You’ll find Columbus ghost town near Columbus Salt Marsh in Esmeralda County, Nevada, where a once-thriving 1,000-resident mining community operated from 1865 to the 1880s. The town boomed after the 1871 borax discovery, developing 28 stamp mills, a newspaper, and stores. Today, you can explore building foundations and mining tank remnants that tell the story of Nevada’s industrial past. The site’s rich history holds fascinating details about life in this frontier boomtown.

Key Takeaways

- Founded in 1865 near Columbus Salt Marsh, Nevada, the town grew rapidly due to borax mining and reached 1,000 residents by 1875.

- The Pacific Borax Company’s relocation triggered Columbus’s decline, with population dropping to 100 residents by 1881.

- The town featured 28 stamp mills, borax factories, a newspaper, stores, and an iron foundry during its peak mining years.

- Ray, the last resident, lived in Columbus until 2009, serving as unofficial caretaker and historian of the ghost town.

- Visitors can explore building foundations and mining remnants near U.S. Highway 95, with state agencies protecting the site’s historic value.

A Mining Town’s Birth in 1865

When American settlers established Columbus in 1865, they strategically positioned the mining town near Columbus Salt Marsh in Nevada’s Esmeralda County.

These pioneering prospectors knew the site’s value – it was the only location with enough water to support essential mining techniques for processing precious metals.

You’ll find that the early settlers’ first major development centered on a relocated quartz mill from Aurora, marking the town’s industrial beginnings.

Within just one year, about 200 hardy souls called Columbus home, drawn by the promise of mineral wealth and the town’s position on the edge of the alkali flats.

The site’s natural advantages perfectly suited the settlers’ needs, offering both the water resources for milling operations and the freedom to establish their own bustling frontier community.

The discovery of borax in 1871 transformed the town’s economy and attracted four major mining companies to the area.

The town quickly developed a robust infrastructure with stores and foundries, serving the needs of its growing mining community.

The Great Borax Discovery

Within two years, you’d have witnessed four companies launching borax extraction operations, with Pacific Borax Company leading the charge.

The borax rush took hold swiftly, as four rival companies raced to establish mining operations in this mineral-rich frontier.

They installed advanced mining technology for that era, running round-the-clock shifts and operating 28 stamps across three processing mills.

By 1875, the town was bustling with 1,000 residents, boasting its own newspaper (The Borax Miner), stores, a post office, and even an iron foundry.

The discovery sparked a brief but intense boom that would define Columbus’s glory days.

The town’s residents could enjoy entertainment from the Columbus Jockey Club, which organized regular horse racing events.

The 130-mile wagon road from Wadsworth provided crucial transportation of mining equipment and supplies to support the booming operations.

Life During the Boom Years

Life in Columbus during its heyday painted a vibrant picture of Western ambition and industry. You’d find yourself amid a bustling community of 1,000 residents, where the sounds of 28 stamp mills crushing ore echoed through the desert air.

The town’s mining legacy thrived as workers toiled day and night in the borax factories for eight-month stretches. The discovery of salt in 1871 brought even more prosperity and development to the growing community. Pacific Borax Company established major operations that dominated local industry.

Despite the harsh environment, you’d discover a strong community identity fostered by *The Borax Miner* newspaper and the local post office. Children attended the adobe schoolhouse while their parents worked the mines or operated supporting businesses like the iron foundry.

The Columbus Jockey Club‘s racetrack offered entertainment, proving that even in this remote outpost, residents carved out spaces for leisure amid their industrious pursuits.

Economic Growth and Development

When you visit Columbus today, you’ll find remnants of its economic engine – the mills that processed gold, silver, and borax from nearby mines starting in 1865.

You can trace the town’s growth through the $15,000 wagon road that connected Columbus to Carson’s railroad freight lines, though this transportation link faced stiff competition from the Wadsworth route. Like the Pioneer Saloon in Goodsprings, the local businesses captured both mining activity and community life.

As mining declined in the 1880s, local entrepreneurs attempted to diversify with ventures like a soap factory and the Columbus Jockey Club’s racetrack, but these efforts couldn’t sustain the town’s economy. In 1918, the Warner Mining Company initiated new operations, constructing a cyanide plant and concentration facility connected by a 1500-foot tramway.

Mining and Mill Operations

As Columbus emerged in 1865, the establishment of a strategically placed quartz mill marked the beginning of significant mining operations in the area.

You’ll find that early mining technologies focused on extracting silver from the Candelaria Hills and salt from the Columbus salt marsh. The relocation of a stamp mill from Aurora enhanced the town’s processing capabilities.

When borax was discovered in 1871, mill operations expanded dramatically. The population grew rapidly and reached peak residents of approximately 1,000 by 1875.

