Fram emerged during the 1848 California Gold Rush, transforming from a simple panning site into a bustling town with nearly 250,000 residents by 1852. You’ll find remnants of wooden structures, including the restored Old Town Hall rescued in 1971. Unlike well-preserved ghost towns like Bodie, Fram lacks tourist infrastructure and interpretive signs. Weather, vandalism, and limited resources threaten what remains of this once-thriving mining community’s rich heritage.

Key Takeaways

- Fram transformed from a thriving Gold Rush boomtown with 250,000 residents into a ghost town following mining decline and environmental restrictions.

- The town features preserved structures including the Old Town Hall, rescued by a historical society in 1971.

- Mining families lived in basic wooden shacks and tents, with saloons serving as community centers for news and social gatherings.

- Located at 37°27′54″N 121°58′28″W in the Sierra Nevada, Fram’s landscape includes rocky outcrops and seasonal creeks that supported mining.

- Unlike better-known ghost towns, Fram lacks formal preservation, tourist infrastructure, or interpretive materials, relying on volunteer preservation efforts.

The Rise and Fall of Fram’s Mining Economy

As the California Gold Rush swept across the Sierra foothills in 1848, Fram emerged as one of many hopeful boomtowns built on the promise of golden fortunes.

You’d have witnessed miners initially using simple panning techniques before advancing to more sophisticated mining technology like sluice boxes and hydraulic operations.

The town’s prosperity exploded as California’s non-Indian population surged from 14,000 to nearly 250,000 in just four years.

Supply stores, banks, and roads sprang up virtually overnight, with entrepreneurs like Wells Fargo establishing financial services to support the frenzy.

Commercial infrastructure materialized rapidly as opportunistic merchants rushed to serve the gold-seeking masses.

The discovery at Bidwell’s Bar on July 4, 1848, marked a significant milestone that attracted prospectors to the region.

But economic cycles proved relentless.

By 1853, many miners had adopted hydraulic mining techniques that used high-pressure hoses to blast away hillsides.

As surface gold diminished, deeper extraction required capital beyond small miners’ reach.

Environmental damage from hydraulic mining brought legal restrictions, while competition from new gold fields accelerated Fram’s decline, transforming this once-thriving hub into today’s ghost town.

Daily Life in a California Boom Town

In Fram’s heyday, you’d find mining families huddled in wooden shacks and tents, enduring harsh winters and muddy springs as they sought their fortunes in the surrounding hills.

The town’s three saloons served as more than drinking establishments—they functioned as community centers where miners exchanged news, settled disputes, and occasionally engaged in brawls that required the sheriff’s intervention.

You could purchase almost anything at Fram’s general store, which formed part of a complex mercantile network connecting the isolated settlement to San Francisco’s wholesale markets through treacherous mountain supply routes.

Like most Gold Rush settlements, Fram saw very few miners achieve significant wealth, as large corporations eventually dominated the profitable extraction operations while individual prospectors struggled to survive.

Saturday night social gatherings featured communal dances and picnics that provided much-needed respite from the grueling work of extraction, similar to the community events held in California’s oil boom towns.

Pioneering Mining Families

Three distinct patterns shaped the lives of pioneering mining families in Fram’s heyday: collaborative ventures, kinship networks, and diversified survival strategies.

You’d find families like the Gibsons and Burtons forming mining partnerships that pooled resources and labor to work promising claims. These alliances often strengthened through strategic marriages that consolidated mining interests. The partnership between the Gibson brothers and Burtons in early 1892 demonstrated how these mining ventures formed, though their relationship would eventually deteriorate into violent conflict.

Your ancestors didn’t just mine—they survived through versatility. When gold yields fluctuated, pioneering families supplemented income with carpentry, farming, or running taverns. Following the model of entrepreneurs like Joel and Jacob Harlan, many mining families opened stores to supply miners with essential tools and provisions.

Women and children panned alongside men or managed domestic affairs essential to the operation’s success.

