Across America, you’ll find abandoned logging communities from the Pacific Northwest to the Southern Pine Belt and Great Lakes region. These ghost towns emerged during the 19th-century timber boom before rapid resource depletion led to their decline by the 1930s. Look for moss-covered machinery, decaying mill foundations, and company town remnants now being reclaimed by forests. Each silent site tells a compelling story of dangerous work, corporate control, and the boom-bust cycle of America’s timber frontier.

Key Takeaways

- Abandoned logging communities can be found throughout New England, the Great Lakes, Pacific Northwest, and Southern Pine Belt regions.

- Port Gamble preserves 19th-century lumber town architecture while most sites feature decaying remnants of timber operations.

- Ghost towns like Maxville and Grisdale showcase the rise and fall of the logging industry from the 1800s to mid-1980s.

- Archaeological excavations and museums now document these communities’ multiracial histories and technological evolution.

- Abandoned railroad grades, boom ponds, and moss-covered equipment remain as silent testimonies to logging’s golden age.

The Rise and Fall of Timber Boom Towns

While America’s timber industry now operates primarily as a sustainable resource, it once functioned as an extractive industry that spawned hundreds of boom towns across the nation.

You can trace timber history from New England’s depleted forests in the mid-19th century to the westward migration of lumbermen seeking virgin forests in the Great Lakes region and Pacific Northwest.

The logging industry expanded dramatically with railroad development in the late 1800s. Towns like Teekalet (Port Gamble) in Washington Territory emerged as early as 1853, while Minnesota’s boom followed the harvesting of white pine along the St. Croix River.

These communities thrived with technological advances like band saws and steam power, but their single-resource economies created vulnerability. Prior to the Civil War, the timber industry supplied over 90% of energy needed for America’s growing industrial operations. Inventions such as the Dolbeer donkey engine revolutionized logging by allowing the movement of massive logs over considerable distances. When surrounding forests were exhausted, these once-bustling communities faced inevitable decline, abandoned as the industry moved elsewhere.

Pacific Northwest: Ghosts Among Ancient Forests

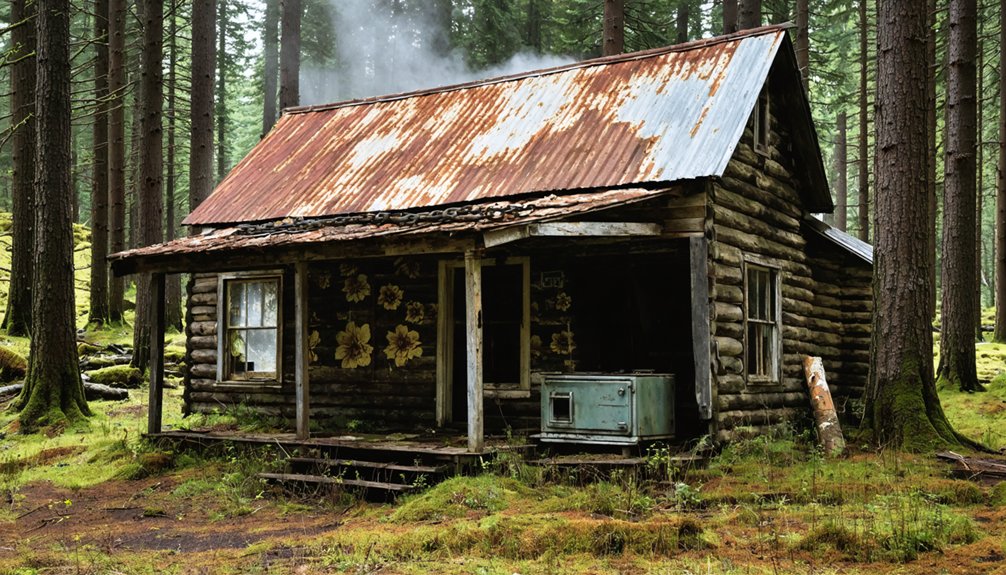

If you’re exploring the Pacific Northwest‘s abandoned logging sites today, you’ll find the decaying remnants of once-thriving timber operations where massive railroad trestles stand 60 feet tall with trees growing through their structures.

These ghost towns, documented in 1940s topographic maps but now reclaimed by forest, contain concrete foundations, scattered colored glass fragments, and metal artifacts that tell stories of companies like Pope & Talbot who established the first timber town in Washington Territory at Teekalet in 1853. Often, these sites can be located by following the old railroad grades that once served as transportation routes for both logs and workers.

