Native American ghost towns represent more than abandoned structures—they’re testimonies of systematic displacement through policies like the Indian Removal Act and resource exploitation. You’ll find thousands of once-thriving communities emptied by forced relocations, railroad bypasses, and extractive industries that created brief booms before leaving devastating environmental impacts. Today, tribes transform these sites from symbols of loss into powerful vehicles for cultural reclamation and sovereignty. The full story reveals a complex narrative of resilience against historical erasure.

Key Takeaways

- Native American ghost towns resulted from forced displacements like the Indian Removal Act, which created abandoned villages during events like the Trail of Tears.

- Railroad expansion strategically bypassed Indigenous settlements, causing economic collapse in communities like Burnett when transportation routes changed.

- Resource extraction created boom-and-bust cycles that left abandoned towns and environmental damage, particularly evident in uranium mining areas across Navajo Nation.

- Indigenous communities maintain cultural connections to ancestral sites that outsiders may view as abandoned, emphasizing these places as living heritage.

- Systematic land dispossession through policies and land runs led to Indigenous communities losing nearly 99% of historically occupied territories.

Defining Native American Ghost Towns: Beyond Empty Buildings

While many associate ghost towns with tumbleweeds rolling through abandoned Western settlements, Native American ghost towns represent a far more complex historical and cultural reality.

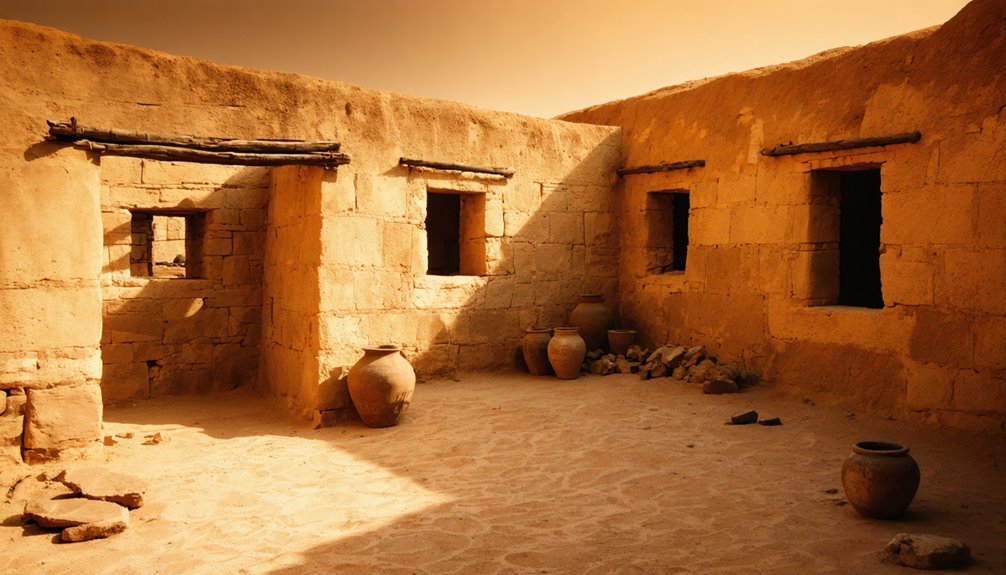

When you encounter these sites, you’re witnessing not just abandoned structures but cultural landscapes imbued with generations of meaning.

Unlike conventional ghost towns, these Indigenous sites often lack official recognition in historical records. Their boundaries extend beyond physical ruins to encompass the spiritual connections maintained by descendant communities.

You might notice subtle terrain alterations, ancient agricultural systems, or ceremonial spaces rather than obvious building remains.

The abandonment of these communities frequently stems from forced removal, assimilation policies, or economic pressures—not mere migration. Natural and human-made exclusion zones have also contributed to the creation of Native American ghost towns.

Understanding these places requires acknowledging both their tangible remains and the living cultural knowledge that continues to define their significance.

Unlike Arizona’s mining ghost towns that resulted from mineral depletion, Native American sites often reflect forced displacement rather than economic decline.

Forced Relocations and Land Runs: The Birth of Abandonment

When the United States government implemented the Indian Removal Act of 1830, it set in motion one of history’s most devastating forced migrations, creating America’s first ghost towns not through natural economic decline, but through deliberate policy.

You can trace the birth of these abandonments to the Trail of Tears, where approximately 4,000 Cherokee perished while being marched westward. The empty villages they left behind—once vibrant communities—became the first wave of Native ghost towns.

The Trail of Tears left more than human casualties—it created landscapes of absence where thriving Cherokee villages once stood.

Later, the land runs of 1889 transformed these spaces further, with 50,000 settlers claiming 2 million acres in a single day. These policies contributed to Indigenous people losing nearly 99% of their historically occupied lands across America.

