paradise, offering scenic overlooks and access to the Medicine Bow National Forest.

The scenic byway snakes through pristine wilderness, beckoning travelers to explore the majestic landscapes of Medicine Bow.

The Little Laramie River threads through the valley, creating a verdant oasis where the rugged peaks of Snowy Range, reaching over 12,000 feet, command the horizon.

From Tie Camps to Town: Early Pioneer Settlement

Before European settlers established permanent roots in Centennial Valley, indigenous peoples including the Cheyenne, Arapaho, Ute, and Lakota tribes called this resource-rich corridor home.

French traders began exploring the area’s rich fur resources in the 1740s, marking the first European presence in the region.

You’ll find that settler motivations first emerged around 1868 when tie camps sprang up to supply the Union Pacific Railroad with timber, though conflicts with Native Americans often forced these camps to relocate.

The economic shifts that shaped Centennial began with the Homestead Act of 1862, which drew ranchers like Pete Christiansen to stake their claims.

I.P. Lambing’s discovery of the Centennial Mine in 1875 sparked the area’s first significant mining activity.

While tie camps represented temporary settlement, permanent ranching operations soon formed the community’s backbone.

Mining speculation in 1876, the early 1900s, and 1920s drove further development, including the Mountain View Hotel, though these booms proved more optimistic than profitable.

Golden Dreams and Mining Ventures

You’ll find the story of Centennial’s mining history reflects the boom-and-bust cycle common to Western gold rushes, beginning with I.P. Lambing’s 1875 discovery that sparked initial excitement but ended abruptly when miners hit a fault line in 1877.

The mine produced approximately 90,000 dollars worth of free milling gold during its brief operational period. Subsequent investment schemes in 1902 and the 1920s tried to revive the district’s mining prospects, leading to infrastructure developments like the Mountain View Hotel and railroad extensions to support what promoters hoped would become a thriving mining economy.

Despite these ambitious efforts and the district’s eventual production of 4,000 ounces of gold, Centennial’s mining ventures proved more notable for their promotional schemes than their profitable yields.

Mining Booms and Busts

When gold was discovered along Centennial Ridge in 1874, prospectors rushed to establish what would become the Centennial Mining District the following year.

You’ll find that initial mining operations focused on underground lode veins, with production starting in 1876 but ending abruptly in 1877 when the vein faulted.

Mining speculation drove three distinct boom periods – 1876, early 1900s, and the 1920s – though none produced substantial returns.

The district’s total gold production remained modest at around 4,000 ounces. Economic downturns followed each boom as ore discoveries failed to meet expectations.

While promoters and media hyped the area’s potential, most ventures proved unprofitable.

The Laramie, Hahn’s Peak, and Pacific Railway even arrived in 1907, but by then, the main mining excitement had already faded.

Gold Rush Investment Schemes

The allure of gold drove ambitious investment schemes in Centennial’s mining district, starting with I.P. Lambing’s discovery in 1875. Under Stephen W. Downey’s leadership, mining promotions attracted speculative investments through exaggerated claims and flashy marketing tactics.

You’ll find evidence of these promotional efforts in the Mountain View Hotel, an $8,000 showpiece built to lure investors. Gustav Sundby organized regular excursions from the hotel for potential investors. After the Union Pacific Railroad arrived in 1867, Cheyenne miners flocked to the region seeking their fortunes.

The mining district’s marketing campaign reached its peak when a gold nugget was displayed at the 1876 Philadelphia Exposition, drawing national attention. However, the reality didn’t match the hype – by 1877, gold veins had either depleted or hit geological faults.

Despite media manipulation and overstated reports of wealth, subsequent booms in 1902 and 1923-1924 failed to deliver lasting prosperity. These schemes left many investors with empty pockets while the town eventually turned to ranching and logging for survival.

Fault Lines End Dreams

Beneath Centennial’s promising surface lay geological fault lines that would ultimately shatter miners’ golden dreams.

You’ll find that when the initial gold vein hit a major fault line in 1877, just two years after its discovery, miners couldn’t locate its continuation despite desperate attempts. These fault line impacts wreaked havoc on underground stability and disrupted precious metal deposits throughout the region.

The mining disruptions triggered a chain reaction of economic failures.

You’d have seen how quickly the promising ventures turned into failed speculative schemes, leading to abandoned mines and disappointed investors.

What began as a rush of optimism in 1875 devolved into yet another western mining disappointment, leaving behind empty hotels and scattered dreams – all because nature’s deep fractures had the final say in Centennial’s mining destiny.