You can trace the peak of industrial activity to 1873-1875, when three mills with 28 stamps operated continuously for eight months each year. The Pacific Borax Company emerged as the dominant force, leading multiple companies that extracted and processed the valuable mineral.

These operations demanded massive quantities of salt for ore processing, creating a symbiotic relationship between the town’s different mining ventures. The district proved highly lucrative, generating over $20 million in silver ore production during the 1870-1880 period.

Transportation Network Development

Through primitive dirt roads and rugged trails, Columbus’s early transportation network served the crucial needs of its burgeoning mining operations.

You’d have seen ox carts and horse-drawn wagons laboriously hauling ore and supplies across the rugged terrain, battling seasonal weather that often delayed shipments.

The arrival of rail connectivity transformed Columbus’s economic prospects.

The new transportation infrastructure allowed mines to ship larger quantities of ore to distant markets while bringing in essential equipment and supplies.

You can still trace where the freight lines once ran, enabling the town to thrive beyond its immediate surroundings.

Later paved roads replaced the old dirt paths, reducing costs and connecting Columbus to Nevada’s expanding highway system.

These improvements helped sustain the town’s commerce even as mining activity declined.

Local Business Diversification

Despite Columbus’s initial success as a mining town, local business leaders recognized the need to diversify beyond mineral extraction in the 1870s. Their business strategies included establishing an iron foundry, stamp mills, and ore processing plants to support the mining operations.

You’ll find evidence of their economic resilience in ventures like the soap factory built in 1881 and entertainment initiatives by the Columbus Jockey Club.

However, these diversification efforts couldn’t prevent the town’s decline when the Pacific Borax Company relocated in 1875. The exodus triggered a domino effect, causing freight services, newspapers, and retail stores to shut down.

Daily Life in a Bustling Mining Community

You’ll find traces of a vibrant social scene at Columbus’s horse racing track, where the local Jockey Club once drew crowds to their grandstand on the alkali flat.

The town’s weekly newspaper, *The Borax Miner*, kept residents connected to local happenings and mining developments during the community’s peak years.

As you explore the ruins near Columbus Salt Marsh today, you can imagine how the tight-knit population of 1,000 gathered for social events that helped them cope with their remote, harsh surroundings.

Mining Life and Culture

While silver and gold initially drew prospectors to Columbus in 1865, the town quickly evolved into a vibrant community of several hundred residents by the early 1870s.

You’d find miners and mill workers laboring through demanding eight-month shifts, while freight teams coordinated daily shipments of ore across 125-mile stretches to distant rail depots.

The workforce dynamics shaped daily life, with the community gathering at the iron foundry, local stores, and post office.

After long workdays, you could catch exciting horse races at the Columbus Jockey Club’s track or read the latest news in The Borax Miner.

The presence of an adobe schoolhouse showed this wasn’t just a town of transient workers – families put down roots here, creating a close-knit mining society that thrived until operations declined in the 1880s.

Community Gathering Places

As the town’s population grew in the 1870s, Columbus developed several essential gathering spaces that anchored daily social life.

You’d find community interactions centered around the bustling general store, where miners and families gathered to trade goods and share news. The schoolhouse served dual purposes, hosting both education and community meetings, while the post office became a daily hub for residents collecting mail and exchanging updates.

Social cohesion flourished through informal gatherings at these civic spaces. Though the town lacked formal entertainment venues, you’d witness impromptu meetings along the main street, where the iron foundry’s rhythmic sounds provided a constant backdrop.

The cemetery, though solemn, brought townsfolk together during burials, reinforcing their shared bonds in this remote mining community.

Entertainment and Recreation

Despite the demanding nature of mining life, Columbus residents found diverse ways to entertain themselves through organized events and informal gatherings.

You’d find excitement at the Columbus Jockey Club’s racetrack, where locals bet on horses and socialized at the grandstand. The town’s saloons served as vibrant hubs for local entertainment, hosting card games, music, and storytelling late into the night.

The weekly Borax Miner newspaper kept you informed about upcoming social gatherings and cultural events. You could catch traveling performers at makeshift venues, enjoy boxing matches, or participate in shooting contests.

The adobe schoolhouse doubled as a community center for dances and holiday celebrations. Whether you sought thrills at the gambling tables or preferred casual gatherings with fellow miners, Columbus offered entertainment options for every taste.

From Prosperity to Decline

When Columbus reached its peak in 1875 with nearly 1,000 residents, few could’ve predicted its rapid decline. The town’s economic challenges began when the Pacific Borax Company moved operations 30 miles south, triggering a chain reaction that would transform this bustling mining hub into a ghost town.

- Mining techniques couldn’t sustain profitability as ore quality diminished

- Population plummeted to just 100 residents by 1881

- Local businesses struggled as key mining operations relocated

- A soap factory and horse racing track tried to diversify the economy

- By the mid-1880s, mining and milling operations had completely ceased

You’ll find that despite efforts to keep the town alive, Columbus couldn’t overcome these setbacks.