Despite this systematic dispossession, tribal resilience narratives persist. Communities like the Citizen Potawatomi, relocated twice, have engaged in cultural reclamation efforts to reconnect with their original homelands, challenging the notion that these ghost towns represent only loss.

Railroad Dreams and Economic Realities in Tribal Territories

As railroads carved their iron paths across America’s heartland, they redefined both the physical and economic landscapes of tribal territories with a brutal efficiency that many Native communities couldn’t anticipate.

You’d witness Native settlements that once thrived suddenly wither when bypassed by steel tracks, while others experienced fleeting prosperity before inevitable decline. Towns like Burnett rose to prominence only to dissolve when railroad companies rerouted through Tecumseh, prioritizing profit over established communities. The creation of ghost towns like Sacred Heart Mission exemplified the fragile nature of development dependent on transportation networks. Tribes including the Pawnee, Sioux, and Arapaho faced severe displacement as railroads cut through their traditional hunting grounds.

Railroad expansion wasn’t random—companies strategically engineered spur lines to capture tribal resources and lands. The naming of stations after settlers rather than Indigenous families who lived there for generations exemplified the erasure accompanying economic displacement.

When automobiles eventually replaced trains as primary transportation, many isolated tribal communities, having already restructured around railroad dependencies, faced a second devastating economic blow.

Archaeological Remnants: What the Ruins Tell Us

The silent ruins scattered across ancestral Native territories speak volumes through their weathered walls and fallen beams if you know how to listen.

These archaeological discoveries reveal communities that thrived for centuries before being abandoned.

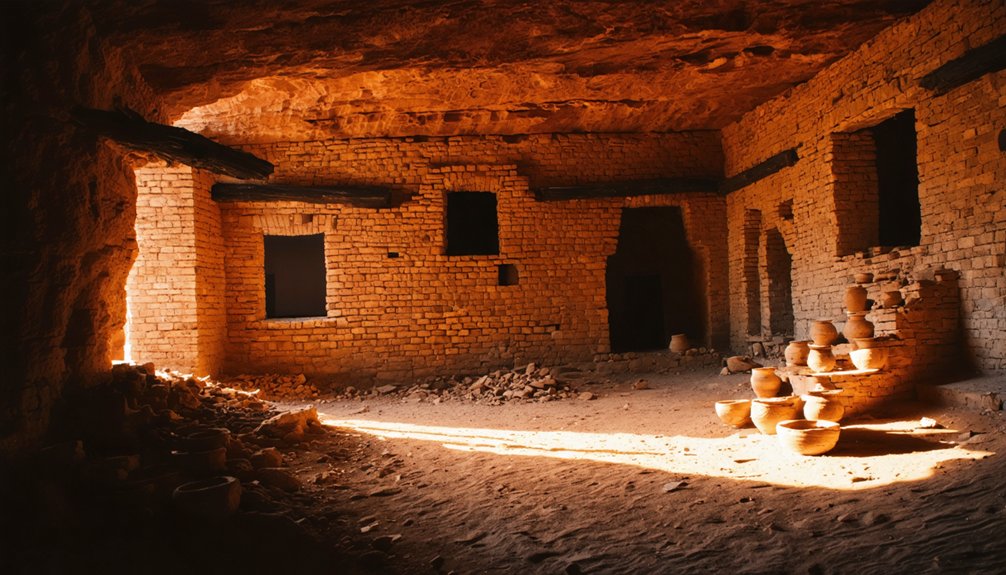

You’ll find evidence of sophisticated engineering in multi-room pueblos and cliff dwellings, accessed by ladders and built to withstand harsh environments.

The sunken kivas tell stories of ceremonial gatherings, while granaries speak to agricultural planning and food security.

Ancient lifestyles emerge through everyday objects—metates worn smooth from grinding corn, pottery shards decorated with cultural symbols, and petroglyphs etched into canyon walls.

The humble artifacts speak loudest—each worn metate and painted shard reveals generations of daily life etched into desert history.

Salt mines demonstrate resource management and trading networks that connected distant peoples.

When you encounter these spaces, you’re witnessing not just “ruins” but the resilient architecture of civilizations that adapted to changing conditions for millennia.

The circular pit houses of the Basketmaker people, dating back to 300 A.D., showcased early architectural innovation with their underground construction and roofs made of natural materials.

Many of these sites were abandoned due to extended drought conditions that made agricultural life unsustainable for the ancient inhabitants.

Cultural Memory and Heritage Preservation

Indigenous communities maintain deep cultural memories of their ancestral sites, connecting present generations to places where their ancestors once thrived. This cultural resilience manifests through ongoing relationships with places like Mesa Verde and Chaco Canyon—not as abandoned “ghost towns” but as living heritage.

