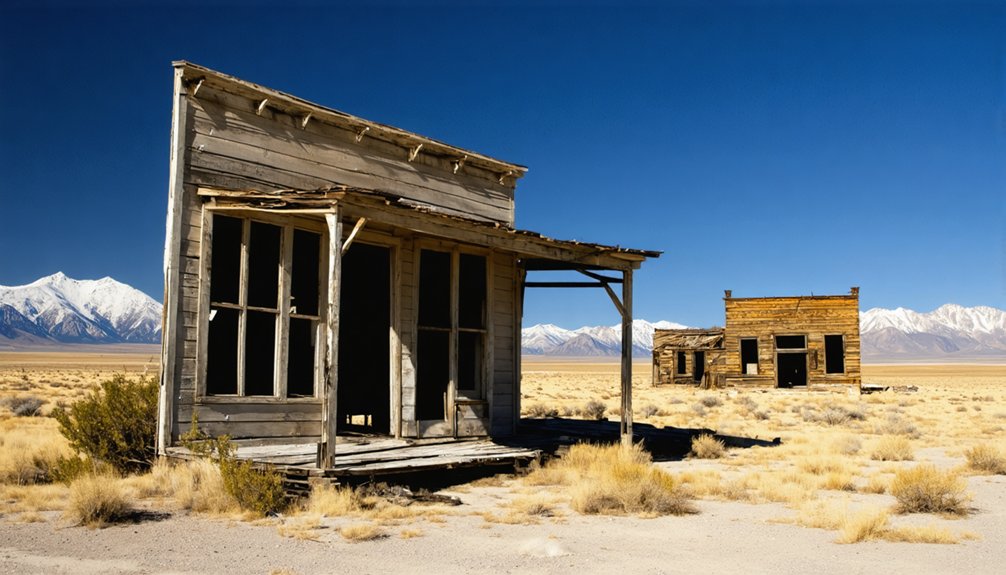

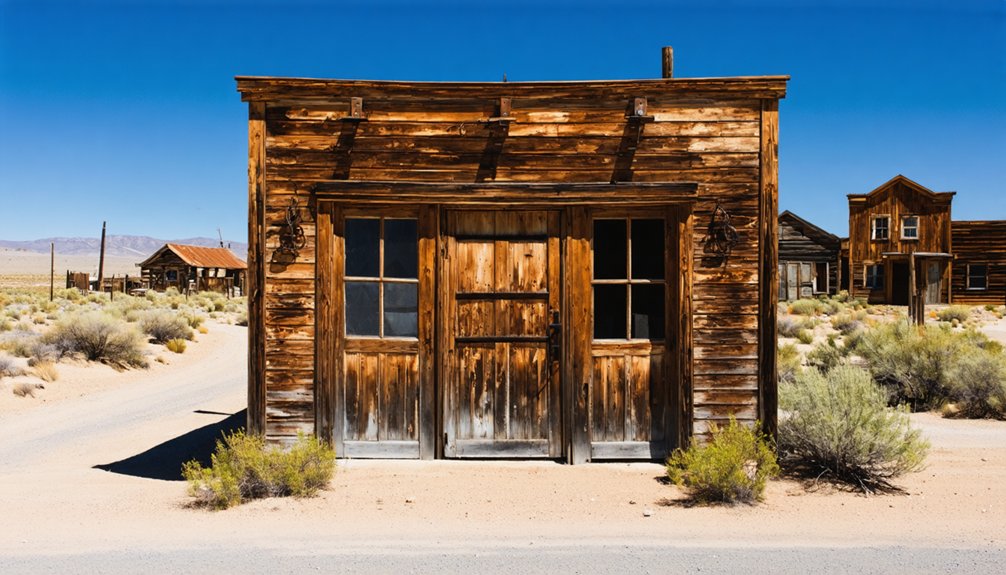

You’ll discover Eastern Oregon’s haunting ghost towns scattered across the high desert, from Shaniko’s massive wool warehouses that once stored 4 million pounds to Sumpter’s gold dredge that extracted $4 million in ore. Hardman’s population dwindled to 20 after the 1920s railroad bypassed it, while Greenhorn sits abandoned at 6,306 feet with zero permanent residents. Antelope survived a cult takeover in the 1980s, and Lonerock preserves its original 1880s jail and church—each settlement revealing distinct chapters of frontier boom-and-bust cycles that shaped the region’s remarkable history.

