You’ll find Duncan’s Retreat three miles east of Virgin, Utah, where Mormon pioneer Chapman Duncan established a cotton-growing settlement in 1861. Despite initial promise, the community faced severe challenges from poorly planned irrigation and devastating Virgin River floods, particularly the Great Flood of 1862. The population peaked at 79 residents in 1880 before declining sharply, and by 1895, repeated flooding forced complete abandonment. The site’s dramatic story captures both the determination and limitations of Utah’s early Mormon settlements.

Key Takeaways

- Duncan’s Retreat was a Mormon settlement founded in 1861 near Virgin, Utah, that became abandoned by 1895 due to persistent flooding.

- The community’s population peaked at 79 residents in 1880 before declining dramatically to 47 people by 1890.

- Poor irrigation planning, including a canal that ran uphill, combined with alkaline soil made farming extremely challenging for settlers.

- The Great Flood of 1862 devastated the settlement, destroying infrastructure and forcing residents to temporarily abandon their homes.

- The ghost town’s location along Mukuntuweap Creek and the Virgin River ultimately proved unsuitable for sustained agricultural development.

The Birth of a Desert Settlement

While Brigham Young sought to establish cotton production in Utah’s Dixie region, Chapman Duncan led a small group of Mormon settlers to establish a new community along Mukuntuweap Creek in late 1861.

You’ll find the settlement’s location about three miles east of present-day Virgin, Utah, where Duncan, Alma Minerly, and their companions braved the harsh desert environment to create a farming outpost.

The winter of 1861-1862 marked their first season in this unforgiving terrain, as they faced immediate settlement challenges. Duncan’s irrigation efforts were hindered when he made a critical surveying ditch error that impacted water flow to the fields.

A dozen pioneering families worked the land, cultivating diverse crops including corn, wheat, sorghum cane, and cotton.

Despite their determination to cultivate cotton and establish a self-sufficient community, agricultural failures loomed.

The settlers’ dreams would soon be tested by nature’s fury, as they struggled to tame the wild Virgin River tributary for irrigation in this remote corner of the Utah Territory.

Geography and Natural Setting

You’ll find Duncan’s Retreat nestled in eastern Washington County‘s rugged desert terrain, where the Virgin River carved its path through the arid landscape at coordinates 37°11′N, 113°8′W.

The settlement’s position near Utah State Route 9, just three miles east of Virgin and southwest of Zion National Park, placed it squarely within Utah’s Dixie region of stark desert vistas and dramatic rock formations.

The Virgin River’s proximity proved both a blessing and curse, providing essential water for irrigation while subjecting the settlement to unpredictable floods that repeatedly washed away cultivated lands and ultimately contributed to its abandonment. Chapman Duncan established the settlement in 1861, leading the first wave of pioneering families to the area.

Rugged Desert Landscape

The rugged terrain of Duncan’s Retreat emerges from eastern Washington County’s dramatic landscape, nestled within southwestern Utah’s high desert near Zion National Park.

You’ll find elevations ranging from 3,000 to 4,000 feet, where steep slopes and mesas dominate the Colorado Plateau terrain. The area’s harsh desert flora includes drought-resistant sagebrush and scattered patches of native grasses clinging to poor, sandy soils.

Mukuntuweap Creek has carved through layered sandstone and shale, creating a challenging environment where seasonal monsoons can trigger flash floods.

The geology tells a story millions of years in the making – exposed rock formations shaped by wind and water erosion.

You’re witnessing a landscape where nature’s forces continue to sculpt dramatic desert scenery through canyons and weathered cliffs.

Virgin River Proximity

Situated on the north bank of the Virgin River, Duncan’s Retreat took advantage of a strategic location where Mukuntuweap Creek joins the powerful waterway.

You’ll find this ghost town about 3-4 miles east of Virgin, Utah, just southwest of what’s now Zion National Park. The settlement’s proximity to both water sources proved to be a double-edged sword – while essential for survival and irrigation attempts, it also created significant settlement vulnerability.

The river’s unpredictable dynamics shaped Duncan’s Retreat’s fate. During the Great Flood of 1862, the Virgin River’s devastating surge forced settlers to temporarily abandon their homes. Like many similar settlements, the town struggled with crop destruction and erosion due to frequent flooding.

Early irrigation efforts faced challenges too, with poorly planned canals that couldn’t properly harness the volatile water flow, ultimately contributing to the settlement’s demise. Like many who left Duncan’s Retreat, some residents relocated to Hinckley City Cemetery where they were later laid to rest.

Chapman Duncan’s Vision

Driven by Brigham Young’s ambitious cotton-growing initiative, Chapman Duncan established his settlement along Mukuntuweap Creek in 1861, envisioning a thriving agricultural community in southern Utah’s challenging terrain. His aspirations centered on creating a sustainable settlement through carefully planned irrigation systems that would transform the rugged landscape into productive farmland.

Having previously worked rafting with Dudley in Montrose to support his family, Duncan drew upon his resourcefulness to establish the new settlement. His vision included an elaborate canal system to harness Virgin River water. Irrigation challenges emerged when a significant canal survey reportedly ran uphill. The settlement’s location was strategically chosen for agricultural potential. Despite setbacks, Duncan’s dream represented the pioneering spirit of taming Utah’s harsh environment.

