America’s most significant archaeological sites include abandoned Native American settlements across the Southwest. You’ll discover Ancestral Puebloan ruins like Mesa Verde’s cliff dwellings, with their innovative T-shaped doorways and ceremonial kivas. These settlements, mysteriously abandoned around 1300 CE, reveal sophisticated engineering and sustainable agricultural practices. Unlike mining boomtowns, these communities thrived for generations before environmental challenges forced migration. The silent stones continue to whisper stories of cultural resilience and complex human-environment relationships.

Key Takeaways

- Mesa Verde National Park contains well-preserved cliff dwellings built between 1150-1200 CE that were mysteriously abandoned around 1300 CE.

- Ancestral Puebloan sites across the Southwest feature innovative architecture including T-shaped doorways, ceremonial kivas, and sophisticated multi-story structures.

- Environmental challenges like drought, resource depletion, and climate change likely contributed to the abandonment of many Native American settlements.

- Rock art at abandoned sites provides insights into cultural development, territorial boundaries, and migration routes spanning up to 6,000 years.

- Unlike mining ghost towns, Native American abandoned settlements reflected generations of sustainable habitation before environmental pressures forced migration.

The Ancient Puebloan Legacy: America’s Original Ghost Towns

What remarkable testimony to human ingenuity lies scattered across the Four Corners region of the American Southwest?

You’ll find hundreds of Ancestral Puebloan sites spanning Colorado, Utah, Arizona, and New Mexico—with evidence extending into Nevada, Texas, and northern Mexico.

These settlements, abandoned around 1300 A.D., represent sophisticated cultural resilience through architectural innovation.

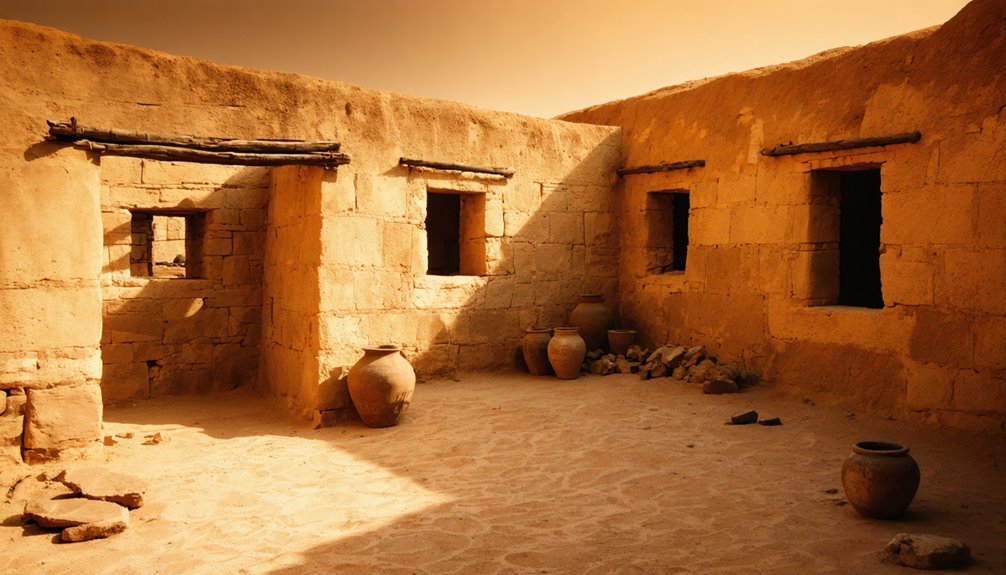

Abandoned Puebloan dwellings showcase a civilization’s ability to thrive through ingenious building techniques despite harsh desert conditions.

From Cliff Palace at Mesa Verde to the submerged Pueblo Grande de Nevada, these communities featured distinctive T-shaped doorways, strategic corner windows, and ceremonial kivas.

Their ancestral agriculture systems supported substantial populations through meticulously organized storage rooms for corn, beans, and squash. These remnants provide valuable archaeological insights into their rich cultural artifacts and daily life.

