You’ll find several ghost towns accessible from the Appalachian Trail, including Rausch Gap’s mining foundations directly on the trail and Lost Cove near the Nolichucky River, abandoned in 1957 after serving as a moonshining stronghold. Elkmont preserves 19 historic structures from an elite 1900s resort community, while Kaymoor features wooden stairs leading to moss-covered iron mining ruins from the 1960s. These scattered remnants showcase rich Appalachian heritage as nature reclaims once-thriving settlements throughout the wilderness.

Key Takeaways

- Rausch Gap sits directly on the Appalachian Trail, featuring accessible mining town foundations for hikers to explore.

- Kaymoor offers wooden stairs leading to moss-covered iron ruins from mining operations that ended in the 1960s.

- Lost Cove’s last family left in 1957, leaving behind remnants of a notorious moonshining community near Nolichucky River.

- Blue Heron provides train access from Stearns, Kentucky, with a 6.5-mile exploration loop through the abandoned settlement.

- Elkmont preserves 19 historic buildings from an elite 1900s retreat, representing one of Appalachia’s most significant resort communities.

Abandoned Communities Hidden in Appalachian Wilderness

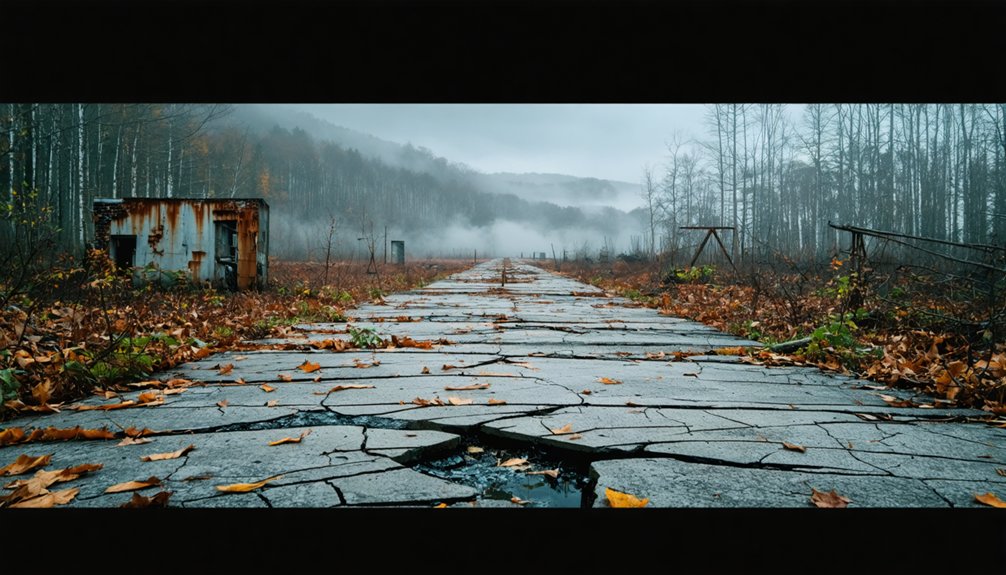

While modern hikers traverse well-marked sections of the Appalachian Trail, they’re often unaware that scattered throughout the surrounding wilderness lie the remnants of once-thriving communities that time and progress have left behind.

You’ll discover abandoned structures like Kaymoor’s wooden stairs descending to moss-covered iron ruins, where mining operations ceased in the 1960s.

Lost Cove’s agricultural settlement, notorious for moonshining since 1898, saw its last family depart in 1957. The area now fronts on the Nolichucky River, designated as a Significant National Heritage Area that attracts recreational activities.

Deep in Appalachian hollows, illegal distilleries once flourished where families carved out hardscrabble lives until mountain isolation finally claimed victory.

No Business, Tennessee offers stone ruins accessible only to determined explorers willing to venture off established paths.

These forgotten places reward wilderness exploration with tangible connections to Appalachian history, where nature has reclaimed what industry and isolation once claimed from the mountains. The coal mining legacy shaped these communities through decades of prosperity before economic shifts led to their inevitable abandonment.

Elkmont: From Exclusive Resort to Preserved Ruins

You’ll discover Elkmont’s transformation from an exclusive early 1900s retreat where Knoxville’s elite escaped to private cottages and the grand Wonderland Hotel.

The Appalachian Club, formed around 1910, created a gated community atmosphere that attracted influential conservationists like Colonel David Chapman, who ironically later supported the area’s incorporation into Great Smoky Mountains National Park.

