Dunmovin is a ghost town along Highway 395 in California’s Mojave Desert. Originally Cowan Station, it supported silver mining operations before Charles and Hilda King renamed it in 1936, developing it into a roadside haven with cabins, a café, and store. Ruth and Les Cooper, known as “desert angels,” operated it until the 1970s. Today, you’ll find weathered stone ruins and decaying structures that tell stories of California’s transportation evolution and desert hospitality.

Key Takeaways

- Dunmovin began as Cowan Station in the early 1900s, serving silver mining operations before being renamed in 1936.

- Charles and Hilda King transformed the site into a highway rest stop with a café, store, and tourist cabins.

- The ghost town is located along Highway 395 in the Mojave Desert, about three miles north of Coso Junction.

- Ruth and Les Cooper, known as “desert angels,” operated Dunmovin until the 1970s, aiding stranded travelers.

- Today, weathered stone ruins, burned-out cabins, and abandoned structures remain visible from the highway.

The Origins of Cowan’s Station

While most travelers along U.S. Route 395 speed past the weathered structures of Dunmovin, you’re witnessing the remnants of a significant transportation hub with deep homesteader history.

James Cowan, a Newfoundland native, established Cowan Station in the early 1900s, carving out a strategic outpost in the unforgiving Mojave Desert.

From the far shores of Newfoundland came James Cowan, desert pioneer whose strategic vision tamed the Mojave’s harshest reaches.

Originally situated 10 miles north of Little Lake, the station was later relocated to better serve the freight logistics of the region.

This wasn’t just any waypoint—it was the essential link between Cerro Gordo’s silver mines and Los Angeles markets. Silver ingots traversed harsh desert terrain through this lifeline of commerce.

The station eventually became a vital stop for travelers along the Midland Trail, which later became US-6 and 395.

The station’s placement wasn’t accidental but calculated to support mining operations that fueled California’s economic growth when the West was still being won.

Despite its current abandoned appearance, the area once buzzed with activity as travelers sought roadside amenities during their journeys across the harsh landscape.

From Mining Hub to Highway Rest Stop

You’ll find Dunmovin’s history vividly reflected in its transformation from a silver transport waypoint to a welcome oasis on Route 395.

The station that once handled precious metal shipments from Cerro Gordo mines gradually evolved into a critical rest stop offering fuel, food, and cabins to weary highway travelers. Originally known as Cowan Station, the area served as a freight station in the early 1900s before its evolution. The Kings purchased the property in 1936 and gave it the fitting name Dunmovin that still intrigues passing motorists today.

Silver Transport Legacy

Although nearly forgotten today, Dunmovin’s origins as Cowan Station mark an important chapter in Eastern Sierra’s mining history, transforming from a critical silver transport hub to a welcoming highway rest stop.

As you explore the area, you’re walking the same routes where teamsters once hauled valuable Cerro Gordo silver ingots on their 200-mile journey to Los Angeles.

James Cowan strategically established his station to service these freight operations, providing essential water piped from Talus Canyon—a precious desert commodity. The station offered respite for exhausted crews before they continued their arduous journey. Remi Nadeau’s impressive operation of 80 mule teams by 1873 demonstrated the scale and importance of silver transport through this corridor.

When silver mining declined in the early 1900s, Cowan Station adapted, relocating closer to the emerging Midland Trail to capture automobile traffic, eventually becoming Dunmovin in 1936. Similar to many sites described in Death Valley’s mining history, Dunmovin now faces challenges from weather and neglect, with only scattered remains hinting at its once-bustling past.

Route 395 Oasis

Once Highway 395 became the main artery connecting Los Angeles to the Eastern Sierra, Dunmovin transformed from a forgotten mining station into a welcome roadside haven for weary travelers.

Originally known as Cowan’s Station, this piece of Dunmovin history took a significant turn when Charles and Hilda King purchased the property in 1936, giving it its memorable name.

The site includes what appears to be a former store and several guest cabins that likely housed tired travelers along this scenic mountain route. Access to this abandoned ghost town is restricted as it sits behind a fence with private property signs, deterring casual exploration.

The Kings and the Birth of “Dunmovin”

Transformation came to Cowan Station in 1936 when Charles and Hilda King purchased the struggling freight stop and gave it a name that would reflect their own life journey.

The Kings’ Settlement was aptly named “Dunmovin,” signaling they were finished with wandering and had found their permanent home.

Under their careful stewardship, the old silver freight station evolved into a welcoming highway oasis. They rebuilt and expanded the facilities, adding a cafe, store, and tourist cabins by 1941.

A post office operated briefly from 1938 to 1941, cementing Dunmovin‘s status as a legitimate community.

The Dunmovin Legacy continued until 1961 when the Kings sold the property, but their 25-year tenure transformed what was once merely a stop into a destination that travelers remembered fondly along the desert highway.

Life at a Sierra Nevada Crossroads

Nestled at the eastern base of the imposing Sierra Nevada, Dunmovin emerged as more than just a dot on a highway map—it became a significant crossroads where geography, commerce, and human resilience intersected.

