You’ll find Chant, Oklahoma nestled in the state’s mining region, where it emerged as a bustling coal town in the early 1900s after the Fort Smith and Western Railroad arrived in 1901. The San Bois Coal Company built 400 houses for miners, creating a thriving community with 15 active mining shafts. By the 1960s, economic decline and environmental contamination forced residents to abandon the town. The crumbling ruins and weathered grave markers hold fascinating tales of frontier life, industrial ambition, and ultimate decline.

Key Takeaways

- Chant became a ghost town after mining operations collapsed in the 1950s, causing population decline from 14,000 to 2,500 residents.

- The San Bois Coal Company built 400 houses in Chant and McCurtain, establishing a thriving mining community.

- Environmental contamination led to EPA Superfund designation in 1983, forcing remaining residents to evacuate due to health risks.

- Notable ruins include a roofless schoolhouse, crumbling post office, church ruins, and remnants of the general store.

- Federal buyout programs between 2000-2009 encouraged the last residents to relocate, completing Chant’s transformation into a ghost town.

The Birth of a Frontier Settlement

As the federal government designated most of present-day Oklahoma as Indian Territory in 1834, a complex web of forced tribal relocations and settler migrations would shape the region’s development.

You’ll find the pioneer struggles of early settlers manifested in their basic shelters and determined efforts to transform prairie into farmland, while nearby Native communities faced devastating displacement through events like the Trail of Tears.

Cultural exchanges emerged as missionaries established institutions like Dwight Mission among the Cherokee, though these interactions occurred against a backdrop of federal pressure and tribal displacement.

Along the growing railroad lines, you’d have witnessed towns springing up as settlers formed grassroots governments and school boards.

Their traditions from back East blended with frontier life, creating new community customs even as tribal nations fought to maintain their autonomy in an increasingly restricted territory.

The Cheyenne-Arapaho Reservation opened in 1892, bringing a wave of settlers seeking claims within its 3.5 million acres.

The Comanche and Kiowa peoples had already transformed the region’s culture after their early 18th century migration introduced horse-based practices to the Southern Plains.

Railroad Dreams and Economic Foundations

When the Fort Smith and Western Railroad reached McCurtain in 1901, it transformed Chant from a modest mining settlement into a bustling economic hub.

You’d have witnessed rapid railroad expansion as tracks stretched westward to the Canadian River, opening unprecedented opportunities for trade and mobility. Post-Civil War treaties had paved the way for this development by allowing railroads to cross through Indian territories.

The San Bois Coal Company seized this moment of economic integration, constructing 400 company houses for miners across Chant and McCurtain. The Irish-derived name McCurtain reflected the cultural heritage of many early settlers in the region.

Daily Life in Early Chant

In early Chant, you’d find residents gathering frequently around mine-related events and community functions, with churches and informal meetups serving as social anchors for the town’s 3,000-plus inhabitants.

Your daily work life would’ve centered on the 15 active mining shafts or the supporting businesses, including grocery stores and shops that kept the coal-focused economy running. Similar to the Sacred Heart Mission, the local church played a vital role in education and community development. Like many Oklahoma towns during this era, Chant’s ultimate decline was due to resource exhaustion.

You’d have lived in one of the modest homes built strategically near the mine entrances, where families maintained close-knit relationships with neighbors while dealing with the constant pressures of mining life.

Community Gatherings and Events

Through various social and recreational gatherings, early Chant residents maintained strong community bonds despite the challenging frontier conditions.

You’d find community celebrations centered around the local schoolhouse, which served as a hub for both educational and social activities. Similar to towns in No Man’s Land, residents learned to create their own entertainment without formal authority structures. Like many Oklahoma frontier towns, Chant’s residents gathered regularly for religious services, civic meetings, and seasonal festivals that marked important agricultural milestones.

The Main East-West Road allowed residents to travel more easily to town events and gatherings.

The town’s social fabric was strengthened through harvest celebrations and community dances, where families would come together to share news and entertainment.

Churches played an essential role in organizing events, while seasonal markets provided opportunities for residents to trade goods and socialize.

These gatherings helped sustain Chant’s sense of unity during its early years, offering much-needed respite from the demanding pioneer lifestyle.

Work and Trade Activities

Daily life in early Chant revolved around a diverse mix of agricultural and commercial activities that sustained the community’s economy.

