Fort Mohave isn’t your typical ghost town. Established in 1859 during the Mohave War, this military outpost protected travelers along the Colorado River where soldiers endured brutal 110°F heat. After Civil War abandonment and reoccupation, it later transformed into a Native American boarding school until 1930. Today, you’ll find weathered stone walls and foundations on Fort Mojave Indian Tribe land, requiring tribal permission to visit. The fort’s remains whisper stories of frontier conflict and cultural resilience.

Key Takeaways

- Fort Mohave was established in 1859 as a military outpost but now exists only as archaeological remains with weathered stone walls and foundations.

- After its military abandonment, the fort transitioned to a Native American boarding school until 1930, after which it became essentially a ghost town.

- Visitors must obtain permits from the Fort Mojave Indian Tribe as the site lies within tribal jurisdiction.

- The extreme desert conditions with temperatures reaching 111°F contributed to the fort’s eventual abandonment and deterioration.

- The site represents Arizona’s frontier history and the complex relationship between American westward expansion and indigenous sovereignty.

Origins of Fort Mohave: The Mohave War and Military Necessity

As the dust from the California Gold Rush settled in the late 1850s, tensions ignited along the Colorado River where the ancestral Pipa Aha Macav—”People by the River”—found their lands increasingly crossed by American settlers and miners seeking fortune.

This encroachment sparked the Mohave War (1858-1859), a conflict where native resistance met calculated military strategy.

You’d have witnessed Major L.A. Armistead establishing Camp Colorado—later Fort Mohave—on April 19, 1859, under orders from Brigadier General Edwin V. Sumner. The fort’s strategic position overlooking the Colorado River crossing served both as protection for westward travelers and as a power projection point to subdue Mohave warriors. The fort was built on a commanding bluff that provided a crucial vantage point for military operations.

Through guerrilla warfare and raids, the Mohave fought to protect their homeland until superior weapons and tactics forced their surrender, culminating in the 1859 peace treaty. Lieutenant Colonel William Hoffman’s Second Mohave Expedition had deployed over 600 soldiers to establish the fort and negotiate the eventual peace with Mohave chiefs.

Life at a Desert Outpost: Surviving 110°F Heat and Isolation

When soldiers first arrived at Fort Mohave in 1859, they encountered an environment that seemed determined to break their resolve.

Facing summer highs of 111°F and mere 6 inches of annual rainfall, desert survival required immediate adaptation.

You would have found yourself developing heat adaptation strategies essential to endure this harsh posting:

- Restructuring your day to avoid peak heat, working before dawn and after sunset

- Learning water conservation techniques, carefully rationing the precious resource drawn from the Colorado River

- Building thick-walled shelters with small windows to minimize heat gain and catch rare breeze currents

The extreme isolation compounded these challenges.

Isolated from civilization, soldiers faced not just nature’s wrath, but the crushing weight of desolation itself.

With 290 sunny days annually and seven months above 100°F, your resilience would be tested constantly in this remote desert outpost where self-sufficiency meant survival. The station’s comfort index rating of 3.9 during summer months reflected the brutally oppressive conditions soldiers endured.

The fort was situated in what would become an important ecological transition zone where the creosote bush series dominated the surrounding landscape, offering little respite from the relentless sun.

Strategic Importance: Controlling the Colorado River Corridor

The harsh desert conditions that tested soldiers’ endurance at Fort Mohave were endured for a singular purpose: command of the Colorado River.

When you stand at this historic site, you’re overlooking what was once a significant lifeline for the expanding western frontier. Established in 1859, the fort’s strategic position allowed military forces to monitor river navigation and secure this essential transportation corridor.

Before railroads stretched across the Southwest, the Colorado served as the primary route for military supply, trade, and communication. Controlling this river crossing point meant controlling movement between California, Arizona, and Nevada territories.

Though steamboats couldn’t navigate much farther upstream due to treacherous rapids and sandbars, Fort Mohave’s position at the highest reliable navigation point made it an invaluable checkpoint for regional security and commerce. The fort’s location at this critical juncture exemplifies the ongoing struggle for water rights allocation that would later be formalized in the 1922 Colorado River Compact. The landmark compact would eventually divide the river’s waters between the Upper and Lower Basin states, allocating 7.5 million acre-feet to each basin annually.

The Pipa Aha Macav: Native Relations and Cultural Impact

Long before Fort Mohave cast its military shadow across the Colorado River valley, these lands belonged to the Pipa Aha Macav—”People by the River”—whose ancient connection to these waters stretches back countless generations.

