You’ll find Cuprum, Idaho nestled at 4,298 feet elevation, where nine year-round residents now call this former copper mining boomtown home. In the late 1890s, the town bustled with miners earning $18 daily, extracting high-grade copper alongside gold and silver deposits. Despite producing $1.2 million in early ventures, mining operations struggled with harsh terrain and high costs. Today’s well-preserved structures and scattered summer cabins tell a deeper story of boom, bust, and survival.

Key Takeaways

- Cuprum, Idaho is a former copper mining town established in 1893 that now exists as a ghost town with nine year-round residents.

- Located at 4,298 feet elevation, Cuprum features well-maintained structures and summer cabins, distinguishing it from typical deteriorating ghost towns.

- The town’s mining operations produced $1,200,000 in early ventures but struggled with high costs before finally closing in 2006.

- Visitors can explore the area independently during warmer months, though no formal tourist facilities or guided tours exist.

- The town’s history spans copper, gold, and silver mining, with peak activity during 1897-1898 when miners earned $18 daily.

The Birth of a Copper Mining Dream

While precious metals beckoned fortune-seekers to many Western territories, Cuprum’s mining story didn’t begin until 1893 when prospectors discovered rich copper deposits in this rugged corner of Idaho.

You can trace the town’s mining heritage to December 1, 1897, when the establishment of a post office signaled growing excitement about the area’s potential.

The copper boom that followed brought waves of determined miners who faced harsh terrain and intimidating challenges.

Rugged mountains and treacherous conditions tested the resolve of countless miners drawn to Cuprum’s copper-rich wilderness.

Despite their efforts and an estimated production of $1,200,000 from the district, these early ventures operated at considerable losses.

Yet the pioneering spirit prevailed, leading to significant mining developments that would shape Cuprum’s destiny.

The region became known for its exceptionally high grade copper deposits, which attracted continued mining interest alongside valuable gold and silver resources.

Today, at an elevation of 4276 feet, the town’s pristine buildings stand as testament to its mining legacy.

Life in Early Cuprum

As prospectors and their families flooded into Cuprum during its 1897-1898 peak, the once-quiet mountainside transformed into a bustling mining community.

You’d have found the community dynamics revolving around the mining operations, with daily routines shaped by the harsh mountain climate and demanding work schedules.

Life wasn’t easy – you’d need to brave the cold winters, navigate snow-covered two-wheel drive roads, and deal with the constant risks of mining accidents. Miners could earn wages of $18 per day during this period of Idaho’s mining history.

The town’s hospital stood ready to treat injured miners, while A.O. Huntley’s nearby ranch served as an essential waystation. The town’s name itself reflected its purpose, derived from the Latin word Cuprum, meaning copper.

The local post office kept you connected to the outside world, while the promise of a new smelter in 1898 brought hope for prosperity.

At day’s end, you’d return to your cabin, where social life centered around fellow mining families.

Mining Operations and Technical Challenges

You’d find Cuprum’s early mining operations primarily focused on underground extraction until 1974, when the Copper Cliff Mine changed to open-pit methods.

The mine maintained a high silver content in its ore, averaging 20 ounces per ton alongside copper deposits.

While the mine showed promise with its 409 short tons of copper production valued at $630,000 in 1974, you’ll notice the persistent struggle with profitability due to the challenging Kleinschmidt grade and high operational costs.

In 1960, the mining operations yielded 400,000 dollars worth of copper, but the extraction costs ballooned to $1.6 million, highlighting the economic challenges faced by the industry.

Despite technological advances and a flotation mill expansion to process 800 tons per day, you can trace how these mining ventures ultimately succumbed to economic pressures by the early 1980s, leading to the mine’s complete closure and demolition by 2006.

Copper Extraction Methods

In the rugged mines of Cuprum, copper extraction demanded sophisticated engineering and steadfast determination.

You’d find miners employing both open-pit and underground mining techniques, depending on the ore body’s location. The extracted ore underwent a meticulous process of grinding into fine powder before entering the concentration phase through froth flotation.

The concentrated ore then faced the intense heat of roasting and smelting, where sulfides transformed into oxides. Chilean mining experts were often consulted due to their extensive experience with similar extraction processes.

You’d witness the converting stage removing stubborn impurities to produce blister copper, followed by electrolytic refining to achieve nearly pure copper.

When dealing with oxide ores, the mining technology shifted to leaching and solvent extraction methods. Advanced water recycling systems helped minimize environmental impact while maintaining efficient production.

This systematic approach, though challenging, guaranteed the valuable metal’s successful extraction from Cuprum’s mineral-rich earth.

Profit-Loss Mining Cycles

The challenging copper extraction methods at Cuprum directly impacted the mine’s profit-loss cycles throughout its operational years.

You’d have witnessed stark contrasts in economic sustainability, from profitable periods like 1974’s production of 409 short tons of copper valued at $630,000, to devastating losses such as 1960’s $1.2 million deficit despite significant extraction.