Many mining families eventually evolved into agriculture, like James John Morehead who began in the mines but built lasting prosperity through ranching near Chico, demonstrating how these resilient pioneers shaped California’s economic landscape beyond the gold rush.

Saloon Social Centers

Four walls of a Fram saloon contained more than just whiskey and card games—they housed the beating heart of the mining community.

You’d find these wooden structures serving as impromptu town halls, business offices, and entertainment venues all rolled into one.

After a grueling day in the mines, you could unwind at the long bar, exchange news about fresh strikes, or participate in social gatherings that defined Fram’s cultural identity.

Saloon entertainment ranged from traveling magicians to theatrical performances that transported you from dusty reality to momentary fantasy.

The saloons weren’t merely drinking establishments—they were where you’d forge friendships, seal business deals, celebrate payday, and occasionally witness disputes settled by the nearby sheriff.

These gathering spaces created community among strangers seeking fortune in California’s golden hills.

Much like the famous Bird Cage Theatre in other boom towns, Fram’s saloons hosted melodramas that provided essential cultural entertainment for the isolated mining population.

Similar to Lil’s Saloon in Calico Ghost Town, these establishments became historical landmarks that later attracted tourists interested in the authentic Old West experience.

Mercantile Exchange Networks

Woven through the fabric of Fram’s daily existence, the mercantile exchange networks formed the commercial lifeline that sustained the remote mining settlement.

You’d find the general store stocked with goods that traveled thousands of miles—canned foods from the East Coast, fabrics from Europe, and mining tools from Eastern manufacturers.

Local merchant networks extended beyond cash transactions, as storekeepers acted as unofficial bankers, extending credit until your next payday or ore shipment.

During lean times, local barter flourished—your freshly mined gold dust might buy hardware, while a rancher’s beef secured flour and coffee. Like many towns established during the mass migration of early settlers, Fram’s economy adapted to the harsh realities of frontier life.

The mercantile wasn’t just a store but a community nexus where you’d gather for news from “back East” and participate in the economic web that determined Fram’s survival through boom and bust. Similarly to Calico Ghost Town, visitors today can explore these preserved general stores that once served as the heart of mining communities.

Notable Buildings and Landmarks That Remain

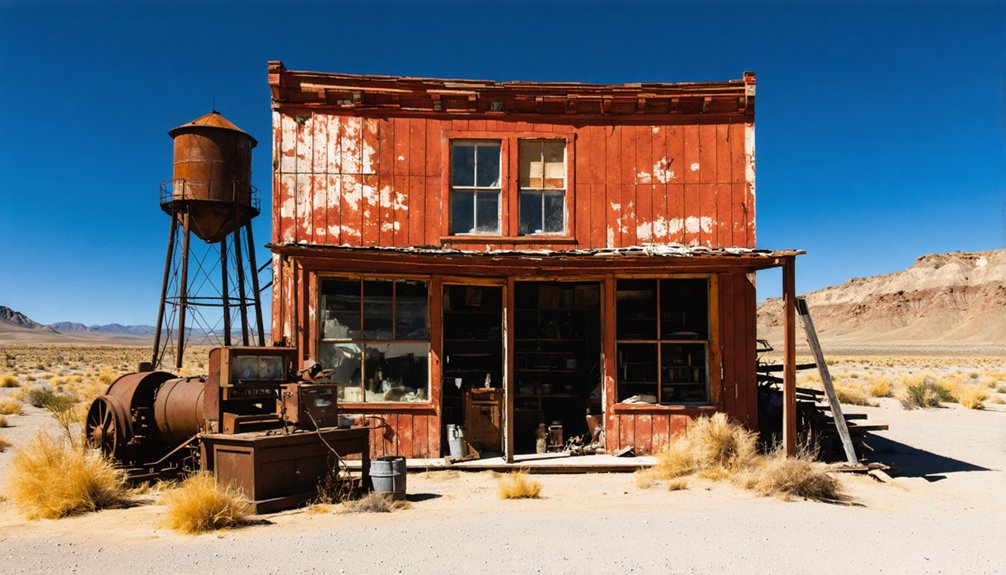

When you visit Fram today, you’ll find the partially restored Mining Company Headquarters with its distinctive Western facade and weathered signage still visible from the main dirt road.