Ancestral Puebloans evolved from the earlier Basketmaker culture who constructed underground pit-houses with roofs made of brush, planks and earth around 300 A.D.

While many sites remain accessible at national parks like Chaco Culture and Mesa Verde, others lie hidden, awaiting rediscovery—silent witnesses to a civilization that mastered desert survival for centuries.

Mesa Verde National Park: Cliff Dwellings Frozen in Time

When you visit Mesa Verde’s cliff dwellings today, you’re witnessing the remarkable architectural achievements of Ancestral Puebloans who crafted multi-story structures from sandstone and adobe that have withstood eight centuries of harsh Colorado weather.

These ingeniously designed communities, built between 1150-1200 CE, feature circular kivas for ceremonies, interconnected living spaces, and strategic placement within protective alcoves that sheltered inhabitants from both elements and potential threats. The most impressive dwelling, Cliff Palace, contains over 150 rooms and 21 kivas, serving as an important ceremonial and administrative center for the ancient community. The discovery of this magnificent structure occurred in 1888 when two ranchers stumbled upon it while searching for their missing cattle.

Despite their sophisticated engineering and adaptation to the environment, these elaborate settlements were mysteriously abandoned around 1300 CE, likely due to a combination of prolonged drought, resource depletion, and environmental pressures that continue to intrigue archaeologists.

Ancient Engineering Marvel

Nestled within the sandstone cliffs of southwestern Colorado, Mesa Verde’s cliff dwellings represent one of North America’s most sophisticated pre-Columbian architectural achievements.

As you explore Cliff Palace, you’ll witness the ingenuity of ancient architecture featuring 150 rooms and 20+ kivas arranged around communal plazas.

The Ancestral Puebloans mastered their environment by incorporating natural alcoves into their designs, crafting multi-story structures using sandstone blocks and wooden beams without arches or pillars.

Their engineering exploited cliff shelves for protection while creating ceremonial structures like subterranean kivas with specialized ventilation systems and firepits.

These dwellings housed approximately 100 people in family-based units, reflecting a complex social organization that balanced daily living with religious practice. Vibrant painted murals adorned many interior walls, featuring geometric patterns and natural imagery derived from mineral-based pigments.

The strategic locations provided security through limited access points—a reflection of their practical and ceremonial ingenuity.

Since their abandonment around 1300 CE, these remarkable structures have endured centuries of exposure, requiring constant maintenance to preserve their historical integrity.

Weathering Environmental Extremes

The precarious existence of Mesa Verde’s cliff dwellings within their sandstone alcoves reveals a perpetual battle against environmental forces that continually reshape these architectural treasures.

You’ll witness the complex interplay of geological composition and climate creating both protection and peril for these structures. Weathering processes accelerate as climate change intensifies freeze-thaw cycles, driving moisture into sandstone cracks that expand upon freezing. Park officials have implemented fuel breaks to mitigate growing wildfire threats that endanger these irreplaceable structures. Ancestral Puebloans abandoned these remarkable structures in the late 13th century due to the Great Drought that devastated their agricultural systems.

- Freeze-thaw action wedges apart cliff faces, threatening structural integrity

- Wildfires expose hidden archaeological sites while endangering wooden components

- Variable precipitation in this semi-arid environment creates unpredictable erosion patterns

- Underlying shale layers expand when wet, causing terrain instability

The environmental resilience of these dwellings testifies to ancestral Puebloan engineering wisdom, yet modern intervention becomes increasingly necessary as climate extremes intensify beyond historical precedents.

Abandonment Mystery Endures

Despite extensive archaeological research spanning more than a century, the abrupt abandonment of Mesa Verde‘s magnificent cliff dwellings around 1300 C.E. remains one of North America’s most compelling prehistoric mysteries.