You’d find local craftsmanship thriving in the town’s blacksmith shops, where skilled workers repaired farming tools and shod horses. Like many mining towns that employed over 11,000 workers during peak operations, the trade dynamics centered on small family farms, with residents sharing labor during planting and harvest seasons. Similar to Clearview’s success, the town featured five grocery stores that served the local population.

If you’d visited Chant between 1890 and 1910, you’d have seen grocery stores and boutiques offering essential goods, while farmers bartered their produce in the local market.

The town’s economic significance also drew influence from nearby oil boom settlements, creating opportunities for residents to commute by rail to mining and industrial centers.

However, this delicate economic balance couldn’t withstand the pressures of industrialization and the Great Depression.

Family Home Structures

While frontier architecture dominated early Chant’s residential landscape, the town’s family homes revealed distinct social hierarchies through their construction materials and designs.

You’d find most residents living in wooden-frame houses with simple gabled roofs and welcoming front porches, while wealthier families showcased their status through brick construction and decorative stone columns.

Typical family layouts featured central living spaces and kitchens, often separated from the main structure to prevent fires.

You’d spot various outbuildings behind these homes – from servants’ quarters and barns to smokehouses and root cellars.

The architectural features reflected practical needs: multifunctional rooms served both daily activities and social gatherings, while storage spaces preserved food through seasons.

Wood-burning stoves provided heat, and kerosene lamps lit the spaces before electricity arrived.

The Decline Years: What Went Wrong

You’ll find that Chant’s decline began when Route 66 traffic diminished after the new interstate system drew travelers away in the late 1950s.

The economic ripple effects hit hard and fast – gas stations closed first, followed by motels and restaurants, triggering a chain reaction of business failures throughout the early 1960s.

Within a decade, Chant’s population had dropped by over 80% as families left to seek opportunities in larger cities, leaving behind empty buildings and crumbling infrastructure.

Economic Ripple Effects

As the late 19th century ushered in America’s industrial revolution, Chant and similar Oklahoma farming communities struggled to adapt from their agrarian roots.

The economic impact rippled through every aspect of daily life as agricultural mechanization reduced available jobs and market demands shifted away from local products. You’d have seen the community’s resilience tested when local businesses – from grocery stores to blacksmith shops – began closing their doors.

The domino effect was devastating. As employment opportunities vanished, younger residents moved away, leaving an aging population behind.

Local tax revenues plummeted, leading to reduced municipal services. With each closure of a church, school, or store, the social fabric of Chant unraveled further, making it increasingly difficult to attract new residents or retain existing ones.

Population Exodus Timeline

Three distinct phases marked Chant’s population exodus, beginning with the mining industry’s collapse in the 1950s.

You’d have witnessed the first wave of departures as mining employment plummeted from 11,000 to 4,000 workers, triggering a sharp population decline from 14,000 to 2,500 residents by 1960.

The second phase intensified in 1983 when the EPA designated the area a Superfund site due to toxic contamination.

Environmental hazards forced another exodus through the 1990s as health risks became undeniable.

The final phase occurred between 2000-2009, when federal buyout programs convinced most remaining residents to relocate.