The Old Town Hall stands as perhaps the most complete structure remaining, its foundation stones and partial walls outlining where community meetings and miners’ union gatherings once occurred.

These architectural remnants, alongside interpretive markers placed by the California Historical Society, offer glimpses into the administrative and civic heart that once governed this bustling mining community.

Mining Company Headquarters

Unlike many mining settlements that preserved their corporate infrastructure, Fram lacks any surviving mining company headquarters buildings today.

The Pacific Coast Borax Company, which operated extensively in the area, maintained its primary headquarters in San Francisco, with regional offices in Alameda housed in a pioneering reinforced concrete building designed by Ernest L. Ransome.

While you won’t find corporate offices in Fram itself, the nearby Harmony Borax Works once served as a processing center with company offices.

Administrative control of mining operations extended from Death Valley Junction, where railroad offices managed the essential transportation networks.

The true centers of power lay in these larger towns, leaving Fram as merely an operational outpost.

For a glimpse of preserved company history, visit the Borax Museum in Death Valley National Park.

Old Town Hall

Standing proudly as a tribute to Fram’s civic past, the Old Town Hall represents one of the few remaining architectural landmarks in this California ghost town. Built in the late 19th century, this multi-story brick structure once buzzed with civic engagement as the City Board of Trustees convened in the south room on the second floor.

You’ll appreciate how this versatile building served numerous functions beyond governance—housing a fire engine, newspaper offices, lawyers, and even shops for watch repair and barbering.

After falling into disuse, the historical society rescued this architectural gem in 1971, preserving its legacy alongside other important structures like the brick church that survived the 1934 fire.

The Old Town Hall’s restoration efforts maintain the authentic character that once defined Fram’s thriving community spirit.

Geographical Features and Natural Surroundings

Nestled within the rugged terrain of California’s eastern Sierra Nevada slopes, Fram occupies a distinctive geographical position at approximately 37°27′54″N 121°58′28″W.

The topographical features surrounding this forgotten settlement reveal a harsh yet beautiful landscape of rocky outcrops and arid soil that once challenged the resilience of its inhabitants.

Standing defiant against time, the rugged landscape bears silent witness to humanity’s brief tenacity against nature’s enduring power.

You’ll find evidence of the town’s lifeblood in its hydrological resources—seasonal creeks and springs that sustained both mining operations and daily life.

These waterways, now often reduced to dry beds except during winter rains, once dictated the rhythms of frontier existence.

The semi-arid climate has preserved many wooden structures while simultaneously wearing away others through relentless wind erosion.

Nature has reclaimed Fram, with drought-resistant chaparral slowly enveloping the remnants of human ambition.

Comparing Fram to Other California Ghost Towns

While Fram’s natural surroundings tell one story of California’s mining past, the town’s place in the broader tapestry of the state’s ghost towns reveals another dimension altogether.

Unlike Calico, which boasts extensive documentation and Walter Knott’s 1951 theme-park restoration, or Bodie with its $35 million gold production and 10,000 residents, Fram exists in historical obscurity.

You won’t find Fram preserved as a state park like Bodie’s “frozen in time” landscape, nor will you discover the tourist infrastructure of Calico.

In any ghost town comparison, Fram stands apart for its lack of recorded economic statistics or preservation efforts.

While Forest City maintains a handful of residents with modern amenities and Ballarat preserved stone structures for explorers, Fram represents California’s underdocumented mining ventures – towns that boomed, busted, and faded from collective memory.

Photographic Evidence and Historical Records

The photographic record of Fram tells a scattered, incomplete story through faded images and fragmented documentation. You’ll find no extensive photographic archives dedicated solely to this forgotten settlement—just weathered snapshots from the early to mid-20th century showing wooden structures surrendering to time.

These visual fragments reveal environmental reclamation in progress as desert vegetation slowly reclaims what humans abandoned.