In the shadow of mountain giants, Dunmovin stood as testament to human perseverance at the desert’s edge.

You’d find travelers stopping at the cafe and station, where the Kings and later the Coopers offered respite from the harsh Mojave climate.

Dunmovin history reveals a remarkable adaptation to isolation. The community thrived despite extreme temperature fluctuations and limited resources.

What makes this ghost town particularly fascinating is its unusual spiritual dimension—Father Enrico Molnar’s religious community and the “Desert Angels of Dunmovin” brought desert spirituality to this remote outpost.

While freight operations initially sustained the settlement, it was the human connections forged at this high desert crossroads that defined its character.

A Desert Oasis for Route 395 Travelers

As you cruised along Route 395‘s lonely stretch in the mid-20th century, Dunmovin served as your essential pit stop for fuel, food, and a moment’s respite from the desert heat.

The small station’s stone restaurant and rock cabins welcomed weary travelers with modest comforts in an otherwise unforgiving landscape between Little Lake and Olancha.

Now fenced off and abandoned, the weathered remains of this roadside haven stand as silent witnesses to countless journeys through the Sierra Nevada foothills, its purpose forgotten as modern vehicles speed past without pause. Today, the ghost town at 3,507 feet elevation offers a glimpse into California’s transportation history, where time stands still amid the harsh desert environment.

Roadside Rest Haven

In the harsh expanse of the Mojave Desert, Dunmovin emerged as an essential lifeline for weary travelers traversing Route 395’s isolated stretch between Los Angeles and Reno.

You’d find respite from 110-degree heat and violent winds at this roadside haven, where the Kings and later the Coopers welcomed motorists into their stone restaurant and tourist cabins.

The 160-acre property represented a beacon of roadside nostalgia—a service station, store, and café housed in an old cookhouse offering critical supplies when the next services were miles away.

These forgotten memories of desert hospitality flourished from 1936 through the 1970s, when Gordon and Ruth Cooper maintained the final operations. Just 14.4 miles south of Lone Pine, travelers could also visit the historic Cottonwood Charcoal Kilns along the same highway.

In this unforgiving landscape, Dunmovin earned its name by standing firm as civilization’s outpost amid nature’s extremes.

Highway 395’s Lost Stop

Once a critical waypoint on the lonesome stretch of Highway 395 connecting Los Angeles to the Eastern Sierra, Dunmovin now stands as little more than weathered stone ruins visible from passing cars.

You’ll find this forgotten ghost town three miles north of Coso Junction rest area, though accessing it requires a detour since it sits on the southbound side while the rest area serves northbound travelers.

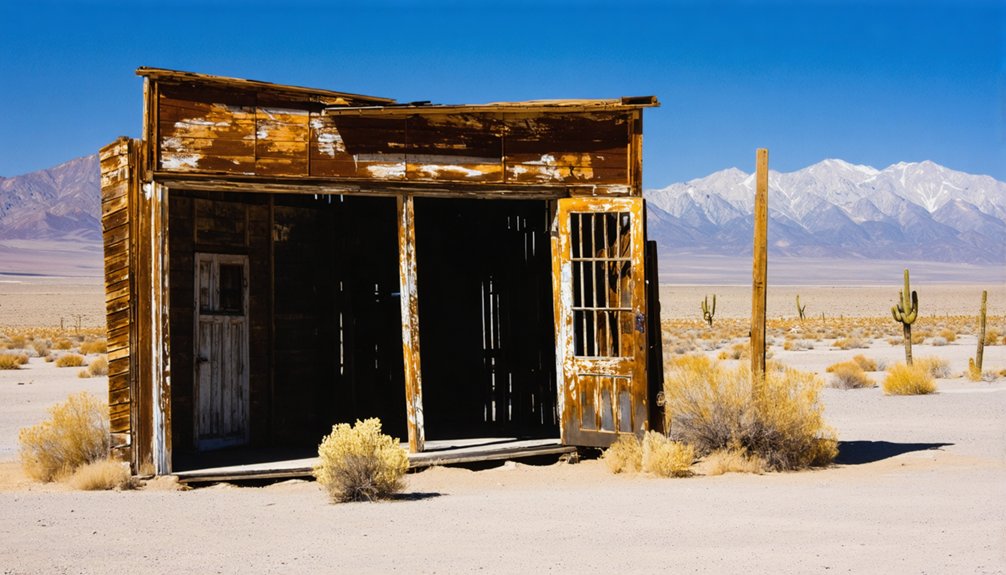

The skeletal remains of cabins, a café, and a store—once welcoming weary motorists with their “done movin'” ethos—now crumble behind “no trespassing” signs at 3,507 feet elevation.

As you drive this well-traveled route to Mammoth or Bishop, these bleak stone structures silently collect travel tales from an era when Highway 395 required more frequent stops in the Mojave’s vast expanse.

Artifacts and Remnants: What Survives Today

The skeletal remains of Dunmovin stand today as haunting symbols to the town’s brief existence along Highway 395.