Similar to the silver price collapse of 1888 that devastated many Idaho mining operations, Cuprum faced its own economic vulnerabilities that threatened its sustainability.

The struggle for operational efficiency was constant as you navigated the treacherous Kleinschmidt grade and attempted to shift from underground to open-pit mining.

While the mine’s potential showed promise with expanded reserves of over 2 million tons by 1973, the technical challenges of the Seven Devils region proved relentless.

Even with attempts to increase daily production from 300 to 800 tons, you couldn’t overcome the persistent hurdles that ultimately led to closure in 2006.

Transportation Struggles and Infrastructure

While Cuprum’s rich copper deposits held promise, transportation struggles ultimately crippled its mining potential.

You’ll find that despite ambitious infrastructure investments like the Pacific and Idaho Northern Railroad’s planned route through Cuprum to Landore, legal battles among mine owners derailed these transportation innovations. Only a half-mile of railroad grade near Helena was completed before work halted.

Modern ghost town explorers can still visit the remnants of these failed transportation ventures today. You would’ve witnessed the miners’ reliance on slow pack trains and wagons, struggling against the region’s harsh mountainous terrain near the Snake River.

These inefficient transport methods drastically inflated operational costs – in 1960, extracting $400,000 worth of copper cost a staggering $1.6 million.

Without proper roads or rail service, shipping ore and supplies remained prohibitively expensive, leading to the mines’ eventual abandonment and Cuprum’s transformation into a ghost town.

The Economics Behind the Decline

Despite ambitious mining efforts throughout Cuprum’s history, crushing economic realities doomed the town’s copper operations from the start.

You’ll find stark evidence in the 1960 figures, when $1.6 million in extraction costs yielded just $400,000 in copper – a devastating loss that reflected the operation’s persistent lack of economic sustainability.

The town’s mining profitability faced relentless challenges: difficult terrain that prevented efficient open-pit mining, declining global copper prices, and fierce competition from more viable operations like Utah’s Bingham Canyon.

You couldn’t establish a stable workforce in Cuprum’s harsh environment, and attempts to diversify through logging and tourism proved insufficient.

Without secondary industries or sustained external investment, the town remained trapped in mining’s brutal boom-and-bust cycles until its eventual abandonment.

Notable Mining Companies and Their Attempts

You’ll find that several major companies tried their luck in Cuprum’s mineral-rich terrain, from Boston and Seven Devils Copper Company’s ambitious $1,000,000 investment in the early 1900s to Noranda and Silver King Mines’ operations in the 1960s-70s.

Silver King proved most successful, expanding the Copper Cliff Mine’s reserves to over 2 million tons of ore and shifting from underground to open-pit mining to boost production to 800 tons daily.

While smaller operators like Sunshine Mining Company and Copper Ridge attempted to establish profitable ventures, they struggled against the region’s challenging geology and the persistent Kleinschmidt grade problem, ultimately failing to achieve long-term success.

Major Mining Operations History

Although Cuprum’s early mining era attracted numerous prospectors drawn to visible copper outcroppings, large-scale mining operations didn’t emerge until the 1960s.

You’ll find that Silver King Mines, under K.L. Stoker’s leadership, brought modern mining technology to the area, altering the economic impact of the region.

The most significant development came in 1973 when the Copper Cliff Mine expanded its reserves to over 2 million tons of copper-silver ore.

By 1974, they’d upgraded their concentrator to process 800 tons daily, shifting from underground to open-pit mining.

Production that year yielded 409 short tons of copper worth $630,000 and over 20,000 ounces of silver.

Despite these achievements, the challenging terrain and high operational costs via Kleinschmidt Grade ultimately limited long-term success.

Failed Ventures And Litigation

While many mining ventures showed initial promise in Cuprum, one of the earliest setbacks came with the 1891 Snake River steamboat landing project.

You’d think investing $20,000 in a riverside landing would’ve secured Cuprum’s transportation future, but this failed investment proved otherwise. The ambitious landing, meant to serve the burgeoning mining district, stood as a symbol of the region’s boom-and-bust nature.

Like many frontier development projects, it represented both the boundless optimism and harsh realities of Western expansion. Those who sank their money into the steamboat landing learned a costly lesson about the unpredictable nature of mining infrastructure investments.

The project’s failure foreshadowed the legal disputes and financial challenges that would later plague other mining ventures in the area.