The post office’s closure in 1899 marked the final chapter of this once-prosperous mining community, though remnants of its industrial past still stand as evidence to its legacy.

The Last Residents of Columbus

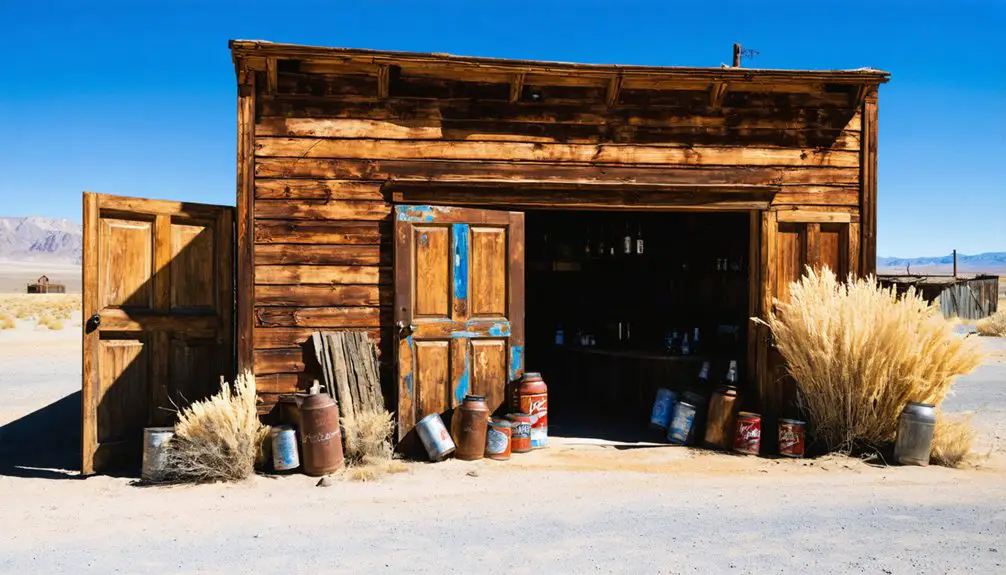

You’ll find traces of Ray’s solitary life in the old general store and his self-built garage, where this war veteran chose to live away from civilization until his death in 2009.

The site marks the end of Columbus’s human habitation, as Ray maintained the historic building while embracing the isolated desert environment.

His departure officially transformed Columbus into a complete ghost town, closing the final chapter of residency that had dwindled since the town’s mining heyday in the 1870s.

Wartime Veteran Ray’s Story

Among the final inhabitants of Columbus, Nevada, wartime veteran Ray emerged as a crucial figure in preserving the ghost town’s legacy during the late 20th century. His veteran’s resilience shone through as he maintained the town’s remaining structures until 1987, protecting essential pieces of Nevada’s mining history.

- Served as the town’s unofficial caretaker and historian

- Preserved the school and bowling alley against desert decay

- Provided firsthand accounts to visitors and researchers

- Adapted to life near Columbus Salt Marsh’s harsh conditions

- Maintained minor economic activity through tourism interest

Ray’s legacy lives on through his dedication to Columbus’s heritage.

You’ll find his story woven into the fabric of regional archives, highlighting how one determined resident helped bridge the gap between a living community and a historical landmark worth exploring.

Life After Mining Ended

Long before Ray’s time as caretaker, Columbus experienced a dramatic shift following the closure of its borax mining operations in 1881.

You’ll find that once-bustling streets quickly emptied as the population plummeted to roughly 100 residents, leaving behind crumbling adobe structures and an increasingly quiet landscape.

Those who stayed faced mounting economic hardships as alternate industries failed to materialize. While the post office remained operational until 1899, providing a lifeline to the outside world, community isolation grew more severe.

You can imagine the challenges of the final inhabitants who clung to their homes amid the ruins, organizing occasional horse races to maintain some semblance of social life.

Solo Living Until 2009

Despite the official abandonment of Columbus in 1899, several solitary individuals continued to inhabit this remote desert settlement well into the 21st century.

These last residents demonstrated remarkable self-sufficiency skills while facing significant isolation challenges in a town without basic services or infrastructure.

- Living without postal service, utilities, or local businesses

- Relying on distant towns for supplies and emergency assistance

- Maintaining historic structures amid harsh desert conditions

- Adapting to extreme environmental challenges alone

- Serving as unofficial caretakers of the site’s heritage

You’ll find their legacy in the preserved structures and carefully maintained artifacts that tell the story of frontier resilience.

These solo inhabitants bridged the gap between Columbus’s mining heyday and its modern status as a ghost town, contributing valuable insights into Nevada’s settlement patterns and cultural heritage.

