Chambless began as a crucial oasis along Route 66 in the 1920s, established by James and Fannie Chambless. This Mojave Desert stop thrived with a gas station, café, motel, and grocery store until Interstate 40‘s 1973 construction diverted traffic. Today, you’ll find concrete ruins and abandoned buildings that tell the story of America’s highway culture. Recent preservation efforts, including the restoration of Roadrunner’s Retreat, offer a glimpse into the town’s fascinating past.

Key Takeaways

- Chambless originated in the 1920s as a Route 66 oasis with a store, gas station, café, motel, and auto shop for desert travelers.

- The town was established by James and Fannie Chambless, who created a desert refuge featuring a rose garden and fish pond.

- Constructed with adobe bricks and hollow tile for desert conditions, remaining concrete structures showcase practical Mojave desert architecture.

- Interstate 40’s construction in 1973 diverted traffic away from Chambless, transforming it into an abandoned ghost town.

- Preservation efforts include restoring the 1962 Road Runner’s Retreat sign and rehabilitating nine concrete cottages with National Park Service grants.

The Rise of a Desert Oasis Along Route 66

While many desert settlements along historic Route 66 came and went with little fanfare, Chambless emerged as a remarkable oasis in the early 1920s at the critical intersection of Cadiz Road and National Trails Road.

You’ll find its Chambless history began with a family-built store that expanded when National Trails Road was renamed Route 66, transforming this humble homestead into an essential waypoint. This desert stop was eventually developed by Fannie Gould into a true desert refuge featuring a rose garden and fish pond that delighted weary travelers. The buildings were constructed using adobe bricks for insulation against the extreme desert temperatures.

James and Fannie Chambless: Pioneers of the Mojave

You’ll find the remarkable story of James and Fannie Chambless woven deeply into the fabric of this Mojave Desert community, as they transformed harsh terrain into an essential waystation for weary travelers.

Their homestead, established in the early 1900s, evolved from a simple family dwelling into an important desert oasis that would serve countless Route 66 voyagers for decades.

The Chambless family’s entrepreneurial spirit and resilience not only created a sustainable life in challenging conditions but established a legacy that continues through the ghost town bearing their name. Today, genealogy enthusiasts can research the Chambless family history and connections using family history resources available through various websites.

Desert Oasis Creators

In the vast, unforgiving landscape of the Mojave Desert, James and Fannie Chambless carved out more than a homestead—they created a lifeline for weary travelers.

Their oasis creation transformed a harsh wilderness into an essential waypoint along the National Old Trails Road, later Route 66. You’d find water, gas, food, and rest at their establishment when nothing else existed for miles.

They built not just buildings, but a community gathering place where stranded motorists found help and locals connected despite the isolation. Much like how family history resources help connect people to their roots, the Chambless stop connected travelers to essential services in the barren desert landscape.

The couple adapted continuously to changing times, expanding from a simple water stop to a diversified business serving the evolving needs of cross-country drivers.

Their entrepreneurial spirit and resilience against drought, dust storms, and economic hardships embodied the pioneer ethos that shaped America’s western expansion.

Route 66 Legacy

The legacy of the Chambless settlement became inextricably linked with the most famous highway in American history. As Route 66 transformed from a dirt road into a paved artery of American mobility, the Chambless family adapted, moving their enterprise to meet the new alignment of the Mother Road.

You’ll find Chambless history deeply embedded in the 1946 “Guide Book to Highway 66,” where their establishment earned recognition as a rare “desert oasis.”

With its wide-porched gas station and café, travelers could escape the Mojave heat while refueling both vehicles and bodies. The shaded rest stop became essential infrastructure for the estimated two million soldiers who passed through during World War II training exercises.

This wartime traffic cemented Chambless’s place in Route 66 nostalgia as both a practical necessity and cultural touchstone. Originally named Cadiz station, the settlement followed the Atlantic and Pacific Railroad’s alphabetical naming convention before adopting the family name.

Today, the town has very low population, with most buildings standing as silent reminders of the once-bustling Route 66 era.

Life in a Railroad “Alphabet Town”

As you travel the Mojave Desert railroad corridor today, you’re witnessing the remnants of Lewis Kingman’s methodical alphabetical naming system that created Chambless as the “C” station in a strategic series extending from Amboy to Needles.

These railroad alphabet towns weren’t arbitrary settlements but calculated waypoints where steam locomotives could access critical water supplies in the harsh desert environment. Similar to how Amboy was named as part of the same railroad naming scheme in the late 1850s.