The tribe’s cultural resilience persisted despite three devastating waves of colonization:

- Military subjugation beginning in 1859, restricting freedom of movement and disrupting traditional riverine agriculture.

- Administrative control transfer to the Bureau of Indian Affairs in 1890, imposing federal oversight of tribal affairs.

- Forced attendance at military-style boarding schools where children were punished for speaking their language.

When you visit what remains of Fort Mohave today, you’re standing on contested ground where the Pipa Aha Macav history continues despite systematic attempts at cultural erasure—their identity preserved through determined resistance to assimilation policies. The Spanish explorer Melchor Díaz was the first European visitor to encounter this established agricultural society during his expedition in 1540. American miners and settlers later contributed to cultural misconceptions by misnaming them Mohave Indians, a distortion of their true tribal identity.

Civil War Abandonment and 1863 Reoccupation

You’ll find nothing but charred remains at Fort Mohave when you visit in 1861, as General Sumner ordered the burning of structures when he sent regular troops eastward for Civil War service.

While Confederate forces never materialized to claim this strategic Colorado River crossing during its two-year abandonment, the fort stood empty until California Volunteers reestablished the military presence in May 1863.

Your journey along the Mohave-Prescott Road would have been considerably safer after this reoccupation, as Companies B and I of the 4th California Infantry secured this essential transportation corridor and cultivated peaceful relations with local Mojave Indians. The fort was originally established at Beales Crossing in the Mohave Valley, making it a vital point for controlling river passage. This location became significant following the Battle of the Colorado River in August 1859, which resulted in numerous Mojave casualties and marked a turning point in American control of the region.

Hasty Union Retreat

As Union forces scrambled to address the mounting crisis back East in 1861, Fort Mohave faced swift abandonment under General Sumner’s orders, creating a significant power vacuum along the Colorado River corridor.

The Strategic Withdrawal left you without military protection for nearly two years as the Civil War consumed national resources.

The hasty Union Retreat dramatically transformed the region in three ways:

- Local Mojave tribes regained temporary autonomy, with some leaders pursuing peace while others resisted American influence.

- Travelers lost essential protection at this critical Colorado River crossing point.

- Trade routes became increasingly dangerous without military oversight.

You’d have witnessed complete desertion of the fort, standing empty and vulnerable until 1863 when California Infantry companies finally returned to restore order and protection along the Mohave-Prescott road.

Confederate Threat Averted

The danger from Confederate forces in the Southwest during 1861 sparked Fort Mohave’s initial abandonment, revealing Civil War tensions that reached even this remote outpost.

Under General Sumner’s orders, soldiers torched their own buildings in a calculated military strategy to prevent Confederate sympathizers from claiming this strategic Colorado River crossing.

For two years, the area remained in limbo while the Mohave tribe navigated changing power dynamics.

Chief Yara tav pursued tribal diplomacy, leading many toward peace, while Homoseh awahot’s faction resisted reservation life.

Rebuilding Strategic Position

Following the tense two-year vacancy after its abandonment in 1861, Fort Mohave rose from its charred remains when Companies B and I of the 4th California Infantry reclaimed the strategic outpost on May 19, 1863.

You’d have witnessed soldiers rebuilding what would become Camp Mojave, establishing control over Beale’s Crossing and critical western migration routes.

The fort’s revival served three key purposes:

- Securing military logistics along the Colorado River corridor

- Protecting miners, settlers, and steamboat traffic from potential threats

- Countering lingering Confederate sympathies in the territory

As you traveled through the area, you’d notice soldiers weren’t just performing military duties—they were actively engaged in economic integration, staking mining claims and fostering peaceful relations with Mojave Indians, creating stability that benefited both military strategy and civilian prosperity.

From Battlefield to Classroom: Transition to Indian School

When Fort Mojave‘s military personnel marched away for the final time in 1890, they left behind more than just abandoned barracks and empty parade grounds.

The War Department quickly transferred the site to the Bureau of Indian Affairs, transforming a former military installation into an instrument of cultural assimilation.

Under Superintendent Samuel M. McCowan’s direction, the newly established Fort Mojave Indian School welcomed Native American children as young as eight years old.

You’d have witnessed these youngsters learning English, mathematics, and practical trades—boys in carpentry and farming, girls in domestic skills—all part of federal educational policies designed to “Americanize” them.