Key Takeaways

- Shaniko, once the “Wool Capital of the World,” declined after 1911 when rival railroads opened through Deschutes River Canyon.

- Sumpter’s gold mining economy peaked in the 1890s with over 2,000 residents before dredge operations ceased in 1954.

- Greenhorn, at 6,306 feet elevation, once housed 3,200 residents but now has zero permanent population after mining ended.

- Hardman’s population dropped to approximately 20 after railroad construction near Heppner shifted transportation economics in the 1920s.

- Antelope was temporarily renamed “Rajneesh, Oregon” in 1984 when cult followers outnumbered and outvoted local residents.

Shaniko: From Wool Capital to Whispers of the Past

In March 1900, when the Columbia Southern Railroad drove its final spike into the high desert plateau of north-central Oregon, businessmen from The Dalles set in motion one of the most dramatic boom-and-bust cycles in the state’s history.

Shaniko exploded into existence as a planned railroad terminus, and within three years the wool industry transformed this outpost into the self-proclaimed “Wool Capital of the World.”

You’ll find records showing five million dollars in wool sales during 1904 alone—staggering wealth for a settlement of 600 souls.

The Columbia Southern Railway constructed massive warehouses capable of storing 4 million pounds of wool, establishing the infrastructure for Shaniko’s dominance as a shipping center.

But railroad impact cuts both ways. When rival lines opened through Deschutes River Canyon in 1911, Shaniko’s lifeblood evaporated overnight.

A devastating fire destroyed much of the downtown business district, and lack of funds prevented the community from rebuilding what flames had consumed.

Today, just 36 residents guard the wind-swept remnants of Oregon’s fifth-largest Wasco County city.

Sumpter: Golden Dreams in the Elkhorn Mountains

When prospectors struck gold in the Blue Mountains’ Sumpter Valley in 1862, California Gold Rush veterans recognized terrain they’d seen before—mineral-rich streambeds carved through pine forests at 4,400 feet elevation.

By the 1890s, you’d find a booming town with seven hotels, sixteen saloons, and an opera house serving over 2,000 residents.

After surface gold depleted, dredge technology transformed the valley. Three massive machines worked continuously from 1935 to 1954, their bucket chains processing entire streambeds to extract $4 million in gold.

Yet operating costs exceeded returns, accumulating $100,000 debt by shutdown.

Today you’ll discover this mining heritage preserved at Sumpter Valley Dredge State Heritage Area, where weekend demonstrations teach traditional panning techniques. The 93-acre park attracts over 15,000 visitors annually, making it a premier destination for mining history enthusiasts.

The town’s population now hovers under 200, sustained by tourists exploring America’s most accessible gold dredge. Visitors can explore approximately 1.5 miles of trails winding through park wetlands and viewing platforms that showcase nature’s gradual reclamation of the valley.

Hardman: A Once-Thriving Hub Now Silent

At the turn of the century, you’d have found Hardman bustling with three general stores, two hotels, a newspaper office, meeting halls, and even a skating rink and racetrack serving the surrounding wheat fields and grazing lands.

The railroad’s arrival near Heppner in the 1920s shifted transportation economics away from this stagecoach hub, and the town that “lived hard and died fast” watched its post office close in 1968.

Today you’ll encounter roughly 20 residents among a couple dozen remaining structures, including an old lodge on the National Register, scattered across this 3,600-foot plateau 20 miles south of Heppner. The town wasn’t always called Hardman—it started with the memorable name Raw Dog before being renamed after postmaster David Hardman. Hardman actually emerged from the merger of two settlements, Raw Dog and Yellow Dog, creating this unique community.

Peak Era Prosperity

You’d have found three distinct commercial centers:

- Retail establishments – Three general stores stocking dry goods, two hotels hosting travelers, and a telephone office connecting isolated ranchers.

