Mining towns across America experienced dramatic boom-and-bust cycles following gold and mineral discoveries in the 19th century. You’ll find these communities rapidly developed infrastructure, social hierarchies, and cultural centers, often under corporate control. When resources depleted, towns faced economic collapse, leaving environmental contamination and abandoned structures. Today, these ghost towns serve as historical time capsules, with many finding new purpose through tourism and preservation efforts. Their weathered buildings tell stories of America’s industrial heritage.

Key Takeaways

- Mining towns rapidly formed after gold discoveries, developing from camps to communities with diverse immigrant populations.

- Social hierarchies defined these communities, with wealthy mine owners on higher ground and laborers in company housing below.

- Corporate control extended beyond mining operations to rail lines, housing, schools, and entertainment venues.

- Economic decline occurred through deindustrialization, reduced employment, population migration, and fiscal collapse.

- Many abandoned mining towns now face preservation challenges while others have successfully transformed into tourist destinations.

The Gold Fever: How Mining Strikes Created Instant Communities

When prospectors discovered gold at California’s Sutter’s Mill in 1848, they unwittingly ignited a national phenomenon that would transform America’s frontier. Telegraph and newspapers spread news of strikes rapidly, launching tens of thousands of “forty-niners” westward.

These gold rushes catalyzed the overnight formation of mining camps that evolved into bustling towns like Cripple Creek and Lead City.

You’d find these instant communities characterized by remarkable cultural exchange, as immigrants from around the world—including 20,000 Chinese by 1852—converged on promising diggings.

Community dynamics emerged rapidly through necessity: informal leadership structures, makeshift law enforcement, and essential institutions like churches and saloons materialized within months.

These multicultural boomtowns became America’s first international cities, where diverse languages, customs, and traditions coexisted in the shared pursuit of mineral wealth. Similar to California’s gold rush, General George Armstrong Custer’s discovery in the Black Hills triggered another significant mining boom in 1874. In Cripple Creek, the Western Federation of Miners organized workers to fight for an eight-hour workday against mine owners who attempted to increase hours without additional compensation.

Boomtown Infrastructure: Building Cities in the Wilderness

Unlike the spontaneous social structures that emerged in mining communities, the physical infrastructure of boomtowns required deliberate planning and substantial investment to transform wilderness outposts into functioning settlements.

You’d find engineers and surveyors mapping mineral deposits while simultaneously designing town layouts that balanced proximity to ore with access to water and transportation routes.

Resource allocation presented constant challenges as settlements expanded rapidly. Mining corporations often vertically integrated operations, controlling everything from rail lines to housing. Large conglomerate corporations emerged to manage these complex operations, centralizing control over multiple aspects of mining infrastructure and transportation networks.

The corporate grip on boomtowns extended from mineshafts to doorsteps, leaving little beyond their calculated control.

Infrastructure planning encompassed both immediate needs—hastily constructed dwellings, general stores, and saloons—and anticipation of future growth through transportation networks that connected remote locations to supply centers.

The contrast between economic and social infrastructure was stark; while commercial establishments appeared quickly, public services like schools, medical facilities, and sanitation systems struggled to keep pace with significant population increase over a 5 to 12 year construction period.

Daily Life in Mining Towns: From Saloons to Schools

You’d find distinct social hierarchies in mining towns, with mine owners and managers occupying lavish homes on hills while laborers crowded into company housing below.

Churches became vital community centers where the thirteen different nationalities represented in Ernest by 1909 could gather and preserve their ethnic traditions through worship and celebration.

Schoolhouses emerged as communities stabilized, often doubling as community centers where residents could gather for educational and social purposes alike.

Theaters and opera houses signaled a town’s prosperity, offering entertainment that transcended class divisions while simultaneously reinforcing them through seating arrangements and ticket pricing.

Women managed households with exceptional fortitude, maintaining homes and families while enduring far greater difficulties than those faced by the miners themselves.

Social Hierarchy Formation

Mining towns across America developed intricate social hierarchies that determined nearly every aspect of residents’ lives. You’d immediately recognize your social position by where your house stood—proprietors enjoyed ornate residences on higher ground while you’d find laborers in identical cottages or boarding houses below.

Social stratification manifested through rigid occupational roles that dictated your status, earnings, and living conditions. If you were an immigrant, you’d likely face ethnic segregation, with housing arranged to keep your group together, reinforcing job hierarchies. Companies typically maintained a careful ethnic balance among workers to prevent unified labor movements and minimize conflict. This approach mirrored the paternalistic control seen in model company towns like Pullman, where owners dictated not just work but lifestyle choices.

Company officials controlled who received housing, typically favoring married men over bachelors and skilled workers over unskilled ones.

Despite these divisions, you might find some solidarity through shared labor experiences, forming what miners called a “clan”—a communal identity that occasionally transcended the carefully constructed social boundaries imposed by mining companies.

Schoolhouses and Theaters

Beyond the rigid social structures that defined living arrangements, the cultural heart of mining towns beat within their schoolhouses and theaters.