As you explore these ancient structures, you’ll encounter competing abandonment theories that challenge your understanding of societal collapse. Was it prolonged drought that devastated agricultural systems? Did overpopulation strain limited resources beyond sustainability? Perhaps defensive concerns or shifting religious imperatives compelled the Ancestral Puebloans to seek new horizons.

Environmental impacts likely played a vital role—the combination of declining rainfall, depleted soil fertility, and overexploited natural resources created untenable living conditions.

Most scholars now favor a multi-causal explanation rather than seeking a single decisive factor. The evidence suggests these indigenous architects responded rationally to deteriorating conditions, making a deliberate choice to migrate rather than face extinction.

Stargazing Among Ruins: Chaco Canyon’s Dual Heritage

When you visit Chaco Canyon today, you’ll witness the culmination of Ancestral Puebloan astronomical expertise etched into rock, aligned in architecture, and preserved in the dark skies above.

The site’s famous “Sun Dagger” petroglyph and precisely oriented structures demonstrate sophisticated celestial knowledge that regulated agricultural cycles and spiritual ceremonies across generations.

Chaco’s designation as an International Dark Sky Park now protects the same starry canvas that guided its ancient inhabitants, offering you a rare window into Indigenous astronomical traditions that span millennia. Situated in the arid San Juan Basin, the park’s limited annual rainfall of approximately 8-9 inches contributed to both the excellent preservation of archaeological sites and the eventual abandonment of this once-thriving cultural center.

The extensive network of ceremonial roads radiating from great houses suggests these paths may have served as sacred routes for pilgrims traveling to this cultural center for spiritual gatherings.

Celestial Observation History

Ancient Chacoan architects engineered their ceremonial structures with remarkable astronomical precision, creating what scholars now recognize as one of North America’s most sophisticated celestial observation networks.

Between 850-1150 AD, you’ll find evidence of celestial alignments governing everything from building placement to road construction across 5,000 square kilometers of landscape. These astronomical rituals connected distant communities through shared observations of solar and lunar cycles.

Four key elements of Chaco Canyon’s astronomical system:

- The Sun Dagger petroglyph that precisely marks solstices and equinoxes

- Buildings oriented to track lunar standstill cycles occurring every 18.6 years

- The Great North Road deliberately aligned with true celestial north

- Multiple observation sites allowing simultaneous viewing of astronomical events by ceremonial officials

Ancestral Astronomical Knowledge

Because celestial phenomena dictated nearly every aspect of community life, Chaco Canyon’s ancestral architects embedded profound astronomical knowledge within their monumental structures and cultural landscape.

You’ll find buildings precisely oriented to mark solstices and equinoxes, with corner windows capturing winter solstice sunrises and spiral petroglyphs recording solar positions.

Walking the canyon today, you’re traversing an ancient cosmic map. The twelve major structures correspond to solar and lunar cycles, while observation points like Wijiji ledge allowed priests to predict celestial events weeks in advance.

The Great North Road and ritual kivas form part of a complex system that synchronized agricultural practices with ceremonial rhythms.

These celestial alignments weren’t merely practical—they expressed the deep cosmological significance of a worldview where the heavens, earth, and human experience existed in sacred harmony.

Night Sky Preservation

While the ancient structures of Chaco Canyon preserve humanity’s historical connection to the cosmos, the park’s modern designation as an International Dark Sky Park guarantees this celestial relationship continues uninterrupted.

Receiving Gold-tier recognition, Chaco commits to protecting nocturnal ecosystems from light pollution through carefully designed illumination policies.

When you visit, you’ll experience:

- One of America’s darkest night skies where 99% of the park maintains natural darkness

- Wildlife thriving in their natural nocturnal rhythms, undisturbed by artificial light

- The Chaco Observatory’s specialized programs connecting ancient and modern astronomy

- A rare opportunity to witness celestial phenomena as the Ancestral Puebloans did centuries ago

The park’s pioneering approach to darkness preservation represents both ecological stewardship and the liberation of natural cycles from modern encroachment.

