You’ll find Ferguson, Oklahoma’s ghost town roots in its 1881 founding by Chicago businessmen Francis Beidler and Benjamin Ferguson as a lumber operation. The settlement evolved into a thriving all-Black community with modern amenities, churches, and schools, providing refuge from Jim Crow laws. While the town declined due to resource depletion and railroad rerouting, its scattered ruins and weathered markers tell a powerful story of African American achievement and determination in the American West.

Key Takeaways

- Ferguson was founded by Chicago businessmen Francis Beidler and Benjamin Ferguson as a logging industry hub in Oklahoma Territory.

- The town operated as an all-Black community with churches, schools, and strong economic independence during racial segregation.

- Agricultural activities centered on cotton and corn production, utilizing the Canadian River valley’s rich soil.

- Community life thrived around churches and schools, fostering cultural celebrations and educational growth despite segregation challenges.

- The town’s decline occurred due to resource depletion, railroad rerouting, and youth migration, leaving only scattered ruins today.

Origins and Early Settlement

While the available historical records point to multiple Ferguson ghost towns across America, the Oklahoma settlement originated through different circumstances than its South Carolina namesake.

Two Chicago businessmen, Francis Beidler and Benjamin Ferguson, established the town as a self-contained logging industry hub, strategically positioned to exploit the region’s virgin forests.

Shrewd Chicago industrialists Beidler and Ferguson founded a remote logging settlement to harvest the untouched wilderness for profit.

You’ll find that Ferguson’s early development reflected the post-Civil War industrial boom, when Eastern and Midwestern timber resources were becoming depleted.

The founders designed the settlement for complete community isolation, building it with modern amenities including indoor plumbing and gas lighting.

Similar to how oil discovery transformed Webb City in 1922, the Santee River Cypress lumber operation became central to the town’s identity in 1881.

The town featured sawmills, kilns, and housing for 350 workers and their families.

A unique economic system using company scrip kept workers tethered to the town’s internal economy through the company store.

Life in an All-Black Town

In Ferguson’s all-Black community, you’d find daily life centered around essential gathering places like churches and schools where African American teachers educated local children.

Your family could rely on strong support networks that developed through shared community events, religious services, and social activities connecting multiple households.

You’d witness how these institutional and familial bonds created stability, allowing residents to maintain their economic independence while fostering cultural pride and educational advancement despite the broader context of segregation in Oklahoma Territory. Neighbors regularly provided financial assistance and markets to help each other maintain viable farming operations and businesses. The town served as a safe haven from racial discrimination and violence that many African Americans faced in the South.

Daily Community Activities

Life in Ferguson flowed with remarkable self-sufficiency through its extensive network of Black-owned enterprises and community institutions.

You’d find daily routines centered around farming activities, with families working their allotted lands while supporting local cotton gins and markets. At the nationally chartered Black-owned bank, you’d handle your finances alongside fellow entrepreneurs running stores and newspapers. For many residents, economic advancement and self-help were driving principles that shaped their business decisions.

Community gatherings became the heartbeat of social life, where you’d participate in town meetings, Masonic lodge events, and cultural celebrations. Following annual traditions, families would gather to enjoy the exciting Black rodeo events that showcased local talent and heritage.

You’d share resources through agricultural cooperatives and mutual aid societies, strengthening bonds between neighbors. The railroad station buzzed with activity as you’d trade goods, welcome newcomers, and connect with the wider world.

Modern amenities like electricity and running water made daily life more comfortable than in many surrounding areas.

Church and School Life

Churches and schools formed the bedrock of Ferguson’s social fabric, creating an intricate support system that nurtured both spiritual and educational growth. You’d find church gatherings serving multiple purposes, from Sunday services to political meetings, while educational programs thrived despite segregation laws. As in other All-Black towns, Ferguson’s institutions provided refuge from the discrimination of Jim Crow. The community struggled to maintain these vital institutions during the Great Depression years, when economic hardship threatened their survival.

Local teachers and clergy worked together to build a resilient community, sharing resources and facilities to maximize their impact.