You’d find coal companies constructing these essential buildings not merely as services but as instruments of community cohesion and corporate control. School architecture typically reflected utilitarian designs, with buildings often doubling as community gathering spaces. Teachers received company paychecks, teaching in facilities that sometimes enforced racial segregation. The majority of students were children of immigrant workers, reflecting the demographic makeup of most company towns during this era. Theaters in northern mining communities served as vital escapes for lumberjacks and miners, reflecting the cultural landscape of the early twentieth century.

Theatrical performances became weekend rituals in purpose-built venues like Sagamore’s multi-functional theater, which housed restaurants and meeting spaces alongside entertainment areas. These weren’t just places for amusement—they represented the company’s paternalistic approach to worker management while simultaneously providing miners’ families rare opportunities for cultural enrichment and social interaction.

Together, schools and theaters mitigated the isolation of remote industrial outposts while reinforcing the company’s omnipresence in daily life.

The Perfect Storm: Why Mining Towns Collapsed

While numerous factors contributed to the decline of American mining communities, a perfect economic storm developed through the convergence of deindustrialization, labor exploitation, demographic shifts, and fiscal collapse.

You’re witnessing the results of massive economic decline across former industrial strongholds where community resilience was severely tested.

Consider these devastating trends:

- Manufacturing capacity shifted overseas while coal production plummeted—by 80% in Central Appalachia within just one decade

- Mining employment dropped 50% between 2011-2016, with remaining jobs paying far less than historical rates

- Working-age population fled these regions, creating a damaging brain drain

- Local tax revenues were cut in half while public service demands increased

This catastrophic combination left mining towns without the economic foundation, workforce, or fiscal capacity to reinvent themselves.

Environmental Legacy: The Toxic Aftermath of Abandoned Mines

The economic collapse of mining towns represents only half of their tragic narrative, as these abandoned communities continue to confront a devastating environmental inheritance decades after the last mines closed.

You’ll find this toxic legacy manifests primarily through acid mine drainage, where exposed metal sulfides create sulfuric acid that leaches heavy metals into waterways. The EPA estimates these contaminants have poisoned 40% of American rivers and 50% of lakes.

At Oklahoma’s Tar Creek, children suffer documented brain damage from elevated blood lead levels. Beyond water pollution, abandoned mines create physical hazards including tunnel collapses, sinkhole formation, and deadly gas accumulations.

Environmental remediation efforts remain vastly underfunded, with federal agencies spending $2.9 billion between 2008-2017 while BLM estimates require $4.7 billion for adequate cleanup.

Ghost Towns as Time Capsules: Preserved Mining History

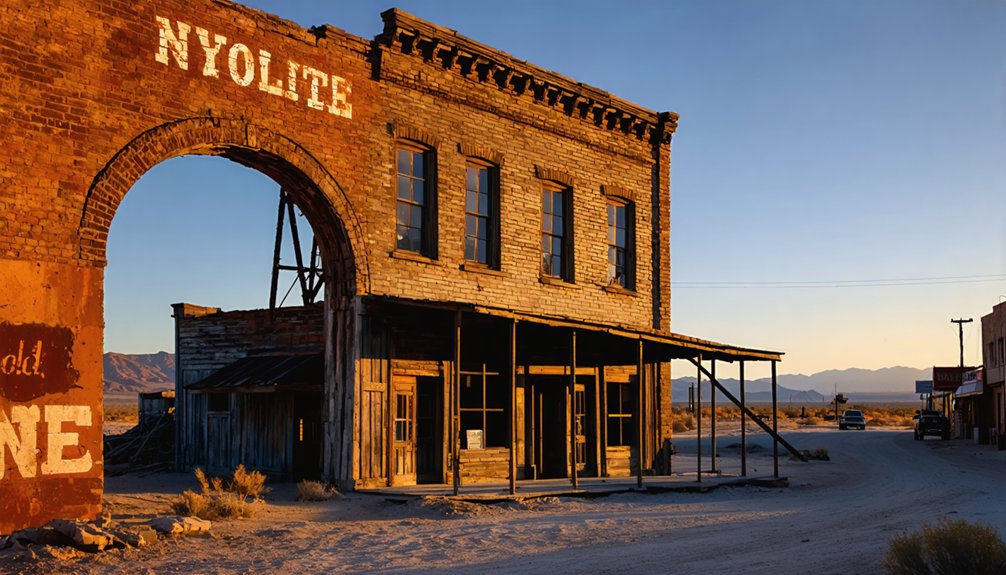

When you tour America’s ghost towns, you’ll encounter unique architectural preservation challenges as fragile wooden structures battle the elements while preserving authentic snapshots of mining-era life.

Preservation teams must balance maintaining “arrested decay” with ensuring visitor safety, often employing specialized techniques to stabilize buildings without compromising their historical integrity.