Beyond the Tourist Trail: Hidden Archaeological Treasures

Far beyond the well-trodden paths of mainstream tourism lie America’s hidden archaeological treasures—sites that reveal the rich tapestry of Native American history yet remain largely unknown to casual visitors.

You’ll discover extraordinary hidden histories at places like the Miami Circle National Historical Landmark in Florida, where the Tequesta people created a unique rock-cut structure over 2,500 years ago.

In Nevada, Grimes Point showcases millennia-old petroglyphs, while Hidden Cave served ancient peoples as storage areas.

Utah’s Parowan Gap contains over 1,500 rock carvings of profound cultural significance to modern Paiute and Hopi tribes.

These sites face ongoing preservation challenges, with many requiring protection from looting and vandalism.

Interpretive trails offer balanced access—allowing you to experience these archaeological wonders while ensuring their survival for future generations.

Reading the Rocks: Decoding Ancient Messages in Canyon Country

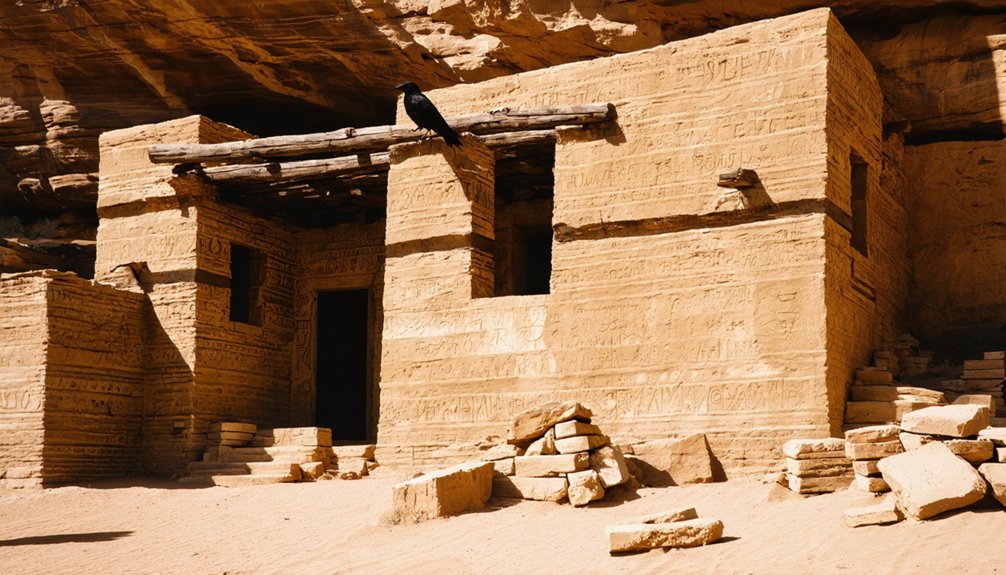

Throughout the sandstone canyons and desert landscapes of the American Southwest, ancient Native Americans left behind a complex visual language etched and painted onto stone surfaces.

These petroglyphs and pictographs offer profound insights into cultures spanning thousands of years, with rock symbols conveying societal values and spiritual beliefs.

When deciphering these messages, you’ll encounter:

- Repetitive motifs like anthropomorphic figures and handprints suggesting intercultural communication

- Chronological layering revealing up to 6,000 years of continuous cultural development

- Geographic distribution patterns indicating territorial boundaries and migration routes

- Symbolic imagery representing hunting magic, cosmological concepts, and shamanic practices

The cultural significance extends beyond mere artistic expression—these sites function as ancestral texts requiring interdisciplinary analysis.

Ancient rock art transcends decoration, serving as complex narratives that speak through generations of indigenous knowledge.

Little Petroglyph Canyon’s 20,000+ images and Nine Mile Canyon’s extensive panels demonstrate the sophisticated communication systems of peoples who understood freedom through their relationship with the land.

