America’s most notorious outlaws sought refuge in strategic ghost towns like Hole-in-the-Wall, Wyoming, with its natural fortress defenses, and Robber’s Roost, Utah, where Butch Cassidy’s Wild Bunch hid for decades. Jerome, Arizona transformed from a copper boomtown into the “wickedest town in the West,” while Ingalls, Oklahoma Territory, openly welcomed the Doolin-Dalton Gang. These sanctuaries formed an underground railroad of hideouts along the 3,000-mile Outlaw Trail, their stories preserved in weathered ruins.

Key Takeaways

- Ingalls, Oklahoma Territory served as a strategic operations base for the Doolin Gang with the Ransom Saloon as their gathering spot.

- Wyoming’s Hole-in-the-Wall provided natural fortress-like protection with a single narrow trail that made lawmen’s raids nearly impossible.

- Jerome, Arizona transformed from a copper boomtown of 15,000 people to “the wickedest town in the West” with abandoned mines concealing outlaw activities.

- Robber’s Roost in southeastern Utah sheltered Butch Cassidy’s Wild Bunch for over three decades with strategic hiding spots still visible today.

- The Outlaw Trail stretched 3,000 miles from Canada to Mexico with hideouts positioned about 200 miles apart for fugitives.

Ingalls: The Saloon Town That Sheltered the Doolin-Dalton Gang

While many frontier towns gained notoriety for their lawlessness, few embraced outlaws as openly as Ingalls, Oklahoma Territory, in the early 1890s. Under Doolin leadership, the gang consolidated several outlaw factions after the Dalton Gang’s decimation in Coffeyville, Kansas in 1892, establishing Ingalls as their primary sanctuary.

You’d find these outlaws freely wandering the streets, purchasing ammunition and supplies while enjoying local entertainment. The Ingalls economy thrived on their free-spending habits—townspeople often overlooking criminal activities for financial gain.

Outlaws spent lavishly in Ingalls, where morality bowed to profit and criminal cash fueled the local economy.

Local businesses, particularly saloons, profited handsomely when gang members arrived with pockets full of robbery proceeds. The notorious Ransom Saloon became a favorite gathering place for the gang members, where they would often engage in poker games despite the threat of law enforcement.

The town served as more than mere refuge; it functioned as a strategic operations base where stolen horses were kept, enabling quick escapes when marshals approached—a practical arrangement that sustained their criminal enterprise across multiple states. This hideout was the site of the infamous Battle of Ingalls on September 1, 1893, which resulted in casualties among lawmen and town citizens alike.

The Impenetrable Fortress of Hole-in-the-Wall

You’ll find few natural fortresses as strategically advantageous as Wyoming’s Hole-in-the-Wall, where a diverse coalition of outlaw gangs maintained separate quarters while sharing the protection of the Red Wall and Big Horn Mountains.

The hideout’s geography created an early warning system that detected approaching lawmen through narrow, easily defended passes, making it impossible for authorities to launch successful raids during its five decades of operation.

Within this sanctuary, separate gangs including Butch Cassidy’s Wild Bunch and the Jesse James gang maintained their own cabins and corrals while following a cooperative code that prohibited inter-gang theft, creating a rotating headquarters system that supported criminal operations across the American West. The hideout was accessed through an eroded rock wall that gave the location its distinctive name. The infamous Pinkerton detectives made numerous failed attempts to infiltrate the hideout and apprehend the outlaws hiding there.

Natural Defense System

A natural fortress unlike any other in the American West, Hole-in-the-Wall offered outlaws an almost impregnable sanctuary within Wyoming’s imposing Great Red Wall cliffs.

You’d encounter its primary defense—a single narrow trail through the pass—providing the only eastern access to the hideout. These natural fortifications created a strategic choke point where defenders could easily repel approaching lawmen.

The geological marvel featured hidden pathways known only to gang members, while loose rock and rugged terrain impeded pursuers’ progress. The area provided shelter to Butch Cassidy’s gang during harsh Wyoming winters when they weren’t actively robbing banks and trains.

From the pass, sentries enjoyed commanding 360-degree views of the surrounding plains, detecting approaching threats long before they reached the hideout.

This remote location, at least a full day’s ride from civilization, further enhanced its defensive capabilities—no law enforcement ever successfully captured outlaws within this sanctuary during its five decades of operation. The hideout was one of many strategic stations along the Outlaw Trail, which stretched approximately 1,000 miles from Montana to Mexico.

