New Mexico’s ghost towns transport you to the Wild West through over 400 abandoned settlements. You’ll discover well-preserved Chloride with 27 original structures, infamous Loma Parda (once “Sodom on the Mora”), and White Oaks, which transformed from cattle frontier to a booming city after the 1879 gold discovery. These sites showcase cultural influences from Puebloan, Spanish, and American settlers. Each abandoned town reveals unique stories of prosperity, tragedy, and frontier resilience.

Key Takeaways

- White Oaks transformed from cattle frontier to New Mexico’s second-largest city after gold discovery in 1879.

- Chloride is the best-preserved frontier town with 27 original structures including Pioneer Store Museum and Monte Cristo Saloon.

- Mogollon produced 70% of New Mexico’s precious metals by 1909, extracting approximately 18 million ounces of silver.

- Dawson’s coal mining history is marked by two devastating explosions in 1913 and 1923, claiming 384 lives.

- Ghost towns like Golden along the Turquoise Trail preserve Spanish colonial and mining architecture from the 1800s.

The Gold Rush Legacy of White Oaks

While the Wild West’s history is often dominated by tales of outlaws and lawmen, the story of White Oaks exemplifies how gold discoveries transformed frontier settlements into thriving communities.

When John Wilson, Jack Winters, and Harry Baxter struck gold in 1879 in the Jicarilla Mountains, they sparked a transformation that would turn this cattle frontier into New Mexico’s second-largest city.

As you explore this historic ghost town, you’ll discover the legacy of major operations like the Old Abe Mine, which produced up to 50 tons of gold ore daily.

White Oaks’ gold mining prosperity supported 50 businesses and 4,000 residents at its peak, including an opera house and four newspapers.

The town’s distinctive Victorian architecture stands as evidence of the wealth that flowed before economic decline and resource exhaustion led to abandonment.

Local miners became wealthy overnight when they sold their Homestake Mine and South Homestake Mine claims for $300,000 each.

The town’s eventual decline can be attributed to the high land prices demanded by local property owners that prevented crucial railroad expansion into White Oaks.

Sodom on the Mora: Loma Parda’s Notorious Past

When Fort Union was established in 1851, the quiet farming village of Loma Parda transformed into one of New Mexico Territory’s most notorious destinations.

Nicknamed “Sodom on the Mora,” this once-agricultural community rapidly expanded with saloons, brothels, and gambling halls catering to soldiers, cowboys, and desperados traveling the Santa Fe Trail.

The sin city of frontier New Mexico, where saloons and brothels replaced corn fields to serve thirsty trailblazers.

You’ll find Loma Parda’s history filled with violence and lawlessness—from vigilante justice to scandalous kidnappings. The small village’s population exploded from around 500 residents to become one of the largest settlements in the region. Commanding officers repeatedly declared the town off-limits to soldiers, but these orders were routinely ignored.

Captain Sykes famously punished prostitutes by shaving their heads, creating the legend of “Baldwomen’s Canyon.” The vice industries thrived until Fort Union’s closure in 1889, when the town lost its primary patrons.

Today, only crumbling walls remain where raucous establishments once stood.

This ghost town serves as a stark reminder of how quickly a place can rise and fall with changing frontier economies.

Golden: Where History Lives Along the Turquoise Trail

When you visit Golden along the Turquoise Trail, you’ll encounter Henderson’s Historic Treasures, including remnants of the first gold rush west of the Mississippi that began in 1825.

You can examine the well-preserved San Francisco de Assis Catholic Church, built around 1830, which continues to serve as an active place of worship with weekly Mass. The church stands as a testament to the religious foundations established during the area’s mining camp era.

Golden’s Sacred Heritage reflects the layered cultural influences of Puebloan peoples, Spanish colonists, and American settlers who shaped this mining community before it evolved into the ghost town you see today. The town was originally known as Real de San Francisco before changing its name to Golden around 1880.

Henderson’s Historic Treasures

Located along the historic Turquoise Trail National Scenic Byway, Golden stands as a symbol to New Mexico’s rich mining heritage.

You’ll discover Henderson’s Artifacts throughout this former boomtown, which sparked the first gold rush west of the Mississippi in 1825—predating both California and Colorado’s famous rushes.

