Freeman Junction was established in 1873 by Freeman Raymond as an essential stagecoach stop in California’s Mojave Desert. You’ll find this ghost town at 3,192 feet elevation, where it once served miners and pioneers traveling between Los Angeles and mining camps. After surviving bandit threats and a violent 1909 uprising, it evolved into a gas station before being abandoned by 1978. Today, nothing remains of this California Historical Landmark except desert sands and forgotten stories.

Key Takeaways

- Freeman Junction began as an 1873 stagecoach stop in the Mojave Desert, established by Freeman S. Raymond at the crossroads of vital mining routes.

- The site was designated California Historical Landmark No. 766 in 1961, preserving its significance in western transportation history.

- Clare C. Miley revitalized the abandoned junction in the 1920s with a stone cabin that became a gas station, repair shop and restaurant.

- A violent 1909 Native American uprising resulted in several deaths and the burning of the stagecoach station.

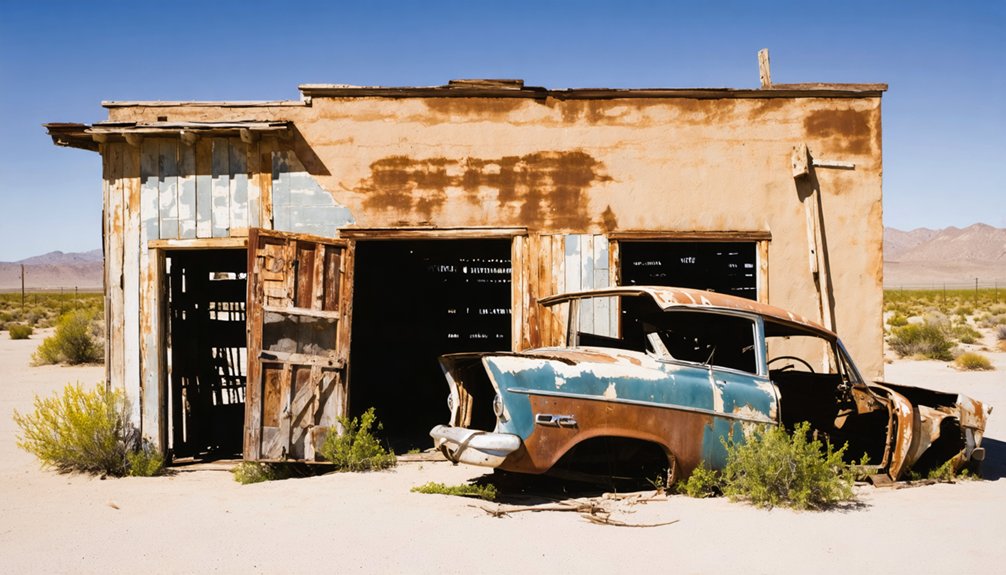

- The town was completely abandoned by 1978, with no physical structures remaining today as the desert has reclaimed the site.

The Stagecoach Stop: Freeman S. Raymond’s Frontier Outpost

As the harsh Mojave Desert winds whipped across the barren landscape in 1873, Freeman S. Raymond established his legendary stagecoach stop at a critical junction of desert trails. A former stage driver himself, Raymond knew exactly what weary travelers needed after grueling journeys through the Mojave.

You’d have found Freeman’s hospitality legendary among miners, freighters, and adventurers traversing between Los Angeles and distant mining camps. His strategic location near Walker Pass transformed this remote spot into a crucial frontier outpost where you could rest, resupply, and gather intelligence about conditions ahead.

Raymond’s desert oasis offered more than respite—it provided crucial knowledge for survival in the Mojave’s merciless expanse.

The station quickly became more than just a stopover—it evolved into a post office and community hub. This frontier station exemplified the transportation improvements that were crucial to western expansion during this period. Raymond and his family operated this vital station despite constant threats from bandits and hostile Native Americans in the area.

Raymond’s expertise in desert logistics saved countless lives, as his knowledge of water sources and safe passages proved essential in this unforgiving terrain.

Crossroads of Native American Trails and Pioneer Routes

Standing at Freeman Junction today, you’re treading upon ancient Native American pathways that once formed an essential desert crossroads long before Joseph Walker’s 1834 expedition established the significant mountain passage nearby.

As you scan the horizon toward Walker Pass, imagine the weary Death Valley ’49ers who reached this very spot in the winter of 1849-1850, making life-altering decisions about whether to continue west toward gold country or south to Los Angeles.