While county and state archives house mining claims, property deeds, and census records, piecing together Fram’s timeline requires detective work. USGS maps chart the town’s physical evolution, while newspaper mentions and mining company documents illuminate its economic rise and fall.

Unlike Bodie or Calico, Fram lacks formal preservation efforts, making these historical records increasingly precious as physical evidence continues to disappear beneath the encroaching wilderness.

Modern Visitation and Tourism Opportunities

Unlike its photographic remnants, Fram’s status as a tourist destination tells an even sparser story.

You won’t find the well-marked trails or interpretive signs common at popular California ghost towns like Bodie or Calico. Fram exists in obscurity, lacking the documented accessibility routes, parking areas, or visitor amenities that draw crowds to more commercialized historical sites.

Fram stands defiantly ungentrified, a ghost town that refuses the interpretive plaques and tourist trappings of its more famous counterparts.

Ghost town accessibility here presents a stark contrast to destinations where tourism thrives.

No guided tours, events, or dedicated facilities appear in modern records. Visitor engagement opportunities remain virtually nonexistent—no self-guided tour maps, no information kiosks, no preserved structures marketed for exploration.

While adventure seekers might value Fram’s authentic abandonment, prepare for a true ghost town experience: undeveloped, undocumented, and untouched by modern tourism infrastructure.

Preservation Challenges and Future Outlook

Despite its obscure status, Fram faces preservation challenges similar to California’s better-known ghost towns, balancing between natural deterioration and limited protection measures. The town’s remote location compounds these issues, making consistent preservation strategies difficult to implement without dedicated funding and advocacy.

Three critical challenges for Fram’s future:

- Environmental threats from harsh weather and climate change accelerate structural decay, particularly affecting wooden buildings exposed to seasonal extremes.

- Limited resource allocation compared to more prominent sites like Bodie, requiring innovative community engagement and volunteer partnerships.

- Need for legal protections similar to the Bodie Protection Act to prevent potential mining interests or vandalism from threatening remaining structures.

You’ll find preservation efforts increasingly dependent on local historians and small volunteer groups who champion these forgotten pieces of California’s frontier heritage.

Frequently Asked Questions

Were Any Famous Outlaws or Celebrities Associated With Fram?

You won’t find famous outlaws or celebrity sightings connected to Fram. Historical records reveal no notorious criminals or Hollywood stars ever graced this forgotten settlement’s dusty streets or saloons.

What Indigenous Tribes Inhabited the Area Before Fram Was Established?

Before European contact, 85-90% of California’s indigenous population was decimated. You’d recognize the North Fork Mono, Yokuts, and Miwok as primary inhabitants, with tribal history reflecting their cultural significance across valley and foothill territories.

Did Fram Experience Any Major Disasters or Epidemics?

You won’t find records of natural disasters or disease outbreaks in Fram’s dusty history. The town’s decline came gradually through economic hardship, not sudden catastrophes that plagued other frontier settlements.

Are There Any Local Legends or Ghost Stories About Fram?

Unlike 45% of California ghost towns, Fram has no documented ghost sightings or haunted locations. You won’t find supernatural tales here—the town’s silent ruins speak only of forgotten mining dreams and desert isolation.

What Happened to the Cemetery and Burial Grounds?

You’ll find no cemetery restoration efforts have transpired; Purisima’s burial grounds remain largely untouched since 1868, quietly persisting where they’ve always been, while many graves have surrendered to time’s passage.

References

- https://www.camp-california.com/california-ghost-towns/

- https://www.sfgate.com/travel/article/calico-ghost-town-knotts-berry-farm-17643437.php

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4WEiOhY4jbQ

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ElbXVNDurPc

- https://californiacrossings.com/best-ghost-towns-in-california/

- https://capitolmuseum.ca.gov/state-symbols/silver-rush-ghost-town-calico/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_ghost_towns_in_California

- https://www.parks.ca.gov/?page_id=1081

- https://goldfieldsbooks.com/2021/02/02/gold-on-the-feather-river-a-timeline/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/California_gold_rush