Preservation Challenges: Balancing Access and Protection

Despite decades of preservation efforts, Native American ghost towns and cultural sites face an unprecedented convergence of threats that challenge their long-term survival. Rising sea levels, severe flooding, and harsh weather conditions accelerate deterioration while a $12 billion maintenance backlog hampers vital restoration work.

You’ll find the most vulnerable sites lack formal recognition, particularly indigenous locations with profound cultural significance. These places suffer from regulatory gaps that enable development and vandalism while budget constraints make demolition economically preferable to protection.

Implementing sustainable tourism practices requires balancing public access with preservation. When visiting these sacred spaces, cultural sensitivity is essential—the narratives presented often obscure indigenous histories through whitewashed accounts.

True preservation must center tribal voices while addressing both environmental threats and the infrastructure strain caused by increasing visitation.

Native Settlements vs. Mining Boomtowns: A Cultural Comparison

When examining ghost towns across the American landscape, you’ll discover fundamental differences between Native American settlements and mining boomtowns that reflect contrasting worldviews and relationships with the land.

These distinctions illuminate divergent approaches to community building and sustainability:

Understanding ghost towns requires examining how fundamentally different cultural values shaped community resilience and relationship to place.

- Origin purpose – Native settlements established for generations of habitation versus boomtowns created solely for resource extraction.

- Economic sustainability – Diverse subsistence activities in Native communities versus single-resource dependence in mining towns.

- Population stability – Multi-generational Native communities versus transient boomtown populations.

- Cultural resilience – Native towns maintained traditions and governance systems over centuries, while boomtowns lacked established social infrastructure.

These contrasts help explain why many Native settlements persisted through challenges that rapidly collapsed mining communities, demonstrating fundamentally different approaches to human-environment relationships and community development.

Frequently Asked Questions

What Indigenous Foods Can Visitors Forage Near Archaeological Sites?

You shouldn’t forage at archaeological sites, as it’s typically illegal. Indigenous foraging techniques once harvested pinyon nuts, mesquite beans, chenopod seeds, prickly pear fruit, and wild berries near these protected areas.

Are Overnight Ceremonies or Spiritual Retreats Permitted at These Locations?

You can’t access overnight ceremonies or spiritual retreats without explicit tribal authorization. Ceremonial permissions vary by location, with most spiritual practices requiring advance approval from sovereign Indigenous authorities.

How Do Current Pueblo Tribes Connect With Their Ancestral Sites?

You’ll find Pueblo tribes maintain ancestral connections through ceremonial practices, political advocacy, collaborative research, and implementing protective measures—all while integrating traditional knowledge with scientific approaches for cultural preservation and sovereignty.

What Restoration Techniques Are Used to Maintain Crumbling Structures?

You’ll find structural assessment, traditional material restoration, community knowledge integration, and adaptive preservation forming the core restoration methods. These techniques address preservation challenges while maintaining authenticity and historical integrity in deteriorating Native American structures.

Can Visitors Collect Pottery Shards or Artifacts as Souvenirs?

No, you cannot collect artifacts. Legal restrictions under NAGPRA and ARPA prohibit artifact removal, with penalties including imprisonment and fines. Preservation of these cultural materials respects tribal heritage and archaeological integrity.

References

- https://www.notesfromthefrontier.com/post/untitled

- https://www.christywanders.com/2024/08/top-ghost-towns-for-history-buffs.html

- https://nicenews.com/culture/ghost-towns-across-america/

- https://www.scmp.com/lifestyle/travel-leisure/article/3254037/ultimate-us-ghost-towns-exploring-ancient-native-americans-settlements-and-culture-and-camping-under

- https://www.gilahot.com/ghost_towns.shtml

- https://www.visitutah.com/things-to-do/history-culture/ghost-towns

- https://familytraveller.com/usa/national-parks/american-west-ghost-towns/

- https://www.newmexico.org/places-to-visit/ghost-towns/

- https://www.legendsofamerica.com/ghost-towns/

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qBnO4_-RmAw