A devastating flood in January 1862 destroyed much of the farmland and forced many settlers to abandon their homesteads. The settlement’s early development reflected both the determination and limitations of 1860s frontier engineering in conquering nature’s obstacles.

The Great Flood of 1862

During the winter of 1861-1862, a catastrophic flood devastated vast stretches of the American West, releasing unprecedented destruction on Duncan’s Retreat and neighboring settlements.

The flood’s impact extended far beyond California, reaching deep into Utah Territory after six weeks of relentless rain and snowfall.

You’d have witnessed floodwaters swelling rivers and creeks around Duncan’s Retreat as warm storms melted mountain snow.

The settlement disruption was severe – destroying crucial infrastructure, farmland, and livestock that frontier families depended on.

While exact casualty figures for Duncan’s Retreat aren’t known, the region’s isolation and limited resources made recovery especially challenging.

Standing water persisted for months, forcing many residents to abandon their homes and seek higher ground, forever altering the community’s trajectory.

Early settlements throughout Washington County faced near destruction from the devastating floods on the Virgin and Santa Clara Rivers.

The disaster echoed across the West with devastating economic impacts, as a quarter of California’s cattle perished and the state went bankrupt.

Life in Early Duncan’s Retreat

When Chapman Duncan and Alma Minnerly established Duncan’s Retreat in late 1861, they’d joined Brigham Young’s ambitious Cotton Mission to transform Utah’s Dixie into a cotton-producing region. The settler hardships were immense, with families living in tents, wagons, and dugouts while working to build permanent homes and cultivate the challenging land.

Like many settlements in the region, residents faced severe struggles with alkaline soil conditions, making farming especially difficult.

You’d find the community working together to construct essential irrigation ditches and dams.

Your daily routine would revolve around tending cotton, corn, wheat, and sorghum cane crops.

From sunrise to sunset, settlers labored in the fields, carefully tending their vital crops of cotton, corn, wheat, and sorghum cane.

You’d share labor with local Paiutes, who initially helped with farming and household tasks.

You’d send your children to the newly built schoolhouse starting in 1864.

Your survival would depend on community cooperation to combat the Virgin River’s constant flooding threats and maintain farmable land.

Population Changes Through the Years

You’ll find Duncan’s Retreat’s population journey traced through census records that show 71 residents in 1870 growing modestly to 79 by 1880.

The settlement experienced its most dramatic decline between 1880-1890 when numbers fell 40.5% to just 47 people.

Virgin River flooding proved relentless in driving families away, leading to the community’s eventual abandonment by 1895.

Census Records Show Decline

As Duncan’s Retreat struggled to establish itself as a permanent settlement, census records clearly documented its population trajectory from growth to decline.

Census trends revealed an initial increase from 71 residents in 1870 to 79 by 1880, showing a brief period of optimism.

However, you’ll find the demographic shifts turned sharply downward, with only 47 residents remaining by 1890.

- The 1870 census marked the town’s first official population count at 71 residents

- An 11.3% growth occurred between 1870-1880, reaching 79 inhabitants

- The 1890 census revealed a dramatic 40.5% population drop to 47 people

- Census records ended after 1890 as the town faced near-total abandonment

- Government documentation provided vital evidence of the town’s decline through reliable population tracking

Growth Then Sharp Drop

The Mormon settlement of Duncan’s Retreat experienced dramatic population swings during its brief existence, beginning with Chapman Duncan’s initial group of settlers in 1861.

You’ll find that by 1864, the community had grown to about 50 people across 8 families, reflecting the promise of cotton farming in Utah’s warm southern climate.

Despite various settlement challenges, including Indian troubles and agricultural instability, the population showed resilience through the 1870s and 1880s, reaching 71 residents in 1870 and climbing slightly to 79 by 1880.

However, you can trace the settlement’s ultimate downfall to the persistent flooding of the Virgin River, which repeatedly destroyed farmland and irrigation systems.

Families Leave After Floods

Devastating floods marked the beginning of Duncan’s Retreat’s population decline, starting with the Great Flood of January 1862 that destroyed most of the settlement’s farming land and infrastructure.

The flood impact drove Chapman Duncan and many original settlers away, though by 1863 about 70 new residents moved in to try their luck at farming.

You’ll see the town’s struggle through census numbers – 71 people in 1870, 79 in 1880, then dropping to 47 by 1890.

- Virgin River’s constant flooding destroyed crucial irrigation systems

- Families faced endless repairs to dams and ditches

- Indian troubles combined with floods made staying difficult

- Many moved downstream to Virgin City for better farming

Local Tales and Pioneer Stories

While many ghost towns fade into obscurity without memorable tales, Duncan’s Retreat preserved fascinating pioneer stories that explain its unusual name.

You’ll find the most enduring legend centers on Chapman Duncan’s supposed irrigation blunder – a canal allegedly surveyed to run uphill, rendering it useless for water transport. Some versions place this engineering mishap in nearby Virgin, prompting Duncan’s move to what became his namesake retreat.