Chambless and its sister stations formed a lifeline across the Mojave‘s punishing terrain, their precise spacing and water access determining the very rhythm of desert rail travel before Route 66 diverted America’s transportation story to the highways. The area’s historic significance continues despite Route 66 closure in 2014 with no scheduled reopening due to budget constraints.

Water Stops Essential

Railroad operations across the Mojave Desert depended on three critical water stops known as “alphabet towns,” with Chambless serving as one of these essential outposts.

When you’re crossing harsh desert terrain with steam locomotives, water scarcity becomes your greatest challenge. At Chambless Station, the water tower wasn’t just infrastructure—it was survival for the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway. Alongside Amboy and Bagdad, Chambless was named as part of the alphabetical naming system used by the railroad to organize its desert water stops.

- Steam engines required frequent watering, especially in arid regions devoid of natural sources.

- Not all water worked—high mineral content damaged locomotive boilers.

- Tank cars transported suitable water from select springs when local sources proved too mineralized.

- Well maintenance demanded specialized equipment and expertise, repurposed from defunct mining operations.

These water stops transformed into natural hubs for settlement, creating commercial opportunities in the remote Mojave where the railroad’s need for water created civilization itself. This area sits above the Fenner Basin aquifer, an ancient underground water reservoir estimated to hold between 17 and 34 million acre-feet of water.

Named Alphabetical Settlements

Beyond their function as water stops, Chambless and similar outposts belonged to an ingenious organizational system that shaped Mojave Desert settlement patterns for generations.

The Atlantic and Pacific Railroad crafted an alphabetical naming convention across the Mojave, with Amboy, Cadiz, Danby, and Essex creating an easy-to-follow sequence for crews and travelers alike.

You’d find Chambless nestled among these railroad connections, part of a practical system designed to simplify navigation in the vast desert expanse.

Life in these alphabetical settlements revolved entirely around the railroad’s pulse. Your community would have centered on the station, with stores, post offices, and minimal services sprouting nearby.

The railway determined everything – when supplies arrived, when mail came, even who passed through your isolated desert home.

Railroad’s Desert Lifeline

Three essential structures dominated the skyline of Chambless during its railroad heyday: water towers that stood like sentinels against the Mojave’s harsh backdrop.

These towers weren’t just landmarks—they were lifelines for steam locomotives crossing the unforgiving desert terrain.

If you’d visited Chambless in its prime, you’d have witnessed:

- Water supply crews working tirelessly to maintain the precious resource

- Railroad employees and their families building a community around the rails

- Local businesses thriving on the steady stream of railroad traffic

- The daily rhythm of life synchronized with the train schedule

Your entire existence would have revolved around the railroad’s needs, your prosperity rising and falling with the fortunes of the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway that gave this alphabet town its purpose.

The Golden Age of Chambless Station (1930s-1960s)

The economic golden age of Chambless Station spanned four remarkable decades from the 1930s through the 1960s, coinciding perfectly with Route 66’s peak popularity as America’s premier transcontinental highway.

During this era, you’d find Chambless thriving as a desert oasis with its gas station, grocery, café, motel, and auto repair shop often backed up with customers waiting days for service.

The station’s covered porch became a cultural significance for weary travelers seeking relief from the Mojave heat.

Nearby historical landmarks like Roadrunner’s Retreat café symbolized Route 66’s unique traveler culture.

The town’s rose garden and fish pond transformed this harsh desert stop into a welcoming respite.

Military personnel from the Mojave Anti-Aircraft Range frequently visited, with Fannie Chambless offering her famous lemonade to soldiers passing through this essential desert lifeline.

Architecture and Adaptation to Desert Living

While travelers admired Chambless primarily as a welcome respite from their long desert journeys, the settlement’s architectural design revealed thoughtful adaptation to the harsh Mojave environment.

Desert architecture here wasn’t accidental but strategic, employing materials specifically chosen for climate adaptation.

- Adobe bricks formed the main buildings, providing exceptional insulation against extreme temperature fluctuations.

- Modern fireproof hollow tile construction guaranteed durability for the camp cottages.

- Wide porches and gabled roof canopies created critical shade zones for visitors and workers.

- The private well—unique between Needles and Newberry—supported luxuries like showers, a fish pond, and rose gardens.

You can still spot concrete structures standing defiantly against time, proof of Chambless’ pragmatic building approach that turned a harsh desert outpost into a functioning community.