The school’s population swelled to over 300 students at its peak, with children separated from their families and tribal traditions until the facility’s closure in 1930.

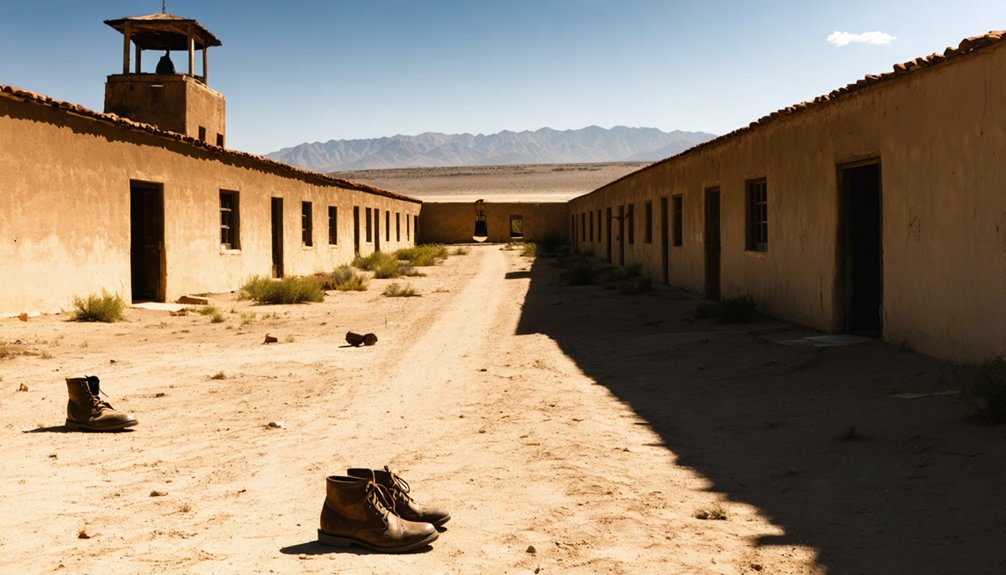

Archaeological Remains: What Survives Today

As you walk the bluffs overlooking the Colorado River today, you’ll encounter weathered stone walls and partially buried brick foundations that mark where Fort Mohave once stood.

The site’s archaeological remains include traces of water towers and storage facilities, with scattered artifacts revealing the daily lives of soldiers and later boarding school residents.

These physical remnants, alongside nearby geoglyphs and indigenous artifacts, tell the complex story of a place transformed from military outpost to educational institution while sitting atop land rich with thousands of years of Native American history.

Stone Walls Still Standing

Sentinels of a bygone era, the stone walls of Fort Mohave stand as the most enduring remnants of this historic military outpost.

You’ll find these walls, constructed with local stone and mud mortar, have outlasted their adobe counterparts with remarkable stone wall durability. The officers’ quarters and commissary fragments provide the clearest glimpse into historical construction methods used during the fort’s operation.

When you visit the site today, three notable features include:

- Stone wall sections from the officers’ quarters

- Partial remains of the post commissary

- Evidence of salvage and repurposing during the Indian school period

Despite salvage efforts following the military’s 1890 departure, these steadfast structures continue to tell Fort Mohave’s story through their weathered but resilient presence.

Uncovered Foundation Footprints

Beneath the desert soil at Fort Mohave, archaeological investigations have uncovered the ghostly outlines of what once stood as a bustling military outpost.

You’ll find weathered stone foundations just barely visible above ground level—the last physical remnants of officers’ quarters and commissary buildings.

Unlike the adobe walls that have long since returned to earth, these stone foundation footprints have proven remarkably durable.

Foundation documentation efforts reveal how the military post was organized, though later Indian school construction has complicated this work by overlapping original structures.

The archaeological significance of these humble remains can’t be overstated—they’re your primary window into understanding daily frontier military life.

When you visit, you’re walking among the carefully mapped traces of Arizona’s territorial past, each stone outline telling stories that would otherwise be lost to time.

Artifacts Reveal Daily Life

While explorers today search the sun-bleached terrain of Fort Mohave, they’re greeted by a remarkable array of physical evidence that tells the story of frontier life.

The artifact significance extends beyond mere objects—they’re tangible connections to those who sought fortune in this harsh landscape.

Evidence of daily life appears in three distinct categories:

- Industrial remnants – Steam-powered arrastras, mining shafts reaching 435 feet deep, and head frames that once facilitated the extraction of silver and gold.