These converging trails beneath your feet tell silent stories of indigenous travelers, pioneering explorers, gold-seeking migrants, and the bandits who later exploited this strategic junction’s importance as a transportation lifeline. The notorious bandit Tiburcio Vasquez was known to target travelers passing through this vital intersection. This historic location was officially recognized as a state landmark on November 3, 1961, preserving its significance in California’s transportation history.

Ancient Pathways Converge

Long before Freeman Junction became a waypoint on maps of the American West, it served as a vital crossroads where ancient footpaths carved by Native American travelers converged in the harsh Mojave Desert.

As you stand at this historic junction, you’re treading the same ancient trails that the Kawaiisu people navigated during seasonal hunting journeys.

These pathways weren’t merely routes through difficult terrain—they were lifelines of cultural exchange that connected inland desert peoples with coastal communities.

When Joseph Walker passed through in 1834, he merely discovered what indigenous peoples had known for centuries.

The junction’s strategic position at the base of Walker Pass made it invaluable—where decisions to head west toward fertile valleys or south toward Los Angeles would determine a traveler’s fate in this unforgiving land.

Walker’s Historic Passage

When Joseph R. Walker first traced this essential mountain corridor in 1834, he wasn’t discovering something new—he was following Indigenous routes that had existed for centuries.

At 5,250 feet elevation, Walker Pass created a natural gateway between worlds, connecting the fertile San Joaquin Valley with the vast Mojave Desert.

You’re standing at a crossroads of history where Tubatulabal guides once led pioneers through this strategic passage.

By 1843, the first wagon trains rumbled through, with Walker himself leading settlers westward. This lower-elevation alternative to other Sierra Nevada crossings proved critical for Gold Rush migrants seeking California’s promise.

John C. Fremont, who led a military surveying expedition through the pass in 1845, suggested naming it after Joseph Walker.

The pass remains virtually unchanged today—a monument to freedom’s pathway. The Pacific Crest Trail intersects at Walker Pass, providing hikers a popular campsite in this historic corridor.

As a National Historic Landmark, it preserves the convergence of Native wisdom and pioneer determination that shaped the American West.

Gold Rush Junction Point

Freeman Junction emerged as the beating heart of a complex trail network, where ancient Indigenous pathways and pioneer ambitions converged beneath the desert sky.

Here, at this significant crossroads, Native American trade routes predated Joseph Walker’s 1834 passage, laying groundwork for the westward expansion that would transform California.

During the Gold Rush, you’d have witnessed exhausted 49ers arriving from Death Valley in 1849-50, making life-altering decisions at this junction—north to gold fields or south toward Los Angeles.

The site’s strategic position connecting the Mojave Desert to the Sierra Nevada made it an essential waypoint for prospectors and pioneers alike.

Later, Freeman Raymond’s stagecoach station established the junction as a critical hub on Historic Trails linking desert mines with coastal settlements, cementing its place in California’s pioneering legacy.

Life at 3,200 Feet: Geography and Climate of the Junction

Nestled between the Sierra Nevada and Mojave Desert at 3,192 feet above sea level, Freeman Junction occupies a distinctive ecological niche that shaped its historical development and challenges. The elevation effects created a harsh yet manageable environment where you’d experience both scorching days and near-freezing nights as seasons shifted. The area requires active user participation during navigation through the changing weather patterns, much like modern security systems.

Where desert meets mountain, Freeman Junction’s extreme elevation crafts a world of temperature extremes and ecological resilience.

- You’d find sparse rainfall—less than 5 inches annually—forcing adaptation to persistent water scarcity.

- Spring winds would whip across the valley, stirring dust through converging desert trails.

- Creosote bush and Joshua trees dot the landscape, survivors in sandy, rocky soil.

- Wildlife remains limited to hardy desert species—reptiles and rodents thriving where others couldn’t.

- Climate challenges meant summer temperatures regularly exceeded 90°F, testing human endurance at this strategic crossroads.

This historic area is documented on the Freeman Junction topo map, which provides detailed elevation markers and terrain features for explorers of the ghost town.

The Violent Uprising of 1909: Conflict and Aftermath

When you visit the remains of Freeman Junction today, you’re treading on ground where Native Americans once fought to protect their ancestral homelands against what they viewed as invasion by homesteaders like the Raymond family, who were killed during the 1909 uprising.

The stagecoach station’s burning marked not just the destruction of physical infrastructure but raised profound questions about territorial justice in an era when indigenous rights were routinely ignored.

Walking these grounds invites reflection on competing claims to land and livelihood—with Native defenders seeing themselves as protectors of their heritage while settlers envisioned opportunity and progress in the same contested space. Freeman Raymond was known for his exceptional hospitality to travelers crossing the harsh Mojave Desert landscape. This conflict echoes the earlier advocacy of Bartolomé de las Casas, who spent decades campaigning against the mistreatment of indigenous peoples throughout the Americas.