The Famous Rose Garden and Fish Pond

In stark contrast to the surrounding Mojave Desert, you’d find Fannie Gould’s meticulously maintained rose garden and fish pond creating a genuine oasis at Chambless Camp.

These botanical features, established in the late 1930s, offered travelers respite from the harsh desert environment with unexpected splashes of color, fragrance, and the soothing sounds of water.

Fannie’s dedication to maintaining this desert paradise symbolized the hospitality that made Chambless stand out among Route 66 stops, even serving as a backdrop where she reportedly offered lemonade to soldiers during WWII desert training exercises.

Fannie’s Desert Oasis

During the harsh conditions of Mojave Desert life, Fannie Gould created an unexpected haven that would become legendary among Route 66 travelers.

As wife of James Albert Chambless, Fannie transformed their roadside business into a true oasis hospitality center in the late 1930s. Her vision went beyond mere commerce—she established a welcoming refuge where desert flora thrived against all odds.

What you’d find at Fannie’s Desert Oasis:

- A large covered porch providing essential shade for weary travelers

- A stunning rose garden that dramatically contrasted with the barren landscape

- A soothing fish pond—a remarkable aquatic feature in the Mojave

- Adobe buildings with superior insulation against extreme temperatures

This sanctuary not only served regular travelers but also refreshed countless soldiers training nearby during WWII.

Lush Amid Barren

Fannie Gould’s most remarkable achievement at Chambless Camp wasn’t simply establishing a business but creating what many travelers considered miraculous—a vibrant splash of color and life against the Mojave’s relentless beige palette.

Her rose garden and fish pond transformed a harsh desert corner into a celebrated oasis of tranquility.

You’d have marveled at her dedication to oasis sustainability, drawing precious water from the local well to nurture roses when most would’ve deemed such historical landscaping impossible.

The fish pond provided cooling respite while becoming a focal point for weary Route 66 travelers.

Featured in postcards and travel guides, Fannie’s lush creation became synonymous with Chambless itself.

Though the town now stands abandoned, the legacy of this desert oasis remains—a proof of ingenuity amid barrenness.

When Interstate 40 Changed Everything

The construction of Interstate 40, which officially opened in 1973, devastated the once-thriving desert oasis of Chambless almost overnight.

This interstate impact rerouted traffic several miles north, cutting off the steady flow of tourists and motorists that had been Chambless’ lifeblood for decades.

You can witness the ghost town transformation in the remnants that remain.

- Gas stations and cafés that once served weary travelers now stand abandoned

- The Roadrunner’s Retreat, once a recognizable landmark, closed shortly after I-40 opened

- Residents quickly departed to seek livelihoods elsewhere

- What was once an essential rest stop became merely a historical footnote

The high-speed interstate travel replaced the slower, local Route 66 experience, leaving Chambless and similar towns to slowly fade into the desert landscape.

What Remains Today: A Photographic Journey

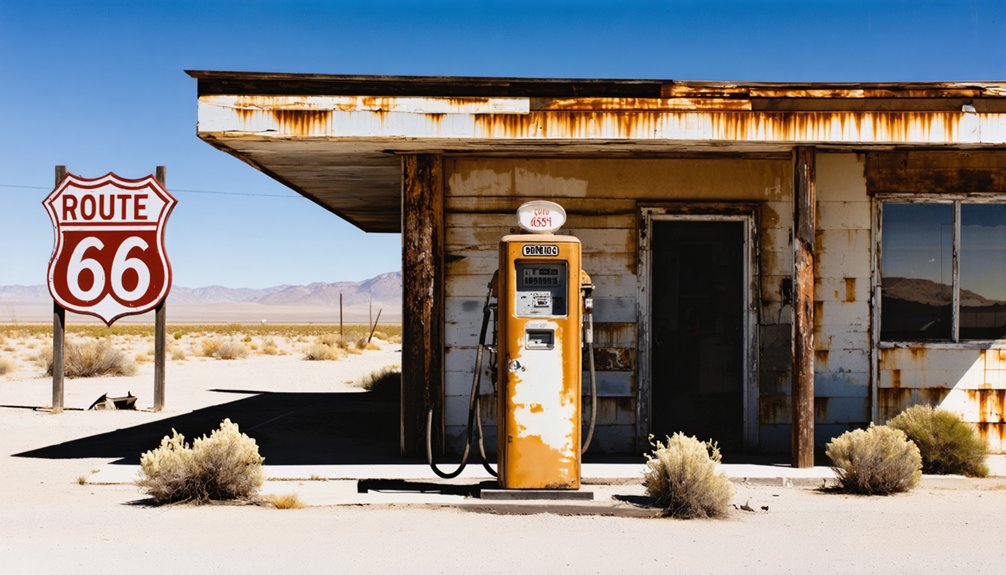

Standing like skeletal monuments to a bygone era, Chambless’ remaining structures offer a haunting photographic journey for Route 66 enthusiasts and urban explorers.