When you visit these sites, you’re experiencing spaces where Native memory preservation continues through Traditional Cultural Properties protection and tribal-led interpretation. Organizations like NATHPO guarantee preservation approaches honor intangible heritage alongside physical structures. These spaces often contain sacred ceremonial kivas that remain spiritually significant to descendant peoples. Visitors must follow a strict ghost town code of ethics when exploring these culturally important sites.

Today’s tribal communities maintain authority through Tribal Historic Preservation Officers who guide respectful stewardship of their ancestors’ legacies. This decolonial approach recognizes that these places aren’t relics of the past—they’re integral parts of contemporary Native identity, requiring consultation with descendant communities for meaningful interpretation and protection.

Boom and Bust: Resource Extraction in Native Lands

When you examine the history of mining on Native lands, you’ll find a pattern of resource appropriation through dubious claims that systematically violated treaty rights, particularly evident in the Black Hills gold rush that illegally encroached on Sioux territory despite the Fort Laramie Treaty’s protections.

The discovery of valuable resources—from Michigan’s copper to Navajo uranium—consistently triggered exploitation cycles where tribal communities received minimal benefits while outsiders accumulated wealth through forced or severely underpaid Native labor. Native Americans had been mining pure copper veins in the Keweenaw Peninsula approximately 7,000 years before European settlers arrived and began claiming these resources as their own.

These extraction economies created temporary boom settlements that collapsed once resources depleted, leaving behind environmental devastation and cultural disruption that continues to affect tribal nations today.

Mining Claims and Conflict

Throughout America’s mining boom periods, ancestral Native lands became battlegrounds of competing interests, pitting tribal sovereignty against government-sanctioned resource extraction.

You’ll find the evidence in stark numbers: over 600,000 Native people live within six miles of hardrock mines in the Western states, with more than 160,000 abandoned mines scarring their territories.

The BLM’s oversight of mining regulations reveals a troubling pattern—approving 500 hardrock operations between 2000-2018 while tribes struggle to protect sacred lands.

When Native nations invoke their rights through legal channels, they’re often outspent by industry lobbyists who poured $18.5 million into influencing policy in 2021 alone.

The federal government’s history of breaking treaties once minerals were discovered continues today through fast-tracked approvals that circumvent meaningful tribal consultation, undermining tribal sovereignty at every turn.

Precious Metals, Scarce Rights

As glittering veins of gold and silver drew waves of prospectors to Native territories from the Southwest to the Great Basin, tribal nations found their rights vanishing as quickly as the precious metals were extracted.

You’d barely recognize the Santa Cruz Valley or the San Juan Mountains during these frenzied booms—lands transformed overnight without tribal consent. While mining companies claimed exclusive rights to these scarce resources, Native communities received no such protections.

The pattern repeated with uranium in Navajo Nation during the 1940s, creating temporary wealth that vanished when the mines closed.

These boom-and-bust cycles left behind more than abandoned shafts and ghost towns—they created generations of economic instability, contaminated water sources, and chronic health problems.

The mining rights that corporations so enthusiastically secured never extended to the right of Native peoples to protect their lands and futures.

Forced Labor Systems

The extraction of resources from Native lands didn’t just take the form of mining—it extended to the exploitation of Indigenous bodies themselves through complex systems of forced labor.

You’d find these systems varied across regions: California missions shackled Natives under religious pretexts, subjecting them to flogging and confinement while extracting crucial economic labor.

During the Gold Rush, miners exploited Indigenous workers after decimating their populations by nearly two-thirds within two years.

In the Southeast, even Native nations incorporated African American slavery into their societies, with over 8,000 enslaved people in Indian Territory by 1861.

The historical implications of these interconnected labor exploitation systems persist today, as Indigenous communities were transported across continents, forced to work in mines, plantations, and domestic roles—their bodies commodified alongside the resources taken from their lands.

Notable Ghost Towns of the Citizen Potawatomi Nation

You’ll find the legacy of Pleasant Prairie and Uniontown particularly poignant as these once-vibrant Potawatomi settlements succumbed to shifting railroad priorities and economic pressures after forced relocations.

Railroad development promised economic integration but ultimately contributed to the dissolution of these communities, as lines bypassed settlements or failed to deliver promised prosperity.

These ghost towns now stand as powerful reminders of the Potawatomi Nation’s resilience through multiple displacements, revealing how transportation infrastructure both connected and dismantled Indigenous population centers.

Railroads Reshaping Communities

Railroad development during the late 19th and early 20th centuries fundamentally transformed Citizen Potawatomi Nation settlements, creating a pattern of community rise and decline that’s still visible today.

You’ll find that towns previously established around allotments and cart roads quickly shifted their focus to railroad corridors, where economic significance concentrated.

The railroad impact was decisive—communities like Burnett and Uniontown dissolved when residents relocated to rail-connected towns for better access to markets and services.

The Rock Island Railroad‘s placement determined which settlements thrived and which faded into history.