When the National Park Service acquired these properties in the 1930s, lifetime lease agreements allowed original owners to remain until the 1990s, leaving behind approximately 60-70 historic structures that now represent one of Appalachia’s most significant preserved resort communities. The National Park Service now plans to preserve 19 buildings by 2025, following a historic preservation plan that halted earlier demolition efforts. Today, visitors can explore these ruins through internal links that connect to detailed information about each preserved building and its historical significance.

Appalachian Club’s Elite Legacy

When Knoxville’s hunting and fishing enthusiasts established the Appalachian Club in 1907, they couldn’t have imagined their exclusive mountain retreat would evolve into one of East Tennessee’s most prestigious social destinations.

The Little River Lumber Company’s 50-acre land grant in 1910 enabled clubhouse construction, while a 40,000-acre hunting lease transformed this sportsmen’s group into an elite socialization hub. The club added a hotel annex for social functions, further cementing its status as a premier destination.

You’d witness the Appalachian legacy through:

- Affluent members managing game and fish on Little River headwaters

- Exclusive cottages dotting the landscape near Daisy Town

- Business and civic leaders escaping to mountain sanctuaries

- Rejected applicants forming the rival Wonderland Club in 1919

These private enclaves represented freedom from urban constraints, where East Tennessee’s wealthy could retreat into wilderness luxury unavailable to common citizens. The nearby Wonderland Hotel had opened its doors just seven years earlier in 1912, adding another layer of luxury accommodation to the exclusive mountain community.

National Park Preservation Efforts

The Appalachian Club’s exclusive reign ended abruptly when Congress authorized the Great Smoky Mountains National Park on May 22, 1926, setting in motion a decades-long battle between wilderness preservation and private ownership.

You’ll discover that lifetime leases granted in the 1930s converted to 20-year terms in 1952, finally expiring in 1992. Approximately 70 structures sat abandoned, deteriorating rapidly until public outcry sparked action.

The 2009 compromise saved 19 buildings from demolition through historic preservation efforts. You can witness restoration techniques that returned structures to their original condition without modern modifications, matching authentic paint and materials. The Chapman-Byers Cabin served as the final restoration completed in this ambitious preservation project.

Friends of the Smokies established a $9 million endowment in 2020, completing full restoration by 2024. Today, you’ll explore these preserved ruins alongside wayside exhibits documenting Elkmont’s transformation. The site offers a unique atmosphere where preserved village meets reclaimed forest, creating an experience unlike any other location in the Smokies.

Lost Cove: Moonshine Capital of the State Lines

Nestled deep within the Nolichucky Gorge between Tennessee and North Carolina, Lost Cove earned its reputation as one of Appalachia’s most notorious moonshining strongholds during the early 1900s.

Hidden between state lines in the rugged Nolichucky Gorge, Lost Cove became Appalachia’s legendary moonshine capital during Prohibition era.

You’ll discover this remote settlement’s moonshine legacy began as early as 1898, when its strategic location on contested state lines created a jurisdictional nightmare for law enforcement.

The community’s isolation provided perfect cover for illegal operations:

- Unclear state boundaries prevented cross-border pursuit until the 1900s

- Bulk tank containers loaded moonshine directly onto passing trains during Prohibition

- Law enforcement actively avoided the disputed territory

- Remote location in Pisgah National Forest offered natural concealment

The town’s fortunes changed dramatically when the railroad arrived and a proper wagon road was constructed in 1912, bringing new economic opportunities beyond illicit distilling. The multiple uses of the Lost Cove name reflect its complex history across different regions and contexts.

Today, ghostly whispers of this defiant past echo through moss-covered ruins, where moonshining once provided primary income alongside timber in this barter society.

Thurmond: West Virginia’s Coal Boom Ghost Town

Along the banks of West Virginia’s New River, Thurmond rose from a single surveyor’s payment into one of America’s most legendary coal boom towns.

Captain William Thurmond’s 1873 land survey transformed 73 acres into a thriving railroad hub when the Chesapeake & Ohio Railroad bridged New River in 1888-1889.

Thurmond history reveals extraordinary prosperity during the 1920s peak, when more coal passed through this depot than Cincinnati, Ohio.

Eighteen train lines served the sole refueling stop across 73 miles of track, supporting coal mining operations throughout the region’s first two decades of the 1900s.

You’ll find stark contrasts defined this community.

While Captain Thurmond banned liquor, the notorious Dun Glen Hotel across the river offered jazz, gambling, and prostitution.

Today, you can explore this preserved ghost town within New River Gorge National Park.