One such vanished community is Maxville, which became a ghost town after severe winter storms in the mid-1940s caused structural collapses throughout the once-vibrant logging settlement.

The region’s last active logging camp, Grisdale, operated until the mid-1980s, marking the final chapter of an industry that once built entire communities complete with segregated housing, schools, and churches to support the diverse workforce that harvested the ancient forests.

Timber Titans’ Final Stand

Amid towering Douglas firs and ancient redwoods, the Pacific Northwest’s logging communities once thrived as bustling epicenters of America’s timber industry.

You’ll find their timber legacy scattered through remote valleys where railroads once carried men and equipment deep into virgin forests. Similar to towns like Liberty and Govan, these logging communities gradually declined when industries shifted and transportation routes changed.

These company towns represented both innovation and exploitation. Workers endured dangerous conditions for meager wages while lumber barons built their empires.

When you explore abandoned sites today, you’ll notice remnants of logging innovations: decaying trestles, rusted machinery, and crumbling foundations. The concentration of wealth became evident as companies like Weyerhaeuser acquired vast stretches of private timberland throughout Washington and Oregon.

Moss-Covered Mill Remnants

Beneath the emerald canopy of the Pacific Northwest’s recovering forests, you’ll find the decaying skeletons of America’s timber industry golden age.

These moss-covered memories tell stories of once-thriving communities that harvested two square miles of ancient forest weekly, now surrendering to nature’s reclamation.

Physical evidence of this logging era remains scattered throughout Washington and Oregon:

- Boom ponds where thousands of logs once floated, now transformed into serene wetlands

- Port Gamble’s preserved 19th-century structures, standing as the finest example of lumber town architecture

- Remnants of temporary dams that dramatically altered stream channels during log drives

- Abandoned railroad grades cutting through forests, slowly disappearing under verdant growth

The introduction of steam donkeys in the 1880s revolutionized logging operations, leaving behind rusted machinery parts as silent testaments to the industry’s technological evolution.

What once powered the region’s economy now exists as archaeological whispers among second-growth forests, gradually erased by time’s persistent march.

By 1910, Washington State had become the nation’s largest lumber producer, transforming small settlements into bustling logging towns that now stand abandoned.

Southern Pine Belt: Forgotten Communities of the Piney Woods

Across the Southern Pine Belt, you’ll find the weathered remains of company towns that once formed a vast “sawdust empire” during the timber boom of the late 1800s through early 1900s.

These communities flourished briefly as northern capital transformed isolated forest tracts into industrial hubs, complete with company stores, worker housing, and extensive rail networks built to extract virgin yellow pine. East Texas became a central focus when investment capitalists shifted their attention from Great Lakes forests to southern pine resources.

Mississippi’s Piney Woods counties, part of a coastal plain stretching from Virginia to Texas, saw their river towns experience severe economic decline after the 1920s as large mills shut down due to forest depletion.

Today, only scattered foundations, overgrown rail beds, and occasional ghost towns remain, silent testimony to an industry that treated the region’s forests as inexhaustible before collapsing amid resource depletion and the economic pressures of the Great Depression.

Company Towns’ Rise

As the nineteenth century drew to a close, the vast pine forests of the American South became the target of aggressive industrial expansion that would fundamentally reshape the region’s landscape and communities.

The company town dynamics emerged quickly as lumber corporations established complete settlements near rail lines, controlling every aspect of workers’ lives while maximizing timber production impact.

These corporate-designed communities flourished alongside the railroad expansion, creating efficient timber extraction systems across the Southern Pine Belt:

- Towns like Laurel, Mississippi became global yellow pine shipping leaders by the early 1900s.

- Companies provided housing, commissaries, and recreational facilities, fostering worker loyalty.

- Mill operations required daily processing of extensive timber acreage.

- Towns were strategically positioned near railroads for efficient log transportation.