The San Francisco de Assis Church, built around 1830 and restored in the 1960s, remains active today, serving as a representation of the town’s enduring spirit.

Henderson’s Legends include tales of the shift from Native American turquoise mining dating back to 900 AD to the industrial gold operations that established the town by 1879. Like nearby Madrid, which transformed from a coal mining town into an artistic community following the coal market collapse in the 1950s, Golden has reinvented itself as a historical destination.

While the population declined as ore depleted, Golden’s preserved structures now attract visitors seeking authentic Wild West history along this 65-mile scenic route from Tijeras to Santa Fe. The area’s distinctive blue turquoise has been mined for over 1,000 years and remains an important cultural touchstone for both residents and tourists.

Golden’s Sacred Heritage

Deeply rooted in spiritual tradition, Golden’s sacred heritage begins with the San Francisco de Assis Church, a structure that has stood as the town’s spiritual anchor since approximately 1830.

You’ll find this historic landmark restored by Fray Angelico Chavez in the 1960s, now serving as a focal point for the community’s sacred traditions.

When you visit Golden, you’ll witness how mining heritage and spirituality intertwine. Originally called Real de San Francisco after an 1825 gold discovery that sparked the first gold rush west of the Mississippi, the town preserves both its Catholic and indigenous cultural elements.

The annual Fiesta de San Francisco de Assis exemplifies this blend, featuring Matachines dancers, grave blessings, and community celebration.

As you explore, you’ll discover that the church and adjacent cemetery remain essential sacred spaces in this once-booming mining community. The area is easily accessible via the Turquoise Trail Scenic Byway, offering visitors breathtaking views along the journey.

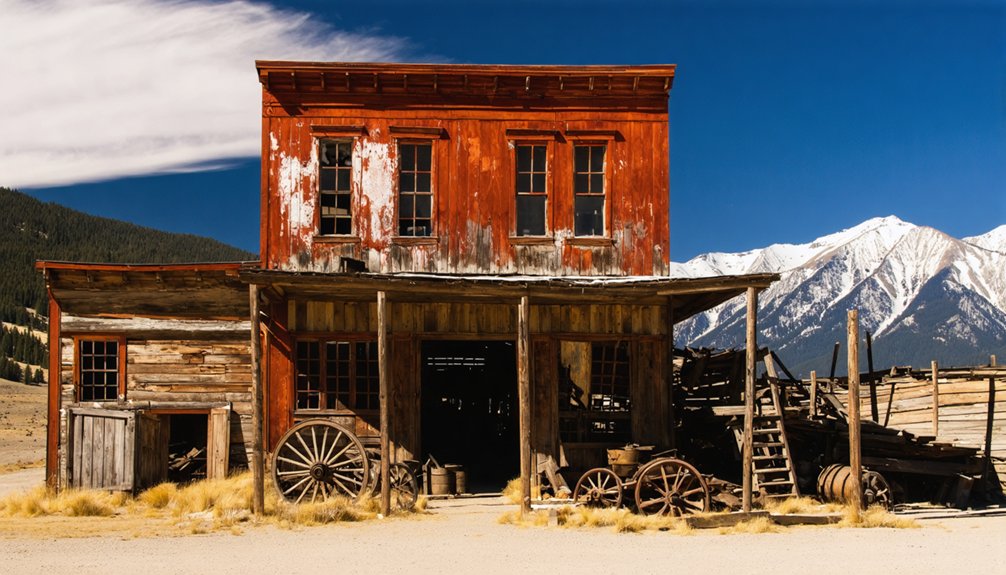

Chloride: The Best-Preserved Frontier Town

Among New Mexico’s ghost towns, Chloride stands as the most remarkably preserved frontier settlement, offering visitors an authentic glimpse into 1880s mining life.

This silver mining town originated in 1879 when Harry Pye, an English mule skinner, accidentally discovered silver chloride ore while traversing Apache territory. His claim in 1881 triggered a mining rush despite dangerous Apache raids.

At its peak, Chloride boasted 1,000-3,000 residents with over 100 homes and numerous businesses—from saloons to a Chinese laundry. The town even formed a 51-member militia in 1884 for protection against Apache attacks. The town was originally called Pyetown and Bromide before officially becoming Chloride.

When silver prices collapsed in the 1890s, Chloride’s boom ended. Today, you’ll find 27 original structures including the Pioneer Store Museum and Monte Cristo Saloon, preserved monuments to this frontier community’s resilience.

