Across the US, you’ll find diverse Native American settlement remnants spanning thousands of years of history. From the Southeast’s massive earthen mounds to Southwest cliff dwellings carved into canyon walls, these archaeological treasures reveal sophisticated pre-Columbian societies. Sacred ceremonial centers like Taos Pueblo maintain living connections to ancient traditions, while Eastern Woodland sites showcase extensive trade networks. The preservation of these hidden historical gems offers glimpses into complex civilizations that once thrived on American soil.

Key Takeaways

- Poverty Point in Louisiana stands as North America’s largest prehistoric earthwork, showcasing sophisticated engineering despite limited tools.

- Watson Brake predates many recognized archaeological sites at 3500 BCE, challenging assumptions about early Native American settlements.

- Ancestral Puebloan cliff dwellings in the Four Corners region served as defensive fortresses accessible only by retractable ladders.

- Effigy Mounds near Harpers Ferry include 31 animal-shaped mounds that reveal Eastern Woodland Indians’ complex spiritual practices.

- Trade networks connecting the Great Lakes to the Gulf Coast are evidenced by artifacts found in overlooked archaeological sites.

Mound Building Civilizations of the Southeast

Among the most impressive yet often overlooked architectural achievements in pre-Columbian North America, mound-building civilizations flourished across the Eastern, Southeastern, and Midwestern United States for over 5,000 years.

Beginning around 3500 BCE, indigenous peoples transported millions of cubic feet of earth in woven baskets to create structures with diverse forms and functions. These remarkable earthworks were built in various shapes including cones, rectangles, squares, circular plateaus, and animal figures.

You’ll find evidence of sophisticated engineering at sites like Watson Brake in Louisiana, where 11 mounds connected by earthen ridges form an oval dating to 3500 BCE.

Adena burial practices (1000 BCE-200 CE) incorporated cone-shaped mounds in the Ohio River valley, while later Mississippian cultures constructed flat-topped pyramidal platforms for elite residences and temples.

Mound construction evolved from simple rounded forms to complex structures featuring ramps and specialized layouts, with the Lamar site’s unique spiral ramp representing the pinnacle of this architectural tradition. The most impressive example is Monks Mound at Cahokia, which served as a major agricultural center with a large temple atop its summit.

Cliff Dwellings and Desert Settlements of the Southwest

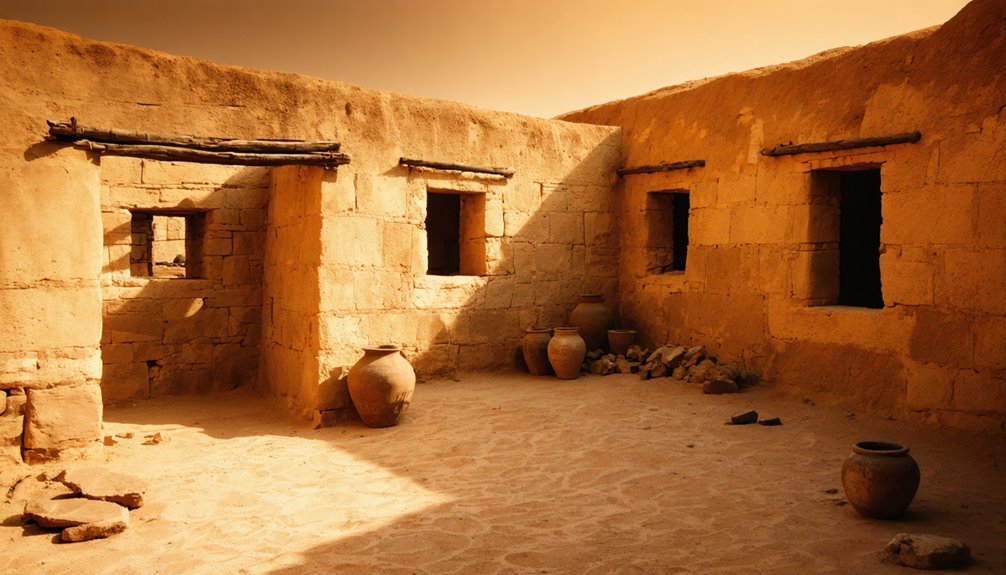

While mound builders transformed the eastern landscapes with earth architecture, the American Southwest witnessed another remarkable form of indigenous construction. Between 500-1300 CE, Ancestral Puebloans carved sophisticated settlements into cliff faces across the Four Corners region, creating defensive fortresses accessible only by retractable ladders.

As eastern civilizations sculpted earth into monumental mounds, the Southwest’s ancient Puebloans engineered remarkable cliff dwellings, accessible only by removable ladders.

This cliff architecture represents a strategic adaptation to environmental pressures and potential conflicts. Multistory structures featured sandstone masonry, wooden beams, and adobe mortar, with underground kivas serving as ceremonial centers. The Anasazi culture developed these distinctive cliff dwellings that reflected their advanced architectural skills.

Sites like Mesa Verde housed complex communities of up to 800 rooms. Bandelier National Monument offers visitors a rare opportunity to enter cliff dwellings using traditional ladders, similar to how the original inhabitants accessed their homes.

The shift to these settlements corresponded with ancient agriculture practices, as nomadic lifestyles gave way to sedentary maize cultivation. Extended droughts (1276-1299) eventually forced abandonment of these settlements, though their engineering sophistication remains proof of Puebloan ingenuity and adaptation.