- Church buildings doubled as community centers for cultural events and social gatherings

- Educational programs included literacy classes, vocational training, and agricultural instruction

- Sunday schools complemented formal education, reinforcing community values

- Joint church-school festivals and homecomings celebrated African American heritage

- Both institutions fostered future leaders who’d advocate for civil rights

These pillars of Ferguson’s society helped you resist discrimination while preserving cultural identity and promoting social advancement through mutual support and shared determination.

Family Support Networks

Strong family bonds formed the cornerstone of Ferguson’s resilient community, where multiple generations lived and worked together to create a self-sustaining haven from racial oppression.

You’d find extended families living in close proximity, sharing resources and responsibilities across household lines. Family resilience manifested through informal caregiving networks, where neighbors helped raise children and support elders.

This mutual aid system went beyond immediate family, creating a web of support that touched every aspect of daily life.

You’d see community members pooling resources during hard times, sharing farm labor, and providing emergency assistance when needed.

These family networks preserved cultural traditions and oral histories, passing down not just practical skills but also the essential narrative of liberation that had brought their ancestors to Ferguson in search of independence.

Canadian River Community

Along the winding Canadian River, Ferguson emerged as a significant African-American settlement in 1901, establishing itself roughly 12 miles north of Watonga in Blaine County. French explorers were among the first Europeans to document and map this vital waterway in the early 1700s.

You’ll find this historic waterway served as more than just river navigation – it was a crucial boundary marking historical borders between territories and nations, including the northern edge of the Choctaw Nation following the 1820 Treaty of Doak’s Stand. Rising in the Sangre de Cristo Mountains, the river carved deep canyons and valleys that shaped settlement patterns throughout the region.

- The Canadian River acted as a natural highway for Native Americans and early explorers

- African Lighthorsemen and Cherokee Freedmen maintained strong connections to the area

- The river’s strategic importance made it contested during the Civil War

- Local communities reflected a rich blend of African American and Native American heritage

- The river corridor fostered cultural exchange between diverse ethnic groups before Oklahoma statehood

Agricultural Heritage

You’ll find Ferguson’s agricultural legacy deeply rooted in cotton and corn production, with farmers capitalizing on the rich soils of the Canadian River valley for seasonal crop rotations.

The region’s farmers faced significant challenges from unpredictable rainfall patterns and harsh prairie winds, which influenced their adoption of drought-resistant farming techniques specific to western Oklahoma.

Along the river valley, growers developed unique methods that combined traditional dry-farming practices with strategic irrigation from the Canadian River’s seasonal flow patterns.

Cotton and Corn Production

During Oklahoma’s early statehood period, cotton emerged as the region’s dominant commercial crop, with nearly one-fourth of cultivated land across most counties dedicated to its production by 1907.

You’d find cotton production centers stretching from Oklahoma City to the Arkansas River, with southern counties leading the way. While cotton flourished, corn established itself as a fierce competitor, particularly in Grady and Caddo counties.

- Over 300 cotton gins operated across Oklahoma at peak production

- McAlester, Ardmore, Mangum, and Oklahoma City housed key compressing plants

- Cotton reached 3.3 million acres by 1920, yielding 1.3 million bales

- Corn thrived in eastern Oklahoma’s higher rainfall regions

- Cotton prices soared to 34.98 cents per pound in 1919 before crashing to 9.4 cents in 1920

Seasonal Farming Challenges

While Oklahoma’s farmers faced numerous agricultural challenges, seasonal weather variability proved particularly intimidating throughout Ferguson’s history.

You’d need to carefully time your planting and harvesting to navigate the region’s unpredictable weather patterns, which could swing from severe drought to devastating floods.

Smart farmers practiced crop rotation to maintain soil health and implemented drought resilience strategies like planting native grasses.

When droughts hit – affecting up to 97.5% of Oklahoma at times – you’d watch your soil moisture vanish and crops struggle to germinate.

Your livelihood depended on adapting to these harsh realities.

Bermudagrass became a necessary addition to pastures, despite initial resistance, while supplemental feeding helped livestock survive when forage was scarce during off-seasons.