Present-Day Ghost Town Experience

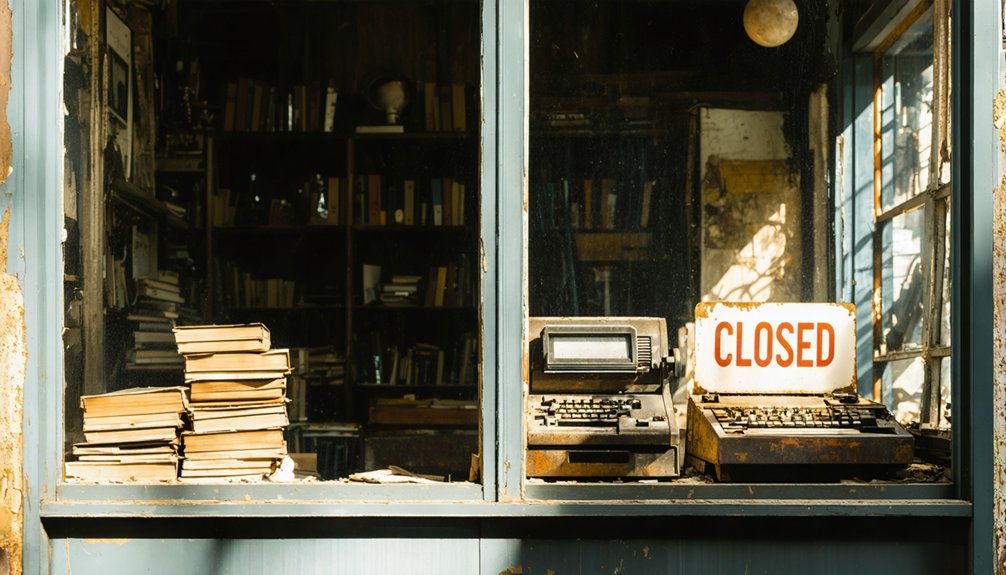

Unlike many abandoned mining settlements that have crumbled into complete ruins, Cuprum stands as a quiet mountain hamlet with nine year-round residents and scattered summer cabins.

As you explore this ghost town at 4,298 feet elevation, you’ll find well-maintained structures rather than deteriorating remains. The unpaved mountain roads leading 27 miles northwest of Council offer you a genuine sense of visitor solitude in Idaho’s rugged terrain.

You won’t find tourist amenities, guided tours, or interpretive displays here. Instead, you’ll discover a self-guided experience among original buildings and peaceful mountain surroundings.

While winters can make access challenging, the warmer months invite you to explore this remote community where nature has largely reclaimed what was once a bustling mining operation.

Legacy in Idaho’s Mining History

When precious metals were discovered in Cuprum around 1893, few could have predicted the town’s modest yet meaningful role in Idaho’s mining legacy. Named after the Latin word for copper, this remote settlement carved its place in the state’s cultural heritage through determined underground mining operations that began around 1905.

While you won’t find the extensive production numbers of Idaho’s larger mining districts here, Cuprum’s story adds an important chapter to the state’s historical preservation efforts. The town’s peak saw about 100 residents, a post office, and a hospital, all supporting the challenging work of extracting copper, gold, and silver from the rugged terrain along Indian Creek.

Today, the area’s geological significance continues to attract interest, with ongoing efforts to develop both old and new mining opportunities.

Frequently Asked Questions

Are There Any Paranormal Activities Reported in Cuprum’s Abandoned Buildings?

You won’t find documented ghost sightings in Cuprum’s buildings, unlike other haunted locations in Idaho. While nearby ghost towns have paranormal reports, there aren’t credible accounts of supernatural activity in Cuprum’s remains.

What Happened to the Medical Equipment From Cuprum’s 1897 Hospital?

You won’t find those medical relics today – they’ve vanished into history. Records don’t show if the equipment was salvaged, stolen, or simply deteriorated, though their historical significance remains intriguing.

Can Visitors Stay Overnight in Any of Cuprum’s Remaining Structures?

Like a shuttered window in moonlight, you can’t stay in Cuprum’s structures. They’re unsafe and off-limits. For overnight visits, you’ll need to find ghost town accommodations elsewhere or consider overnight camping nearby.

What Native American Tribes Originally Inhabited the Cuprum Area?

You’ll find the Nez Perce, Shoshone, and Bannock tribes were the original Native tribes of historical significance in this region, moving freely through the area’s mountains and valleys for hunting and gathering.

Does Cuprum Experience Extreme Weather Conditions That Affect Access to the Town?

You bet your boots it does! Winter storms pack a serious punch, bringing heavy snow, freezing rain, and gusty winds that’ll make access challenging through those remote mountain roads.

References

- http://pnwphotoblog.com/ghost-town-cuprum-idaho/

- https://history.idaho.gov/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/0116.pdf

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IZJVOQFucFY

- https://www.rickjust.com/blog/helena-the-one-in-idaho

- https://www.familysearch.org/en/wiki/Cuprum

- https://www.idahogeology.org/pub/Staff_Reports/1997/S-97-4.pdf

- https://www.ghosttowns.com/states/id/cuprum.html

- https://www.idahogoldmining.com/claims-for-sale/cuprum/

- https://history.idaho.gov/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/0115.pdf

- https://www.mindat.org/loc-3731.html