Exploring the Ghost Town Today

While Columbus ghost town sits quietly in Esmeralda County today, its remote location offers determined explorers a genuine glimpse into Nevada’s mining past.

In addition to the charm of Columbus ghost town, exploring Colorado city’s history reveals rich stories and vibrant tales of pioneers who shaped the region. Visitors can uncover fascinating details about the early settlers and the unique challenges they faced in this rugged landscape. Each artifact and structure left behind serves as a testament to the city’s resilient spirit and enduring legacy.

You’ll find the site about five miles southwest of U.S. Highway 95, near the distinctive Columbus Salt Marsh. During your ghost town exploration, you’ll discover foundations of original buildings and remnants of mining tanks that tell the story of both 19th-century operations and 1950s cyanide processing.

You’ll need to prepare for extreme desert conditions and bring everything you need – there aren’t any amenities nearby.

As you navigate the archaeological remains, you’ll see Nevada Historical Marker No. 20, though it takes some searching to locate. The site’s isolation has helped preserve these fragments of history, letting you experience Nevada’s boom-and-bust mining era firsthand.

Preserving Nevada’s Mining Heritage

As Nevada’s mining heritage faces ongoing preservation challenges, state and federal agencies have implemented extensive protection measures for over 14,300 abandoned sites since 1987.

Mining archaeology reveals the rich cultural tapestry through artifacts and structures that tell the story of Nevada’s pioneering spirit.

- Stone tools and ceramics showcase prehistoric human activity

- Historic mining camps and shafts document industrial development

- Archaeological surveys guide heritage preservation efforts

- Environmental monitoring guarantees site stability

- Collaborative programs between federal, state, and tribal organizations protect cultural resources

You’ll find the Nevada State Historic Preservation Office actively working to protect these treasures while the Department of Minerals secures abandoned mines.

Through careful balance of environmental protection and historical conservation, you’re able to explore these remnants of Nevada’s mining past while guaranteeing their survival for future generations.

Columbus Salt Marsh Legacy

The Columbus Salt Marsh stands as a remarkable symbol of Nevada’s industrial and ecological heritage. You’ll find this unique closed basin maintaining a delicate balance between salt extraction operations and essential salt marsh ecology.

Modern environmental safeguards, including bird netting over saline ponds and sophisticated water management systems, protect the marsh’s diverse wildlife while industrial activities continue.

Careful engineering protects wildlife at Columbus Salt Marsh, where nets and water systems balance industrial needs with environmental preservation.

The site’s industrial impact is carefully monitored through thorough water quality testing and strict environmental controls. You can trace the marsh’s evolution from its mining origins to today’s regulated facility, where two-foot freeboards prevent pond overflow and v-ditches direct storm runoff.

Like other salt marshes worldwide, Columbus serves as a carbon sink and wildlife haven, though its inland location offers a distinctive glimpse into how industry and nature can coexist in Nevada’s arid landscape.

Frequently Asked Questions

What Happened to the Original Stamp Mill Equipment From Aurora?

You won’t find the original stamp mill equipment in Aurora today – it was dismantled, sold off, and scattered after operations ended. No equipment restoration efforts preserved these historic processing tools.

Were There Any Major Accidents or Disasters During Columbus’s Mining Operations?

While many Nevada mines suffered tragic disasters, you won’t find major mining accidents or disaster reports from Columbus’s operations. The site appears to have been spared catastrophic events during its active years.

How Did Residents Get Fresh Water in This Desert Settlement?

You’d find desert survival challenging as water sourcing relied on limited fresh water pockets near town, while most nearby water was brackish or saline, useful for mining but not drinking.

What Native American Tribes Lived in the Area Before Columbus’s Establishment?

Like shadows across desert sands, the Walker River and Yerington Paiute tribes called this land home. You’ll find their Native Tribes’ Cultural Heritage reflected in the region’s hunting and gathering traditions.

Did Any Famous People or Notorious Outlaws Ever Visit Columbus?

You won’t find records of famous visitors or notorious outlaws in Columbus’s history. While “Borax” Smith discovered minerals nearby, there’s no evidence he or other well-known figures visited the town.

References

- http://www.nv-landmarks.com/towns-c/columbus.htm

- https://www.destination4x4.com/columbus-nevada-state-historic-marker-20/

- https://kids.kiddle.co/Columbus

- https://www.nvexpeditions.com/esmeralda/columbus.php

- https://westernmininghistory.com/towns/nevada/columbus/

- https://noehill.com/nv_esmeralda/nev0020.asp

- https://www.hmdb.org/m.asp?m=240321

- https://shpo.nv.gov/nevadas-historical-markers/historical-markers/columbus

- http://www.onv-dev.duffion.com/articles/wadsworth-and-columbus-freight-road

- https://www.nvexpeditions.com/nye/washington.php