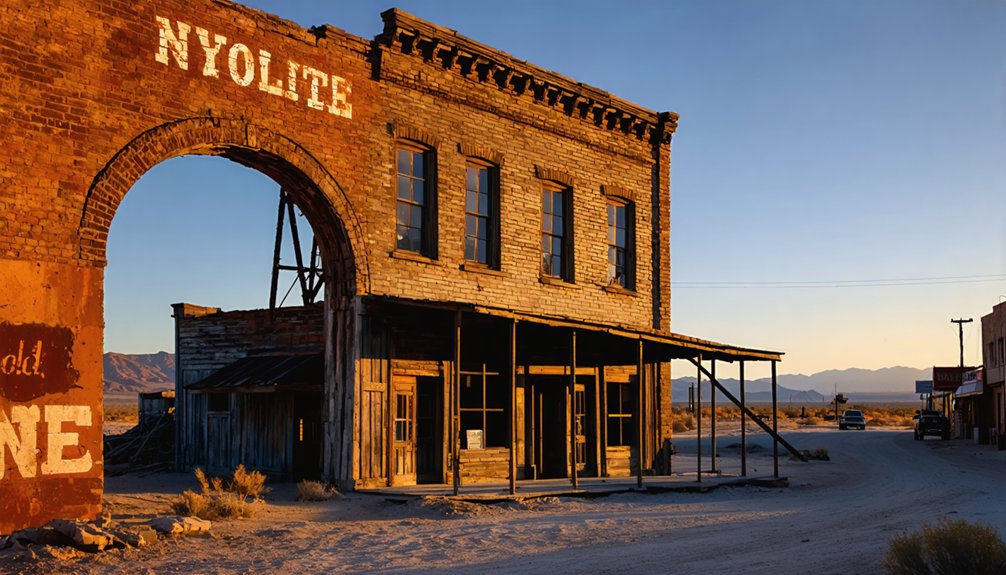

Sawdust Empire Collapse

The sprawling lumber empires that dominated the Southern Pine Belt would face their inevitable reckoning by the early twentieth century.

You’d discover that the 1909 peak in yellow pine production marked the beginning of the end for this sawdust legacy. Within decades, what foresters predicted in 1908 came true—virgin forests that had stood untouched for centuries vanished by 1930.

The railroad revolution that once enabled the timber boom ultimately facilitated its collapse.

As you explore these forgotten communities, you’ll find that smaller mills perished first, unable to compete when timber became scarce.

The logging narratives of places like Cedar Creek and L.O. Crosby’s vast holdings reveal how quickly an entire economic system could rise and fall, leaving behind ghost towns where thousands once labored in the now-silent Piney Woods.

Remnants Among Pines

Today, scattered remnants of once-thriving communities dot the Southern Pine Belt landscape, marking where thousands of workers once converted ancient forests into America’s lumber supply.

What began with a single sawmill in 1829 exploded after 1880 when railroads penetrated virgin forests, enabling unprecedented timber extraction that peaked in 1909.

Exploring these forgotten company towns, you’ll discover:

- Mill ponds and dam structures that once formed the industrial centers

- Abandoned spur line routes where McGiffert loaders once stacked logs

- Building foundations from hastily constructed worker housing

- Logging artifacts from the region’s brief but intense industrial period

These physical remnants tell the story of communities that vanished when the ancient longleaf pines—now reduced to just 3% of their original range—could no longer support the industry, highlighting the importance of heritage preservation.

Great Lakes Logging Heritage: Michigan’s Lost Settlements

Michigan’s once-thriving logging settlements emerged and disappeared during a remarkably brief but intense period of resource extraction that transformed the state’s landscape forever.

The ghost towns of Michigan’s lumber era stand as monuments to the rapid rise and fall of an industry that reshaped the wilderness.

When you visit these ghostly remnants, you’re witnessing the aftermath of America’s most dramatic timber harvest—over 160 billion board feet extracted between 1840-1910, with peak activity concentrated in just 20 years.

The state’s logging legacy began with white pine, which floated easily down Michigan’s extensive river networks to bustling mill towns like Saginaw.

Once pines vanished around 1895, operations shifted to hardwoods and hemlock, particularly in the Upper Peninsula.

By 1910, most logging communities had been abandoned, their economic purpose exhausted.

Today’s forest restoration efforts represent a dramatic reversal from the clear-cutting that once stripped Michigan entirely of its ancient forests.

Life in Company Towns: The Social Fabric of Logging Communities

While frontier forests were being systematically harvested throughout America’s logging boom, unique social ecosystems emerged in the form of company towns, where every aspect of daily life operated under corporate control.

In these isolated outposts, you’d find your community dynamics shaped by rigid hierarchies with managers receiving superior housing while laborers occupied basic quarters.