- Social amenities – Two meeting halls, skating rink, racetrack, and fraternal lodges (Masons, Knights of Pythias, Rebekahs, United Artisans).

- Industrial operations – Two sawmills struggling to meet lumber demand, blacksmith shops, saloons, and a newspaper documenting frontier progress.

The excellent public school convinced farmers to relocate families permanently, solidifying Hardman’s position as eastern Oregon’s premier rangeland community. Surrounding the town at 3,600 feet elevation, the fertile tableland produced wheat yields averaging twenty bushels per acre, with exceptional fields reaching fifty bushels. David N. Hardman brought a post office to town in 1881, with the community subsequently bearing his name.

Decline and Abandonment

Though Hardman’s prosperity seemed unshakeable during its peak years, the town’s fate was sealed when railroad construction near Heppner—20 miles north—bypassed the community in the 1920s.

You’d have witnessed transportation shifts that rendered the stagecoach stopping point obsolete overnight. Farm and grazing products now moved through new rail routes, draining Hardman’s economic lifeblood.

The economic decline followed swiftly. General stores, hotels, the newspaper, meeting halls, skating rink, and racetrack all faded by the early 1900s.

The post office—established in 1881 by David N. Hardman himself—hung on until 1968, but services dwindled year by year. The telephone office closed, commercial centers emptied, and buildings stood abandoned. The last business closed in 1968, marking the end of Hardman’s commercial era.

Eastern Oregon’s small towns faced this same pattern: when railroads chose different paths, communities simply vanished. Today, Hardman exists as a Class D ghost town, with only a small resident population remaining among the deteriorating structures.

Greenhorn: The Town That Vanished Completely

When you climb to 6,306 feet on the Baker-Grant county line, you’ll find Greenhorn—Oregon’s highest incorporated city with a permanent population of zero.

The town that once housed 3,200 residents during its 1890s peak now stands as a collection of weathered buildings accessible only by a six-mile seasonal road from Sumpter.

What began with gold strikes on Olive Creek in 1864 transformed into Robinsonville, then Greenhorn, before mines exhausted themselves and Federal Public Law 208 halted gold operations in 1942, sealing the town’s fate.

Gold Rush Beginnings

In 1864, prospectors struck gold on Olive Creek, and within a year the settlement of Robinsonville sprang up near what would become Greenhorn. The gold discovery triggered a rush of independent miners who established mining camps throughout the Blue Mountains, transforming the remote wilderness into a bustling frontier economy.

The region’s development followed a predictable pattern:

- Placer mining operations extracted surface gold from creek beds and hillsides.

- Lode mining expanded as prospectors discovered underground gold deposits.

- Population swelled to 3,200 residents by the 1890s during peak activity.

When Robinsonville burned in 1898, miners relocated and reorganized.

Complete Abandonment by 2010

By 1910, Greenhorn’s infrastructure reflected a town confident in its future—two hotels welcomed visitors, fire hydrants lined streets connected to a municipal waterworks system, and general stores stocked provisions for a seasonal population of 500 residents plus another 1,500 miners scattered across nearby camps.

Population trends shifted dramatically when mines petered out by the early 1920s, accelerating a decline that’d already claimed two-thirds of residents between 1900 and 1910.

Mining impacts became permanent when Federal Public Law 208 outlawed gold mining in 1942, severing the town’s economic lifeline. The post office closed in 1919, marking the beginning of the end.

Antelope: From Stagecoach Stop to Cult Controversy

The stagecoach route connecting The Dalles to Canyon City’s gold fields gave birth to Antelope in the 1870s, establishing what would become one of Eastern Oregon’s most resilient—and later infamous—settlements.

This stagecoach stop prospered through the 1920s with nearly 300 residents, surviving an 1898 fire that destroyed most structures at $70,000 in damages.

The town’s character changed dramatically when Rajneesh followers purchased the 64,000-acre Big Muddy Ranch in the early 1980s, triggering unprecedented cult controversy.

The peaceful stagecoach town transformed overnight when thousands of red-clad followers descended upon the high desert community.