You’ll find the iconic Roadrunner Café and its towering sign among the most compelling subjects for ghost town photography, especially during golden hour when desert light casts long shadows across decaying porches.

Behind tall wired fences, tourist cabins and the gas station create stark compositions against the Mojave’s unforgiving landscape.

For best photographic techniques, bring wide-angle lenses to capture the relationship between ruins and the vast Bullion Mountains backdrop.

Consider bracketing your exposures—the harsh desert light creates challenging contrast between bright exteriors and shadowy interiors of these abandoned shells where tumbleweeds now gather, telling stories of abandonment after Interstate 40 diverted life elsewhere.

Preservation Efforts and Historical Recognition

Despite decades of abandonment, Chambless has witnessed remarkable preservation momentum in recent years, centered around the iconic 1962 Road Runner’s Retreat truck stop.

Owner Gus Lizalde, who purchased the property in 1990, leads this grassroots preservation effort with hands-on dedication and community involvement.

- National Park Service has awarded multiple Route 66 cost-share grants supporting sign restoration and building stabilization

- Plans include rehabilitating nine concrete cottages and adding a Route 66 shield-shaped swimming pool

- Vintage Airstream trailers will be refurbished for rental in the trailer park area

- The site qualifies for National Register of Historic Places listing

You’ll find this desert oasis increasingly featured in “Doors Open California” tours as restoration continues, with local enthusiasts and Route 66 aficionados rallying behind its revival.

Visiting Chambless: Tips for Route 66 Explorers

As preservation efforts shine new light on Chambless’s historical significance, adventurous travelers continue seeking this authentic slice of Route 66 nostalgia.

When planning your ghost town exploration, remember you’re visiting a remote desert outpost with no services—bring ample water, food, and fuel.

Navigate carefully to Chambless using its coordinates (34°33′41″N 115°32′41″W), located south of I-40 on the old highway alignment.

Check road conditions beforehand, as sections may be impassable due to flooding.

For ideal desert photography, arrive during golden hour when the ruins cast dramatic shadows.

Always respect private property and don’t enter deteriorating structures.

The nearby Roadrunner’s Retreat sign and remaining cabins offer compelling subjects against the Mojave landscape.

Frequently Asked Questions

Were Any Movies or TV Shows Filmed in Chambless?

No, this Route 66 ghost town hasn’t been documented as a filming location. You won’t find any movies or TV shows in Chambless’s film history, unlike nearby Mojave Desert locations.

What Happened to the Chambless Family After the Town Declined?

Frankly, family fates faded from formal records. You won’t find detailed accounts of the Chambless family’s whereabouts after the town’s decline. Their town legacy lives on primarily through Route 66 historical accounts.

Are There Any Dangerous Wildlife or Hazards Visitors Should Know About?

You’ll encounter Mojave Green rattlesnakes—extremely venomous and active April-September. Watch for abandoned mines, unstable buildings, and wildlife like coyotes. Practice wildlife safety by wearing boots and hiking precautions include carrying satellite communication.

Can Visitors Still See the Original Route 66 Pavement?

Yes, you’ll find original Route 66 pavement east of Cadiz where historic preservation allows for authentic visitor experiences. Segments near Chambless remain partly visible though some are overgrown or restricted by closures.

Are There Any Local Legends or Ghost Stories About Chambless?

Unlike 75% of Route 66 ghost towns, Chambless lacks documented ghostly sightings. You’ll find more atmosphere than haunted history here, with abandoned buildings creating their own eerie, spectral presence.

References

- https://digging-history.com/2014/01/22/off-the-map-ghost-towns-of-the-mother-road-chambless-california/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chambless

- https://www.exploratography.com/blog-66/chambless-cal-rt-66

- http://patricktillett.blogspot.com/2013/06/chambless-california-route-66-ghost-town.html

- http://route66times.com/ca/chambless.htm

- https://www.ghosttowns.com/states/ca/cadiz.html

- https://kids.kiddle.co/Chambless

- https://www.trailsendpublishing.com/blog/chambless-california

- http://cali49.com/mojave/2014/11/20/rt-66-chambless

- https://www.theroute-66.com/chambless.html