Rotating Outlaw Headquarters

Unlike modern criminal enterprises with fixed headquarters, the Hole-in-the-Wall served as a rotating base of operations for multiple independent outlaw gangs throughout its five-decade history.

Historical records reveal a sophisticated system of outlaw cooperation, with Butch Cassidy’s Wild Bunch, the Logan brothers, and even Jesse James’s gang taking turns utilizing the remote sanctuary.

The hideout logistics followed strict protocols for maintaining peace among these otherwise competing factions.

- Allocated cabins for each gang’s exclusive use during occupation periods

- Communal livery stables where horses were maintained between operations

- Shared supply stores with strict prohibition against inter-gang theft

- Self-governing dispute resolution methods that prevented authority intervention

- Collaborative resource contribution system ensuring sustainable long-term refuge

The location’s narrow access trail made it nearly impossible for lawmen to approach undetected, giving outlaws ample time to escape or prepare defense.

The Great Red Wall of Wyoming provided natural protection for the outlaws, making the hideout one of the most secure locations in the Old West.

Jerome and Old Trail Town: From Boom to Outlaw Sanctuaries

You’ll discover the stark duality of Jerome, where copper-born prosperity quickly surrendered to vice when nearly 15,000 people crowded this Arizona boomtown by the 1920s.

The “Billion Dollar Copper Camp” cultivated a thriving underworld of brothels, gambling dens, and saloons where gunfights erupted frequently despite official incorporation and attempts at civic order.

Though mining operations ceased by 1953 and the population plummeted below 100 residents, Jerome’s crumbling structures and relocated jail building still whisper stories of its outlaw heritage to modern visitors. The town’s transformation from a collection of board and canvas shacks to a frame and brick community with civic buildings happened during the early 20th century as the United Verde became Arizona’s largest copper mine. The town earned its notorious reputation as the wickedest town in the West due to the rampant prostitution, gambling, and alcohol consumption that defined its rowdy atmosphere.

Western Wealth’s Dark Side

While mining towns throughout the American West represented industrial progress and economic opportunity, their dramatic boom-and-bust cycles often created perfect conditions for lawlessness and criminal refuge.

Jerome’s decline from a thriving copper boomtown to a near-abandoned settlement by the 1950s exemplifies this transformation. As mining operations ceased and populations dwindled, abandoned structures became ideal hideouts for those seeking to escape legal scrutiny.

- Crumbling brick buildings with forgotten cellars offered secluded shelter for outlaws evading capture.

- Vast networks of abandoned mine tunnels provided concealed passage and storage for illicit goods.

- Remote hillside location on Cleopatra Hill afforded strategic vantage points to monitor approaching lawmen.

- Multinational population of over 30 nationalities created anonymity where strangers wouldn’t be questioned.

- Post-mining ghost town emptiness guaranteed minimal witnesses to outlaw lifestyle activities.

Bordellos and Bullets

As Jerome’s mining boom transformed the mountain town into a bustling hive of activity, an intricate ecosystem of vice emerged to serve the largely male workforce. Bordellos flanked the entertainment district alongside gambling halls and saloons, creating a trifecta of indulgence that defined Jerome’s mining culture.

You’ll find evidence of this lawless era in the infamous sliding jail, which dramatically shifted downhill after mining explosions, landing an entire block from its original foundation. The bordello history reveals establishments staffed by women from diverse backgrounds, catering to miners seeking respite from dangerous work.

As the mines eventually faltered, Jerome’s population dwindled, but its maze-like streets and abandoned buildings offered perfect sanctuary for fugitives. The town’s remote location and diminished law enforcement transformed it from industrial center to outlaw haven.

Abandoned Yet Alive

Once a thriving copper boomtown nestled precariously on Arizona’s Cleopatra Hill, Jerome defied the typical mining community lifecycle by refusing complete abandonment after its economic collapse.

When the mines closed in 1953 and population plummeted from 15,000 to merely 50 residents, Jerome’s abandoned history seemed inevitable. Yet the Historical Society’s preservation efforts transformed this “Wickedest Town in the West” into a vibrant culture hub by the 1960s.

- Unstable ground literally shifted buildings 225 feet downslope in 1938

- Smelter fumes decimated vegetation, accelerating landslides

- Massive mining blasts using 200,000 pounds of explosives shook foundations

- Five devastating fires repeatedly destroyed wooden structures

- Artists and entrepreneurs repopulated Jerome, creating today’s thriving National Historic District

Jerome’s remarkable resurrection proves that even places with outlaw reputations can reinvent themselves while preserving their heritage.