The takeover unfolded rapidly:

- Over 7,000 devotees flooded the area, outnumbering locals

- Followers registered as voters, blocking disincorporation attempts in 1982

- The town name officially changed to “Rajneesh, Oregon” in September 1984

Following the 1984 bioterror attack that sickened 750 people, leaders fled.

Today, Antelope stands reclaimed but diminished, harboring just 37-46 independent souls.

Lonerock: Preserving Pioneer Heritage

Lonerock emerged from Eastern Oregon’s grasslands in the early 1870s when ranchers needed a service center for their sprawling operations. Settlers platted the town in 1882, naming it after the 35-foot rock that still marks the landscape.

You’ll find Edward Wineland’s 1874 sawmill launched construction that brought a school, post office, and Methodist church by 1898.

The 1896 fire destroyed the business district, while Highway 97’s 1917 route isolated the community. The Department of Defense’s mid-1950s actions pushed residents out.

Yet pioneer preservation efforts kept the original jail and church standing through decades of decline.

Today’s community revival started when new Gilliam County arrivals refused to let history fade. The well-maintained 1898 church and schoolhouse prove that determined locals can reclaim their heritage.

Exploring Eastern Oregon’s Abandoned Legacy

Eastern Oregon’s wool empire built Shaniko in 1900 when The Dalles bankers and businessmen designed it as a planned shipping hub.

You’ll find architectural remnants throughout this 30-person town—hotel, city hall, fire hall, and jail still stand despite Portland’s rail line redirecting commerce to Bend.

The cultural significance of these settlements reveals itself through preserved structures:

- Hardman’s decline began with an 1898 fire, then Highway 97’s bypass sealed its fate as a true ghost town.

- Sumpter’s massive gold dredge towers over Baker County, evidence of 2,000 residents who once operated three newspapers and an opera house.

- Greenhorn’s seven homes mark complete abandonment—population dropped from hundreds to zero by 2010.

Between Shaniko and Antelope, you’ll photograph Cross Hollow’s stage stop remnants, where stone walls outlasted the flames.

Frequently Asked Questions

What Is the Best Time of Year to Visit Ghost Towns in Eastern Oregon?

Visit during early fall for ideal seasonal weather—September offers fewer crowds, clear skies for photography tips like golden-hour shots, and accessible trails before snow closes high country routes you’ll want to explore independently.

Are Any of These Ghost Towns Private Property or Restricted Access?

Yes, you’ll find access restrictions at several sites. Private ownership affects locations like McDonald’s ranch buildings in Sherman County and parts of Hardman. You’re advised to check local conditions and respect property boundaries before exploring these historical areas.

What Safety Precautions Should Visitors Take When Exploring Abandoned Buildings?

You’ll need sturdy boots, gloves, and a dust mask when entering abandoned structures. Test floors before stepping, stay near walls, bring a partner, watch for rattlesnakes and other wildlife encounters, and always inform someone of your location.

Can You Camp Overnight Near These Ghost Towns?

You’ll find camping’s a mixed bag—some ghost towns like Cornucopia offer rustic lodging, while others require you to stay at nearby RV parks or primitive sites. Check local camping regulations since ghost town amenities vary wildly.

How Far Apart Are These Towns From Each Other for Trip Planning?

Ghost town distances range from 8 to 60 miles apart. You’ll find Antelope closest to Shaniko at 8 miles, while Lonerock sits farthest at 60 miles. Travel routes connect via Highway 207 and regional roads.

References

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_ghost_towns_in_Oregon

- https://thatoregonlife.com/2016/04/road-trip-ghost-towns-eastern-oregon/

- https://www.visitoregon.com/oregon-ghost-towns/

- https://eastoregonian.com/2019/04/11/ghosts-of-eastern-oregon/

- http://www.photographoregon.com/ghost-towns.html

- https://www.nationaldaycalendar.com/lists/12-oregon-ghost-towns

- https://www.pdxmonthly.com/travel-and-outdoors/2025/10/oregon-ghost-towns-history

- https://traveloregon.com/things-to-do/culture-history/ghost-towns/

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6gHFUM4MNck

- https://www.legendsofamerica.com/or-shaniko/