The carefully curated artifacts within these preserved spaces—from rusted mining equipment to personal possessions left behind during hasty departures—tell compelling stories about the technological innovations, harsh working conditions, and daily struggles that defined America’s mining boom periods.

Architectural Preservation Challenges

Preserving America’s abandoned mining towns presents extraordinary challenges that extend beyond mere architectural conservation to encompass geographic isolation, environmental hazards, and resource limitations.

Preservation techniques must contend with structures perched on cliff edges requiring helicopter access for materials, while structural stabilization efforts battle both gravity and wildlife damage from creatures like marmots.

Funding challenges create significant hurdles for preservationists:

- Multi-million dollar commitments exist for prominent sites, but many smaller towns struggle to secure adequate investment

- Volunteer support and in-kind contributions often fill critical resource gaps

- Regulatory hurdles require navigation of both historic preservation laws and environmental remediation requirements

- Community involvement becomes essential to overcome the economic limitations that threaten these irreplaceable historical assets

Environmental remediation must be integrated with conservation work, balancing cultural preservation with contamination concerns.

Artifacts Tell Mining Stories

Across America’s forgotten mining landscapes, abandoned towns serve as extraordinary historical time capsules, preserving tangible evidence of frontier industrialization that you won’t find in conventional museums.

These sites reveal mining heritage through artifacts of remarkable authenticity—century-old tools remain exactly where workers last placed them, and intact ventilation systems demonstrate engineering ingenuity.

The artifact significance extends beyond equipment; you’ll find dining tables still set and stores still stocked in places like Bodie, California, frozen since the 1870s.

Climate-controlled archives in Silverton protect thousands of documents while wooden structures in St. Elmo showcase daily life infrastructure.

Even hidden treasures occasionally emerge, like the 5-ounce gold dust bag discovered during preservation work at Shenandoah-Dives Mill—tangible connections to America’s industrial past that continue informing our understanding of western expansion.

Tourism Revival: How Forgotten Towns Found New Purpose

Many forgotten mining towns throughout the United States have experienced remarkable revivals as tourist destinations after their original economic purpose vanished with the depletion of mineral resources.

These transformations demonstrate innovative approaches to heritage preservation while capitalizing on tourism trends that favor authentic historical experiences.

When you visit these revitalized settlements, you’ll find:

- Carefully preserved structures like Bodie’s iconic Erie Street functioning as outdoor museums

- Artistic communities flourishing in former industrial centers, as exemplified by Jerome, Arizona

- Diversified attractions combining historical education with entertainment, from guided mine tours to ziplines

- Strategic infrastructure improvements making remote locations accessible to day-trippers

Towns like Virginia City, Calico, and Leadville have successfully balanced historical authenticity with economic sustainability, creating destinations that honor their industrial heritage while providing contemporary visitor experiences that support ongoing preservation efforts.

Frequently Asked Questions

How Did Women Influence Social Development in Isolated Mining Communities?

You’d think men built these towns, but surprise! Women’s roles were essential—organizing social events, managing households, and fostering community cohesion through mutual support networks that ultimately guaranteed mining settlements’ survival and cultural development.

What Indigenous Communities Were Displaced by Mining Town Establishment?

You’ll find Cherokee, Choctaw, Creek, Chickasaw, Hualapai, Numu/Nuwu, Newe, and California Indigenous peoples were victims of displacement and cultural erasure when mining operations established towns on their ancestral territories.

How Did Mining Towns Handle Law Enforcement Before Formal Governments?

You’d witness self-governing, self-protecting mining communities where vigilante justice prevailed alongside elected community policing structures. Miners created people’s courts, established codes of conduct, and administered punishments through collective decision-making without formal governmental oversight.

What Happened to Mining Equipment After Towns Were Abandoned?

You’ll find mining equipment often abandoned in place when removal costs exceeded salvage value. This economic impact created rusting time capsules, leaving behind valuable machinery that wasn’t economically feasible to transport.

Did Any Mining Towns Successfully Transition to Alternative Industries?

Yes, some mining towns thrived after coal. You’ll find Pittsburgh’s remarkable 40-year transformation exemplifies economic diversification, evolving from steel manufacturing into technology and healthcare sectors through university partnerships and sustainable practices in former industrial complexes.

References

- https://www.geotab.com/ghost-towns/

- https://www.mentalfloss.com/geography/wanderlust/creepiest-ghost-towns-united-states

- https://albiongould.com/ghost-towns-to-visit-in-the-states/

- https://westernmininghistory.com/map/

- https://www.blackhillsbadlands.com/blog/post/old-west-legends-mines-ghost-towns-route-reimagined/

- https://www.smithsonianmag.com/sponsored/nevadas-living-and-abandoned-ghost-towns-180983342/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ghost_town

- https://savingplaces.org/stories/explore-wild-west-mining-history-in-nevada-ghost-towns

- https://www.loveexploring.com/gallerylist/188219/the-us-state-with-the-most-ghost-towns-revealed

- https://coloradogeologicalsurvey.org/minerals/historic-mining-districts/