Matildaville: Washington’s Failed Canal Vision

You’ll find the ruins of Matildaville near Great Falls, where George Washington’s ambitious vision to connect the Potomac and Ohio rivers through canal transport took physical form in 1785.

The town served as headquarters for the Patowmack Company’s canal operations, housing workers who spent seventeen years constructing locks and waterways around the treacherous Great Falls rapids.

Washington’s Potomac Canal Plan

While traversing the rocky terrain near Great Falls, you’ll encounter the remnants of Matildaville, a ghost town born from George Washington’s ambitious vision to transform America’s economic landscape through inland navigation.

Washington’s Potomac canal plan embodied both commercial opportunity and political necessity. He envisioned canal engineering that would bypass treacherous rapids, connecting western territories to Atlantic markets through economic integration.

The Patowmack Company, chartered in 1785, aimed to transport crucial goods:

- Flour and corn from frontier mills

- Whiskey distilled in backcountry settlements

- Timber and iron ore from inland forests

- Furs and tobacco bound for export

This waterway would bind the fragile republic together, preventing western lands from aligning with foreign powers. Washington understood that economic ties create political loyalty—making his canal vision fundamental for national unity and westward expansion.

Commercial Hub Dreams

In 1790, “Light-Horse” Harry Lee christened his ambitious 40-acre townsite Matildaville, honoring his deceased first wife while betting everything on Washington’s canal dreams transforming the Potomac wilderness into America’s next commercial powerhouse.

You can still trace Lee’s vision among Great Falls’ rocky outcroppings, where he planned a bustling trade center linking Georgetown’s commerce to Cumberland’s distant markets. His industrial aspirations centered on harnessing the canal’s surplus water for manufacturing, positioning Matildaville as the strategic hub between Virginia and Maryland’s cooperative waterway venture.

Lee envisioned thriving businesses serving canal workers, merchants, and travelers maneuvering the Potomac’s treacherous rapids.

Instead, you’ll find archaeological fragments of a town that never fulfilled its promise, succumbing to commercial decline when railroad technology bypassed waterway transport entirely.

Abandonment and Decline

Despite Lee’s grand commercial vision, Matildaville’s decline began almost immediately after the Patowmack Canal’s completion around 1802.

Economic challenges plagued the venture from the start, as extreme Potomac River flows restricted canal navigation to just one or two months annually. This severely limited toll revenues while maintenance costs soared.

You can trace Matildaville’s downfall through these critical factors:

- Chronic financial insolvency from astronomical construction and upkeep expenses

- Technological obsolescence as newer canal projects like the C&O Canal emerged

- Failed industrial diversification leaving the town dependent on doomed navigation

- Labor shortages and operational burdens that drained company resources

Elko Tract: The Military Decoy That Vanished

East of Richmond, Virginia, the federal government seized roughly 2,300 acres of farmland in 1942, transforming pastoral countryside into one of World War II’s most elaborate military deceptions.

You’ll find Elko Tract‘s remains scattered across what’s now White Oak Technology Park, where the 936th Camouflage Battalion constructed dummy aircraft, fake runways, and mock streetscapes designed to fool enemy bombers targeting Richmond Army Air Base.

This military deception never saw combat—no raids materialized—but its infrastructure tells a compelling story.

You can still trace abandoned street grids and utility systems that Virginia installed for a proposed African-American hospital in the 1940s. When local opposition killed that project, the site’s historical significance grew through decades of neglect.

Today, urban legends about secret bunkers persist, overshadowing Elko Tract’s actual role in wartime camouflage operations.

Proctor: Beneath the Waters of Fontana Lake

When the Tennessee Valley Authority completed Fontana Dam in 1944, it didn’t just create the deepest lake in North Carolina—it erased an entire mountain community from the map.

Proctor history began in 1886 as a thriving logging town, but wartime aluminum production demands sealed its fate beneath Fontana Lake.

A century-old mountain town sacrificed for America’s war effort—aluminum factories demanded power, and Proctor paid the ultimate price.

Over 1,300 families lost their homes, severing generations of mountain heritage.

You’ll find remnants of this drowned community when lake levels drop:

- Submerged foundations of the Ritter Lumber Mill

- Ghostly outlines of Highway 288 beneath the water

- Scattered stone chimneys emerging from the depths

- Cemetery headstones cut off from grieving families

The government’s broken promise to rebuild access became the infamous “Road to Nowhere”—a seven-mile symbol of bureaucratic failure that finally received a $52 million settlement in 2018.

Trail Access Routes to Historic Settlement Remains

While most Appalachian ghost towns require bushwhacking through dense forest or traversing unmarked paths, several abandoned settlements offer direct trail access that’ll lead you straight to their historic remains.