Chapman Duncan’s failed attempt to build an uphill canal stands as a cautionary pioneer tale of ambition meeting harsh desert realities.

These tales of pioneer perseverance and irrigation challenges symbolize the broader struggles settlers faced when trying to tame Utah’s harsh landscape.

Though the accuracy of these stories remains uncertain, they’ve become powerful symbols of the determination and occasional setbacks that characterized life in Utah’s early settlements.

Historical Legacy in Utah’s Dixie

Located along the unpredictable Virgin River in Utah’s Dixie region, Duncan’s Retreat exemplifies both the determination and ultimate limitations of Mormon cotton settlement efforts in the 1860s.

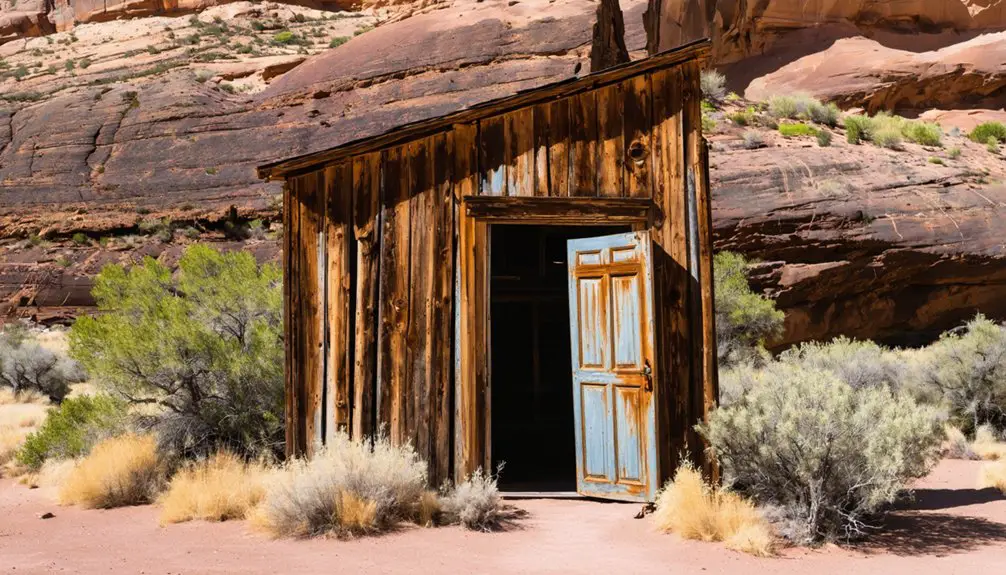

You’ll find a representation of pioneer resilience in the remains of this ghost town, where settlers faced relentless agricultural challenges from flooding and erosion. While the community showed promise with its post office and schoolhouse, nature ultimately prevailed.

- The site’s ruins along Route 9 serve as a stark reminder of early settlement ambitions

- Flooding repeatedly destroyed irrigation systems and farmland, testing settler determination

- Population peaked at 79 residents in 1880 before declining sharply

- The settlement’s story mirrors many failed cotton colonies in Utah’s Dixie

- By 1895, the last residents abandoned their dreams of transforming this harsh landscape

Frequently Asked Questions

Are There Any Remaining Structures or Ruins Visible at Duncan’s Retreat Today?

You’ll find very few remaining buildings at the site today – just Nancy Ferguson Ott’s 1863 grave, fragments of an irrigation ditch, and possibly some rock wall sections as historical artifacts.

What Happened to Chapman Duncan After Leaving the Settlement?

Like many frontier stories, Chapman Duncan’s legacy fades into uncertainty after he sold his claims and left Duncan’s Retreat in 1862. Historical records don’t clearly track his movements or later life.

Did Any Native American Tribes Live in the Area Before Settlement?

Yes, you’ll find the area was historically significant for Native tribes, particularly the Southern Paiute and Ute peoples, who hunted and gathered along the Virgin River for thousands of years.

Can Visitors Legally Explore the Duncan’s Retreat Ghost Town Site?

You’ll find no clear exploration regulations or visitor guidelines at Duncan’s Retreat. Since land ownership isn’t well-documented, you should exercise caution and respect potential private property boundaries while exploring.

Were There Any Notable Businesses or Industries Besides Farming?

You won’t find any mining operations or lumber industry there – farming was the only significant enterprise, mainly focused on cotton, corn, wheat, and sorghum until flooding forced abandonment.

References

- https://graftonheritage.org/history-settlement/

- https://usgenwebsites.org/UTWashington/towns/duncan.html

- https://onlineutah.us/duncansretreathistory.shtml

- https://www.loquis.com/en/loquis/6455103/Duncan+s+Retreat+Utah

- https://www.ghosttowns.com/states/ut/duncansretreat.html

- https://www.routeyou.com/en-us/location/view/51426508?toptext=7791489

- https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/69593/ernest-burgess-theobald

- https://www.legendsofamerica.com/ut-grafton/

- https://dixie4wheeldrive.com/gooseberry_mesa_ghost_town_grafton/

- https://jacobbarlow.com/tag/ghost-towns/page/3/