What’s left reveals the ghost town‘s final chapter: rock-walled foundations, burned-out tourist cabins, and a gutted restaurant/store building with large windows and empty curtain rods.

No caretaker watches over these historical artifacts—they’re completely deserted and exposed to vandalism.

Inside these abandoned structures, you’ll find:

- Remnants of shelving and countertops in the store/restaurant

- Curtain rods and fabric traces suggesting hospitality use

- Personal belongings scattered throughout tourist cabins

- Graffiti and broken windows marking the passage of time

The 161-acre property remains unsold, its buildings slowly surrendering to the harsh desert environment.

The Desert Angels: Ruth and Les Cooper

While the physical remnants of Dunmovin slowly crumble into the desert floor, the spirit of the place lives on through the remarkable story of its most beloved caretakers.

Ruth and Les Cooper, known as the “desert angels,” purchased Dunmovin in 1961, transforming it into a sanctuary of radical desert hospitality. After Les became an attorney in 1943 following a back injury, the couple married in 1949 and settled in the area by 1952.

The Coopers transformed a remote desert outpost into a beacon of boundless compassion and unexpected grace.

Their spiritual ministry extended beyond running the gas station and café—they rescued countless stranded travelers on dangerous Highway 395 and opened their home to abused children and troubled youth.

Operating Dunmovin until the 1970s, the Coopers embodied desert mysticism through practical compassion. Ruth’s recent passing marks the end of an era, though their legacy as desert saints continues through local memory and family descendants.

Exploring an Abandoned High Desert Settlement

Driving along the isolated stretch of Highway 395 in California’s high desert, you’ll spot the skeletal remains of Dunmovin emerging from the parched landscape like ancient ruins.

This ghost town stands as a symbol of desert solitude and California’s transient history, visible yet unreachable behind private property fences.

What once welcomed weary travelers now whispers tales of abandonment:

- Rock-walled structures, now merely shells, housed a service station, café, and store that operated until the 1970s.

- Water from Talus Canyon springs once sustained this small community.

- Original buildings date back to when it was Cowan Station in the early 1900s.

- Despite “no trespassing” signs, you can glimpse the town’s remains from the highway.

The Silent Legacy of a Forgotten Transport Hub

Tucked between the stark Inyo Mountains and the sweeping Owens Valley, Dunmovin once served as a vital transport artery that kept California’s mining economy flowing in the early 1900s.

From its origins as Cowan’s Station to its 1936 rebirth under the Kings, this settlement channeled silver ingots from Cerro Gordo mines to Los Angeles, creating significant economic impacts throughout the region.

You can trace the cultural significance of this ghost town through its evolution from freight station to roadside haven along Route 395.

Water from Talus Canyon springs sustained both travelers and residents until the 1970s, when shifting transportation patterns rendered the once-bustling hub obsolete.

Today, the derelict remains of its service station, cafe, and cabins stand as silent sentinels to California’s forgotten transport history.

Frequently Asked Questions

Are There Any Paranormal or Ghostly Encounters Reported at Dunmovin?

No documented ghost sightings exist for Dunmovin. Unlike other haunted locations in California, this forgotten town’s ruins tell stories of abandonment rather than paranormal activity. You’ll find history, not spirits, here.

What Happened to Dunmovin’s Residents When the Town Was Abandoned?

You’d find residents scattered as town decline took hold. Some, like the Kings, stayed until death. Others, including the Coopers, departed after their businesses failed in the 1970s, seeking opportunity elsewhere.

Is It Legal to Visit or Photograph the Dunmovin Site?

Like many who’ve documented California’s forgotten places, you’ll face legal restrictions at Dunmovin. You can’t legally enter the fenced private property, but you’re free to photograph from public roads alongside Highway 395.

Has Dunmovin Ever Appeared in Films or Television Shows?

No, there’s no documented evidence of Dunmovin’s movie appearances or television features. You won’t find this forgotten outpost in filmographies or location databases that Hollywood history typically preserves.

Were Any Notable Crimes or Tragedies Associated With Dunmovin’s History?

You’ll find no unsolved mysteries or historical hauntings here. Despite ghost town rumors, Dunmovin’s documented history contains no notable crimes or tragedies—just peaceful desert hospitality and eventual economic decline.

References

- https://desertspiritpress.net/2020/01/22/desert-angels-of-dunmovin/

- https://www.exploratography.com/blog-cal/dunmovin-california

- https://www.legendsofamerica.com/ca-deathvalleyghosttownscalifornia/

- http://harryhelmsblog.blogspot.com/2008/09/ghost-town-of-dunmovin-california.html

- http://forgotten-destinations.blogspot.com/2016/11/dunmovin-town-without-trace.html

- https://beyond.nvexpeditions.com/california/inyo/dunmovin.php

- http://cali49.com/mojave/2015/1/28/dunmovin-cal

- http://www.owensvalleyhistory.com/stories/jane_thomann030.pdf

- https://www.loquis.com/en/loquis/6586254/Dunmovin+California

- https://nvtami.com/inyo-county-california-ghost-towns/