Native Motivations Examined

Throughout the decades following American conquest, California’s Native peoples endured a systematic campaign of violence and displacement that laid the foundation for the explosive events of 1909.

When you explore the motivations behind this uprising, you’ll discover a complex web of Native grievances and Cultural resistance born from generations of suffering.

The principal factors driving Native participation included:

- Catastrophic population collapse from 150,000 to merely 30,000 in just two decades

- Forcible removal from ancestral lands to remote, barren territories

- State-sanctioned enslavement and disenfranchisement through discriminatory legislation

- Continued settler encroachment on remaining Native territories

- Complete absence of legal recourse or protection under American law

This desperate resistance represented a rare collective stand against the machinery of dispossession, when surviving communities finally reached their breaking point.

Raymond Family Fate

The violent uprising of 1909 sealed the Raymond family’s fate in a single blood-soaked night that forever altered Freeman Junction’s trajectory. The attack claimed several homesteaders’ lives as flames consumed the stagecoach station that had stood as a symbol of Freeman Raymond’s desert legacy.

You won’t find any traces of the Raymond family in the settlement’s later history. Their pioneering spirit and hospitality, once the backbone of this desert outpost, vanished with the smoke that rose from their burning home.

For years afterward, the junction lay abandoned, a silent reflection of shattered dreams and family survival cut short. The violence represented more than personal tragedy—it embodied the complex tensions between settlers and Native peoples fighting for their traditional ways in a rapidly changing American West.

Territorial Justice Questions

Justice remains an elusive concept when examining the 1909 uprising at Freeman Junction, with territorial rights and cultural perspectives clouding any simple moral judgment. The conflict represents the complex intersection of indigenous rights and Euro-American expansion that defined America’s frontier era.

When considering territorial justice questions, remember:

- Indigenous peoples defended lands inhabited for generations before homesteaders arrived

- No formal treaties or agreements documented the transfer of this specific territory

- Raymond’s homestead represented both progress and invasion, depending on perspective

- Violence became the final arbiter when legal systems failed both sides

- History’s silence on Native American participants denies them voice in their own story

You’re witnessing a forgotten chapter where America’s westward expansion collided with ancient territorial claims—each side believing justice favored their cause.

Notorious Bandits and Dangerous Passages Through Walker Pass

While traveling through the windswept corridors of Walker Pass today, you’d never guess it was once among California’s most treacherous routes, where notorious bandits like Tiburcio Vásquez and Joaquín Murrieta transformed the natural challenges of the Sierra Nevada into perfect ambush points.

These narrow canyons and rocky outcrops that slow your vehicle once slowed stagecoaches to a crawl, making them vulnerable to the likes of Vásquez and his gang. The bandit legends live on in tales of the February 1874 robbery at Coyote Holes Station, where shots rang out and travelers were captured.

The passage dangers weren’t limited to outlaws—extreme weather and treacherous terrain compounded travelers’ woes.

Murrieta’s rumored treasure caches remain hidden somewhere in these hills, a tantalizing reminder of the lawless freedom these bandits briefly claimed.

The Miley Era: Resurrection of a Ghost Town in the 1920s

After decades of dust and silence had reclaimed the ruins of Freeman Junction, a young homesteader named Clare C. Miley breathed new life into this forgotten crossroads in the 1920s.

Born in 1900, Miley and his wife established themselves where violence and flames had once erased earlier settlement attempts.

Miley’s legacy of ghost town resilience is evident in how he transformed this barren junction:

- Built a stone cabin that became their initial homestead

- Converted the cabin into a gas station and repair shop by the 1930s

- Added a restaurant serving weary desert travelers

- Pursued small-scale mining operations nearby

- Attempted to establish postal service in 1953

You can still sense the determined spirit that drove this brief renaissance before abandonment claimed Freeman Junction again in 1978.

From Gas Station to Ghost Town: The Final Years of Habitation

As the harsh desert winds carved time’s passage across the Mojave landscape during the 1930s, Clare Miley’s humble stone cabin underwent a significant transformation that would define Freeman Junction‘s final chapter.

The cabin became a gas station with car repairs, later expanding to include a restaurant at the junction of Routes 178 and 14.

You’d have found miners and travelers stopping at this small commercial hub, though the nearby mining operations held questionable economic viability.

By the 1950s, population decline had taken hold—the promised post office never materialized, forcing residents to journey to Inyokern for mail service.

The final residents departed by 1978, though official records marked the town’s emptiness by 1973.