Mining Heritage in Mountain-Nestled Mogollon

In the high elevations of the Mogollon Mountains, you’ll encounter a remarkable ghost town that once produced 70% of New Mexico’s precious metals by 1909.

The architectural evolution of Mogollon reflects its tumultuous history, with buildings reconstructed multiple times in increasingly fire-resistant materials following devastating blazes in 1894, 1904, 1910, 1915, and 1942.

Your exploration through this former boomtown, which fluctuated between 3,000 and 6,000 residents during its 1890s heyday, offers a glimpse into the challenging life of miners who extracted approximately 18 million ounces of silver while battling harsh mountain conditions and occupational hazards like black lung disease.

Mountain Mining Architecture

The rugged slopes of the Gila Wilderness cradle Mogollon, a tribute to mining ingenuity nestled within Silver Creek Canyon‘s challenging terrain. As you explore, you’ll notice how Mogollon architecture evolved from primarily wooden structures to stone and adobe buildings after recurring fires swept through the settlement.

The town’s practical design reflects miners’ priorities—simple, utilitarian buildings with minimal ornamentation dot the canyon, following Silver Creek’s natural path. Mine structures, including headframes and processing mills, were strategically built into mountainsides to utilize gravity for ore transport.

Original buildings dating to the 1890s still stand, showcasing mining techniques through timber-framed structures with metal reinforcements.

The National Register of Historic Places recognized Mogollon’s significance in 1987, preserving this authentic glimpse into mining heritage where industrial innovation met wilderness constraints.

Gold Rush Boom Days

Sergeant James Cooney’s 1870 discovery of gold and silver deposits marked the beginning of Mogollon’s transformation from wilderness to boomtown.

Though initially kept secret, his return in 1876 launched extensive Mogollon mining operations that eventually produced nearly $20 million in precious metals, with silver production accounting for two-thirds of this wealth.

During your exploration of this Wild West legacy, you’ll encounter:

- The Little Fannie Mine, which operated 24/7 at its peak

- Sites where over 18 million ounces of silver were extracted, representing one-quarter of New Mexico’s total silver output

- Remains of infrastructure that survived five major fires and four devastating floods

- Historic freight routes where 18-horse teams once hauled ore along treacherous 80-mile paths to Silver City

Preserved Gila Forest Setting

Nestled deep within the rugged Mogollon Mountains, the historic mining settlement of Mogollon rests in a pristine pocket of the Gila National Forest, where dense coniferous woods envelop what remains of this once-thriving boomtown.

As you explore, you’ll notice how the Gila ecology has gently reclaimed portions of the town while preserving its essence. Silver Creek Canyon’s remote terrain—while challenging for early miners—now serves as a natural museum protecting remnants of Mogollon architecture.

About 100 historic structures survive, including the remarkable two-story adobe Silver Creek Inn (circa 1885). The town’s placement on the National Register of Historic Places in 1987 guarantees these treasures remain intact for your discovery.

Though periodic floods from mountain snowmelt have threatened the settlement, this isolation has paradoxically preserved Mogollon’s authentic character against modern intrusions.

Dawson’s Tragic Mining Legacy

Tragedy stalked the coal mines of Dawson, New Mexico, where two devastating explosions in 1913 and 1923 claimed 384 lives and forever marked the town’s legacy in American industrial history.

As you explore this ghost town, you’ll encounter the haunting remnants of a once-thriving community where Phelps Dodge Corporation built a company town to support its lucrative coal operations.

The Dawson disasters highlight industrial America’s painful evolution toward mining safety:

- The 1913 explosion killed 261 miners after an unsafe dynamite detonation.

- The 1923 tragedy took 123 lives when a derailed mine car created fatal sparks.

- Distinctive white iron crosses still mark miners’ graves in Dawson Cemetery.

- These catastrophes occurred despite Dawson’s reputation as a modern mining town.

Ghost Town Photography: Capturing the Past

When photographing ghost towns in New Mexico, you’ll need specialized equipment and techniques to properly document these abandoned historical sites. A sturdy tripod is essential for the long exposures (15-30 seconds) required in low-light conditions, while wide-angle lenses (14-30mm) create compelling ghost town aesthetics by emphasizing emptiness and architectural depth.