Notable Buildings and Landmarks

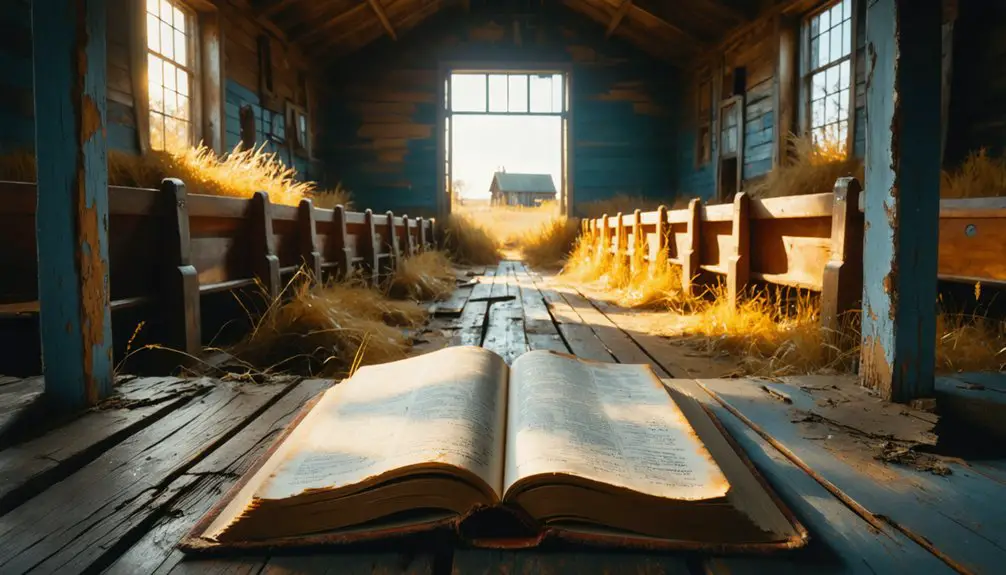

Time-worn remnants of Chant’s past dot the Oklahoma landscape, offering glimpses into this once-thriving settlement.

You’ll find the abandoned structures scattered throughout the area, including a roofless schoolhouse, crumbling post office, and church ruins that once served as community anchors. The general store’s partial walls still stand as evidence to its historical significance as a local trading hub.

Near the town center, you’ll spot foundations of industrial buildings and traces of the old rail siding that connected Chant to neighboring communities.

The surrounding area features weathered grave markers in an overgrown cemetery, while native vegetation steadily reclaims former residential sites marked by collapsed log cabins.

Remnant fences and boundary markers still define the ghostly outlines of what was once a bustling frontier town.

Local Stories and Legends

You’ll find Chant’s history preserved through the vivid oral traditions passed down by locals, who tell tales of outlaws meeting at the town’s saloons and mysterious happenings near the old store sites.

The community’s social fabric included unique gatherings like moonlit cemetery parties, which have become part of the area’s ghostly narrative alongside stories of the Doolin-Dalton Gang‘s activities.

Local folklore paints a picture of both everyday life and extraordinary events, from Native American spiritual encounters to accounts of unexplained phenomena that continue to intrigue visitors to this abandoned settlement.

Oral Traditions and Tales

While the physical remains of Chant have largely disappeared, the town’s spirit lives on through a rich tapestry of oral traditions and local legends.

Through oral folklore, you’ll hear tales of a once-thriving railroad town that fell victim to shifting transportation routes in the early 1900s.

Local ghost stories tell of mysterious figures in period clothing wandering along abandoned tracks, unexplained footsteps echoing through empty lots, and a protective spirit that guards the town’s ruins from vandals.

You’ll discover accounts of a defiant merchant who refused to leave, a vanished family whose story haunts an abandoned house, and whispered tales of hidden treasures left behind by fleeing residents.

These stories preserve the memory of Chant’s pioneer spirit and sudden decline.

Community Events Remembered

Settlers of Chant kept their memories alive through vibrant community events that brought together families and neighbors to celebrate their shared heritage.

You’ll find echoes of these gatherings in the seasonal festivals that featured historical reenactments, where locals portrayed the daily life and significant moments of their ancestors.

Community picnics served as central meeting points, often coinciding with anniversaries of notable town events.

During autumn gatherings, you’d experience nighttime storytelling sessions that brought the town’s past to life.

Local historical societies organized regular lectures where elders shared firsthand accounts of Chant’s glory days.

These events weren’t just celebrations – they were essential links connecting generations, preserving the authentic spirit of Oklahoma’s frontier heritage through shared experiences and collective memory.

Ghost Town Folk Heroes

Legendary figures emerged from Chant’s frontier days, weaving a rich tapestry of local folklore that defined the town’s character.

You’ll find tales of outlaw legends who challenged authority and railroad heroes who shaped the community’s growth during its peak years. The town’s storytelling tradition preserves the memory of those who influenced its development and eventual decline.

- Local roughnecks and wildcatters who risked everything in search of oil fortunes

- Native American leaders who negotiated the changing landscape as settlers arrived

- Saloon owners who wielded significant economic power before statehood regulations

- Railroad workers and entrepreneurs who brought temporary prosperity through new transportation routes

These characters reflect the complex interplay of law and lawlessness, innovation and tradition that characterized Oklahoma’s frontier communities like Chant.