Sacred Ceremonial Centers and Their Ongoing Legacy

Beyond the physical remnants of prehistoric settlements, sacred ceremonial centers represent living connections between Native American tribes and their ancestral heritage. You’ll find these sites on federal or tribal lands, protected under Executive Order 13007, where active cultural practices continue uninterrupted.

Notable examples include Taos Pueblo, continuously inhabited for over 1,000 years, and Ocmulgee National Monument with earthworks dating back 10,000 years. Their ceremonial significance extends beyond historical value—these are living spaces where language revitalization, traditional rituals, and cultural preservation efforts thrive. The UNESCO World Heritage site of Taos Pueblo stands majestically against the mountains as a testament to indigenous architectural ingenuity. Chaco Culture National Historical Park in New Mexico showcases the sophisticated astronomical alignments in its ancient architecture.

When visiting, respect access restrictions and photography limitations. Many sites offer tribal-led tours, but remember: these aren’t merely tourist attractions.

Through legal protections, cultural easements, and tribal oversight, these centers maintain their spiritual integrity while educating the public about Native American heritage.

Overlooked Archaeological Treasures in the Eastern Woodlands

The Eastern Woodlands region harbors archaeological treasures that have remained largely unrecognized by the general public despite their significant cultural and historical value.

You’ll find monumental mound complexes like Poverty Point, North America’s largest prehistoric earthwork, and the ancient Watson Brake, dating to 3500 B.C.E.—predating many acknowledged sites.

These cultures established sophisticated trade networks spanning from the Great Lakes to the Gulf Coast, evidenced by copper, shells, and bannerstones found far from their origins.

Their burial practices reveal complex social structures, particularly at sites like Moundville and Spiro’s Craig Mound, where elaborate mortuary treatments and elite graves contained copper plaques and effigy pipes.

The labor required for constructing massive geometric earthworks and temple mounds demonstrates these societies’ sophisticated organizational capabilities.

Notable sites like Aztalan and Cahokia showcase how Native Americans developed advanced agricultural practices that supported large urban settlements with populations reaching up to 20,000 inhabitants.

Effigy Mounds near Harpers Ferry, Iowa contains impressive earthworks with 31 animal-shaped mounds representing birds, mammals, and reptiles that were constructed by Eastern Woodland Indians centuries before European contact.

Preserving Ancient Native American Heritage Sites

As federal and tribal authorities grapple with balancing preservation and development, a complex framework of legislation has emerged to safeguard Native American heritage sites across the United States. The 1966 National Historic Preservation Act established essential protections, later strengthened by its 1992 amendments that empowered tribes to assume preservation authority on trust lands.

You’ll find indigenous stewardship manifested through Tribal Historic Preservation Officers (THPOs), who now represent over 170 tribes in cultural resource management efforts.

These officers identify Traditional Cultural Properties while maneuvering the sensitive disclosure of sacred sites. Their work integrates specialized tribal knowledge with modern preservation techniques, creating protection systems that respect both scientific and spiritual significance. Despite these efforts, sacred places face threats from urbanization, resource exploitation, and severe weather events that disrupt traditional activities.

Through collaborative partnerships with universities and government agencies, indigenous communities are reclaiming their rightful role as guardians of ancestral landscapes and heritage.

Frequently Asked Questions

How Did Ancient Native Americans Engineer Water Systems for Their Settlements?

You’ll find indigenous engineers developed gravity-fed irrigation techniques through canals, reservoirs sealed with clay, and filtration systems. Their sophisticated water management included tidal watercourts and adaptive designs for diverse environments.

What Tools Were Used to Create Massive Earthworks Without Modern Technology?

You’d find ancient tools like digging sticks, stone scrapers, and bone implements used with basic earthwork techniques: manual excavation, basket transport, and layered soil construction requiring massive coordinated labor forces.

How Did Climate Change Affect Pre-Columbian Settlement Patterns?

Picture vast abandoned cities, parched under relentless sun. You’ll observe that dramatic climate shifts during 950-1450 CE directly shaped migration patterns, causing population aggregation during wet periods and forced abandonment during prolonged droughts.

What Evidence Exists of Trade Networks Between Distant Native American Cultures?

You’ll find extensive evidence in copper artifacts traded 1,500 km between Great Lakes and Southeast, turquoise networks connecting Southwest Puebloans with distant regions, and Columbia River cultural exchanges facilitated by specialized trade languages.

How Did Astronomical Knowledge Influence Settlement Design and Orientation?

You’ll find celestial navigation embedded in Native American settlements through architectural alignment with solstices, cardinal directions, and lunar cycles—orienting plazas, mounds, and observation points to track seasons and connect with cosmic order.

References

- https://www.floridastateparks.org/parks-and-trails/crystal-river-archaeological-state-park

- https://www.crazycrow.com/site/resources/native-american-historic-sites/

- https://www.infoplease.com/history/native-american-heritage/american-indian-archaeological-sites

- https://www.wilderness.org/articles/article/10-extraordinary-native-american-cultural-sites-protected-public-lands

- https://cahokiamounds.org

- https://historicsites.nc.gov/all-sites/town-creek-indian-mound

- https://www.nps.gov/subjects/travelamericancultures/amindsites.htm

- https://historyguild.org/interesting-stories-of-the-mound-building-native-american-civilizations-of-the-midwest/

- https://www.thearchcons.org/bookreviews/the-mound-builders/

- https://mdcinc.org/2022/08/04/ocmulgee-mounds-indigenous-earthworks-in-the-southeast-and-mound-power/