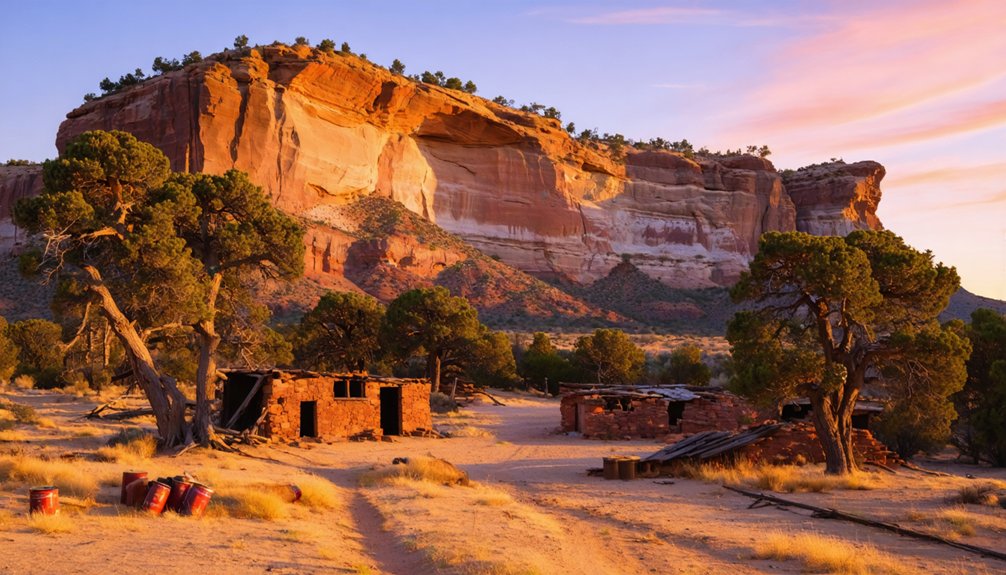

Robber’s Roost: Butch Cassidy’s Secret Stronghold

Nestled within the rugged wilderness of southeastern Utah, Robber’s Roost earned its reputation as one of the most impenetrable outlaw hideouts in the American West.

For over three decades, this labyrinth of steep-walled canyons between the Colorado, Green, and Dirty Devil Rivers concealed Butch Cassidy’s Wild Bunch from pursuing lawmen.

You’ll find remnants of their presence in stone fireplaces and the original corral still standing today—possible markers to hidden treasures.

The gang stocked provisions for months, using twenty-dollar gold pieces as poker chips during legendary encounters with fellow outlaws.

The Roost’s strategic location offered hundreds of hiding spots, while connections with local ranchers like the Bassett sisters guaranteed fresh supplies.

The Outlaw Trail: America’s Underground Railroad for Bandits

Stretching an impressive 3,000 miles from Fort MacLeod, Canada, to Mexico City, the Outlaw Trail served as a clandestine network that enabled America’s most notorious bandits to evade justice across multiple jurisdictions.

You’ll find this wasn’t simply a path but a sophisticated system of hideouts strategically positioned about 200 miles apart, allowing fugitives to rest between hard rides.

- Brown’s Hole where the Green River cuts through rugged terrain at the tri-state junction of Wyoming, Colorado, and Utah

- Hole-in-the-Wall’s natural fortress rising from Wyoming’s Big Horn Mountains

- Labyrinthine canyons of Robbers’ Roost providing perfect concealment in southeastern Utah

- Outlaw Tactics included “Pony Express” methods with horses stashed every 20 miles

- Trail Legends like Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid established this criminal infrastructure