River Valley Growing Methods

The rich agricultural heritage of Ferguson’s River Valley stretches back over two millennia, with Native American farmers pioneering sustainable growing methods that would shape the region’s future.

You’ll find evidence of their sophisticated agricultural practices in the spiral culture that peaked around 1100 AD, establishing sustainable practices that European settlers would later adapt and modify.

The region’s farmers developed effective crop rotation systems that you can still see remnants of today:

- Deep plowing at 12-14 inches to preserve vital soil moisture

- Integration of alfalfa to naturally restore soil nutrients

- Alternating cash crops with forage crops for livestock feed

- Cultivation of drought-resistant pinto beans without irrigation

- Strategic mixing of corn, beans, and squash in traditional plots

These time-tested methods guaranteed Ferguson’s agricultural success through generations of farmers.

Cultural Significance

Pioneering African Americans established Ferguson, Oklahoma as one of many all-Black towns that emerged during the late 19th and early 20th centuries, creating essential safe havens for those seeking security and self-determination.

The town’s cultural resilience shone through its vibrant community life, with churches serving as spiritual and social anchors while local businesses fostered economic independence.

You’ll find Ferguson’s legacy deeply woven into Oklahoma’s unique distinction of housing more Black settlements than any other state.

The town’s historical narratives challenge traditional American stories, showcasing Black self-governance and economic agency during segregation.

Today, Ferguson stands as a powerful symbol of African American achievement, preserving stories of determination through its churches, businesses, and social venues that once formed the backbone of this thriving community.

The Decline Years

Despite early prosperity, Ferguson’s decline followed a familiar pattern seen across Oklahoma’s ghost towns, driven by the depletion of natural resources and shifting transportation routes.

You’ll find that economic factors hit hard when resource extraction became unprofitable, while transportation changes isolated the town from crucial trade routes.

Demographic shifts accelerated as younger residents sought opportunities elsewhere, and regulatory impacts further strained the local economy.

Key factors in Ferguson’s decline:

- Natural resource exhaustion led to an 80% population drop

- Rerouting of railroads and highways diverted essential commerce

- Young workers left for urban areas with better job prospects

- Loss of community services triggered a downward spiral

- Legal and policy changes added financial pressure on remaining businesses

Historical Impact

Once standing as a representation to Oklahoma’s early development, Ferguson left an indelible mark on the state’s historical landscape through its rapid rise and eventual submergence beneath Lake Marion.

The town’s historical significance extends beyond its physical remains, representing broader economic shifts that shaped Oklahoma’s development.

You’ll find Ferguson’s story mirrors countless other communities that flourished and faded as economic forces changed. Its advanced infrastructure, including paved streets and indoor plumbing, showcased the ambitions of early Oklahoma settlers.

The town’s evolution from a bustling hub with hotels, schools, and churches to a submerged ghost town exemplifies the volatile nature of frontier development.

While Lake Marion’s waters now cover Ferguson’s physical footprint, the community’s legacy persists as a reminder of Oklahoma’s dynamic past.