Rausch Gap sits directly on the Appalachian Trail, where you’ll walk through foundations of Pennsylvania’s once-thriving mining town.

Blue Heron offers train access from Stearns, Kentucky, plus a 6.5-mile loop for extended trail exploration of mining structures.

Tennessee’s No Business demands effort near Big South Fork River, requiring solid boots for remote stone ruins.

Lost Cove in North Carolina restricts access to foot travel only via Lost Cove Trail.

Elkmont provides easiest access through Great Smoky Mountains National Park’s popular campground, where nineteen protected buildings showcase preserved historic remnants.

Preservation Efforts Within National Park Boundaries

As national parks expanded across Appalachian regions during the 20th century, federal agencies inherited dozens of abandoned settlements that required immediate preservation decisions.

The National Park Service developed varied approaches to historic preservation based on structural integrity and cultural significance.

Preservation decisions weigh both the physical condition of historic structures and their importance to Appalachian cultural storytelling.

You’ll encounter different preservation strategies throughout these protected lands:

- Complete restoration – Elkmont’s 19 buildings receive full rehabilitation as museum exhibits

- Replica construction – Blue Heron’s metal shells replace decayed originals while preserving community layout

- Selective maintenance – Daisy Town’s structurally sound homes remain while unsafe structures face demolition

- Archaeological documentation – Shenandoah’s 88 catalogued sites protect settlement remnants through professional oversight

These efforts balance historical authenticity with visitor safety, ensuring you can explore Appalachian heritage while respecting the natural landscape’s restoration.

Planning Your Ghost Town Exploration Journey

Where should you begin when mapping your route through Appalachia’s abandoned settlements? Start by contacting local historical societies for precise ghost town locations and identifying abandoned buildings or railroads as entry markers.

Your hiking preparation should include reviewing park regulations for sites like Elkmont within Great Smoky Mountains National Park boundaries. Pack appropriate gear for remote backcountry hikes to places like Proctor’s remnants, and equip yourself for steep descents to preserved structures at Kmore’s bottom sections.

Consider weather impacts on trails such as the 6.5-mile Blue Heron Loop, accessible by train from Stearns, Kentucky. Remote areas like Fontana Lake have limited infrastructure, so plan accordingly.

For ghost town exploration safety, travel in groups when venturing to isolated paths and Blue Heron’s outer limits.

Frequently Asked Questions

Are Overnight Camping Permits Required When Visiting Ghost Towns Along the Trail?

Yes, you’ll need overnight camping permits when visiting ghost towns along the trail. Standard camping regulations apply regardless of location, and the permit process remains mandatory for all backcountry stays.

Which Ghost Towns Have the Most Dangerous Wildlife or Terrain Hazards?

Which sites pose greatest risks? You’ll face severe wildlife encounters and terrain challenges at former mining settlements with unstable shafts, bear-habituated campsites, and tick-infested overgrowth around collapsed structures throughout Virginia’s abandoned coal towns.

Can Artifacts or Historical Items Be Legally Collected From These Sites?

No, you can’t legally collect artifacts from ghost towns on federal trail lands without permits. Historical preservation laws and strict legal regulations protect these sites, making unauthorized collection a federal crime with serious penalties.

What’s the Best Time of Year to Visit for Optimal Weather Conditions?

October’s absolutely perfect for ghost town exploration! You’ll escape summer’s brutal heat and spring’s unpredictable storms. These best months offer crisp temperatures and stable weather patterns, giving you maximum freedom to roam abandoned sites comfortably.

Are Any Ghost Towns Completely Off-Limits to Public Access Year-Round?

No ghost towns are completely off-limits year-round along the trail. While ghost town regulations and access restrictions exist through military areas like Fort Indiantown Gap, you’ll find alternative routes maintain public access.

References

- https://www.blueridgeoutdoors.com/go-outside/southern-ghost-towns/

- https://appalachian.org/lost-cove-ghost-town-in-the-national-forest/

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4oHlJFXbrCk

- https://www.thewanderingappalachian.com/post/the-underwater-towns-of-appalachia

- https://appalachianmemories.org/2025/10/16/the-lost-towns-of-appalachia-the-forgotten-mountain-communities/

- https://thetrek.co/appalachian-trail/ghost-stories-appalachian-trail/

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hJp9DgkCA6s

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=L4pA4tExydQ

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Elkmont

- https://roadtrippers.com/magazine/abandoned-ghost-town-smoky-mountains/