Arrive at dawn or dusk when soft, directional light enhances textures and shadows. Focus on photographic storytelling by capturing both sweeping vistas of main streets and intimate details of artifacts—bottles, tools, furniture—that speak to former inhabitants’ lives.

Employ manual focus with ISO 1600+ for dark interiors, and bracket exposures to handle extreme contrast. Don’t forget your headlamp for guiding safely, and research property access restrictions beforehand to avoid legal complications.

Planning Your Ghost Town Road Trip

While capturing the perfect ghost town photograph preserves memories of your adventure, thoughtful planning beforehand guarantees a successful exploration.

New Mexico’s 400+ ghost towns require strategic route planning, with accessibility varying considerably across regions. Consider clustering your visits along major highways like I-40 or historic Route 66, where towns like Glenrio and Cuervo await discovery.

- Assess vehicle requirements – Many destinations require unpaved travel; verify your vehicle has adequate ground clearance for backcountry byways.

- Time your visit strategically – Spring and fall offer prime conditions; avoid summer heat and winter snow.

- Plan for isolation – Carry emergency supplies and notify someone of your itinerary.

- Research ownership status – Respect private property boundaries and heed safety warnings about structurally compromised buildings.

Preservation Efforts and the Future of New Mexico’s Ghost Towns

As New Mexico’s ghost towns stand frozen in time, preservation efforts have emerged as critical safeguards against their complete disappearance. You’ll find organizations like the New Mexico Historic Preservation Division collaborating with local groups to protect these fragile historical sites.

The Edmund family in Chloride and the Shakespeare Foundation exemplify successful grassroots preservation, transforming ruins into educational destinations.

However, significant preservation challenges persist. Modern mining operations threaten historic integrity, with Summa Silver’s exploratory drilling near Mogollón Cemetery raising concerns.

Limited resources hamper small preservation groups, while harsh desert conditions accelerate structural deterioration. These sites hold immense cultural significance as tangible connections to frontier life, requiring a delicate balance between tourism access and protecting their authentic character for future generations.

Frequently Asked Questions

Are There Paranormal Investigations or Ghost Tours Available?

Despite skepticism, you’ll find numerous ghost hunting opportunities at haunted locations like Dawson, Las Cruces’ Dona Ana County Courthouse, and Bonito Lake, with both guided tours and specialized paranormal investigation experiences available.

How Accessible Are These Towns for Visitors With Mobility Limitations?

Most ghost towns offer limited wheelchair access due to rugged terrain and crumbling infrastructure. You’ll encounter uneven surfaces, minimal parking availability, and few accessibility modifications that preserve historical authenticity while accommodating mobility limitations.

What Camping Options Exist Near These Ghost Towns?

Under the vast star-speckled canopy, you’ll find diverse camping options: dispersed BLM sites with minimal campground amenities, RV facilities requiring Harvest Hosts membership, and forest camping—all subject to specific camping regulations near ghost towns.

Can Visitors Legally Collect Artifacts From These Historic Sites?

No, you can’t legally collect artifacts from ghost towns on federal lands. Legal regulations strictly prohibit removal of historic items, supporting artifact preservation as these resources are nonrenewable and protected by law.

What Wildlife Hazards Should Visitors Be Aware Of?

Be vigilant, be prepared, be cautious. You’ll encounter venomous snakes, predatory mammals, and poisonous arthropods. Effective wildlife safety requires sturdy boots, secure food storage, and visitor precautions like checking crevices and making noise while hiking.

References

- https://compaslife.com/blogs/journal/abandoned-enchantment-ghost-towns-of-new-mexico-1

- https://newmexicotravelguy.com/new-mexico-ghost-towns/

- https://www.atlasobscura.com/things-to-do/new-mexico/ghost-towns

- https://www.tripadvisor.com/Attractions-g28952-Activities-c47-t14-New_Mexico.html

- https://newmexiconomad.com/category/history/new-mexico-ghost-towns/

- https://www.newmexicoghosttowns.net/counties

- https://www.newmexicomagazine.org/blog/post/abandoned-ghost-towns-new-mexico/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_ghost_towns_in_New_Mexico

- https://www.newmexico.org/places-to-visit/ghost-towns/map/

- https://www.legendsofamerica.com/nm-whiteoaks/