When examining logging communities, you’ll discover:

- Labor relations often became contentious as workers’ complete dependence on company housing and scrip currency limited their bargaining power.

- Social activities were company-sponsored to maintain morale and control.

- Family isolation created tight-knit communities despite harsh conditions.

- Stratification existed in everything from housing quality to access to amenities.

Your existence in these towns meant trading independence for stability in remote wilderness settings.

What Remains: Exploring the Physical Remnants Today

As you traverse the forgotten landscapes of America’s abandoned logging communities, a physical tribute to the industry’s boom-and-bust cycle emerges through deteriorating structures and discarded equipment.

Hand-hewn cedar cabins stand defiant against time, their mud chinking revealing original construction methods. The decay dynamics unfold as nature reclaims these spaces—apple trees marking former homes while forest growth conceals dangerous mineshafts.

These weathered structures tell silent tales—architectural ghosts surrendering to nature’s patient reclamation.

Metal detecting enthusiasts engage in artifact analysis, uncovering Civil War-era weaponry, tools, and personal items that tell stories of daily life.

You’ll find A-frame logging rigs slowly sinking into coastal waters and machinery rusting beneath encroaching vegetation.

Be cautious—structural instability, hidden shafts, and deteriorating infrastructure create hazards throughout these ghost towns where thousands of dollars in equipment was simply abandoned when the industry collapsed.

Preserving Logging History: From Decay to Cultural Treasures

Once scattered across America’s forested regions as thriving industrial centers, abandoned logging communities now face a critical shift from forgotten decay to preserved cultural treasures. Heritage preservation efforts focus on protecting these vanishing cultural landscapes before they disappear entirely.

You’ll find these preservation approaches taking multiple forms:

- Archaeological excavations at sites like Maxville that uncover artifacts revealing multiracial histories previously overlooked.

- Community storytelling through oral history projects capturing memories from workers’ descendants.

- Museum and interpretive center development showcasing technological evolution and labor contributions.

- Digital archives documenting these ephemeral communities through photographs and records.

These efforts not only rescue physical remnants but reclaim marginalized narratives of immigrant, Native American, and African American loggers whose contributions shaped America’s development while fostering appreciation for both cultural heritage and environmental transformation.

Frequently Asked Questions

Are Abandoned Logging Towns Safe for Visitors to Explore?

You’ll encounter serious safety concerns from deteriorating structures and environmental hazards. Visit only preserved historical sites with proper permissions, as many abandoned logging towns remain dangerously unstable for exploration.

What Specialized Equipment Did These Communities Use for Timber Harvesting?

You’d find timber tools like Lombard tractors, A-frame rigs, steam donkeys, and skidders. These logging machinery innovations allowed communities to extract logs efficiently from challenging terrain across diverse forests.

How Did Women Contribute to Logging Community Economies?

Like invisible pillars, women upheld logging economies through diverse roles—cooking, bookkeeping, and wartime production. You’ll find their economic impact threaded throughout camp operations, sustaining productivity while breaking traditional boundaries.

Did Any Logging Communities Successfully Transition to Sustainable Industries?

Yes, you’ll find numerous logging communities embraced sustainable practices, shifting to forest management, renewable energy, and ecotourism. Their community resilience developed through certification programs and local decision-making systems that prioritized environmental stewardship.

What Supernatural Legends Emerged From These Isolated Logging Settlements?

Like whispers through forgotten timber, you’ll find ghost stories of vengeful spirits and protective apparitions emerged from these settlements. Folklore traditions often connected supernatural phenomena to logging disasters, industrial decline, and isolated mountain tragedies.

References

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_the_lumber_industry_in_the_United_States

- https://www.texasbeyondhistory.net/aldridge/logging.html

- https://www.nps.gov/bith/learn/historyculture/logging.htm

- https://www.dnr.state.mn.us/forestry/history/logging-camps.html

- https://www.americanforests.org/article/north-american-forests-in-the-age-of-man/

- https://www.fs.usda.gov/sites/default/files/legacy_files/media/types/publication/field_pdf/forestfacts-2014aug-fs1035-508complete.pdf

- https://www.ran.org/the-understory/how_much_old_growth_forest_remains_in_the_us/

- https://www.ebsco.com/research-starters/forestry/history-global-logging-industry

- https://esajournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1890/09-0217.1

- https://www.historylink.org/File/23208