Modern-Day Remnants

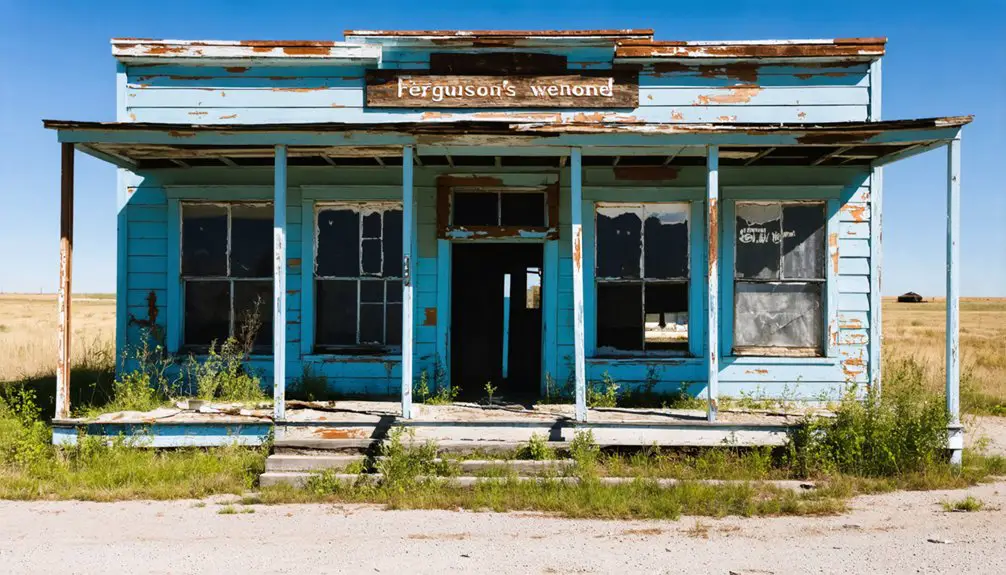

Today’s Ferguson stands as a stark reminder of its former importance, with scattered ruins and weathered remnants telling the story of what came before.

You’ll find extensive architectural decay throughout the site, where most structures have either vanished entirely or crumbled into foundations. Environmental neglect has transformed the landscape into a palette of browns and grays, with nature steadily reclaiming what humans left behind.

- Faded warning signs and “Keep Out” graffiti mark potentially hazardous buildings

- Former community landmarks, including the First Baptist Church demolished in 2011, exist only in memory

- Cracked roads and empty parking lots crisscross through overgrown vegetation

- Historic contamination from mining activities continues to impact the area

- Weathered historical markers offer glimpses into the town’s once-vibrant community life

Legacy and Remembrance

While many Oklahoma ghost towns have faded into obscurity, Ferguson’s legacy endures as a powerful symbol of African American resilience and self-determination in the early 20th century.

Originally named Salton before honoring Governor T.B. Ferguson in 1907, this Canadian River settlement represents a crucial chapter in Oklahoma’s network of all-black towns.

Through community remembrance efforts, you’ll find Ferguson’s story preserved in historical publications, exhibits, and local newspapers.

The town’s cultural preservation initiatives highlight its role in fostering African American leadership and maintaining traditions during the post-Reconstruction era.

As part of Oklahoma’s broader history, Ferguson stands as a monument to the freedmen and their descendants who built independent communities, creating spaces of opportunity despite the challenges they faced.

Frequently Asked Questions

Were There Any Notable Conflicts Between Ferguson Residents and Neighboring Communities?

You’ll find racial tensions marked Ferguson’s history, with documented community disputes between black residents and neighboring settlements, though specific details of conflicts aren’t extensively recorded in historical accounts.

What Natural Disasters or Severe Weather Events Impacted Ferguson’s History?

Like a hammer from heaven, the devastating 2008 EF4 tornado that struck your region brought massive destruction. You’d also face severe flooding from mine shaft overflow that contaminated local water supplies.

Did Ferguson Have Connections With Other All-Black Towns Through Marriage or Business?

You’ll find Ferguson maintained strong community ties with other all-Black towns through marriage networks and economic partnerships, as residents frequently traded goods, shared business ventures, and formed family connections across settlements.

What Traditional Ceremonies or Festivals Were Celebrated Annually in Ferguson?

You’d have found traditional celebrations like Juneteenth, harvest festivals, town anniversary events, and church revivals in Ferguson, but sadly, most annual festivities’ exact details remain lost to history.

Were There Any Famous Visitors or Politicians Who Came to Ferguson?

You won’t find records of any famous visitors or political events in Ferguson. The town’s small size and short-lived existence didn’t attract notable figures before it became a ghost town.

References

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_ghost_towns_in_Oklahoma

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zTKa5i1czdE

- https://www.okhistory.org/publications/ml/january2014.pdf

- http://www.african-nativeamerican.com/6-towns.htm

- https://kids.kiddle.co/List_of_ghost_towns_in_Oklahoma

- https://www.randomconnections.com/the-ghost-towns-of-lake-marion-part-2-ferguson/

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-jYN1_E2VV0

- https://okmag.com/blog/a-ghostly-site/

- https://www.okhistory.org/publications/enc/entry?entry=GH002

- http://dcminnerblues.com/black-towns/