Nothing remains today—the desert reclaimed Freeman Junction as passing travelers carried away the last physical reminders.

What Remains Today: California Historical Landmark No. 766

The desert landscape that once hummed with the activity of travelers, miners, and bandits now stands silent at Freeman Junction—its physical structures erased by time and human hands.

On November 3, 1961, California recognized the site’s historical significance by designating it as Historical Landmark No. 766.

- You’ll find no ghost town buildings—all dismantled or reclaimed by the desert

- The landmark commemorates where Joseph Walker crossed Indian trails in 1834

- Death Valley ’49ers split at this junction while escaping toward gold country

- Bandit Tiburcio Vásquez once preyed on stages and freight wagons here

- The original marker (now missing) was placed through preservation efforts by California State Park Commission and historical societies

Today, highways and the Los Angeles Aqueduct cross where Freeman Raymond’s stage station once stood—a crossroads that silently holds the memory of California’s pioneer past.

Freeman Junction’s Place in Mojave Desert Mining History

Nestled at the crossroads of ancient pathways and modern ambitions, Freeman Junction carved out a crucial role in the Mojave Desert’s mining saga during the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

At the intersection of history and progress, Freeman Junction became the beating heart of Mojave’s mineral wealth.

You’ll find its significance embedded in transportation logistics that connected lucrative mining districts like Bodie and Panamint Range to Los Angeles markets.

The Freeman Mining District itself boasted impressive operations, with 17 claims producing ore valued up to $120 per ton.

Mining innovations like the Blackhawk Mine’s 10-stamp amalgamation mill represented the era’s technological advancement.

While gold dominated extraction efforts, the surrounding region yielded a treasure trove of minerals—silver, copper, tin, and tungsten.

Freeman Junction’s strategic position made it indispensable to the desert’s diverse mining economy until resource depletion eventually silenced its bustling activity.

The Two Histories: Indigenous Heritage and Western Settlement

Beyond Freeman Junction’s mining legacy lies a more ancient chronicle, woven through centuries before prospectors ever arrived.

When you stand at this crossroads, you’re witnessing the convergence of two distinct historical narratives of profound historical significance:

- Native American trails once formed a vibrant network here, evidenced by bedrock mortars near the original spring

- Walker’s 1834 arrival marked the beginning of cultural exchange and conflict that would transform the region

- During 1849-50, Death Valley 49ers made critical decisions at this junction, accelerating indigenous displacement

- Freeman Raymond’s stagecoach station established Western infrastructure where ancient pathways once dominated

- Bandit Tiburcio Vásquez exploited the junction’s isolation, adding a layer of outlaw mystique to its already complex story

You’re walking ground where two worlds collided, forever changing the Mojave landscape.

Frequently Asked Questions

Did Any Famous People Visit Freeman Junction?

You’d find famous visitors traversing Freeman Junction: explorer Joseph Walker, bandit Tiburcio Vásquez, founder Freeman Raymond, and countless Gold Rush pioneers seeking freedom—all adding to its historical significance.

What Wildlife and Plants Are Native to Freeman Junction?

You’ll find creosote bush, Joshua trees, and desert sage dominating Freeman Junction’s landscape. Native species like desert tortoises and kit foxes roam freely, reminding us why habitat conservation remains essential to this wild terrain.

Were There Any Schools or Churches in Freeman Junction?

100% of historical records show no signs of churches or schools. You won’t find any church history or education legacy in Freeman Junction—it remained purely a transit stop, never developing community institutions.

What Caused the Final Abandonment in the 1970S?

You witnessed the final exodus when economic decline strangled the last businesses while transportation changes rerouted travelers away from your once-vital junction, leaving nothing but desert winds by 1978.

Are There Any Annual Events Commemorating Freeman Junction’s History?

Sadly, zero annual events commemorate Freeman Junction. While many California ghost towns host historical reenactments and community festivals preserving pioneer legacies, Freeman Junction’s complete abandonment left it without structures or local champions to celebrate its past.

References

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Freeman_Junction

- https://digital-desert.com/freeman-junction/

- https://tripbucket.com/dreams/dream/visit-freeman-junction-california/

- https://www.ghosttowns.com/states/ca/freemanjunction.html

- https://www.californiahistoricallandmarks.com/landmarks/chl-766

- https://kids.kiddle.co/Freeman_Junction

- https://evendo.com/locations/california/southern-california/landmark/freeman-junction-california-historical-landmark-no-766

- https://www.the-old-west.com/topics/article/what-is-the-american-frontier/

- https://npshistory.com/publications/poex/hrs.pdf

- https://desertgazette.com/blog/tag/freemans-station/