Native American Encounters and Frontier Conflicts

You’ll find that Centennial Valley’s history includes significant Native American presence, with tribes like the Cheyenne and Arapaho using the area for hunting, gathering wood, and as a trade corridor.

When railroad expansion brought a tie camp to the region in 1868, tensions escalated into direct conflict, culminating in a 1869 raid that drove workers from the camp.

The Cheyenne and Arapaho formed a lasting alliance around 1811, leading to greater control over their territories. The U.S. military responded by establishing protective forts throughout the territory, marking a period of increased confrontation between Native peoples defending their traditional lands and the wave of settlers moving west. Colonel Frank Skimmerhorn led brutal military campaigns against the Native American tribes, intensifying the violence in the region.

Traditional Land Use Patterns

Original inhabitants of Centennial Valley included the Cheyenne, Arapaho, Ute, and Lakota tribes, who maintained intricate patterns of seasonal migration and resource utilization throughout the region.

You’ll find their traditional resource use reflected in how they followed game herds across the valley, establishing summer camps while harvesting local materials like wood for their teepees and bows.

The Shoshonis and Crows were also known to inhabit this territory before white settlers arrived.

These tribes weren’t confined to one location – they’d move freely through established trade routes, connecting with other Native peoples and eventually European fur traders.

Their seasonal migration patterns showed deep understanding of the land’s rhythms, as they’d relocate based on available resources and weather conditions.

This traditional way of life continued until railroad expansion and homesteading legislation disrupted their established patterns of movement and resource gathering.

Tie Camp Raids 1869

During the turbulent summer of 1869, warriors who’d split from Red Cloud’s band launched a series of coordinated attacks known as the Tie Camp Raids across Wyoming’s frontier settlements. Their raiding strategies targeted labor camps, settler encampments, and military units protecting railroad construction, aiming to disrupt supply lines and resist encroachment on traditional lands.

These military engagements included a July 28 attack on a paymaster wagon between Forts Reno and Fetterman, an August 28 assault on Laycock’s woodchopper camp, and a September 15 raid near Cooper Lake that left one dead and three captured.

That same day, approximately 300 warriors confronted Lieutenant Spencer’s Fourth Infantry detachment near Whiskey Gap. While U.S. troops responded swiftly from frontier forts, the raiders often successfully evaded pursuit through difficult terrain.

Territorial Protection and Forts

As westward expansion intensified in the late 1860s, Wyoming’s territorial protection relied heavily on a network of military forts strategically positioned along major migration routes and railroad lines.

You’ll find that Fort D.A. Russell, Fort Sanders, and Fort Fred Steele formed a protective triangle safeguarding Union Pacific Railroad workers and settlers from Native American raids.

Fort Laramie served as the region’s most significant military and diplomatic outpost, while Fort Phil Kearny became notorious for the bloody Fetterman Fight of 1866.

At Wind River, Camp Augur (later Fort Washakie) provided essential territorial protection for both settlers and cooperative Native American tribes.

These military forts weren’t just defensive positions – they represented federal authority and enabled the region’s rapid development by securing critical transportation corridors and settlement zones.

The Rise and Fall of a Mining Community

When prospectors discovered gold along Centennial Ridge in 1874, they launched a series of mining booms that would define the town’s turbulent history.

Led by I.P. Lambing and Stephen W. Downey, the Centennial Mining District gained national attention when it exhibited a gold nugget at the 1876 Philadelphia Exposition.

You’ll find the town’s cultural heritage marked by three distinct mining rushes in 1876, 1902, and 1923-1924.

Despite optimistic promotion and media hype, none delivered lasting success. The critical blow came when miners hit a fault in the main gold vein in 1877.

While the Douglas Creek Mining District nearby produced about 4,000 ounces of gold, Centennial’s economic shifts moved toward ranching and logging.

The arrival of the railroad in 1907 came too late to save the mining operations, though remnants like the Mountain View Hotel still stand as evidence of those ambitious times.