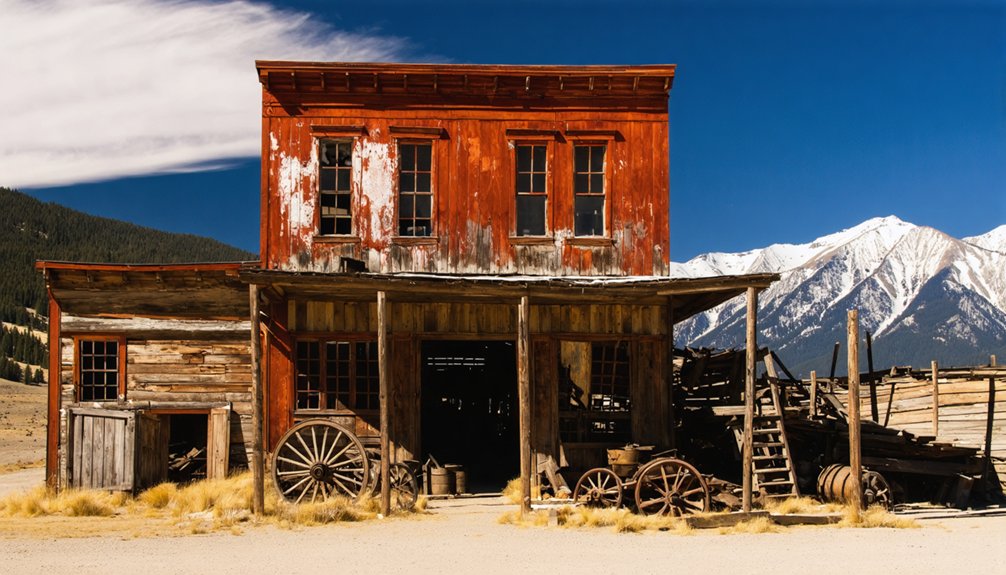

Preserved in Time: Ghost Towns That Tell Tales of Western Outlaws

While the Outlaw Trail provided the transportation network for America’s most notorious fugitives, the abandoned settlements they frequented offer an equally compelling window into criminal history.

Among these preserved relics, Wyoming’s Hole-in-the-Wall stands paramount. You’ll find this sanctuary nestled in the Big Horn Mountains, protected by towering red sandstone cliffs that once shielded Butch Cassidy’s Wild Bunch from law enforcement for nearly 50 years.

The architectural remnants—cabins, stables, and supply chambers—reveal sophisticated outlaw communities that operated without formal leadership structures.

As you explore these ghost towns, you’ll encounter outlaw legends that permeate every weathered plank and crumbling stone.

The Willow Creek Ranch, which now occupies the infamous hideout, contains hidden treasures for historians documenting America’s frontier criminal networks—archaeological evidence of a violent yet organized underworld that thrived beyond civilization’s reach.

Frequently Asked Questions

How Did Outlaws Communicate Between Hideouts Without Modern Technology?

With speed faster than a runaway stallion, you’d rely on trusted runners carrying secret codes, smoke signals across mountains, visual flags, hidden written messages, and exploitation of existing telegraph networks.

Did Any Women Play Significant Roles in These Outlaw Hideouts?

Yes, you’ll find female outlaws like Belle Starr and Laura Bullion were notorious accomplices who managed networks, gathered intelligence, and ran lucrative enterprises within these hideouts, fundamentally supporting outlaw operations.

What Happened to the Stolen Loot From These Notorious Gangs?

You’ll find most stolen treasures disappeared through spending, seizures by authorities, or remain as undiscovered hidden caches in remote locations. Historical records suggest gangs rarely maintained their ill-gotten wealth long-term.

How Did Local Residents Interact With Outlaws in These Communities?

You’d find complex community dynamics where residents welcomed outlaws for economic benefits, formed strategic alliances through social integration, or cooperated under coercion—all while balancing self-preservation against law enforcement pressures.

Were There Any Successful Law Enforcement Infiltrations of These Hideouts?

Despite what Google might tell you, you won’t find any successful infiltrations into these hideouts. Law enforcement tactics failed against Brown’s Hole, Robbers Roost, and the Outlaw Trail’s strategic impenetrability.

References

- https://www.visitstillwater.org/things-to-do/stillwater-area-history/the-doolin-dalton-gang-and-the-legacy-of-the-battle-of-ingalls/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hole-in-the-Wall_Gang

- https://www.cowboysindians.com/2024/10/halloween-hideaways-ghost-towns-of-the-west/

- https://capitolreefcountry.com/robbers-roost/

- https://www.wideopencountry.com/discover-the-outlaw-trail/

- https://www.christywanders.com/2024/08/top-ghost-towns-for-history-buffs.html

- https://www.thecollector.com/where-did-the-most-feared-gangs-of-the-wild-west-emerge/

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2sIM72082jc

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wild_Bunch

- https://biographics.org/the-doolin-dalton-gang-the-wild-bunch-of-the-wild-west/