Archaeological Findings and Remnants

Extensive archaeological excavations conducted by the Oklahoma Historical Society in the 1

Environmental Impact on Settlement Patterns

The devastating environmental legacy of lead and zinc mining operations fundamentally shaped settlement patterns in Chant, forcing a complete exodus of residents due to severe contamination. The toxic legacy of mining created an environmental migration crisis that you can still witness today in the abandoned landscape.

- Lead and zinc-laden chat piles, stretching miles high, poisoned the soil and groundwater, making residential areas uninhabitable.

- Structural instability from underground mining created dangerous sinkholes, threatening building foundations.

- Contaminated water from 14,000 flooded mine shafts polluted drinking sources and waterways.

- High blood lead levels, especially in children, ultimately drove government-mandated evacuations and buyouts, leading to the town’s complete abandonment.

These environmental hazards transformed a once-thriving community into an uninhabitable zone requiring decades of remediation.

Photographic History Through Time

While the environmental devastation left physical scars on Chant’s landscape, photographic records tell an equally compelling story of the town’s rise and fall.

You’ll find early 1900s images capturing Chant’s significance through photographic techniques that documented rows of miners’ homes, bustling business districts, and the coal mining infrastructure that defined daily life.

The 1912 Mine Number Two disaster marks a pivotal shift in this visual narrative.

Historical preservation efforts have maintained poignant photographs of rescue attempts, mourning families, and the seventy-three graves at Miners Cemetery.

Later images from the 1940s-1960s chronicle Chant’s decline through shots of abandoned railroads, flooded mine shafts, and empty buildings.

Today’s photographs focus primarily on memorial sites, serving as silent witnesses to the ghost town’s mining heritage.

Legacy in Oklahoma’s Ghost Town Heritage

Mining disasters, economic busts, and shifting demographics have shaped Oklahoma’s rich tapestry of ghost towns, with Chant representing just one chapter in this complex historical narrative.

The cultural resilience and historical significance of these abandoned communities reflect broader patterns in the state’s development, from boom-to-bust resource extraction to the unique stories of all-Black towns that once thrived.

- Oklahoma’s ghost towns often emerged from single-industry economies that couldn’t sustain themselves once resources depleted or markets shifted.

- All-Black communities demonstrated remarkable self-determination during segregation, establishing vibrant commercial and social institutions.

- Outlaw history became permanently woven into certain towns’ identities, creating lasting cultural legacies.

- Environmental consequences, particularly in mining communities, led to permanent abandonment and federal intervention.

Frequently Asked Questions

Are There Any Documented Paranormal Activities or Ghost Sightings in Chant?

You won’t find any verified ghostly encounters or haunted locations in historical records or paranormal databases. No documented evidence exists of supernatural activity, though unofficial local stories might circulate privately.

What Native American Tribes Originally Inhabited the Land Where Chant Was Built?

While you might picture empty plains, the tribal history reveals Caddo, Wichita, and Spiro Mound Builders first inhabited this land, with their rich cultural heritage spanning from 500 to 1300 A.D.

Did Any Famous Outlaws or Historical Figures Ever Pass Through Chant?

You won’t find any documented outlaw history or famous visitors in Chant’s records. Based on available historical evidence, there’s no proof that any well-known outlaws or significant figures passed through this small community.

Can Visitors Legally Explore the Chant Site Today?

You’ll need explicit permission to visit due to legal restrictions, as most ghost towns are private property. Check with local authorities and follow visitor guidelines to guarantee lawful exploration.

Were There Any Significant Natural Disasters That Contributed to Chant’s Abandonment?

Like footprints in shifting sand, you won’t find evidence of flood damage or drought impact causing Chant’s decline. Historical records don’t show any natural disasters contributing to its abandonment.

References

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_ghost_towns_in_Oklahoma

- https://www.visitstillwater.org/things-to-do/stillwater-area-history/the-doolin-dalton-gang-and-the-legacy-of-the-battle-of-ingalls/

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-jYN1_E2VV0

- https://www.kosu.org/local-news/2014-05-23/ghost-towns-all-black-oklahoma-towns

- https://www.okhistory.org/publications/enc/entry?entry=GH002

- https://www.okhistory.org/publications/enc/entry?entry=SE024

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_Oklahoma

- https://www.oml.org/municipal-messenger/2020/12/17/christmas-on-the-frontier-indian-territory

- https://www.worldatlas.com/articles/when-was-the-frontier-closed.html

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Land_Rush_of_1889