Architectural Legacy and Historic Landmarks

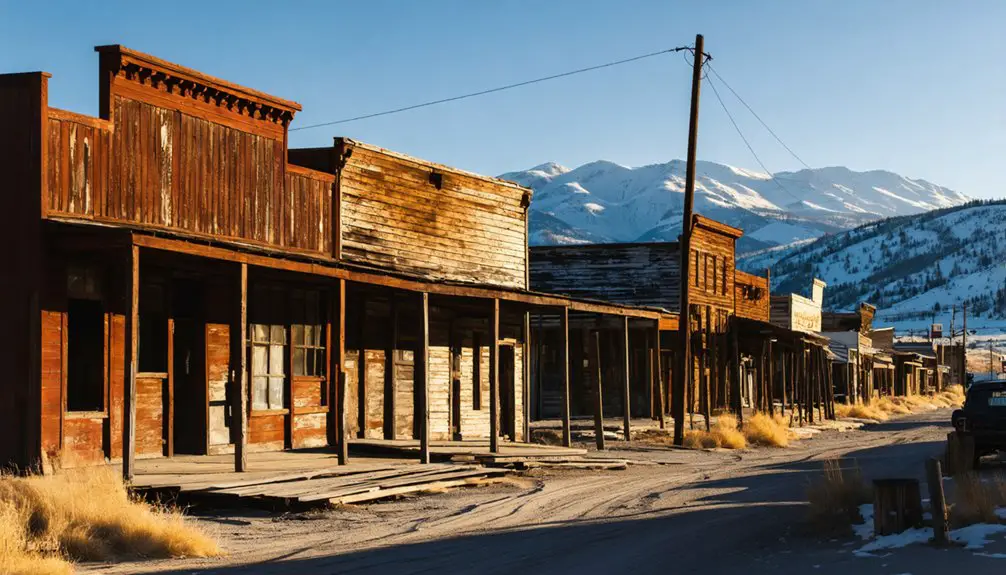

The architectural remnants of Centennial’s mining era tell a compelling story of frontier ambition and resourcefulness.

Weathered buildings and abandoned mines echo the pioneering spirit that once fueled Centennial’s ambitious quest for mineral wealth.

You’ll find the Mountain View Hotel standing as the town’s crown jewel, its two-story frame reflecting the architectural styles common to early 1900s mining towns.

Throughout the area, you’ll discover deteriorating log cabins, mine buildings, and sawmills that showcase the practical, utilitarian construction methods of the frontier era.

Historic preservation efforts have saved several key structures, with some relocated to the Grand Encampment Museum.

The Gold Hill mining group site features extensive underground workings and surface buildings, while original cemeteries with weathered gravestones document the community’s struggles.

These landmarks, built primarily from local timber and stone foundations, stand as evidence to Centennial’s brief but significant mining boom.

Life in Modern-Day Centennial Valley

Modern-day Centennial Valley presents a unique portrait of rural Wyoming life, where approximately 400 residents enjoy a close-knit community characterized by high homeownership rates and substantial household incomes.

The community dynamics reflect an older, established population with a median age of 63, where you’ll find many residents working from home or commuting an average of 27 minutes.

You’ll discover a primarily English-speaking enclave where property values hover around $495,500, and most households own three vehicles.

Modern life in the valley centers around single-family homes, with 95% of residents owning their properties.

While the population density remains low at under 20 people per square mile, the valley’s residents maintain strong economic stability with median household incomes exceeding $103,000.

Frequently Asked Questions

What Happened to the Descendants of Original Centennial Settlers?

You’ll find descendant stories scattered as families moved to Laramie, Casper, and western cities, leaving their family legacies behind when mining declined and railroad jobs vanished in search of better opportunities.

Are There Any Active Paranormal Investigations in Centennial’s Abandoned Buildings?

You won’t find organized paranormal activity or ghost tours at this location currently. While Wyoming has active ghost hunting scenes elsewhere, there’s no documented evidence of formal investigations in these abandoned buildings.

What Was the Total Gold Production Value From Centennial’s Mines?

You’ll find the historical gold mining value was approximately $93,000 in 1870s dollars, based on 4,500 ounces produced. Today’s equivalent would be roughly $9 million at current prices.

Can Visitors Legally Collect Artifacts From the Ghost Town Site?

You can’t legally collect artifacts from any ghost town sites without permits due to strict legal regulations. These preservation laws protect historical resources, and violations can result in hefty fines or criminal charges.

Which Original Centennial Buildings Are Still Safe to Enter Today?

You’ll find the Mountain View Hotel is the only verified safe entry point, given its historical preservation status and architectural significance. Other original structures aren’t confirmed safe for public access.

References

- http://www.wyomingtalesandtrails.com/ghost2.html

- https://centenniallibrary.net/community.html

- https://www.legendsofamerica.com/wy-ghosttowns/

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ErvYfYCW0qk

- https://travelwyoming.com/blog/stories/post/5-wyoming-ghost-towns-you-need-to-explore/

- https://en.wikivoyage.org/wiki/Centennial_(Wyoming)

- https://www.visitlaramie.org/blog/post/the-fascinating-history-of-centennial-wyoming/

- https://www.wyo.gov/about-wyoming/wyoming-history/chronology

- https://www.wyo.gov/about-wyoming/wyoming-history

- https://westernmininghistory.com/mine-detail/10038157/