- Infrastructure elements – Brick foundations, water towers, and oil storage facilities that supported a community of over 100 settlers.

- Commercial traces – Steel safes from mining offices, scattered remnants of saloons, hotels, and professional buildings where doctors and lawyers once served the community.

The Fort’s Architecture: Adobe, Stone, and Desert Building Techniques

The harsh desert sun beating down on Fort Mohave shaped not only the daily routines of its inhabitants but also the very architecture that sheltered them.

As you walk the remnants today, you’ll notice foundations of buildings constructed primarily from adobe and local stone—materials that provided essential desert insulation against temperatures often exceeding 110°F.

The military architecture featured thick-walled structures designed with thermal mass principles: absorbing heat by day and releasing it at night.

Stone buildings, including officers’ quarters, were constructed with local rock and mud mortar, outlasting their adobe counterparts.

The fort’s layout centered around a parade ground, with building placement maximizing shade and natural ventilation.

These construction techniques reflected both frontier practicality and indigenous knowledge, adapted specifically to survive the unforgiving Mohave Desert.

Visiting the Ghost Town: Tribal Permissions and Access

Visitors planning to explore Fort Mohave‘s haunting remains must first navigate a complex landscape of tribal permissions and sovereignty restrictions. The ghost town lies within Fort Mojave Indian Tribe jurisdiction, requiring your respect for tribal sovereignty and adherence to specific regulations.

Before commencing your journey into this desert time capsule, remember:

- Contact tribal offices to secure necessary permits – unauthorized entry constitutes trespassing under tribal law.

- Prepare for harsh desert conditions with sturdy footwear, sun protection, and ample water.

- Follow all posted signage and practice visitor compliance regarding photography, artifacts, and sacred areas.

Group visits and commercial activities require additional approvals.

The nearby Spirit Mountain holds profound spiritual significance to the Mojave people, demanding reverence during your exploration of this historically rich landscape.

Fort Mohave’s Legacy in Arizona Frontier History

Established as a military outpost in 1859, Fort Mohave stands as a weathered tribute to Arizona’s tumultuous frontier era when indigenous sovereignty clashed with America’s westward expansion.

You’ll find its significance deeply rooted in the struggle for control over the crucial Colorado River crossing, where Major Armistead’s troops protected settlers while subduing the Pipa Aha Macav (Mohave people) who’d farmed and traded there for generations.

After serving as a critical military strategy point during westward migration, the fort’s darker legacy emerged in 1890 when it transformed into a boarding school.

For nearly four decades, this institution became an instrument of cultural assimilation, stripping over 300 Native children annually of their languages and traditions—a painful chapter in the complex relationship between America’s expansion and indigenous rights.

Frequently Asked Questions

Did Any Notable Military Officers Serve at Fort Mohave?

Yes, Major Lewis A. Armistead and Lieutenant Colonel William Hoffman served at Fort Mohave, enriching its military history as notable figures who established American control in the western frontier.

Were There Civilian Settlements or Businesses Near the Fort?

Yes, you’d have found civilian life flourishing near Fort Mohave with trading posts, supply stores, and small villages supporting local commerce along travel routes and the Colorado River.

What Happened to Fort Mohave During the 1870-1880S Mining Boom?

Like a beacon in the wilderness, Fort Mohave transformed during the 1870-1880s. You’d witness its evolution into a bustling hub, experiencing mining impact through expanded supply chains and population growth supporting nearby gold discoveries.

Did Fort Mohave Experience Any Significant Natural Disasters?

You’ll find Fort Mohave’s history remarkably peaceful regarding disasters. It experienced minimal earthquake activity despite regional fault systems, while flood events were less severe than elsewhere in Mohave County.

What Recreational Activities Did Soldiers Engage in at Fort Mohave?

Like eagles soaring above desert constraints, you’d find freedom in water sports, hiking, horseback riding, fishing and card games. Your leisure time balanced military duties with these rejuvenating sports activities along the Colorado River.

References

- https://riverratsrealty.com/fort-mohave-history/

- https://www.arizonan.com/ghost-towns/fort-mohave/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fort_Mohave

- https://www.arizonahighways.com/article/arizona-ghost-towns

- http://genealogytrails.com/ariz/mohave/ghost-towns.html

- https://www.ghosttowns.com/states/az/fortmohave.html

- https://www.msavhcc.org/hidden-arizona-history

- https://www.hmdb.org/m.asp?m=274460

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mohave_War

- https://www.legendsofamerica.com/fort-mojave-arizona/