Railroad companies acquired vast tracts of Potawatomi land, often through tax defaults or following the 1867 Treaty, which facilitated land sales funding the tribe’s forced relocation to Indian Territory.

This community transformation represents not just physical displacement but a deeper story of resilience amid colonial-imposed change.

Lost Tribal Centers

While railroad expansion determined the fate of many settlements, Citizen Potawatomi communities had already experienced profound displacement through federal policies long before the iron horse arrived. You can trace this pattern through ghost towns like Pleasant Prairie, the first Oklahoma homeland after the devastating Trail of Death claimed 42 lives during forced relocation.

Uniontown emerged as a government attempt to consolidate autonomous Potawatomi bands, only to be twice destroyed by cholera outbreaks. Nearby Plowboy served as a cultural stronghold where families maintained traditional lifeways despite federal disruption.

These abandoned centers reflect both economic shifts and indigenous resilience. Though Pleasant Prairie officially dissolved in 1907 as residents moved toward Shawnee’s opportunities, its cultural significance remains as the foundation from which many Potawatomi families rebuilt after generations of forced movement.

Ancient Pueblos to Modern Ruins: A Thousand Years of History

A thousand years of Native American architectural history stretches from the magnificent ancient Puebloan settlements to the ghostly remains of more recent communities.

You can trace this timeline from Chaco Canyon’s great houses, constructed around 850 CE, through their peak in 1050, to their mysterious abandonment by 1150.

This ancient architecture didn’t simply disappear—it evolved. As Puebloan peoples migrated to establish new communities like Acoma and Zuni in the 1300s, they carried forward building traditions while adapting to changing circumstances.

Meanwhile, the massive urban center of Cahokia supported up to 50,000 people during its zenith.

Cultural resilience persisted even as European contact brought devastating diseases and conflict.

Tourism and Interpretation: Balancing Access With Respect

Native American ghost towns now face a delicate balancing act as tourism grows in tribal communities across America.

You’ll find infrastructure often inadequate—places like Pine Ridge have minimal lodging options while visitor numbers continue to rise toward projected 2.4 million international tourists by 2020.

Community-led initiatives prioritize cultural sensitivity, allowing tribes to tell their own stories rather than having outsiders interpret their heritage.

This approach helps prevent commodification while generating essential income for development projects in economically challenged areas.

When you visit these sites, you’re participating in a complex exchange.

Sustainable tourism requires your respect for authenticity and local approval.

The challenge remains: how to preserve cultural identity while sharing it with outsiders.

The most successful models involve tribal communities in every aspect of tourism planning, ensuring both economic benefits and cultural preservation.

Frequently Asked Questions

What Indigenous Languages Survive in Ghost Town Place Names Today?

You’ll find Algonquian, Siouan, Iroquoian, and Uto-Aztecan languages preserved in ghost town names today, contributing to language preservation through place name etymology that honors their original cultural significance.

How Did Native Women’s Roles Change After Town Abandonment?

Like resilient reeds bending with the wind, you’d see women’s roles shift toward cultural resilience through spiritual leadership, economic shifts in portable crafts, and strengthened family networks while maintaining decision-making influence despite colonial disruption.

Were Any Ghost Towns Reclaimed by Tribes in Recent Decades?

Yes, you’ve witnessed tribal reclamation of several abandoned sites in recent decades, including Kiowa’s recovery of Indian City USA and the Rappahannock’s acquisition of Fones Cliffs, sparking cultural resurgence across Native nations.

How Did Disease Impact the Abandonment of Native Settlements?

Coincidentally, you’re witnessing history repeat itself. Disease transmission devastated Native communities, forcing abandonment of traditional settlement patterns as mortality rates reached 90%, creating ghost villages where vibrant communities once thrived.

What Traditional Ceremonies Continued Despite Town Abandonment?

Despite displacement, you’ll find Native peoples maintained ceremonial practices like sweat lodges, Ghost Dances, harvest rituals, and private ceremonies, preserving their spiritual significance while adapting traditions under oppressive conditions.

References

- https://www.potawatomi.org/blog/2021/04/09/remembering-potawatomi-ghost-towns/

- https://www.visitutah.com/things-to-do/history-culture/ghost-towns

- https://www.newmexico.org/places-to-visit/ghost-towns/

- https://www.thecollector.com/the-5-oldest-native-american-towns-in-the-united-states/

- https://www.christywanders.com/2024/08/top-ghost-towns-for-history-buffs.html

- https://www.scmp.com/lifestyle/travel-leisure/article/3254037/ultimate-us-ghost-towns-exploring-ancient-native-americans-settlements-and-culture-and-camping-under

- https://www.legendsofamerica.com/gt-hiddentales/

- https://www.gilahot.com/ghost_towns.shtml

- https://www.nps.gov/slbe/learn/historyculture/ghosttowns.htm

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ghost_town